HIV and pregnancy

HIV in pregnancy is the presence of an HIV/AIDS infection in a woman while she is pregnant. There is a risk of HIV transmission from mother to child in three primary situations: pregnancy, childbirth, and while breastfeeding. This topic is important because the risk of viral transmission can be significantly reduced with appropriate medical intervention, and without treatment HIV/AIDS can cause significant illness and death in both the mother and child. This is exemplified by data from The Centers for Disease Control (CDC): In the United States and Puerto Rico between the years of 2014–2017, where prenatal care is generally accessible, there were 10,257 infants in the United States and Puerto Rico who were exposed to a maternal HIV infection in utero who did not become infected and 244 exposed infants who did become infected.[1]

The burden of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, including mother-to-child transmission of HIV, disproportionately affects low- and middle-income countries, in particular the countries of Southern Africa.[2] The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 1.3 million women and girls living with HIV become pregnant each year.[3]

The risks of both neonatal HIV infection and maternal illness are reduced by appropriate prenatal screening, treatment of the HIV infection with antiretroviral therapy (ART), and adherence to recommendations after birth. Notably, without antiretroviral medications, obstetrical interventions, and breastfeeding recommendations, there is approximately a 30% risk of mother-to-child HIV transmission.[4] This risk is reduced to less than 1% when the previously mentioned interventions are employed.[5] The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) therefore recommends HIV testing as a routine component of both pre-pregnancy and first trimester prenatal care to ensure expedient and appropriate interventions.[6]

HIV infection is not a contraindication to pregnancy. Women with HIV may choose to become pregnant if they so desire, however, they are encouraged to talk with their doctors beforehand. Notably, 20-34% of women in the United States living with HIV are unaware of their diagnosis until they become pregnant and undergo prenatal screening.[7]

Mechanism of transmission

HIV can be transmitted from an infected mother to the neonate in three circumstances: across the placenta during pregnancy (in utero), at birth due to fetal contact with infected maternal genital secretions and blood, or postnatally through the breast milk.[8] This type of viral transmission is also known of as vertical transmission. It is thought that mother-to-child HIV transmission most commonly occurs at the time of delivery when the baby comes into direct contact with the mother's infected blood or genital secretions/fluid in the birth canal.[8] Maternal treatment with ART therapy prior to delivery decreases the viral load, or the amount of virus present in the mother's blood and other body fluids, which significantly reduces the chance of viral transmission to the fetus during labor.[8]

Signs or symptoms

Maternal

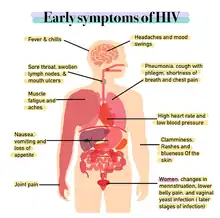

HIV infections in adults typically follow a 3-stage course, as described below:

- Early, acute stage

- The early stage of an HIV infection involves rapid viral replication and infection.[9] This stage typically lasts for 2–4 weeks following an infection and subsequently resolves spontaneously. Between 50 and 90% of adults experience symptoms during this phase of infection.[8][10][11] At this time, women can experience fever, sore throat, lethargy, swollen lymph nodes, diarrhea, and a rash. The rash is described as maculopapular, which means it is composed of flat and raised skin lesions, and it appears on the trunk, arms and legs but does not appear on the palms of the hands or sole of the feet.[8]

- Middle, chronic/latent stage

- The middle stage of an HIV infection can last for 7–10 years in a patient who is not being treated with ART therapy.[8] During this time, the virus itself is not latent or inactive, but it is sequestered inside of the lymph nodes, where it is replicating at low levels.[9] Women are generally asymptomatic during this period but some can experience persistent fevers, fatigue, weight loss, and swollen lymph nodes, which is known as the AIDS-related complex (ARC).[8]

- Late, advanced/immunodeficient stage

- AIDS is caused by the progressive destruction of CD4 T-helper cells of the immune system by the HIV virus. AIDS is defined by either a CD4 cell count of less than 200 cells per microliter (which is indicative of severe immunodeficiency), or the development of an AIDS-specific condition.[9] Because they are immunocompromised, women in this stage are at risk for serious, opportunistic infections that the general population either does not contract or contracts very mildly. These types of infections cause significant illness and death in patients with HIV/AIDS.[1] People with such advanced HIV infections are also at greater risk for developing neurological symptoms (for example dementia and neuropathy), and certain cancers (for example Non-Hodgkin's B-Cell Lymphoma, Kaposi's Sarcoma, and HPV-associated cancers including anal, cervical, oral, pharyngeal, penile and vulvar cancer).[8]

Infant

The clinical presentation of HIV in untreated infants is less predictable and specific than that of an adult infection. Notably, if an HIV diagnosis is diagnosed and appropriately treated, symptoms and complications in the infant are rare. Without ART therapy, infants born with HIV have a poor prognosis. If symptoms develop, the most common include persistent fevers, generalized lymph node swelling, enlarged spleen and/or liver, growth failure, and diarrhea. These children can also develop opportunistic infections, notably including recurrent oral thrush (Candidiasis) and/or Candida diaper rash, pneumonia, or invasive bacterial, viral, parasitic, or fungal infections. Neurologic symptoms, particularly HIV encephalopathy, are common in infants with untreated HIV.[11]

Diagnosis/screening

Pregnancy planning

The main factors to consider in pregnancy planning for HIV positive individuals are the risk of disease transmission between the sexual partners themselves and the risk of disease transmission to the fetus. Both risks can be mitigated with appropriate perinatal planning and preventative care.[12]

ACOG and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) recommends all couples in which one or both partners are HIV positive seek pre-pregnancy counseling and consult experts in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Infectious Disease, and possibly reproductive endocrinology and infertility to ensure couples are getting appropriate, individualized guidance based on their specific disease states and weighing the risks to the fetus associated with taking ART medications.[13][14]

Couples in which only one partner is HIV positive are at risk of transmitting HIV to the uninfected partner. These couples are known as serodiscordant couples. The CDC reports that HIV positive people who are able to sustain undetectable viral loads while taking ART therapy have a negligible risk of transmitting HIV to their partner through sex based on observational data from multiple large scale studies, most notably the HPTN052 clinical trial, the PARTNER study, the PARTNER2 study, and the Opposites Attract Study.[15] The NIH therefore advises that HIV positive people who maintain an undetectable viral load via adherence to long-term ART therapy can attempt conception via condomless sex with minimal risk of disease transmission to the HIV negative partner.[14] The NIH further recommends that aligning condomless sex with peak fertility, which occurs at ovulation, via ovulation test kits and consultation with clinical experts can maximize the chance for conception.[14]

When the HIV positive individual in a serodiscordant partnership has not achieved viral suppression or his or her viral status is unknown, there are other options for preventing transmission amongst partners. The first option includes administering Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis ART Therapy (PrEP) to the HIV negative partner, which involves once daily dosing of a combination drug to prevent the transmission of HIV following condomless sex.[14] The NIH advises administering PrEP to serodiscordant couples who are going to attempt conception via condomless sex, however, they emphasize that adherence is absolutely necessary to effectively protect the HIV negative partner.[14] The other option for achieving conception while simultaneously preventing HIV transmission amongst partners is reproductive assistance. When the female attempting to conceive is HIV positive, she can undergo assisted insemination with semen from her partner to reduce the risk of transmission.[14] When the man in the partnership is HIV positive, the couple can choose to use donor sperm or utilize sperm preparation techniques (for example, sperm washing and subsequent viral testing of the sample) and intrauterine or in vitro fertilization to achieve conception to reduce the risk of transmission to his partner.[14]

In couples where the male and female are both HIV positive, conception may occur normally without concern for disease transmission amongst each other. However, it is vital for any HIV positive mother to initiate and maintain appropriate ART therapy under the guidance of an HIV expert prior to and throughout pregnancy to reduce the risk of perinatal transmission to the fetus.[14]

Although assisted reproductive techniques are available for serodiscordant couples, there are still limitations to achieving a successful pregnancy. women with HIV have been shown to have decreased fertility, which can affect the available reproductive options.[16] women with HIV are also more likely to be infected with other sexually transmitted diseases, placing them at higher risk for infertility. Males with HIV appear to have decreased semen volume and sperm motility, which decreases their fertility.[17] ART may also affect both male and female fertility and some drugs can be toxic to embryos.[18]

Testing in pregnancy

Early identification of maternal HIV infection and initiation of ART in pregnancy is vital in preventing viral transmission to the fetus and protecting maternal health, as HIV-infected women who do not receive testing are more likely to transmit the infection to their children.[6][19] The CDC, NIH, ACOG, and American Academy of Pediatrics each recommend first trimester HIV testing for all pregnant women as a part of routine prenatal care.[7][1] The NIH further elaborates on this recommendation, indicating that HIV testing should be conducted as early as possible wherever a woman seeks care and initially determines she is pregnant (for example, in the Emergency Department).[7] First trimester HIV testing is conducted simultaneously with other routine, early pregnancy lab work in the United States, including: a complete blood count, blood typing and Rhesus factor, urinalysis, urine culture, rubella titer, hepatitis B and C titers, sexually transmitted infection testing, and tuberculosis testing.[20] ACOG advises that prenatal caregivers repeat third trimester HIV testing prior to 36 weeks gestation for the following women: those who remain at high risk for contracting an HIV infection, those who reside in areas with a high incidence of HIV infection in pregnancy, those who are incarcerated, or those with symptoms suggestive of an acute HIV infection.[6] For women who have not received prenatal care or who have not been previously tested for HIV infection during pregnancy, ACOG and the NIH suggest performing rapid HIV screening in the labor and delivery unit prior to delivery or immediately postpartum.[6][7]

HIV testing in the United States is currently offered on an opt-out basis, per the CDC's recommendation.[19] Opt-out testing involves educating the patient on the impact of an HIV infection on pregnancy, notifying the patient that HIV screening is recommended for all pregnant women, and informing her that she will automatically receive the test with her other routine lab work unless she explicitly declines the test and signs a consent form to have it removed from her lab panel.[6] The alternative model, known as the opt-in model, involves counseling women on HIV testing, following which they elect to receive the test by signing a consent form. The opt-in model is not recommended by the CDC, as it is associated with lower testing rates.[7]

If a woman chooses to decline testing, she will not receive the test. However, she will continue to receive HIV counseling throughout pregnancy so that she may be as informed as possible about the disease and its potential impact. She will be offered HIV testing at all stages of her pregnancy in case she changes her mind.[21]

The most updated HIV testing protocols recommend using the HIV-1 and HIV-2 antigen/antibody combination immunoassay as the initial screening test for an HIV infection.[22] This blood test assesses whether or not the mother has created antibodies, which are disease-fighting proteins of the immune system, against the HIV-1 and HIV-2 viruses. These antibodies will only be present if the patient has been exposed to HIV, therefore, they act as a marker of infection. This test also detects a protein called p24 in maternal blood, which is a specific component of the HIV virus itself and also acts as an early marker of an HIV infection. If this test is positive, the CDC recommends performing follow-up testing using a test called the HIV-1/HIV-2 antibody differentiation immunoassay that both confirms the diagnosis and determines the specific type of HIV infection the patient has to specifically tailor further management of the patient.[22]

Sometimes, however, a person may be infected with HIV but the body has not produced enough antibodies to be detected by the test.[7] If a woman has risk factors for HIV infection or symptoms of an acute infection but tests negative on the initial screening test, she should be retested in 3 months to confirm that she does not have HIV, or she should receive further testing with an HIV RNA assay, which can be positive earlier than the antibody/antigen immunoassay.[7][23] Antiretroviral medications should be initiated at the time of maternal HIV diagnosis and they should be continued indefinitely.[24]

Treatment/management

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission

The risk of HIV transmission from mother to child is most directly related to the plasma viral load of the mother. Untreated mothers with a high (HIV RNA greater than 100,000 copies/mL) have a transmission risk of over 50%.[25] For women with a lower viral load (HIV RNA less than 1000 copies/mL), the risk of transmission is less than 1%.[26] In general, the lower the viral load, the lower the risk of transmission. For this reason, ART is recommended throughout the pregnancy so that viral load levels remain as low as possible and the risk of transmission is reduced.[7][27] The usage of ART drugs that effectively cross the placenta can also act as pre-exposure prophylaxis for the infant, as they can achieve adequate ART drug levels in the fetus to prevent acquisition of the viral illness.[27] Finally, it is recommended that ART drugs be administered to the infant following birth to continue to provide protection from the virus that the infant could have been exposed to during labor and delivery.[27][28]

.png.webp)

All pregnant women who test positive for HIV should begin and continue ART therapy regardless of CD4 counts or viral load to reduce the risk of viral transmission.[27] The earlier ART is initiated, the more likely the viral load will be suppressed by the time of delivery.[27][29] Some women are concerned about using ART early in the pregnancy, as babies are most susceptible to drug toxicities during the first trimester. However, delaying ART initiation may be less effective in reducing infection transmission.[30]

Antiretroviral therapy is most importantly used at the following times in pregnancy to reduce the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV:

- During pregnancy: pregnant women infected with HIV receive an oral regimen of at least three different anti-HIV medications.[31]

- During labor and delivery: pregnant women infected with HIV who are already on triple ART should continue with their oral regimen. If their viral load is high (HIV RNA greater than 1,000 copies/mL), or there is question about whether medications have been taken consistently, then intravenous zidovudine (AZT) is added at the time of delivery.[32] Pregnant women who have not been on ART prior to delivery or who have been on ART for less than four weeks should also be given intravenous AZT or a single dose of nevirapin (sdNVP), tenofovir (TDF) and emtricitabine (FTC) and a three-hourly dose of AZT.[33]

According to current recommendations by the WHO, CDC and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), all individuals with HIV should begin ART as soon as they are diagnosed with HIV. The recommendation is stronger in the following situations:[34]

- CD4 count below 350 cells/mm3

- High viral load (HIV RNA greater than 100,000 copies/mL)

- Progression of HIV to AIDS

- Development of HIV-related infections and illnesses

- Pregnancy

Labor and delivery

Women should continue taking their ART regimen on schedule and as prescribed throughout both the prenatal period and childbirth. The viral load helps determine which mode of delivery is safest for both the mother and the baby.[35]

According to the NIH, when the mother has been receiving ART and her viral load is low (HIV RNA less than 1000 copies/mL) at the time of delivery, the risk of viral transmission during childbirth is very low and a vaginal delivery may be performed. A cesarean delivery or induction of labor should only be performed in this patient population if they are medically necessary for non-HIV-related reasons.[35]

If the maternal viral load is high (HIV RNA greater than 1000 copies/mL) or if her HIV viral load is unknown around the time of delivery (more than 34 weeks gestation), it is appropriate to schedule a cesarean delivery at 38 weeks to reduce the risk of HIV transmission during childbirth. In these situations, this is the appropriate management guideline regardless of whether or not the mother has taken prenatal ART.[35]

Sometimes, women who have a high viral load who should receive a caesarean delivery will present to the hospital when their water breaks or they are in labor, and management for these patients is specific to each patient and will be determined at the time of presentation, as a cesarean delivery may not significantly reduce the risk of infection transmission.[35] The NIH recommends that healthcare providers in the United States contact the National Perinatal HIV/AIDS Clinical Consultation Center at 1-888-448-8765 for further recommendations in these situations.[35]

All women who present to the hospital in labor and their HIV status is unknown or they are at high risk of contracting an HIV infection but have not received repeat third trimester testing should be tested for HIV using a rapid HIV antigen/antibody test.[35] If the rapid screening is positive, intravenous (IV) zidovudine should be initiated in the mother immediately and further confirmatory testing should be performed.[35]

IV Zidovudine is an antiretroviral drug that should be administered to women at or near the time of delivery in the following situations:[35]

- High viral load (HIV RNA greater than 1000 copies/mL)

- Unknown viral load

- Clinical suspicion for maternal noncompliance with prenatal ART regimen

- Positive rapid HIV antigen/antibody test at labor or prior to a scheduled caesarean delivery

Administration of IV Zidovudine can be considered on a case-by-case basis for women who have a moderate viral load (HIV RNA greater than or equal to 50 copies/mL AND less than 1000 copies/mL) near the time of delivery. IV Zidovudine is only not administered if women are both compliant with their prescribed ART regimen throughout pregnancy and have maintained a low viral load near the time of delivery (HIV RNA less than 50 copies/mL between 34 and 36 weeks gestation).

Further considerations for managing HIV positive women during labor and delivery include the following recommendations to reduce the risk of HIV transmission:[35]

- Avoid fetal scalp electrodes for fetal monitoring, particularly if the maternal viral load is greater than 50 copies/mL.

- Avoid artificial rupture of membranes and operative vaginal delivery (using forceps or a vacuum extractor) if at all possible, particularly in women who have not achieved viral suppression. If these methods need to be employed, they should be conducted carefully and following obstetric standards.

- The potential interactions between the specific ART drugs taken by the mother and those administered during labor should be considered by healthcare providers prior to drug administration.

Immunizations

All pregnant women should receive the inactivated influenza vaccine and the TdaP vaccine, which covers tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (whooping cough) during the first trimester, regardless of their HIV status.[36] If a pregnant woman tests positive for HIV, she should also be administered the pneumococcal vaccine, meningococcal vaccine, and Hepatitis A vaccine and Hepatitis B vaccine following a conversation with her provider.[36] Vaccination is important to prevent serious infectious complications associated with the aforementioned diseases, which patients with HIV are at higher risk of contracting.[36]

Pregnant women should notably not receive live vaccines, including the Human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine, measles mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine, live influenza vaccine, and varicella (Chicken pox) vaccine regardless of their HIV statuses, as these vaccines can potentially harm the fetus.[37]

Further evaluation

The following monitoring tests are recommended for women who are diagnosed with HIV prior to or during pregnancy:[38]

- HIV Viral Load (via HIV RNA Levels) at the initial prenatal visit, 2–4 weeks after starting or changing ART, monthly until viral load is undetectable, at least every 3 months subsequently throughout pregnancy, and between 34 and 36 weeks to inform decisions regarding labor and delivery.

- CD4 Count at the initial prenatal visit. This lab should be repeated every 3 months for pregnant women have been on ART for less than 2 years, have inconsistent ART compliance, CD4 counts less than 300 cells per millimeter cubed, or a high viral load. Otherwise, CD4 count does not need to be monitored following the initial visit.

- HIV Drug Resistance Testing should be performed prior to initiating ART in any pregnant woman including those who have and have not taken antiretroviral medications before, and when modifying failing ART regimens for pregnant women. Note, ART should be initiated prior to receiving the results of drug resistance testing.[39]

- Standard Glucose Screening to monitor for gestational diabetes.

- Liver Function Tests within 2–4 weeks after initiating or changing ART drugs and every 3 months subsequently.[27]

- Monitoring for ART Toxicities based on the specific drugs that have been prescribed.

- Aneuploidy Screening should initially be offered via noninvasive methods. If these tests are abnormal or an abnormal ultrasound is performed, invasive testing via amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling can be performed once an ART has been initiated and the HIV viral load is undetectable.

- Hepatitis A, B, and C Screening should be performed in all pregnant women with HIV because coinfection is common.[40][27]

- Further Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI) Screening should be performed as HIV positive women are at a higher risk for co-infection than the general population, and exposure to other STIs is associated with stillbirth, preterm delivery, low birth weight, and other complications. Screening should include syphilis, gonococcal, chlamydial, and trichomonal infection.[27]

- Tuberculosis Testing as HIV positive patients are at high risk for developing active tuberculosis.[27]

- Testing for prior Toxoplasma Exposure should be performed in HIV infected pregnant women, as reactivation of Toxoplasma gondii infection can occur with a low CD4 count (less than 100 cells per microliter), and has the potential to cause congenital toxoplasmosis in the fetus, which has many associated birth complications.[27][41]

- Testing for Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Exposure should similarly be performed, as CMV is the most common congenital infection and is associated with congenital hearing loss, major handicaps, and death in exposed infants.[27][41]

Antiretroviral medications

The goals of antiretroviral administration during pregnancy are to reduce the risk of transmission of HIV from mother to child, to slow maternal disease progression, and to reduce the risks of maternal opportunistic infection and death. It is important to choose medications that are as safe as possible for the mother and the fetus, and are effective at decreasing the total viral load. Certain antiretroviral drugs carry a risk of toxicity for the fetus. However, the overall benefits of an effective ART regimen outweigh the risks and all women are encouraged to use ART for the duration of their pregnancy.[27][42] It is important to note that the associations between birth defects and antiretroviral drugs are confounded by several important factors that could also contribute to these complications, for example: exposure to folate antagonists, nutritional and folate status, and tobacco, alcohol, and drug use during pregnancy.[27]

The recommended ART regimen for HIV-positive pregnant women is similar to that of the general population. In the United States, the favored ART regimen is a three-drug routine in which the first two drugs are NRTIs and the third is either a protease inhibitor, an integrase inhibitor, or an NNRTI.[43]

- Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) are considered the "backbone" of ART and 2 of these medications are generally used in combination.

- Due to its known safety profile and extensive use in pregnant patients, zidovudine-lamivudine is the preferred choice as the NRTI backbone. Zidovudine may worsen anemia so anemic patients are advised to use an alternative agent.

- For women who are coinfected with hepatitis B, tenofovir with either emtricitabine or lamivudine is the preferred NRTI backbone.[43]

- NRTI use may cause a life-threatening complication called lactic acidosis in some women, so it is important to monitor patients for this problem. Deaths from lactic acidosis and liver failure have been primarily associated with two specific NRTIs, stavudine and didanosine. Therefore, combinations involving these drugs should be avoided in pregnancy.[31]

- Protease inhibitors (PIs) have been studied extensively in pregnancy and are therefore the preferred third drug in the regimen. Atazanavir-ritonavir and darunavir-ritonavir are two of the most common PIs used during pregnancy.

- There is conflicting data regarding the association between protease inhibitors with preterm births. Boosted lopinavir has the strongest correlation with this outcome, so women who are at a high risk for premature delivery are advised not to use this drug.[44]

- Some PIs have been associated with high blood sugar (hyperglycemia) but is unclear whether or not they contribute to the development of gestational diabetes.[31]

- Some PIs have been noted to cause hyperbilirubinemia and nausea, so these side effects should be monitored for closely.

- Integrase inhibitors (IIs) are generally the third drug in the regimen when a PI cannot be used. They rapidly reduce the viral load and for this reason, they are often used in women who are diagnosed with HIV late in their pregnancy. Raltegravir (RAL) is the most commonly used.[44]

- Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) may be used during pregnancy, however, there are significant toxicities associated with their use. NNRTIs are therefore them less desirable options for ART. The most commonly administered NNRTIs in pregnancy are efavirenz (EFV) and nevirapine (NVP).[44]

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

.jpg.webp)

Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) should be offered in the form of oral combination tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) to patients who are at risk of acquiring HIV and are trying to become pregnant, who are pregnant, who are postpartum/breastfeeding. People who are considered at risk for developing HIV are those who participate in condom-less sex with a partner who is HIV positive, patients who have been diagnosed with a recent sexually transmitted infection (STI), and patients who engage in injection drug use. PrEP is notably optional if a patient's HIV positive partner has been reliably on ART and has an undetectable viral load. PrEP can reduce the risk of both mother and fetal acquisition of HIV. Patients who take PrEP should be counseled on the importance of strict medication adherence and tested for HIV every three months and be aware of the symptoms of an acute HIV infection in case of viral contraction.[12]

Nutritional supplements

Vitamin A plays a role in the immune system and has been suggested as a low-cost intervention that could help with preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV. However, analysis of 5 large studies that utilized Vitamin A supplementation to prevent HIV transmission showed that said supplementation likely has little or no effect on transmission of the virus in pregnant women. Vitamin A supplementation has been largely superseded by antiretroviral therapy on a global basis.[45] Furthermore, high doses of natural Vitamin A can be toxic to the fetus, which is important to consider in management of HIV in pregnant women.[46]

Maternal follow-up

The most important component of maternal follow-up for HIV positive mothers in the postnatal period is ART. All mothers should continue their antiretroviral medications following hospital discharge, and any changes to their regimens should be made in consultation with the physicians who coordinate their HIV care. The NIH also advises that providers should be wary of the unique challenges to medication compliance that mothers face in the postpartum period when designing a discharge ART regimen for their patients.[47]

Infant Treatment and Follow-Up

All newborns who were exposed to HIV in utero should receive postpartum antiretroviral drugs within 6 hours of delivery, and their dosing should be based on the newborn's gestational age. Premature newborns should only receive zidovudine, lamivudine, and/or nevirapine based on toxicity testing.[48]

Newborns who were exposed to HIV in utero and whose mothers were on ART prior to and during pregnancy and achieved viral suppression by delivery should be administered zidovudine for 4 weeks to continue preventing HIV transmission following delivery. If a pregnant woman presents in labor with an unknown HIV status and a positive rapid HIV test result or an infant has a high risk of HIV transmission in utero (for example, the mother was not taking antiretroviral drugs in the pre-pregnancy period or during pregnancy, the mother had not achieved viral suppression, or the mother experienced an acute HIV infection during pregnancy or while breastfeeding), the infant should be started on a presumptive three drug ART regimen for treatment of the infection until the infant's test results are available. If the infant has a documented HIV infection after birth, they should be started on 3-drug ART at treatment doses that will be continued indefinitely.[48]

In infants younger than 18 months, HIV testing must consist of virologic assays that directly detect the HIV virus, not HIV antibody testing, as it is less reliable in the postpartum period. The results of these tests can be affected by antiretroviral drugs, so they should be repeated. All infants exposed to HIV in utero should be tested at three ages: 14–21 days, 1–2 months, and 4–6 months. Any positive HIV testing should be repeated as soon as possible. HIV cannot be excluded as a diagnosis in an HIV-exposed, non-breastfed infant until the infant has had either two or more negative virologic tests at at least 1 month and 4 months of age, or two negative HIV antibody tests at at least 6 months of age.[49]

Other important testing for newborns includes a complete blood count at birth to determine a baseline for the infant's blood cell numbers. The infant should then be followed with appropriate laboratory monitoring based on their gestational age and clinical condition, and both the fetal and maternal drug regimens. Important hematologic anomalies being monitored include anemia and neutropenia. If either of these complications occur, the infant may need to discontinue their ART regimen under physician supervision. Infants exposed to HIV in utero should also be receive preventative drugs against Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia between 4–6 weeks old after completing their 4-week course of antiretroviral medications, as this is a life-threatening complication of HIV.[50]

Although the risk is very low, HIV can also be transmitted to a baby through food that was previously chewed by a mother or caretaker infected with HIV. To be safe, babies should not be fed pre-chewed food.[50]

Breastfeeding

While maternal compliance with ART reduces the chance of HIV transmission to the infant, there is still a risk of viral transmission via the breastmilk. Furthermore, there is concern that maternal antiretroviral drugs can enter the breastmilk and cause toxicity issues in the infant or future drug resistance. For these reasons, the NIH, CDC, and the AAP each discourage breastfeeding amongst HIV-positive women in the United States and other developed nations because there are safe, affordable feeding alternatives and clean drinking water.[47][51][52] In fact, ACOG lists maternal HIV infection as one of very few contraindications to breastfeeding.[53]

Despite these recommendations, some women in developed countries chose to breastfeed. In these situations, it is important that mothers adhere strictly to their ART regimens and it is advised that infants are administered antiretroviral drugs for the prevention of possible viral transmission for at least 6 weeks. Notably, when mothers do not comply with their ART regimens, there is a 15-20% risk of infant HIV acquisition from breastfeeding over 2 years. Both infants and mothers should be regularly tested every throughout breastfeeding to ensure appropriate viral suppression and lack of HIV transmission. Maternal monitoring should be done with an assessment of HIV viral load, and infant testing should be done with virologic HIV testing.[54]

The WHO dictates that in developing nations, the decision about whether or not mothers breastfeed their infants must weigh the risk of preventing HIV acquisition in the infant against the increased risk of death from malnutrition, diarrhea, and serious non-HIV infection if the infant is not breastfed.[55] In developing nations, clean water and formula are not as readily available, therefore, breastfeeding is often encouraged to provide children with adequate food and nutrients because the benefit of nourishment outweighs the risk of HIV transmission.[56] The WHO's 2010 HIV and Infant Feeding Recommendations intend to increase the rate of HIV-survival and reduce non-HIV related risk in infants and mothers, and they include the following:[57]

- National health authorities in each country should recommend one, specific, universal infant feeding practice for mothers with HIV, as mothers will need persistent counselling while feeding their infants and this is better promoted when national authorities are unified in the guidance they administer. The choices for feeding include either breastfeeding while receiving antiretroviral medications or avoidance of all breastfeeding.

- When national health authorities chose the feeding practice they intend to promote and determine how to implement it, they should consider HIV prevalence, infant and child mortality rates due to non-HIV causes, current infant and young child feeding, the nutritional status of children, water quality, sanitation resources, and quality of health services.

- women who breastfeed while receiving ART should exclusively breastfeed their infants for 6 months and then continue breastfeeding for until the infant is 12 months of age. They used to be advised to discontinue breastfeeding at 6 months, however, this recommendation has been changed to improve long-term nutritional outcomes.

- Mixed feeding (when a baby is fed formula and breastmilk) should be avoided to reduce the risk of HIV transmission and avoid diarrhea and malnutrition.

In developing nations, If the mother has a high HIV viral load (HIV RNA more than 1000 copies/L), replacement feeding with formula is only initiated as per the UNAIDS guidelines, termed the AFASS criteria, "where replacement feeding is acceptable, feasible, affordable, sustainable, and safe."[58][33]:95-6 A mother should only give infant formula, as explained by the WHO, if the following conditions are met:[59]

- "Safe water and sanitation are assured at the household level and in the community; and

- the mother or other caregiver can reliably provide sufficient infant formula milk to support the normal growth and development of the infant; and

- the mother or caregiver can prepare it cleanly and frequently enough so that it is safe and carries a low risk of diarrhea and malnutrition; and

- the mother or caregiver can exclusively give infant formula milk in the first six months; and

- the family is supportive of this practice; and

- the mother or caregiver can access health care that offers comprehensive child health services."

Societal impacts

Discrimination

Despite advances made in preventing transmission, HIV-positive women still face discrimination regarding their reproductive choices.[60][61] In Asia, it was found that half the women living with HIV were advised not to have children and as many as 42% report being denied health services because of their HIV status.[62]

Compulsory sterilisation in an attempt to limit mother-to-child transmission has been practiced in Africa, Asia, and Latin American.[63][64][65] women are forced to undergo sterilisation without their knowledge or informed consent, and misinformation and incentives are often used in order to coerce them into accepting the procedure. The forced sterilisation of HIV-positive women is internationally recognized as a violation of human rights.[66]

Legal advocacy against this practice has occurred in some countries. In Namibia, litigation was brought against the government by three HIV-positive women who claimed they were coerced during labour into signing consent forms that gave permission for the hospital to perform a sterilisation.[67] The LM & Others v Government of Namibia case is the first of its kind in sub-Saharan African to deal with coerced sterilisation of HIV-positive women. The court ruled that these women were sterilised without their consent but failed to find that this was due to their HIV status.[68] A 2010 case in Chile have also aimed to seek government accountability for violation of sexual and reproductive rights of women living with HIV.[69]

Health considerations

Pregnant women with HIV may still receive the trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine and the tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccination during pregnancy.[70]

Many patients who are HIV positive also have other health conditions known as comorbidities. Hepatitis B, hepatitis C, tuberculosis and injection drug use are some of the most common comorbidities associated with HIV. women who screen positive for HIV should also be tested for these conditions so that they may be adequately treated or controlled during the pregnancy. The comorbidities may have serious adverse effects on the mother and child during pregnancy, so it is extremely important to identify them early during the pregnancy.[71]

Health disparities

There are well documented disparities with regards to who is affected by HIV/AIDS during pregnancy.[72][73] For example, a study of Florida births from 1998 to 2007 showed parents who were identified as Hispanic or Black in the medical records were more likely to have HIV during pregnancy.[73] Though more research is needed, poverty is a significant structural inequity that can drive these differences in HIV rates.[74][75][76] Furthermore, there are large disparities in access to antiretroviral therapies, medications important in preventing the transmission of HIV from parent to child.[77] Not receiving antiretroviral therapies was significantly associated with restricted Medicaid eligibility.[77] This data suggests that improved insurance coverage to diagnose, screen, and treat pregnant individuals with HIV would help increase access to essential medications and reduce transmission of HIV from parent to child.[77]

Support groups

Bateganya et al. studied the impact of support groups for people living with HIV and found that 18/20 (90%) of papers reviewed showed support groups had a significant positive outcome.[78] Studies show that support groups reduce morbidity (having disease or symptoms of disease), reduce mortality (likelihood of dying), increase quality of life, and increase use of healthcare.[78] There is also research showing that support groups, in the short term, have a significant positive impact for pregnant women living with HIV.[79] Mundell et al. showed that pregnant women enrolled in a support group had 1) improved self-esteem, 2) a greater ability to cope with their medical diagnoses, and 3) were more likely to follow up with healthcare services and share their HIV diagnosis with others than those not enrolled in a support group.[79] This research suggests pregnant women living with HIV may benefit from peer support groups.

References

- "HIV Surveillance Report". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 2020.

- Children and Pregnant Women Living with HIV (PDF). UNAIDS. 2014. ISBN 978-92-9253-062-4.

- "Mother-to-child transmission of HIV". www.who.int. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA (June 2015). "Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015" (PDF). MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 64 (RR-03): 1–137. PMC 5885289. PMID 26042815.

- "Preventing Perinatal Transmission of HIV | NIH". hivinfo.nih.gov. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

- "ACOG Committee Opinion No. 752: Prenatal and Perinatal Human Immunodeficiency Virus Testing". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 132 (3): e138–e142. September 2018. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002825. PMID 30134428. S2CID 52070003.

- Panel on Treatment of Pregnant Women with HIV Infection and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. "Maternal HIV Testing and Identification of Perinatal HIV Exposure". Clinical Info HIV gov. Office of AIDS Research (OAR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- Levinson WE (2020). "Human Immunodeficiency Virus". In Levinson W, Chin-Hong P, Joyce EA, Nussbaum J, Schwartz B (eds.). Review of medical microbiology & immunology: a guide to clinical infectious diseases (Sixteenth ed.). New York. pp. 377–89. ISBN 978-1-260-11671-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "About HIV/AIDS". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020-11-03. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- Niu MT, Stein DS, Schnittman SM (December 1993). "Primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection: review of pathogenesis and early treatment intervention in humans and animal retrovirus infections". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 168 (6): 1490–501. doi:10.1093/infdis/168.6.1490. PMID 8245534.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Human (2018). "Immunodeficiency Virus Infection 111". In Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS (eds.). Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. American Academy of Pediatrics. pp. 459–476. ISBN 978-1-61002-146-3.

- "Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) to Reduce the Risk of Acquiring HIV During Periconception, Antepartum, and Postpartum Periods | Perinatal | ClinicalInfo". Clinical Info HIV gov. Office of AIDS Research (OAR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2021-01-27.

- "Prepregnancy Counseling". www.acog.org. Retrieved 2021-01-21.

- "Preconception Counseling and Care for Women of Childbearing Age with HIV". Clinical Info HIV gov. Office of AIDS Research (OAR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2021-01-21.

- "Evidence of HIV treatment and viral suppression in preventing the sexual transmission of HIV" (PDF). U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. December 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- Glynn JR, Buvé A, Caraël M, Kahindo M, Macauley IB, Musonda RM, et al. (December 2000). "Decreased fertility among HIV-1-infected women attending antenatal clinics in three African cities". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 25 (4): 345–52. doi:10.1097/00126334-200012010-00008. PMID 11114835. S2CID 22980353.

- van Leeuwen E, Prins JM, Jurriaans S, Boer K, Reiss P, Repping S, van der Veen F (2007-03-01). "Reproduction and fertility in human immunodeficiency virus type-1 infection". Human Reproduction Update. 13 (2): 197–206. doi:10.1093/humupd/dml052. PMID 17099206.

- Kushnir VA, Lewis W (September 2011). "Human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and infertility: emerging problems in the era of highly active antiretrovirals". Fertility and Sterility. 96 (3): 546–53. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.094. PMC 3165097. PMID 21722892.

- "An Opt-Out Approach to HIV Screening". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2015-11-13.

- "Routine Tests During Pregnancy". www.acog.org. Retrieved 2021-01-25.

- "Recommendations for Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnant HIV-1-Infected Women for Maternal Health and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- Branson BM, Owen SM, Wesolowski LG, Bennett B, Werner BG, Wroblewski KE, Pentella MA (2014-06-27). "Laboratory testing for the diagnosis of HIV infection: updated recommendations". doi:10.15620/cdc.23447.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Cornett JK, Kirn TJ (September 2013). "Laboratory diagnosis of HIV in adults: a review of current methods". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 57 (5): 712–8. doi:10.1093/cid/cit281. PMID 23667267.

- "British HIV Association guidelines for the management of HIV in pregnancy and postpartum 2018" (PDF). Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- Garcia PM, Kalish LA, Pitt J, Minkoff H, Quinn TC, Burchett SK, et al. (August 1999). "Maternal levels of plasma human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA and the risk of perinatal transmission. Women and Infants Transmission Study Group". The New England Journal of Medicine. 341 (6): 394–402. doi:10.1056/NEJM199908053410602. PMID 10432324.

- Thorne C, Patel D, Fiore S, Peckham C, Newell ML, et al. (European Collaborative Study) (February 2005). "Mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy" (PDF). Clinical Infectious Diseases. 40 (3): 458–65. doi:10.1086/427287. PMID 15668871.

- "Overview | General Principles Regarding Use of Antiretroviral Drugs during Pregnancy | Antepartum Care | Perinatal | ClinicalInfo". Clinical Info HIV gov. Office of AIDS Research (OAR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2021-01-25.

- "Antiretroviral Management of Newborns with Perinatal HIV Exposure or HIV Infection | Management of Infants Born to Women with HIV Infection | Perinatal | ClinicalInfo". Clinical Info HIV gov. Office of AIDS Research (OAR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2021-01-25.

- Townsend CL, Byrne L, Cortina-Borja M, Thorne C, de Ruiter A, Lyall H, et al. (April 2014). "Earlier initiation of ART and further decline in mother-to-child HIV transmission rates, 2000-2011". AIDS. 28 (7): 1049–57. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000212. PMID 24566097. S2CID 19123848.

- Hoffman RM, Black V, Technau K, van der Merwe KJ, Currier J, Coovadia A, Chersich M (May 2010). "Effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy duration and regimen on risk for mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Johannesburg, South Africa". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 54 (1): 35–41. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181cf9979. PMC 2880466. PMID 20216425.

- (HHS) Panel on Treatment of HIV-Infected Pregnant Women and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission, a working group of the Office of AIDS Research Advisory Council (OARAC). "HIV and Pregnancy" (PDF). aidsinfo.nih.gov. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- Panel on Treatment of HIV-Infected Pregnant Women and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. "Recommendations for Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnant HIV-1-Infected Women for Maternal Health and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States" (PDF). Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- National Consolidated Guidelines for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the management of HIV in children, adolescents and adults (PDF). National Department of Health, South Africa. April 2015.

- "When to Start Antiretroviral Therapy | HIV/AIDS Fact Sheets | Education Materials | AIDSinfo". AIDSinfo. Retrieved 2015-11-21.

- "Intrapartum Care for Women with HIV | Perinatal | ClinicalInfo". Clinical Info HIV gov. Office of AIDS Research (OAR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2021-01-25.

- Summary of Maternal Immunization Recommendations. ACOG and CDC. Published December 2018. Accessed 25 January 2021.

- "Vaccine Safety: Vaccines During Pregnancy FAQs". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 24 August 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- "Monitoring of the Woman and Fetus During Pregnancy | Antepartum Care | Perinatal | ClinicalInfo". Clinical Info HIV gov. Office of AIDS Research (OAR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2021-01-25.

- "Antiretroviral Drug Resistance and Resistance Testing in Pregnancy | Antepartum Care | Perinatal | ClinicalInfo". Clinical Info HIV gov. Office of AIDS Research (OAR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2021-01-25.

- "Hepatitis B Virus/HIV Coinfection | Special Populations | Antepartum Care | Perinatal | ClinicalInfo". Clinical Info HIV gov. Office of AIDS Research (OAR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2021-01-25.

- "Cytomegalovirus, Parvovirus B19, Varicella Zoster, and Toxoplasmosis in Pregnancy". www.acog.org. Retrieved 2021-01-25.

- "Table 10. Antiretroviral Drug Use in Pregnant Women with HIV: Pharmacokinetic and Toxicity Data in Human Pregnancy and Recommendations for Use in Pregnancy | ClinicalInfo". Clinical Info HIV gov. Office of AIDS Research (OAR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2021-01-27.

- "Panel on Treatment of Pregnant Women with HIV Infection and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Transmission in the United States" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- "Antiretroviral Drug Regimens and Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes | General Principles Regarding Use of Antiretroviral Drugs during Pregnancy | Antepartum Care | Perinatal | ClinicalInfo". Clinical Info HIV gov. Office of AIDS Research (OAR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2021-01-27.

- Wiysonge CS, Ndze VN, Kongnyuy EJ, Shey MS. Vitamin A supplements for reducing mother-to-child HIV transmission. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Sep 7;9(9):CD003648. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003648.pub4. PMID 28880995; PMCID: PMC5618453.

- Rothman KJ, Moore LL, Singer MR, Nguyen US, Mannino S, Milunsky A (November 1995). "Teratogenicity of high vitamin A intake". The New England Journal of Medicine. 333 (21): 1369–73. doi:10.1056/NEJM199511233332101. PMID 7477116.

- "Postpartum Follow-Up of Women with HIV | Perinatal | ClinicalInfo". Clinical Info HIV gov. Office of AIDS Research (OAR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- "Antiretroviral Management of Newborns with Perinatal HIV Exposure or HIV Infection | Pediatric ARV | ClinicalInfo". Clinical Info HIV gov. Office of AIDS Research (OAR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- "Diagnosis of HIV Infection in Infants and Children | Management of Infants Born to Women with HIV Infection | Perinatal | ClinicalInfo". Clinical Info HIV gov. Office of AIDS Research (OAR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- "Initial Postnatal Management of the Neonate Exposed to HIV | Management of Infants Born to Women with HIV Infection | Perinatal | ClinicalInfo". Clinical Info HIV gov. Office of AIDS Research (OAR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- Committee on Pediatric AIDS (February 2013). "Infant feeding and transmission of human immunodeficiency virus in the United States". Pediatrics. 131 (2): 391–6. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3543. PMID 23359577.

- "Breastfeeding: HIV". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. February 4, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- "Optimizing Support for Breastfeeding as Part of Obstetric Practice". www.acog.org. Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- "Counseling and Managing Women Living with HIV in the United States Who Desire to Breastfeed | Perinatal | ClinicalInfo". Clinical Info HIV gov. Office of AIDS Research (OAR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- "World Health Organization. Breastfeeding and HIV" (PDF). Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- WHO | Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. World Health Organization. June 30, 2013. p. 38. ISBN 978-92-4-150572-7.

- "HIV and Infant Feeding 2010: An Updated Framework for Priority Action". World Health Organization. 2012. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- "WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF infant feeding guidelines". www.unicef.org. Archived from the original on 2018-09-06. Retrieved 2018-09-06.

- Guideline: Updates on HIV and infant feeding (PDF). World Health Organisation, UNICEF. 2016.

- Iliyasu Z, Galadanci HS, Ibrahim YA, Babashani M, Mijinyawa MS, Simmons M, Aliyu MH (2017-05-27). "Should They Also Have Babies? Community Attitudes Toward Sexual and Reproductive Rights of People Living With HIV/AIDS in Nigeria". Annals of Global Health. 83 (2): 320–327. doi:10.1016/j.aogh.2017.05.001. PMID 28619407.

- Kontomanolis EN, Michalopoulos S, Gkasdaris G, Fasoulakis Z (2017-05-10). "The social stigma of HIV-AIDS: society's role". HIV/AIDS: Research and Palliative Care. 9: 111–118. doi:10.2147/HIV.S129992. PMC 5490433. PMID 28694709.

- "People Living with HIV Stigma Index: Asia Pacific Regional Analysis 2011". www.unaids.org. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- "Positive and pregnant – how dare you: a study on access to reproductive and maternal health care for women living with HIV in Asia: by Women of the Asia Pacific Network of People Living with HIV, March 2012". Reproductive Health Matters. 20 (sup39): 110–118. January 2012. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39646-8. ISSN 0968-8080.

- Roseman MJ, Ahmed A, Gatsi-Mallet J (2012). "'At the Hospital There are No Human Rights': Reproductive and Sexual Rights Violations of Women Living with HIV in Namibia". SSRN Working Paper Series. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2220800. hdl:2047/d20002882. ISSN 1556-5068.

- Kendall T, Albert C (January 2015). "Experiences of coercion to sterilize and forced sterilization among women living with HIV in Latin America". Journal of the International AIDS Society. 18 (1): 19462. doi:10.7448/IAS.18.1.19462. PMC 4374084. PMID 25808633.

- "Forced sterilisation as a human rights violation: recent developments". ijrcenter.org. 21 March 2019. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- "Government of the Republic of Namibia v LM and Others (SA 49/2012) [2014] NASC 19 (03 November 2014); | Namibia Legal Information Institute". namiblii.org. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- "Namibia Women Coerced into Being Sterilised". International Business Times UK. 2012-07-30. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- "Harvard Human Rights Law Journal – Litigating against the Forced Sterilization of HIV-Positive Women: Recent Developments in Chile and Namibia. 2010". Harvard Human Rights Journal. Namibia. 2010. doi:10.1163/2210-7975_HRD-9944-0037 – via BRILL.

- Madhi SA, Cutland CL, Kuwanda L, Weinberg A, Hugo A, Jones S, et al. (September 2014). "Influenza vaccination of pregnant women and protection of their infants". The New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (10): 918–31. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1401480. hdl:2263/42412. PMID 25184864.

- Solomon SS, Hawcroft CS, Narasimhan P, Subbaraman R, Srikrishnan AK, Cecelia AJ, et al. (May 2008). "Comorbidities among HIV-infected injection drug users in Chennai, India". The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 127 (5): 447–52. PMC 5638642. PMID 18653907.

- "Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Diagnoses of HIV/AIDS—33 States, 2001-2004". JAMA. 295 (13): 1508. 2006-04-05. doi:10.1001/jama.295.13.1508. ISSN 0098-7484.

- Salihu HM, Stanley KM, Mbah AK, August EM, Alio AP, Marty PJ (November 2010). "Disparities in rates and trends of HIV/AIDS during pregnancy across the decade, 1998-2007". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 55 (3): 391–6. doi:10.1097/qai.0b013e3181f0cccf. PMID 20729744. S2CID 34024641.

- Krawczyk CS, Funkhouser E, Kilby JM, Vermund SH (2009). "Delayed access to HIV diagnosis and care: Special concerns for the Southern United States". AIDS Care. 18 (Suppl 1): S35-44. doi:10.1080/09540120600839280. PMC 2763374. PMID 16938673.

- Enriquez M, Farnan R, Simpson K, Grantello S, Miles MS (2007). "Pregnancy, Poverty, and HIV". The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 3 (10): 687–693. doi:10.1016/j.nurpra.2007.08.015. ISSN 1555-4155.

- Krueger LE, Wood RW, Diehr PH, Maxwell CL (August 1990). "Poverty and HIV seropositivity: the poor are more likely to be infected". AIDS. 4 (8): 811–4. doi:10.1097/00002030-199008000-00015. PMID 2261136.

- Zhang S, Senteio C, Felizzola J, Rust G (December 2013). "Racial/ethnic disparities in antiretroviral treatment among HIV-infected pregnant Medicaid enrollees, 2005-2007". American Journal of Public Health. 103 (12): e46-53. doi:10.2105/ajph.2013.301328. PMC 3828964. PMID 24134365.

- Bateganya MH, Amanyeiwe U, Roxo U, Dong M (April 2015). "Impact of support groups for people living with HIV on clinical outcomes: a systematic review of the literature". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 68 (Supplement 3): S368-74. doi:10.1097/qai.0000000000000519. PMC 4709521. PMID 25768876.

- Mundell JP, Visser MJ, Makin JD, Kershaw TS, Forsyth BW, Jeffery B, Sikkema KJ (August 2011). "The impact of structured support groups for pregnant South African women recently diagnosed HIV positive". Women & Health. 51 (6): 546–65. doi:10.1080/03630242.2011.606356. PMC 4017076. PMID 21973110.

External links

- aidsinfo.nih.gov Archived 2021-03-22 at the Wayback Machine

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Government.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Government.