Democratic Party (Luxembourg)

The Democratic Party (Luxembourgish: Demokratesch Partei, French: Parti démocratique, German: Demokratische Partei), abbreviated to DP, is the major liberal[3][4][5][6] political party in Luxembourg. One of the three major parties, the DP sits on the centre-right,[7][8][9][10][11][12] with some centrist factions[7][8][9][10][11][12] holding moderate market liberal views combined with a strong emphasis on civil liberties, human rights, and internationalism.[13] The Democratic Party's traditional ideological spectrum was evaluated as conservative-liberal,[14] but now it is often evaluated as social-liberal.[4][5][15]

Democratic Party Demokratesch Partei | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Abbreviation | DP |

| Leader | Lex Delles[1] |

| Founded | 24 April 1955 |

| Headquarters | 2a, rue des Capucins L-1313 Luxembourg Luxembourg |

| Youth wing | Democratic and Liberal Youth |

| Ideology | Liberalism Social liberalism Conservative liberalism Pro-Europeanism |

| Political position | Centre to centre-right |

| Regional affiliation | Liberal Group[2] |

| European affiliation | Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe |

| International affiliation | Liberal International |

| European Parliament group | Renew Europe |

| Colours | Blue |

| Chamber of Deputies | 14 / 60 |

| European Parliament | 1 / 6 |

| Local councils | 135 / 722 |

| Benelux Parliament | 1 / 7 |

| Website | |

| http://www.dp.lu | |

Founded in 1955, the party is currently led by Lex Delles.[16] Its former president, Xavier Bettel, has been the Prime Minister of Luxembourg since 2013, leading the Bettel-Schneider government in coalition with the Luxembourg Socialist Workers' Party (LSAP) and The Greens. It is the second-largest party in the Chamber of Deputies, with fourteen seats out of sixty, having won 17.8% of the vote at the 2023 general election, and has two seats in the European Parliament out of six. The party's stronghold is around Luxembourg City;[17] it has provided the city's Mayor since 1970.

The party has often played the minor coalition partner to the Christian Social People's Party (CSV). In Gaston Thorn and Xavier Bettel, the DP has provided the only Prime Ministers of Luxembourg since 1945 not to be affiliated with the CSV (1974–79 and 2013–present). The party is a member of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE) and the Liberal International. The party has been one of the most influential liberal parties in Europe, due to its strength, its regular involvement in government, its role in international institutions, and Thorn's leadership.[18]

History

Emergence as major party

Although the party traces its history back to the foundation of the Liberal League in 1904, it was founded in its current form on 24 April 1955. It was the successor to the Democratic Group, which had grown out of the major group of war-time liberal resistance fighters, the Patriotic and Democratic Group. The DP spent the majority of the 1950s and 1960s, under the leadership of Lucien Dury and then Gaston Thorn, establishing itself as the third major party, ahead of the Communist Party.

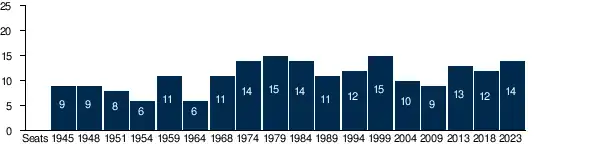

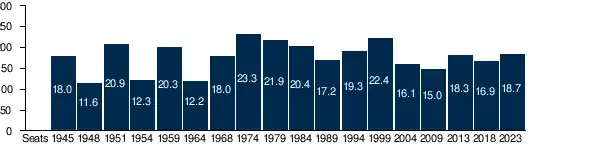

At the time of its foundation, the party had six seats in the Chamber of Deputies. At the following election in 1959, the DP won 11 seats, allowing it to serve as a minor role in a grand coalition with the Christian Social People's Party (CSV) and Luxembourg Socialist Workers' Party (LSAP). However, in 1964, the party went back to six seats. In 1968, the DP absorbed the anti-establishment Popular Independent Movement.[19] In that year's election, the party benefited from a tide of moderates shifting from an increasingly radical LSAP,[19] returned to 11 seats, and consequently entered into government with the CSV under Prime Minister Pierre Werner.

Government

The DP remained in coalition with the CSV until 1974, when it experienced a surge in support in the 1974 general election, to 22.2% of the vote and 14 seats. This political upset gave it the opportunity to enter into coalition negotiations with the second-placed LSAP.[20] Surprisingly, in the negotiations, the DP got the upper hand, securing the most ministerial positions and departments, as well as the premiership itself under Gaston Thorn.[15]

The formation of Thorn's government, however, coincided with the beginning of an economic crisis,[21] and the government was occupied mostly with the restructuring of the steel industry whilst attempting to avoid mass unemployment.[21]

Despite this, the coalition managed to push through major reforms of social policy,[22] including abolishing capital punishment (1974), allowing no-fault divorce (1975) and broadening at-fault divorce (1978), and legalising abortion (1978).[23] In 1977, the government abandoned plans to build a nuclear power plant at Remerschen,[23] of which the DP had been the primary advocate.[24] When PM, in 1975, Thorn sat as President of the United Nations General Assembly.

Since 1979

In 1979, Thorn went head-to-head with Werner, with the LSAP serving a supporting role to the DP.[25] Both the CSV ended victorious, gaining six seats, and the LSAP's loss of three seats made it impossible for the DP to renew the coalition with them. As a result, Werner formed a coalition with the DP, with Thorn as Deputy Prime Minister.[26] In the first European election in 1979, the DP won 2 seats: an achievement that it hasn't matched since. In 1980, Thorn was named the new President of the European Commission, and was replaced by Colette Flesch.

The 1984 general election saw the DP's first electoral setback in twenty years.[25] The DP lost one seat, standing on 14, whilst the resurgence of the LSAP meant it overtook the Democratic Party once again. The LSAP formed a coalition with the CSV, with Jacques Poos serving as Deputy Prime Minister to Jacques Santer. This was renewed twice again, and the DP remained out of government until 1999.

After the 1999 general election, the DP became the second-largest party in the Chamber of Deputies once again, with 15 seats. It also overtook the LSAP in vote share for the first time ever. This allowed it to displace the LSAP as the CSV's coalition partner, with Lydie Polfer as Deputy Prime Minister. As a result of the 2004 general election, the DP lost 5 seats, bringing its total down to 10. The party also lost its place as the coalition partner back to the LSAP, and remained in opposition since until 2013. In the 2013 general election, held early due to the collapse of the second Juncker–Asselborn government, the party acquired 13 deputies with 18.3% of the vote, becoming joint second-largest party along with the LSAP. In October 2013 the DP negotiated a three-party coalition government with the LSAP and The Greens,[27] and on 4 December 2013 the Bettel-Schneider government was sworn in, with DP leader Xavier Bettel serving as Prime Minister.[28]

Ideology

The Democratic Party sits on the moderate centre-right of the political spectrum in Luxembourg. Since the late 1960s, thanks to the secularisation of Luxembourg and the CSV, the party has moved gradually towards the centre, to allow it to form coalitions with either the CSV or LSAP.[29][30] Now, it could be seen to be to the left of the CSV, in the centre, and with more in common with the British Liberal Democrats or German Free Democratic Party than with liberal parties in Belgium or the Netherlands.[29][31] However, the CSV usually prefers forming coalitions with the LSAP to those with the DP, pushing the DP to the economically liberal right.[7]

In economic policies, the DP is a strong supporter of private property rights, free trade, and the free market, although under Thorn's government, the DP greatly increased public sector employment.[32] Taxation plays a major role in the party platform. It is also a supporter of agriculture, particularly the wine industry.[32] It long advocated the advancement of nuclear power, but scrapped plans to build a plant at Remerschen, and now supports renewable alternatives, although not opposing nuclear power in principle.[24] Indicating its priorities, when in government, the DP has usually or always controlled ministries in charge of Transport, Public Works, the Middle Class, the Civil Service, and Energy.[33]

The DP is the most outspoken party in support of civil liberties. Between 1974 and 1979, it legalised abortion and divorce, and abolished the death penalty.[23] It also focuses its attention on the issues of minority groups, particularly migrant groups, but also homosexuals and single mothers.[32] Unlike the Catholic CSV, the DP is notably anti-clerical, which gives it more importance than its electoral performances would suggest.[30]

The DP has led the CSV and LSAP in becoming more internationalist in outlook, focusing on the European Union, environmentalism, and advocacy of human rights abroad.[32] It is the most vocal supporter of European integration, even in a particularly pro-EU country.[34] The party puts great emphasis on the role of the United Nations, and Thorn served as President of the UN General Assembly. The party is centrist on national security, supporting membership of NATO, but having worked to end conscription.[34]

Political support

The DP has been consistent in its advocacy of the middle class,[32] and consequently has a very distinctive class profile.[35] When in government, the DP has always held the office of Minister for the Middle Class.[33] Most DP supporters are civil servants, white-collar workers, self-employed people, and those on high incomes.[17] This group has been fast-growing, further focusing the party's electoral socio-economic appeal.[31]

The party's most successful areas electorally are Luxembourg City and its wealthy suburbs, where those groups are concentrated.[31] The Mayor of Luxembourg City has come from the DP since 1970, and the party and its liberal predecessors have been out of the office for only seven years since the foundation of the Liberal League in 1904. The city lies in the Centre constituency, where the DP challenges the CSV for the most seats. However, the party also has some traditional following in Est and the Nord,[31] consistently coming second in each.

The party has notably more support amongst young people,[35] whilst the CSV, LSAP, and (recently) the Alternative Democratic Reform Party tend to receive the votes of older people.[17] Unlike the CSV and LSAP, the DP is not affiliated to a major trade union. The party is particularly popular amongst male voters.[17] Despite its anti-clericalism, DP voters are no less religiously affiliated than the general population.[35]

Election results

Chamber of Deputies

| Election | Votes | % | Elected seats | Seats after | +/– | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1945 | 366,860 | 18.0 (#3) | 9 / 51 |

New | Coalition | |

| 1948[lower-alpha 1] | 97,415 | 11.6 (#3) | 3 / 26 |

9 / 51 |

Coalition | |

| 1951[lower-alpha 1] | 215,511 | 20.9 (#3) | 5 / 26 |

8 / 52 |

Opposition | |

| 1954 | 255,522 | 12.3 (#3) | 6 / 52 |

Opposition | ||

| 1959 | 448,387 | 20.3 (#3) | 11 / 52 |

Coalition | ||

| 1964 | 280,644 | 12.2 (#3) | 6 / 56 |

Opposition | ||

| 1968 | 430,262 | 18.0 (#3) | 11 / 56 |

Coalition | ||

| 1974 | 668,043 | 23.3 (#3) | 14 / 59 |

Coalition | ||

| 1979 | 648,404 | 21.9 (#2) | 15 / 59 |

Coalition | ||

| 1984 | 614,627 | 20.4 (#3) | 14 / 64 |

Opposition | ||

| 1989 | 498,862 | 17.2 (#3) | 11 / 60 |

Opposition | ||

| 1994 | 548,246 | 19.3 (#3) | 12 / 60 |

Opposition | ||

| 1999 | 632,707 | 22.4 (#2) | 15 / 60 |

Coalition | ||

| 2004 | 460,601 | 16.1 (#3) | 10 / 60 |

Opposition | ||

| 2009 | 432,820 | 15.0 (#3) | 9 / 60 |

Opposition | ||

| 2013 | 597,879 | 18.3 (#3) | 13 / 60 |

Coalition | ||

| 2018 | 597,080 | 16.9 (#3) | 12 / 60 |

Coalition | ||

| 2023 | 703,833 | 18.7 (#3) | 14 / 60 |

Coalition | ||

- Partial election. Only half of the seats were up for renewal.

European Parliament

| Election | Votes | % | Seats | +/– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 274,307 | 28.1 (#2) | 2 / 6 |

|

| 1984 | 218,481 | 22.1 (#3) | 1 / 6 |

|

| 1989 | 198,254 | 19.9 (#3) | 1 / 6 |

|

| 1994 | 190,977 | 18.8 (#3) | 1 / 6 |

|

| 1999 | 207,379 | 20.5 (#2) | 1 / 6 |

|

| 2004 | 162,064 | 14.9 (#4) | 1 / 6 |

|

| 2009 | 210,107 | 18.7 (#3) | 1 / 6 |

|

| 2014 | 173,255 | 14.8 (#3) | 1 / 6 |

|

| 2019 | 268,910 | 21.4 (#1) | 2 / 6 |

Presidents

The leader of the party is the president. Below is a list of presidents of the Democratic Party, and its predecessors, since 1948.

- Lucien Dury (1948–1952)

- Eugène Schaus (1952–1959)

- Lucien Dury (1959–1962)

- Gaston Thorn (1962–1969)

- René Konen (1969–1971)

- Gaston Thorn (1971–1980)

- Colette Flesch (1980–1989)

- Charles Goerens (1989–1994)

- Lydie Polfer (1994–2004)

- Claude Meisch (2004–2013)

- Xavier Bettel (2013–2015)

- Corinne Cahen (2015–2022)

- Lex Delles (2022–)

See also

Footnotes

- "The party". dp.lu. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- "Politieke fracties". Benelux Parliament (in Dutch). Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- Nordsieck, Wolfram (2018). "Luxembourg". Parties and Elections in Europe.

- José Magone (26 August 2010). Contemporary European Politics: A Comparative Introduction. Routledge. p. 436–. ISBN 978-0-203-84639-1. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Georgios Terzis (2007). European Media Governance: National and Regional Dimensions. Intellect Books. p. 135–. ISBN 978-1-84150-192-5. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Bale, Tim (2021). Riding the populist wave: Europe's mainstream right in crisis. Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-009-00686-6. OCLC 1256593260.

- Dumont et al (2003), p. 412

- Jacobs, Francis (1989). Western European Political Parties: A Comprehensive Guide. London: Longman. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-582-00113-8.

- Country by Country. London: Economist Intelligence Unit. 2003. p. 96.

- Stalker, Peter (2007). A Guide to the Counties of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-19-920271-3.

- Josep M. Colomer (24 July 2008). Comparative European Politics. Taylor & Francis. p. 221–. ISBN 978-0-203-94609-1. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- Xenophon Contiades (20 December 2012). Engineering Constitutional Change: A Comparative Perspective on Europe, Canada and the USA. Routledge. p. 250–. ISBN 978-1-136-21077-8. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Hearl (1988), p. 392–3

- Hans Slomp (30 September 2011). Europe, A Political Profile: An American Companion to European Politics. ABC-CLIO. p. 477. ISBN 978-0-313-39182-8. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- Hearl (1988), p. 386

- "The party". dp.lu. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- Schulze (2007), p. 812

- Hearl (1988), p. 376

- "Luxembourg" (PDF). Inter-Parliamentary Union. 2000. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- Thewes (2006), p. 182

- Thewes (2006), p. 186

- Thewes (2006), p. 187

- Thewes (2006), p. 188

- Jacobs, Francis (1989). Western European Political Parties: A Comprehensive Guide. London: Longman. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-582-00113-8.

- Hearl (1988), p. 382

- Thewes (2006), p. 192

- "Chronicle.lu - LSAP, DP & Déi Gréng to Commence Coalition Negotiations". www.chronicle.lu. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- "New Luxemburg Government Sworn In". BrusselsDiplomatic. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- Dumont et al (2003), p. 400

- Hearl (1987), p. 255

- Hearl (1987), p. 256

- Hearl (1988), p. 392

- Dumont et al (2003), p. 424

- Hearl (1988), p. 393

- Hearl (1988), p. 390

References

- Dumont, Patrick; De Winter, Lieven (2003). "Luxembourg: Stable coalition in a pivotal party system". In Wolfgang C., Müller; Strom, Kaare (eds.). Coalition Governments in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 399–432. ISBN 978-0-19-829761-1.

- Hearl, Derek (1987). "Luxembourg 1945–82: Dimensions and Strategies". In Budge, Ian; Robertson, David; Hearl, Derek (eds.). Ideology, Strategy, and Party Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 254–69. ISBN 978-0-521-30648-5.

- Hearl, Derek (1988). "The Luxembourg Liberal Party". In Kirchner, Emil Joseph (ed.). Liberal Parties in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 376–95. ISBN 978-0-521-32394-9.

- Thewes, Guy (October 2006). Les gouvernements du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg depuis 1848 (PDF) (in French) (2006 ed.). Luxembourg City: Service Information et Presse. ISBN 978-2-87999-156-6. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- Schulze, Isabelle (2007). "Luxembourg: An Electoral System with Panache". In Immergut, Ellen M.; Anderson, Karen M.; Schulze, Isabelle (eds.). The Handbook of West European Pension Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 804–53. ISBN 978-0-19-929147-2.