Early Germanic warfare

Warfare seems to have been a constant in Germanic society, and archaeology indicates this was the case prior to the arrival of the Romans in the 1st century BCE.[1] Wars were frequent between and within the individual Germanic peoples.[2] The early Germanic languages preserve various words for "war", and they did not necessarily clearly differentiate between warfare and other forms of violent interaction.[3] The Romans note that for the Germans, robbery in warfare was not shameful, and most Germanic warfare both against Rome and against other Germanic peoples was motivated by the potential to acquire booty.[4][5]

.jpg.webp)

Sources

Historical descriptions of the warfare of the Germanic peoples depend entirely on Greco-Roman sources, and this is the aspect of Germanic society that Greco-Roman sources discuss the most.[6] Besides Julius Caesar's Bellum Gallicum (1st century BCE), there are two accounts that might apply to the Germanic peoples in general: chapter 6 of Tacitus's Germania (c. 100 CE) and book 11 of the Strategikon of Maurice (6th century CE).[7] However, the accuracy of these depictions has been questioned, and it is impossible to show archaeologically how the Germani fought.[5] Archaeology has yielded large amounts of Germanic weaponry, giving at a sense of their equipment.[8]

Military history

Archaeological records indicate that the arrival of the Corded Ware culture in Northern Europe was accompanied by large-scale migration and warfare. After a period of amalgamation, the Nordic Bronze Age emerged, which appears to have been a time of relative peace.[8]

The military situation in the Germanic world was radically changed with the emergence of the Iron Age and the late centuries BC. For close to a thousand years afterward, the Germanic world was characterized by almost continuous warfare and large-scale migration.[8]

Though often defeated by the Romans, the Germanic tribes were remembered in Roman records as fierce combatants, whose main downfall was that they failed to join together into a collective fighting force under a unified command, which allowed the Roman Empire to employ a "divide and rule" strategy against them.[9]

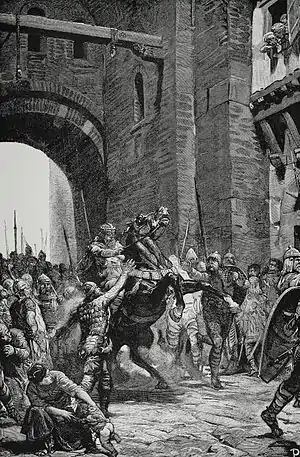

On occasions when the Germanic tribes worked together, the results were impressive. Three Roman legions were ambushed and destroyed by an alliance of Germanic tribes headed by Arminius at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 CE. As a result, the Roman Empire made no further concerted attempts at conquering Germania beyond the Rhine.[10]

During the 4th and 5th centuries CE, Visigoths and Vandals militarily organized themselves to sufficiently challenge and sack Rome in 410 AD and again in 455 AD. Then in 476 AD, the last Roman emperor was deposed by the Germanic warrior Odoacer, an event which effectively ended Roman predominance in Western Europe.[11] Germanic tribes eventually overwhelmed and conquered the ancient world. That military transition was additionally spurred by the arrival of the Vikings from Scandinavia in the 8th to 10th centuries, giving rise to modern Europe and medieval warfare.[12]

The later military development of armored knights and fortified castles was a response in part to the relentless plundering and raiding by the Vikings, which meant that the Germanic tribes who had settled mainland Europe and the British Isles had to adapt themselves so as to combat another wave of Germanic aggression.[13]

Armies and retinues

The core of the army is imagined as having been formed by the comitatus (retinue) of a chief, a term used in ancient sources that has many possible meanings.[15] Tacitus describes it as a group of warriors (comites) who follow a leader (princeps).[16] Heiko Steuer argues that a comitatus might refer to any group of warriors held together by mutual agreement and desire for booty, and that these were political, rather than ethnic or tribal groups.[17] As retinues grew larger, their names could become associated with entire peoples. Many retinues functioned as auxilia (mercenary units in the Roman army).[18]

Germanic armies were probably not large, with numbers such as an army of 100,000 Suevi claimed by Caesar being literary and propagandistic exaggerations.[19] Scholars can extrapolate numbers from 500–600 to 1600 per war band from later sources.[20] Older scholarship sometimes supposed that all the men in a "tribe" formed the army, but this would have been logistically impossible in a premodern society.[21] Steuer, while noting Germanic victories against large Roman forces, estimates the typical war band to have been no larger than 3000 men, while estimating that only as many of 1,800 may have participated in a campaign.[22] In later times, as the population of Germania grew, the armies grew larger.[23] Most warriors were probably unmarried men. Tacitus and Ammianus Marcellinus (4th century CE) indicate that armies included both young men and older, more experienced warriors.[21] By the early Middle Ages, armies were mostly composed of a distinct warrior class that relied on peasants for support.[24]

Tactics and organization

Roman sources stress, perhaps partially as a literary topos, that the Germanic peoples fought without discipline, with Tacitus in particular stating that Germanic war-leaders achieved more by example than by command.[25][26] Tacitus claims that Germanic armies were not divided into units like Roman ones, while Maurice emphasizes that informal units were formed in the army based on kinship.[27] Steuer, however, notes that many Germani served in the Roman army or as imperial bodyguards and thus would have been familiar with the organization of the Roman military. He argues that Germanic armies may have been organized in a manner not dissimilar to Roman armies.[28]

In antiquity, Germanic warriors fought mostly on foot.[29] Germanic infantry fought in tight formations in close combat, in a style that Steuer compares to the Greek phalanx.[30] Tacitus mentions a single formation as used by the Germani, the wedge (Latin: cuneus).[27] Men probably practiced the use of weapons beginning in their youth. When fighting the Roman legions, Germanic warriors seem to have preferred to attack from ambush, which would require organization and training. [5]

In the Roman period, mounted horsemen were usually limited to chiefs and their immediate retinues,[29] who may have dismounted to fight.[31] Some Roman sources such as Ammianus indicate a Germanic distrust of cavalry before the 6th century.[6] However, Tacitus mentions Germani fighting both on foot and on horseback, Caesar is known to have maintained a group of Germanic cavalry, and other sources speak of the excellent horsemanship of groups such as the Alemanni.[19] East Germanic peoples such as the Goths developed cavalry forces armed with lances due to contact with various nomadic peoples, so that the armies of Theodoric the Great were primarily horsemen.[32]

Forms of warfare

The three main types of warfare carried out during the Germanic Iron Age were feuds, raids and total war involving the entire tribe.[8]

Feuds

The prevalence of feuds in early Germanic warfare is well attested in the Sagas of Icelanders and other Germanic poems such as Beowulf. Since quarrels between individuals were at the time not regulated by any form of tribal law, feuds became in many cases the only way to obtain remedy for an injury.[8]

Raiding

Raids were typically carried out by the early Germanic peoples either for the purpose of acquiring booty or for scouting for areas suitable for colonization.[8]

Such raids were typically organized by individual leaders who would invite all who were interested in joining him on his quest.[8]

According to Caesar, a Germanic chieftain would typically announce a raid at the popular assembly and call for volunteers. Such raids did not necessarily involve the entire tribe, but must rather be considered private ventures. According to Tacitus, chieftains would utilize raids as a form of military training.[8]

The purpose of a raid was not to gain territory, but rather to capture resources and secure prestige. These raids were conducted by irregular troops, often formed along family or village lines, in groups of 10 to about 1,000.[33] Large bodies of troops, while figuring prominently in the history books, were the exception rather than the rule of ancient warfare. Thus a typical Germanic force might consist of 100 men with the sole goal of raiding a nearby Germanic or foreign village. Thus, most warfare was at their Germanic neighbors.[33]

Larger migrations were generally preluded by raids. A significant example of this is the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, which had been preceded for centuries by naval raids on Roman Britain.[8]

Cavalry was rarely used by Germanic raiders.[8]

Total war

Wars involving entire tribes were uncommon in the Germanic world until the Iron Age. One of the earliest Germanic peoples involved in such warfare were the Bastarnae, who are mentioned in classical sources as battling the Illyrians in Southeast Europe in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC.[8]

When engaged in total war, Germanic armies often consisted of more than 50 percent noncombatants, as displaced people would travel with large groups of soldiers, the elderly, women and children.[33]

In Getica, the 6th century Gothic historian Jordanes mentions a series of mass-migrations of the Goths from Scandinavia towards the Black Sea, but the accuracy of his writing has been put up to question. Other major tribal migrations taking place in the Migration Period include that of the Vandals, Lombards, Burgundians and Anglo-Saxons. During such migrations the entire tribe would move along with their belongings on ox-drawn wagons, not unlike the American pioneers centuries later.[8] When such folk-armies were forced to fight, a wagon fort would be established, where the women and children were provided shelter.[8] Such large-scale migrations required skilled leadership. Many of the most famous early Germanic kings, such as Alaric I, Theodoric the Great, Genseric and Alboin, are remembered for leading their people on such migrations.[8]

The earliest of Germanic mass migrations are not recounted in classical literature, and clues about such events can only be derived from archaeological discoveries.[8]

Aftermath of a battle

Victory

After a victorious battle, Germanic warriors would normally attend only the dead and wounded of their own side. Enemy dead would generally be left to be devoured by birds and beasts of prey. This process is described vividly in many pieces of early Germanic literature.[8]

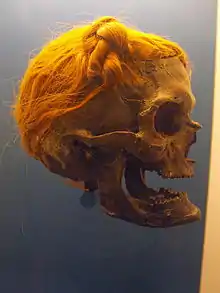

In case of victory, the booty would be divided among the troops, often by the casting of lots. Sometimes the booty, including prisoners, would be sacrificed to the god of war. This was infamously done by the Cimbri to Roman soldiers captured during the Cimbrian War.[8]

Defeat

Legitimacy for Germanic chieftains resided in their ability to successfully lead armies to victory. Defeat on the battlefield at the hands of the Romans or other barbarians often meant the end of a ruler and in some cases, being absorbed by "another, victorious confederation."[34]

It was reported in Roman sources that upon being defeated, Germanic women would kill their own children and commit suicide in order to avoid slavery. This was done by the Cimbri women following the defeat of their tribe by the Romans at the Battle of Vercellae in 101 BC.[8]

Cavalry

.jpg.webp)

While Germanic warfare emphasized the use of infantry, they were quite adept at the training and use of cavalry. In Germanic warfare, cavalry was generally used for reconnaissance, flanking, the pursuit of fleeing enemies and other special tasks.[8]

When Germanic tribes were on the march, their wagons would generally be protected by cavalry. Early Germanic chieftains were typically mounted. This is attested from numerous horse burials in the graves of Germanic leaders.[8]

Early Germanic cavalrymen commonly used spurs to properly control the horse. The stirrup was later introduced. This enabled the easier mounting and maintenance of balance. The fact that the stirrup was introduced at such a late date is a testimony to the excellent horsemanship of Germanic riders.[8]

Caesar notes that the Suebi would attach a fast-running warrior to each cavalryman, who could assist the latter with both defense and offense.[8]

Caesar considered Germanic cavalrymen superior to those of the Romans, and was thus forced to recruit Germanic mercenaries to compensate for this inferiority. The Germanic horses were however of smaller size than those of the Romans, and Germanic cavalrymen in Roman service were thus compelled by Caesar to ride Roman horses.[8][35]

Naval warfare

Naval warfare became an important component of Germanic warfare, particularly raiding. Ships were ideal for raiding because they enabled increased mobility and secrecy, which was essential for the success of a raid.[8]

For the early Germanic peoples, boats were primarily used for transportation. Certain tribes along the North Sea coast, such as the Saxons, fought naval battles during their raids on Roman territory. During the Viking Age the North Germanic peoples mastered the construction of the Viking ship and excelled at naval warfare.[8]

Siege and fortification

Roman sources mention that the Germanic peoples generally avoided walled towns and fortresses during their campaigns on Roman soil. Ammianus reports that they regarded cities as "tombs surrounded by nets".[36] This was most likely because the Germani did not have proper siege equipment; with the exception of the Vandals in North Africa, Germanic sieges seem to have been generally unsuccessful, with the unsuccessful besieging of the Emperor Julian in Sens in 356 breaking off after only thirty days.[37]

Older scholarship often said that the Germani possessed no fortresses of their own, however the existence of fortifications have been shown archaeologically, as well as larger earthworks meant to protect entire stretches of territory.[38] Tacitus, in his Annales, portrays the Cheruscan leader Segestes as besieged by Arminius in 15 CE (Annales I.57). Steuer believes that the siege was likely at a fortified farmstead of some kind, a type of fortification well-attested in Germania.[39] Larger fortified towns (Latin: oppida), found as far north as modern central Germany, are often identified as "Celtic" by archaeologists, although this cannot be clearly established.[40] However, fortified settlements are also found in northern Germany at Wittorf, near Osnabrück, in Jutland, and on Bornholm.[41] Hilltop fortifications, which Steuer calls "castles", are also attested from the pre-Roman Iron Age (5th/4th–1st century BCE) onward.[42]

Logistics

A key advantage of early Germanic armies was their mobility. For long-term conflicts they would usually bring all their supplies with them. For short term engagements, they brought with them few supplies and rather lived off the land. This would often cause severe devastation to areas in which Germanic warriors fought.[8]

For logistical reasons, early Germanic peoples generally carried out war in summer, but as they expanded southwards at the expense of the Romans, they were able to fight in the winter as well.[8]

Chariotry

Unlike their Celtic neighbors, the use of chariots was not widespread among Iron Age Germanic peoples.[43] Germanic peoples had used the horse-drawn war-chariot in the Bronze Age, but later gave it up.[44]

Mercenary activity

Germanic warriors frequently fought as mercenaries in the Roman army. Some of these mercenaries, such as Stilicho, rose to prominent positions. According to Francis Owen, the Western Roman Empire would have collapsed much earlier without such mercenaries.[8]

Returning Germanic mercenaries in the Roman army brought back many Roman products to their communities. This had a major impact on Germanic culture.[45]

Armament

Archaeological finds, mostly in the form of grave goods, indicate that a sort of standardized Germanic warrior's kit had developed by the pre-Roman Iron Age, with warriors armed with spear, shield, and increasingly with swords.[30] Higher status individuals were often buried with spurs for riding.[31] Tacitus likewise reports that most Germanic warriors used the sword or the spear, and he gives the native word framea for the latter.[46] Tacitus says that the sword was not frequently used.[47] Archaeological finds show spearheads and swords with one cutting edge were generally produced natively in Germania, while swords with two cutting edges were more frequently of Roman manufacture.[48] Axes become more common in warrior graves from the 3rd century CE onward, as well as bows and arrows.[49]

Tacitus claims that many Germanic warriors went into battle naked or scantily clad, and that for many the only defensive equipment was a shield, something also shown on Roman depictions of Germanic warriors.[47] The Germanic word for breastplate, brunna, is of Celtic origin, indicating that it was borrowed prior to the Roman period.[50] The only archaeological evidence for helmets and chain mail shows them to be of Roman manufacture.[51] "Normal" warriors seem to have acquired their own kit, while members of a comitatus appear to have been armed by their leaders from centralized workshops.[52]

See also

Notes

References

- Steuer 2021, p. 673.

- Steuer 2021, p. 794.

- Bulitta & Springer 2010, pp. 665–667.

- Bulitta & Springer 2010, p. 674.

- Steuer 2021, p. 674.

- Murdoch 2004, p. 62.

- Bulitta & Springer 2010, p. 676.

- Owen 1960, pp. 119–133.

- Archer et al. 2008, p. 105.

- Roberts 1996, pp. 65–66.

- Daniels & Hyslop 2014, p. 85.

- Waldman & Mason 2006, p. 836.

- Waldman & Mason 2006, pp. 322–323.

- Steuer 2021, p. 683.

- Steuer 2021, p. 785.

- Green 1998, p. 107.

- Steuer 2021, p. 786.

- Steuer 2021, pp. 793–794.

- Bulitta & Springer 2010, p. 677.

- Steuer 2021, p. 675.

- Bulitta & Springer 2010, pp. 680–681.

- Steuer 2021, pp. 575–676.

- Steuer 2021, p. 680.

- Bulitta & Springer 2010, pp. 681–682.

- Green 1998, pp. 68–69.

- Murdoch 2004, p. 63.

- Bulitta & Springer 2010, pp. 678–679.

- Steuer 2021, pp. 676–678.

- Todd 2009, p. 35.

- Steuer 2021, p. 663.

- Steuer 2021, p. 672.

- Todd 2009, p. 42.

- Geary 1999, p. 113.

- Geary 1999, p. 112.

- Todd 2009, pp. 36–37.

- Murdoch 2004, p. 64.

- Todd 2009, pp. 40–41.

- Steuer 2021, p. 307.

- Steuer 2021, pp. 308–309.

- Steuer 2021, p. 309.

- Steuer 2021, pp. 310–316.

- Steuer 2021, pp. 316–335.

- Todd 2009, p. 37.

- Owen 1960, pp. 166–174.

- Owen 1960, pp. 174–178.

- Green 1998, p. 69.

- Green 1998, p. 70.

- Steuer 2021, p. 662.

- Todd 2009, p. 41.

- Green 1998, p. 71.

- Steuer 2021, p. 661.

- Steuer 2021, p. 667.

Bibliography

- Archer, Christon I.; Ferris, John R.; Herwig, Holger; Travers, Timothy H. E. (2008). World History of Warfare. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1941-0.

- Bémont, Charles; Monod, Gabriel (2012). Medieval Europe, 395–1270. Lecturable [Kindle Edition]. ASIN B00ASEDPFA.

- Bulitta, Brigitte; Springer, Matthias; et al. (2010) [2000]. "Kriegswesen". Germanische Altertumskunde Online. de Gruyter. pp. 667–746.

- Daniels, Patricia; Hyslop, Stephen (2014). Almanac of World History. Washington DC: National Geographic. ISBN 978-0-7922-5911-4.

- Geary, Patrick J. (1999). "Barbarians and Ethnicity". In G.W. Bowersock; Peter Brown; Oleg Grabar (eds.). Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-51173-6.

- Green, Dennis H. (1998). Language and History in the Early Germanic World (2001 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79423-7.

- Heather, Peter (2005). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515954-7.

- Murdoch, Adrian (2004). "Germania Romana". In Murdoch, Brian; Read, Malcolm (eds.). Early Germanic Literature and Culture. Camden House. pp. 55–71.

- Owen, Francis (1960). The Germanic People. New York: Bookman Associates.

- Roberts, J. M. (1996). A History of Europe. New York: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-9658431-9-5.

- Santosuo, Antonio (2004). Barbarians, Marauders, and Infidels: The Ways of Medieval Warfare. New York: MJF Books. ISBN 978-1-56731-891-3.

- Steuer, Heiko (2021). Germanen aus Sicht der Archäologie: Neue Thesen zu einem alten Thema. de Gruyter.

- Todd, Malcolm (2009) [1999]. The Early Germans. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781405137560.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4964-6.

Further reading

- France, John; DeVries, Kelly (2008). Warfare in the Dark Ages. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0754625575.

- Haywood, John (2006). Dark Age Naval Power: A Reassessment of Frankish and Anglo-Saxon Seafaring Activity. Anglo-Saxon Books. ISBN 1898281432.

- Härke, Heinrich (February 1990). ""Warrior Graves"? The Background of the Anglo-Saxon Weapon Burial Rite". Past & Present. Oxford University Press (126): 22–43. JSTOR 650808.

- MacDowall, Simon (2000). Germanic Warrior 236-568 AD. Blumsbury USA. ISBN 1841761524.

- MacDowall, Simon (2005). Adrianopole, AD 378: The Goths Crush Rome's Legions. Praeger. ISBN 027598835X.

- Musset, Lucien (1975). The Germanic Invasions: The Making of Europe, AD 400-600. Paul Elek. ISBN 023617620X.

- Powell, Lindsay (2014). Roman Soldier vs Germanic Warrior: 1st Century AD. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1472803511.

- Price, Arnold Hereward (1996). Germanic Warrior Clubs: An Inquiry Into the Dynamics of the Era of Migrations and Into the Antecedents of Medieval Society. UVT. ISBN 3924898219.

- Shadrake, Ben; Shadrake, Susanne (1997). Barbarian warriors: Saxons, Vikings, Normans. Brassey's.

- Speidel, Michael P. (Fall 2002). "Berserks: A History of Indo-European "Mad Warriors"". Journal of World History. University of Hawaii Press. 13 (2): 253–290. doi:10.1353/jwh.2002.0054. JSTOR 20078974.

- Speidel, Michael P. (2004). Ancient Germanic Warriors: Warrior Styles from Trajan's Column to Icelandic Sagas. Routledge. ISBN 1134384203.

- Steuer, Heiko (2004). "Warrior Bands, War Lords, and the Birth of Tribes and States in the First Millennium AD in Middle Europe". In Otto, Ton; Thrane, Henrik; Vandkilde, Helle (eds.). Warfare and Society: Archaeological and Social Anthropological Perspectives. ISD LLC. pp. 227–236. ISBN 8779349358.

- Thompson, E. A. (November 1958). "Early Germanic Warfare". Past & Present. Oxford University Press (14): 2–29. JSTOR 650090.