Morini

The Morini (Gaulish: 'sea folk, sailors') were a Belgic coastal tribe dwelling in the modern Pas de Calais region, around present-day Boulogne-sur-Mer, during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

Name

They are mentioned as Morini by Caesar (mid-1st c. BC) and Pliny (1st c. AD),[1] Morinoì (Μορινοὶ) by Strabo (early 1st c. AD),[2] Morinos by Pomponius Mela (mid-1st c. AD) and Tacitus (early 2nd c. AD),[3] Morinō̃n (Μορινω̃ν) by Ptolemy (2nd c. AD),[4] Mōrínous (Μωρίνους; acc.) by Cassius Dio (3rd c. AD),[5] and as Morinorum (gen.) in the Notitia Dignitatum (5th c. AD).[6][7]

The Gaulish ethnonym Morini (sing. Morinos) literally means 'those of the sea', that is to say the 'sea folk' or the 'sailors'.[8] It stems from Proto-Celtic *mori ('sea'; cf. Old Irish muir, Middle Welsh mor 'sea'), itself from Proto-Indo-European *mori ('sea, standing water'; cf. Lat. mare 'sea', OHG mari 'sea, lake', Osset. mal 'standing water').[9][10]

Drawing on earlier traditions, the Morini were poetically called by Virgil the "remotest people of mankind" (extremique hominum Morini).[11][12]

Geography

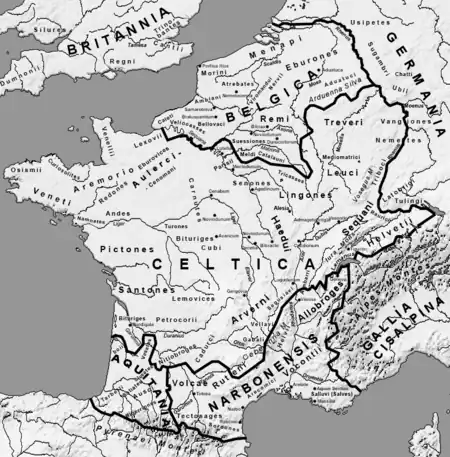

Territory

The Morini lived south of the Menapii, the river Aa bordering the two tribes from the coast to the east of Saint Omer. There, the frontier turned southwards to meet the river Leie up to Merville, at the one-time territory of the Atrebates.[13] South of their territory, they were separated from the Ambiani by the Canche river.[13]

Strabo (early 1st c. AD) describes the country of the Morini as being on the sea, close to the Menapii, and covered by part of a large forest with low thorny trees and shrubs. He also reports that before Roman conquest, the Morini and their neighbours in these forests "fixed stakes in various places, and then retreated with their whole families into the recesses of the forest, to small islands surrounded by marshes. During the rainy season these proved secure hiding-places, but in times of drought they were easily taken."[14]

Settlements

During the Roman period, their capital was known as Tervanna (or Tarvanna). The modern town of Thérouanne is located farther to the south.[15] In later imperial times, Boulogne was referred to as a civitas itself, implying either that it had supplanted Tervanna, possibly after a partial destruction in 275, or else that it had become administratively separate, perhaps because of its military and economic importance.[16]

The harbour of the Morini was named Gesoriacum from the first century BC, corresponding to present-day Boulogne-sur-Mer.[17] The settlement is almost certainly the same as Portus Itius (Latin: 'channel harbour’) mentioned by Caesar.[17] The site was mentioned as Bononia in 4 AD.[18] In fact, the denominations Gesoriacum and Bononia were used contemporaneously to designate different parts of the site. The traditional view is that Gesoriacum referred to the lower part and Bononia to the upper part of the city.[18] In late classical times, Bononia became part of the coastal defence administration known as the "Saxon shore", and was probably administered separately from Tervanna.

Culture

Caesar described the Belgae, including the Morini, as Gauls who had different language, customs and laws compared to the central part of Gaul which he called Celtic.[19] He also mentioned that he had heard that the Belgae had some Germanic ancestry from east of the Rhine.[20] Place names and personal names clearly show that the Belgae were heavily influenced by Celtic language, but some linguists such as Maurits Gysseling, have argued based on placename studies that they spoke either a Germanic language, or else another language neither Celtic nor Germanic.[21] Edith Wightman reads Caesar to make a distinction between the core of the Belgae included the Suessiones, Viromandui and Ambiani, placing the Morini, Menapii, Nervii, and other northern tribes in a "transition zone" which may have been more Germanic.[22] She proposes that coin evidence indicates that these northern tribes were probably bound to an alliance with the core group in the generations before Caesar's arrival, and that the Morini may have been a relatively new and loosely bound member of the alliance.[23]

Pliny the Elder remarked that the Morini cultivated flax and used linen to make sails.[24] The area was also known for exporting wool, geese, pork, salt, and garum.[25]

In late classical times Zosimus implied the Germanic character of the city, calling it Bononia germanorum.

History

Caesar was very interested in that part of the Morini territory, which is where the crossing of the sea to Britannia was "the shortest".[26] The Morini had several harbours of which Portus Itius, was only one.[27]

The tribe counted some pagi (subregions), which, apparently, could make their own decisions.[28] The Morini fled into or behind the marshes and became unreachable for the Roman army. In 56 BC, when autumn was very wet, this tactic worked. The year after, which was much dryer, it failed.[29] The Morini participated together with other coastal people (Lexovii, Namnetes, Ambiliati, Diablintes and Menapii) and tribes from Britain, in the uprising of the Veneti.[30]

Caesar wanted to induce fear in the northern Morini so "that they wouldn't attack him."[31] The territory of the Morini and Menapii was well protected by marshes and woodland and suited for guerrilla tactics. The dangers outweighed the benefits of subduing those economically less interesting regions. In 55 BC Labienus tightened the Roman grip upon the strategically more important western side of the Morini tribal areas.[32] In 54 BC Caesar let one legion, under the command of legate Caius Fabius, hibernate there.[33] In 53 BC the Morini were joined most probably with the Menapii under the command of the Atrebate Commius.[34] During the great Gallic rebellion led by Vercingetorix, the Morini, like many other Gaulish tribes, sent a contingent of some 5000 men to the relief force which had to liberate Alesia.[35]

Although Caesar fought the Morini, he managed to conquer only a part of their territory around Calais. The rest of the Morini were annexed by emperor Augustus between the years 33-23 B.C. Their tribal lands became part of the Roman province of Gallia Belgica, forming one district together with the Atrebates and Ambiani.[36]

The area was converted to Christianity by Saints Victoricus and Fuscian, but the region was re-evangelized by Saint Omer in the seventh century. Thérouanne became the capital of a medieval diocese which included the old territories of the Morini and Atrebates, as well as part of the old Menapian civitas.

See also

References

- Caesar. Commentarii de Bello Gallico, 2:4, passim; Pliny. Naturalis Historia, 4:106.

- Strabo. Geōgraphiká, 4:3:5.

- Pomponius Mela. De situ orbis, 3:3:23; Tacitus. Historiae, 4:28.

- Ptolemy. Geōgraphikḕ Hyphḗgēsis, 2:9:1.

- Cassius Dio. Rhōmaïkḕ Historía, 39:44.

- Notitia Dignitatum, 40:52.

- Falileyev 2010, s.v. Morini.

- Lambert 1994, p. 34; Delamarre 2003, p. 229; Busse 2006, p. 199; Matasović 2009, p. 277.

- Delamarre 2003, p. 229.

- Matasović 2009, p. 277.

- Wightman 1985, p. 29.

- Fratantuono & Smith 2018, p. 743.

- Schön, Franz (2006). "Morini". Brill's New Pauly. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e809950.

- Geographica IV 3

- Schön, Franz (2006). "Tervanna". Brill's New Pauly. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e1205060.

- Wightman 1985, p. 204.

- Stevens & Drinkwater 2015.

- Schön, Franz (2006). "Gesoriacum". Brill's New Pauly. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e423500.

- Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico 1.1

- Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico 2.4

- See Belgae.

- Wightman 1985, p. 12.

- Wightman 1985, pp. 20 & 29.

- Natural History XIX.2

- G. P. A. Besuijen, Rodanum: A Study of the Roman Settlement at Aardenburg and Its Metal Finds page 11 and page 33

- Caes., D.B.G., IV 21.3 - previously, Caesar knew only the crossing from the Veneti region

- Caes., D.B.G., V 2.3; Strabo, Geographia IV 5.2.

- Caes., D.B.G., IV 22.1, 5.

- Caes., D.B.G., III 28-29; IV 38. In book III Caesar writes about "uninterrupted woodlands and marshes". In Book IV he notes that the Morini had withdrawn in the marshes and the Menapii in the woods (IV 38.2-3).

- Caes., D.B.G., III 9.10

- Caes., D.B.G., IV 22

- Caes., D.B.G., IV 38.1-2

- Caes., D.B.G., V 24.2

- Caes., D.B.G., VI 8.4 en VII 76.2

- Caes., D.B.G., VII 75.3

- Wightman 1985, p. 63.

Bibliography

- Busse, Peter E. (2006). "Belgae". In Koch, John T. (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 195–200. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental. Errance. ISBN 9782877723695.

- Falileyev, Alexander (2010). Dictionary of Continental Celtic Place-names: A Celtic Companion to the Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. CMCS. ISBN 978-0955718236.

- Fratantuono, Lee M.; Smith, R. Alden (2018). Virgil, Aeneid 8: Text, Translation, and Commentary. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-36738-8.

- Lambert, Pierre-Yves (1994). La langue gauloise: description linguistique, commentaire d'inscriptions choisies. Errance. ISBN 978-2-87772-089-2.

- Matasović, Ranko (2009). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic. Brill. ISBN 9789004173361.

- Nègre, Ernest (1990). Toponymie générale de la France. Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-02883-7.

- Stevens, Courtenay E.; Drinkwater, John F. (2015), "Gesoriacum", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.2834, ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5

- Wightman, Edith M. (1985). Gallia Belgica. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05297-0.