Bructeri

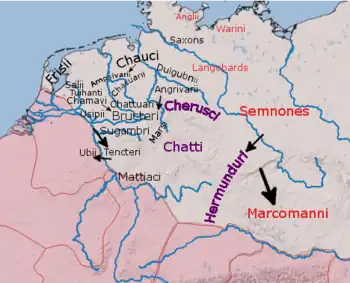

The Bructeri (from Latin; Greek: Βρούκτεροι, Broukteroi, or Βουσάκτεροι, Bousakteroi; Old English: Boruhtware) were a Germanic tribe[1] in Roman imperial times, located in northwestern Germany, in present-day North Rhine-Westphalia. Their territory included both sides of the upper Ems (Latin Amisia) and Lippe (Latin Luppia) rivers. At its greatest extent, their territory apparently stretched between the vicinities of the Rhine in the west and the Teutoburg Forest and Weser river in the east. In late Roman times they moved south to settle upon the east bank of the Rhine facing Cologne, an area later associated with the Ripuarian Franks.

Role in history

The Bructeri formed an alliance with the Cherusci, the Marsi, the Chatti, Sicambri, and the Chauci, under the leadership of Arminius, that defeated the Roman General Varus and annihilated his three legions at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD.

Six years later, one of the generals serving under Germanicus, Lucius Stertinius defeated the Bructeri near the Ems and devastated their lands. Among the booty captured by Stertinius was the eagle standard of Legio XIX that had been lost at Teutoburg Forest. "The troops were then marched to the furthest frontier of the Bructeri, and all the country between the rivers Amisia and Luppia was ravaged, not far from the forest of Teutoburgium, where the remains of Varus and his legions were said to lie unburied."[2] Scholars consider the Bructeri among the most dangerous Germanic enemies of Rome.[3]

The Bructeri in 69-70 participated in the Batavian rebellion. The best known of the Bructeri was their wise virgin Veleda, the spiritual leader of the Batavi rising, regarded as a goddess.[4] She foretold the success of the Germans against the Roman legions during the Batavian revolt. A Roman Munius Lupercus was sent to offer her gifts but was murdered on the road.[5] The inhabitants of Cologne, the Ubii, asked for her as an arbiter; "they were not, however, allowed to approach or address Veleda herself. In order to inspire them with more respect they were prevented from seeing her. She dwelt in a lofty tower, and one of her relatives, chosen for the purpose, conveyed, like the messenger of a divinity, the questions and answers."[6]

In his Germania, Tacitus reported that the Chamavi and Angrivarii had moved to the territories of the Bructeri, after having driven them out and totally annihilated them, in alliance with other nearby populations, whom the Latin writer thanks for "offering delight to Roman eyes", without Rome having to intervene. More than 60,000 of the Bructeri fell.

"May the tribes, I pray, ever retain if not love for us [Romans], at least hatred for each other; for while [...], fortune can give no greater boon than discord among our foes."[7]

Geography

The Bructeri were sometimes divided into major and minor divisions. Strabo (64/63 BC – c. 24 AD) describes the Lippe river running through the territory of the lesser Bructeri (Βουσάκτεροι), about 600 stadia from the Rhine.[8] Ptolemy (c. AD 90 – c. AD 168) says that lesser Bructeri and the Sicambri occupied the area just to the north of the Rhine. Both authors agree that the greater Bructeri in their time lived between the Ems and the Weser, to the south of a part of the Chauci.[9] Tacitus (56 AD – 117 AD) on the other hand, states that the Bructeri had been forced from their territory, which he describes as having been north of the Tencteri who were on the Rhine at the time, between Cologne and the Chatti. This was done by the Chamavi and Angrivarii, who neighbored the Bructeri upon their north, along with other neighboring tribes. More than sixty thousand fell in this conflict, which the Romans had been able to observe with satisfaction.[10] Pliny the Younger (died 113) mentioned in a letter (2.7) that in his time "a triumphal Statue was decreed by the Senate to Vestricius Spurinna", at the Motion of the Emperor, because he "had brought the King of the Bructeri into his Realm by force of War; and even subdu'd that rugged Nation, by the Sight and Terror of it, the most honourable kind of Victory".

Later history

The Bructeri eventually disappear from historical records, apparently absorbed into the Frankish communities of the early Middle Ages. The final mentions of their name seem to indicate this, and also that they had moved south from their old position north of the Lippe.

In 307–308, after having spent the year before fighting Franci raiding along the Rhine and the executions of instigators Ascaric and Merogais, emperor Constantine led a punitive expedition against the Bructeri over the Rhine and built a bridge at Cologne.

In 392 AD, according to a citation by Gregory of Tours, Sulpicius Alexander reported that Arbogast crossed the Rhine to punish the Franks for incursions into Gaul. He first devastated the territory of the Bricteri, near the bank of the Rhine, then the Chamavi, apparently their neighbours. Both tribes did not confront him. The Ampsivarii and the Chatti however were under military leadership of the Frankish princes Marcomer and Sunno and they appeared "on the ridges of distant hills". At this time the Bructeri apparently lived near Cologne. (Note that the Chamavi and the Ampsivarii are the two peoples that Tacitus had long before noted as having conquered the Bructeri from their north.)

In the Peutinger map, the Bructeri also appear as a distinct entity on the opposite side of the Rhine to Cologne and Bonn, the Burcturi, with Franks to their north, and Suevi to their south. This has been interpreted to mean that the Bructeri had moved into the area previously inhabited by the Tencteri and Usipetes, which had in the time of Caesar been inhabited by the Ubii (who had in turn crossed the Rhine to inhabit Cologne as Roman citizens during imperial times). In the description of Claudius Ptolemy, the Bructeri and Sicambri are apparently close to their old positions, but with Suevi having inserted themselves upon the Rhine and the Tencteri and Usipetes much further south, near the Black Forest. This document is however suspected of resulting from confused use of primary sources.[11]

Sidonius Apollinaris, in his Poems, VII, lists the Bructeri among the allies who crossed the Rhine into Gaul under Attila in 451, leading to the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields. (After them are listed the Franks living along the Neckar River.) But it is possible, according for example to E. A. Thompson that Sidonius included names of historical tribes, for effect.

The name of the Arboruchoi (Αρβόρυχοι), a people described by Procopius (550s) as living next to the Franks along the lower Rhine during the time of Clovis I (c. 490), may be identical with that of the Bructeri. According to Procopius, they were Roman foederati who warred with the Franks before joining and merging with them, although they retained some of the customs from their Roman service down to Procopius' time. Not all scholars accept their identification with the Bructeri, however, which depends on a misspelling by Procopius (Arboruchoi for Arboruchtoi).[12]

By 690 Bructeri were found in Thuringia, after the Saxons had conquered their homeland; their name is preserved in the names Großbrüchter and Kleinbrüchter, in the municipality Helbedündorf.[13] Under the Carolingians the name of the Bructeri was still being used for a gau in the region near where they had originally lived, the so-called Brukterergau (or Borahtra, Botheresgau, Botheresge, Pagus Boroctra). This was however now south of the Lippe, and north of the Ruhr river, in the area classically inhabited by the Sicambri. This area is today the well-known and heavily populated Ruhr region of Germany.[14]

At the beginning of the eighth century, Bede in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People lists among the peoples "from whom the Angles and Saxons who now live in Britain derive their origin" the Boruhtware (original Latin Bede Boructuari, Old English Bede Boructuare). In the same passage Bede also lists the Frisians, Rugians, Danes, Huns and continental Saxons. This name is usually identified with that of the Bructeri.[15] According to Walter Pohl, the mention of the Bructeri (or Boructuarii, as he calls them) may be a classical allusion designed to establish continuity between the barbarian present and past.[16] Ian Wood, noting that the Bricteri of Gregory of Tours are usually considered either a Saxon or Frankish group, suggests that the Boructuarii represent the Frankish component in the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain.[17]

Literature

- Ralf G. Jahn: Der römisch-germanische Krieg (9-16 n. Chr.). Inaugural-Dissertation, Bonn 2001.

- Günter Neumann, Harald von Petrikovits, Rafael von Uslar: Brukterer. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Bd. 3, S. 581ff.

References

-

- Wells, Peter S. (2018). "Bructeri". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191744457. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

Bructeri. A Germanic people who lived near the Ems River in northern Germany.

- Thompson, Edward Arthur; Drinkwater, John Frederick (2012). "Bructeri". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (4 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191735257. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

Bructeri, a Germanic people living north of the Lippe in the neighbourhood of modern Münster. A powerful people...

- Wells, Peter S. (2018). "Bructeri". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191744457. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- Tac. Ann. 1.60

- Brukterer, § 2 (Historisches). In: Germanische Altertumskunde Online. Vol. 3 (1978), S. 585.

- Tac. Ger. 8

- Tac. Hist. 4.61

- Tac. Hist. 4.65

- Tac. Ger. 33

- Strabo, Geography 7.1

- Ptolemaeus 2.11. and also at lacuscurtius site

- Tac. Ger. 33

- Schütte, Ptolemy's maps of northern Europe, a reconstruction of the prototypes

- Jean-Pierre Poly (2016), "Freedom, Warriors' Bond, Legal Book: The Lex Salica Between Barbarian Custom and Roman Law", Clio et Thémis, 11: 1–25, at 10.

- Schimpff, Volker (2007). "Sondershausen und das Wippergebiet im früheren Mittelalter - einige zumeist namenkundliche Bemerkungen eines Archäologen". Alt-Thüringen (in German). 40: 291–302.

- Zeuss, Die Deutschen und die Nachbarstämme

- Windy A. McKinney (2011), Creating a gens Anglorum: Social and Ethnic Identity in Anglo-Saxon England through the Lens of Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica (PDF) (PhD diss.), University of York, pp. 10 & 135.

- Walter Pohl (1997), "Ethnic Names and Identities in the British Isles: A Comparative Perspective", in John Hines (ed.), The Anglo-Saxons from the Migration Period to the Eighth Century: An Ethnographic Perspective, Boydell Press, pp. 7–32, at 15.

- Ian N. Wood (1997), "Before and After the Migration to Britain", in John Hines (ed.), The Anglo-Saxons from the Migration Period to the Eighth Century: An Ethnographic Perspective, Boydell Press, pp. 41–53, at 41 & 44.

External links

- Legio XIX, www.livius.org „In 15, the eagle of the nineteenth was recovered by the Roman commander Lucius Stertinius among the Bructeri.“