Geography of California

California is a U.S. state on the western coast of North America. Covering an area of 163,696 sq mi (423,970 km2), California is among the most geographically diverse states. The Sierra Nevada, the fertile farmlands of the Central Valley, and the arid Mojave Desert of the south are some of the major geographic features of this U.S. state. It is home to some of the world's most exceptional trees: the tallest (coast redwood), most massive (Giant Sequoia), and oldest (bristlecone pine). It is also home to both the highest (Mount Whitney) and lowest (Death Valley) points in the 48 contiguous states. The state is generally divided into Northern and Southern California, although the boundary between the two is not well defined. San Francisco is decidedly a Northern California city and Los Angeles likewise a Southern California one, but areas in between do not often share their confidence in geographic identity. The US Geological Survey defines the geographic center of the state at a point near North Fork, California.

Earth scientists typically divide the state into eleven distinct geomorphic provinces with clearly defined boundaries. They are, from north to south, the Klamath Mountains, the Cascade Range, the Modoc Plateau, the Basin and Range, the Coast Ranges, the Central Valley, the Sierra Nevada, the Transverse Ranges, the Mojave Desert, the Peninsular Ranges, and the Colorado Desert.

State boundaries

The boundaries of California were defined by Spanish claims of Mexico, as part of the province of Alta California. The northern boundary of Spanish claims was set at 42 degrees latitude by the Adams–Onis Treaty of 1819.[1] The states of Nevada and Utah, also originally part of Alta California, also use that line for their northern boundaries. The southern boundary, between California and Mexico, was established by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican–American War in 1848. The line is about 30 miles north of the former Alta California southern boundary. The eastern boundary consists of two straight lines: a north–south line from the northern border to the middle of Lake Tahoe, and a second line angling southeast to the Colorado River. From that point, 14 mi (23 km) south-southwest of Davis Dam on Lake Mohave, the southeast boundary follows the Colorado River to the international border west of Yuma. The eastern and south-eastern boundaries were decided upon during the debates of the California Constitutional Convention in 1849.

Northern California

Northern California usually refers to the state's northernmost 48 counties.

The main population centers of Northern California include San Francisco Bay Area (which includes the cities of San Francisco, Oakland, and the largest city of the region, San Jose), and Sacramento (the state capital) as well as its metropolitan area. It also contains redwood forests, along with the Sierra Nevada including Yosemite Valley and Lake Tahoe, Mount Shasta (the second-highest peak in the Cascade Range after Mount Rainier in Washington), and the northern half of the Central Valley, one of the world's most productive agricultural regions. The climate can be generally characterized by its marine to warm Mediterranean climates along the coast, to somewhat Continental Mediterranean Climate in the valley to alpine climate zones in the high mountains. Apart from the San Francisco Bay Area and Sacramento metropolitan areas (and some other cities in the Central Valley), it is a region of relatively low population density. Northern California's economy is noted for being the de facto world leader in industries such as high technology (both software and semiconductor), as well as being known for clean power, biomedical, government, and finance.

.jpg.webp)

Klamath Mountains

The Klamath Mountains are a range in northwest California and southwest Oregon, the highest peak being Mount Eddy in Trinity County, California, at 9,037 feet (2,754 m).[2] The range has a varied geology, with substantial areas of serpentine and marble. The climate is characterized by moderately cold winters with heavy snowfall and warm, very dry summers with limited rainfall.[3] As a consequence of the geology, the mountains have a unique flora, including several endemic or near-endemic species, such as Lawson's Cypress (Chamaecyparis lawsoniana) and Foxtail Pine (Pinus balfouriana). Brewer's Spruce (Picea breweriana) and Kalmiopsis (Kalmiopsis leachiana) are relict species, remaining since the last ice age.[4]

Cascade Range

The Cascade Range is a mountainous region stretching from the Fraser River in British Columbia, Canada down to south of Lassen Peak, California.[5] The Cascades (as they are called for short) are part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, the ring of volcanoes around the Pacific Ocean.[6] All of the known historic eruptions in the contiguous United States have been from either Cascade volcanoes or near Mono Lake.[7]: 7 Lassen Peak was the last Cascade volcano to erupt in California, from 1914 to 1921. Lassen is the most southerly active volcano of the Cascade chain.[8]

This region is located in the northeastern section of the state bordering Oregon and Nevada, mostly north of the Central Valley and the Sierra Nevada mountain range. The area is centered on Mount Shasta, near the Trinity Alps. Mount Shasta is a dormant volcano, but there is some evidence that it erupted in the 18th century.[7]: 99

Modoc Plateau

In the northeast corner of the state lies the Modoc Plateau, an expanse of lava flows that formed a million years ago and now lie at an altitude of 4,000 to 5,000 feet (1,200 to 1,500 m).[9] The plateau has many cinder cones, juniper flats, pine forests, and seasonal lakes.[10] The plateau lies between the Cascade Range to the west and the Warner Mountains to the east.[9] The Lost River watershed drains the north part of the plateau, while southern watersheds either collect in basin reservoirs or flow into Big Sage Reservoir and thence to the Pit River.

Nine percent of the plateau is protected as reserves or wilderness areas,[9] such as the Modoc National Wildlife Refuge.[11] The plateau supports large herds of mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), Rocky Mountain Elk (Cervus canadensis), and pronghorn (Antilocapra americana).[9] Herds of wild horses and livestock grazing have altered the original high desert ecosystem of the plateau.[9]

.jpg.webp)

Basin and Range

To the east of the Sierra is the Basin and Range geological province, which extends into Nevada. The Basin and Range is a series of mountains and valleys (specifically horsts and grabens), caused by the extension of the Earth's crust.[12] One notable feature of the Basin and Range is Mono Lake, which is the oldest lake in North America.[13] The Basin and Range also contains the Owens Valley, the deepest valley in North America (more than 10,000 feet (3 km) deep, as measured from the top of Mount Whitney).[14]

In the eastern part of the state, below the Sierra Nevada, there is a series of dry lake beds that were filled with water during the last ice age (fed by ice melt from alpine glaciers but never directly affected by glaciation; see pluvial).[15] Many of these lakes have extensive evaporite deposits that contain a variety of different salts. In fact, the salt sediments of many of these lake beds have been mined for many years for various salts, most notably borax (this is most famously true for Owens Lake and Death Valley).

In this province reside the White Mountains, which are home to the oldest living organism in the world, the bristlecone pine[16]

Coast Ranges

To the west of the Central Valley lies the Coast Ranges, including the Diablo Range, just east of San Francisco, and the Santa Cruz Mountains, to the south of San Francisco. The Coast Ranges north of San Francisco become increasingly foggy and rainy. These mountains are noted for their coast redwoods, the tallest trees on earth, which live within the range of the coastal fog.

Central Valley

California's geography is largely defined by its central feature—the Central Valley, a huge, fertile valley between the coastal mountain ranges and the Sierra Nevada. The northern part of the Central Valley is called the Sacramento Valley, after its main river, and the southern part is called the San Joaquin Valley /ˌsæn wɑːˈkiːn/, after its main river. The whole Central Valley is watered by mountain-fed rivers (notably the San Joaquin, Kings, and Sacramento) that drain to the San Francisco Bay system. The rivers are sufficiently large and deep that several inland cities, notably Stockton, and Sacramento are seaports.

The southern tip of the valley has interior drainage and thus is not technically part of the valley at all. Tulare Lake, once 570 square miles (1,476 square kilometers) and was dry until the winter of 2022 and early spring of 2023, and partially covered with agricultural fields, once filled much of the area.

Sierra Nevada

In the east of the state lies the Sierra Nevada, which runs north–south for 400 miles (640 km). The highest peak in the contiguous United States, Mount Whitney at 14,505 feet (4.42 km), lies within the Sierra Nevada. The topography of the Sierra is shaped by uplift and glacial action.

The Sierra has 200–250 sunny days each year, warm summers, fierce winters, and varied terrain, a rare combination of rugged variety and pleasant weather. The famous Yosemite Valley lies in the Central Sierra. The large, deep freshwater Lake Tahoe lies to the North of Yosemite. The Sierra is also home to the Giant Sequoia, the most massive trees on Earth.

The most famous hiking and horse-packing trail in the Sierra is the John Muir Trail, which goes from the top of Mt. Whitney to Yosemite valley. This is part of the Pacific Crest Trail that goes from Mexico to Canada. The three major national parks in this province are Yosemite National Park, Kings Canyon National Park, and Sequoia National Park.

Southern California

The term Southern California usually refers to the ten southernmost counties which closely match the lower one-third of California's span of latitude. This definition coincides neatly with the county lines at 35° 47′ 28″ north latitude, which form the northern borders of San Luis Obispo, Kern, and San Bernardino counties. Another definition for Southern California uses the Tehachapi Mountains as geographic landmarks for the northern boundary.

Southern California consists of a heavily developed urban environment, home to some of the largest urban areas in the state, along with vast areas that have been left undeveloped. With over 22 million people, roughly 60% of California's population resides in Southern California. It is the second-largest urbanized region in the United States, second only to the Washington/Philadelphia/New York/Boston Northeastern Megalopolis. Where these cities are dense, with major downtown populations and significant rail and transit systems, much of Southern California is famous for its large, spread-out, suburban communities and use of automobiles and highways. The dominant areas are Los Angeles, Orange County, San Diego, and Riverside-San Bernardino, each of which is the center of its respective metropolitan area, composed of numerous smaller cities and communities. The urban area is also host to an international metropolitan region in the form of San Diego–Tijuana, created by the urban area spilling over into Baja California.

Southern California is noted for industries including the film industry, residential construction, entertainment industry, and military aerospace. Other industries include software, automotive, ports, finance, tourism, biomedical, and regional logistics.

Transverse Ranges

Southern California is separated from the rest of the state by the east–west trending Transverse Ranges, including the Tehachapi, which separate the Central Valley from the Mojave Desert. Urban Southern California intersperses the valleys between the Santa Susana Mountains, Santa Monica Mountains and San Gabriel Mountains, which range from the Pacific Coast, eastward over 100 miles (160 km), to the San Bernardino Mountains, north of San Bernardino. The highest point of the range is Mount San Gorgonio at 11,499 feet (3,505 m). The San Gabriel Mountains have Mount Wilson observatory, where the redshift was discovered in the 1920s.

The Transverse Ranges include a series of east–west trending mountain ranges that extend from Point Conception at the western tip of Santa Barbara County, eastward (and a bit south) to the east end of the San Jacinto Mountains in western Riverside County. The Santa Ynez Mountains make up the westernmost ranges, extending from Point Conception to the Ventura River just west-northwest of Ojai, in Ventura County. Pine Mountain Ridge, Nordhoff Ridge–Topatopa Mountains, Rincon Peak–Red Mountain, Sulphur Mountain, Santa Paula Ridge, South Mountain–Oat Mountain–Santa Susana Mountains, Simi Hills, Conejo Mountains–Santa Monica Mountains are all part of the Western Transverse Ranges, in Ventura and western Los Angeles counties.

The Liebre Mountains occupy the northwest corner of Los Angeles County, and represent a northwestern extension of the San Gabriel Mountains, both on the Pacific Plate side of the San Andreas Fault. The fault divides the San Gabriel Mountains from the San Bernardino Mountains further to the east in San Bernardino County.

It is possible to surf in the Pacific Ocean and ski on a mountain during the same winter day in Southern California.

Mojave Desert

There are harsh deserts in the Southeast of California. These deserts are caused by a combination of the cold offshore current, which limits evaporation, and the rain shadow of the mountains. The prevailing winds blow from the ocean inland. When the air passes over the mountains, adiabatic cooling causes most water in the air to rain on the mountains. When the air returns to sea level on the other side of the mountains, it recompresses, warms and dries, parching the deserts. When the wind blows from inland, the resulting hot dry katabatic winds are called the Santa Ana Winds.

The Mojave Desert is bounded by the peninsular Tehachapi Mountains on the Northwest, together with the San Gabriel and the San Bernardino Mountains on the Southwest. These Western boundaries are quite distinct, forming the dominant pie-slice shaped Antelope Valley in Southern California. The outlines of this valley are caused by the two largest faults in California: the San Andreas and the Garlock. The Mojave Desert extends Eastward into the State of Nevada. The Mojave Desert receives less than 6 inches (150 mm) of rain a year and is generally between 3,000 and 6,000 feet (1,000 and 2,000 m) of elevation. Areas such as the Antelope Valley desert which is a high desert received snow each year, in the past it could snow 2–3 times a year; however, recently snow level has declined significantly to once a year or less. Most of the towns and cities in the California portion of the Mojave are relatively small, except for Palmdale and Lancaster. However, some are quite famous like Barstow, a popular stop on the famous U.S. Route 66. The Mojave Desert also contains the lowest, hottest place in the Americas: Death Valley, where temperature normally approaches 120 °F (49 °C), in late July and early August.

Peninsular Ranges

The southernmost mountains of California are the Peninsular Ranges, which are east of San Diego and continue into Baja California (Mexico) in the Sierra San Pedro Martir. The Peninsular Ranges contain the Laguna Mountains, the San Jacinto Mountains, the Santa Rosa Mountains, the Santa Ana Mountains and the Palomar Mountain Range, notable for its famous Palomar observatory. San Jacinto Peak's eastern shoulder has a cable tram that runs from the desert floor to nearly the top of the mountain where riders can set off hiking or go cross-country skiing.

Colorado Desert

To the east of the peninsular ranges lie the Colorado and Sonoran Deserts, which extend into Arizona and Mexico.

The ground elevation is generally lower and in some areas was compressed downward, therefore the eastern Coachella and Imperial Valleys north of the U.S.-Mexican border are below sea level. The lowest community in the U.S. is Calipatria, California, at 180 feet (55 m) below sea level.[17]

One feature of the desert is the Salton Sea, an inland lake that was formed in 1905 when a swollen Colorado River breached a canal near the U.S.-Mexico border and flowed into the Salton Sink (Salton Basin) for almost two years. Today, the Salton Sea, a new version of historic Lake Cahuilla, remains as California's largest lake.

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean lies to the west of California. Owing to the long length of the state, Sea temperatures generally range from 50 °F (10 °C) in the northernmost parts during winter to 70 °F (21 °C) in the south coast during summer. The lower seasonal temperature variance compared to the waters of the East Coast is because of up-welling deep waters with dissolved nutrients. Therefore, sea life in and around California has examples of both Arctic and tropical, biotopes, leaning more towards the latter in the south coast and vice versa. The sea off California is remarkably fertile, a murky green filled with a massive variety of fish, rather than the clear dead blue of most tropical seas. Before 1930, there was an extremely valuable sardine (herring) fishery off Monterey, but this was depleted, an event later famous as the background to John Steinbeck's Cannery Row.

California's coastline is about 840 miles long, the third longest coastline in the United States after Alaska and Florida.

Geology

Faults, volcanoes, and tsunamis

Earthquakes occur due to faults that run the length of the Pacific coast, the largest being the San Andreas Fault. Major historical earthquakes include, with the magnitudes listed:

- 1906 San Francisco earthquake (magnitude 7.8–8.2)

- 1971 San Fernando earthquake (magnitude 6.6)

- 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake (magnitude 6.9–7.1)

- 1994 Northridge earthquake (magnitude 6.7)

Coastal cities are vulnerable to tsunamis from locally generated earthquakes as well as those elsewhere in the Pacific Ring of Fire. The Great Chilean earthquake tsunami (1960) killed one person and caused $500,000 to $1,000,000 dollars of damage in Los Angeles, damaged harbors in many coastal cities, and flooded streets in Crescent City.[18] Waves from the Alaskan Good Friday earthquake of 1964 killed twelve people in Crescent City and caused damage as far south as Los Angeles. USGS has released the UCERF California earthquake forecast which models earthquake occurrence in California.

California is also home to several volcanoes, including Lassen Peak, which erupted in 1914 and 1921, and Mount Shasta.

Tectonics

California, when only partially explored by the Spanish, was once thought to be an island, as when the southern Baja California Peninsula is approached from the Gulf of California the land appears to the west. It is expected, through the motions of plate tectonics that the sea floor spreading now acting in the Gulf of California (also known as the Sea of Cortez) will eventually extend through Southern California and along the San Andreas fault to below San Francisco, finally forming a long island in less than 150 million years. (For comparison, this is also the approximate age of the Atlantic Ocean.) Predictions suggest that this island will eventually collide with Alaska after an additional 100 million years.

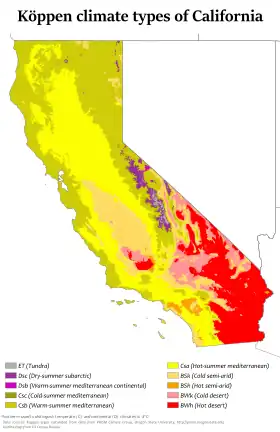

Climate

California's climate varies widely, from arid to subarctic, depending on latitude, elevation, and proximity to the coast. Coastal and Southern parts of the state have a Subtropical Mediterranean climate, with somewhat rainy winters and dry summers. The influence of the ocean generally moderates temperature extremes, creating warmer winters and substantially cooler summers, especially along the coastal areas.

The state is subject to coastal storms during the winter. Eastern California is subject to summertime thunderstorms caused by the North American monsoon. Dry weather during the rest of the year produces conditions favorable to wildfires. California hurricanes occur less frequently than their counterparts on the Atlantic Ocean. Higher elevations experience snowstorms in the winter months.

Floods are occasionally caused by heavy rain, storms, and snowmelt. Steep slopes and unstable soil make certain locations vulnerable to landslides in wet weather or during earthquakes.

See also

- Deserts of California

- Ecology of California

- List of California 14,000-foot summits

- List of California state parks

- List of forts in California

- List of lakes in California

- List of mountain peaks of California

- List of mountain ranges of California

- List of regions of California

- List of rivers of California

- List of the major 3000-meter summits of California

- List of islands of California

- List of lakes of California

- List of beaches in California

References

- Barnard, Jeff (May 19, 1985). "California–Oregon Dispute : Border Fight Has Townfolk on Edge". Los Angeles Times.

- "Klamath Mountains". Peakbagger. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- Skinner, C.N.; Taylor, A.H.; Agee, J.K. (2006). "Klamath Mountains bioregion". In Sugihara, N.G.; van Wagtendonk, J.W.; Fites-Kaufman, J.; Shaffer, K.E.; Thode, A.E. (eds.). Fire in California's Ecosystems. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 170–194.

- "KLAMATH-SISKIYOU REGION, California and Oregon, U.S.A." North America Regional Centre of Endemism. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2011-11-26.

- Beckey, Fred W. (2000). Cascade Alpine Guide: Columbia River to Stevens Pass. Mountaineers Press. p. 11.

- Singh, Pratap; Haritashya, Umesh Kumar (2011). Encyclopedia of Snow, Ice and Glaciers. Springer. p. 111.

- Harris, Stephen L. (2005). Fire Mountains of the West: The Cascade and Mono Lake Volcanoes (3rd ed.). Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87842-220-3.

- "Eruptions of Lassen Peak". USGS. Fact Sheet 173-98. Retrieved 2011-11-26.

- "Modoc Plateau Region" (PDF). California Wildlife Action Plan. California Department of Fish and Game. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-02.

- Sugihara, Neil G. (2006). Fire in California's ecosystems. University of California Press. p. 225.

- "Modoc National Wildlife Refuge". US Fish and Wildlife Service.

- "Basin and Range Province". USGS Geology in the Parks. USGS. Archived from the original on 2009-01-25. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- Harris, S.L. (2005). Fire Mountains of the West: The Cascade and Mono Lake Volcanoes. Mountain Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-87842-511-2.

- Smith, Genny; Putnam, Jeff (1976). Deepest Valley: a Guide to Owens Valley, its roadsides and mountain trails (2nd ed.). Genny Smith books. ISBN 0-931378-14-1.

- US Geological Survey (30 June 2000). "Shoreline Butte: Ice age Death Valley". Death Valley Geology Field Trip Shoreline Butte. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- Bain, G. Donald (2001). "Explore the Methuselah Grove". NOVA Online: Methuselah Tree. PBS.

- "Geographic Names Information System".

- May 22, 1960 Tsunami

Further reading

- Miller, Crane S., and Richard S. Hyslop. California, the Geography of Diversity (Mayfield Publishing Company, 1983).

- Pyne, Stephen J. California: A Fire Survey (2016) online

- Safford, Hugh D., et al. "Fire ecology of the North American Mediterranean-climate zone." in Fire ecology and management: Past, present, and future of US forested ecosystems (2021): 337-392. re California and its neighbors online

- Selby, William A. Rediscovering the Golden State: California Geography (John Wiley & Sons, 2018). online