Garre

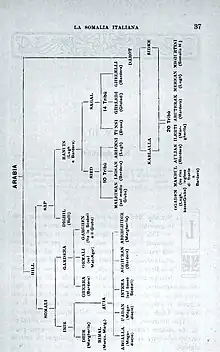

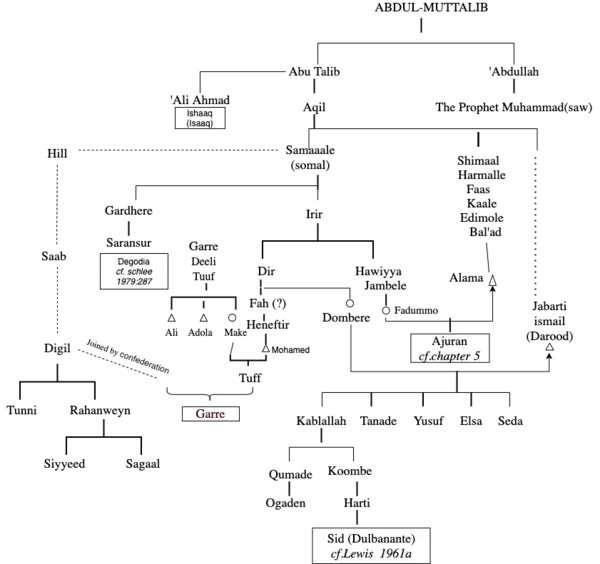

The Garre (also Gurreh, Karre, or Binukaaf, Somali: Reer Garre, Arabic: بنو كاف, romanized: Banī kāf) are a prominent Somali clan that traces its lineage back to Samaale, who is believed to have originated from the Arabian Peninsula through Aqiil Abu Talib.[1][2] The Garre clan is considered to be a sub-clan of the Digil-Rahanweynl[3] clan family, which is part of the larger Rahanweyn clan. However, genealogically, they are descended from Gardheere Samaale.[4] The Garre are also categorized as southern Hawiye as well.[5][6]

| Garre بنو كاف | |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Somali |

| Nisba | Garrow |

| Location | Somalia, Ethiopia, Kenya |

| Descended from | Gardheere |

| Parent tribe | Samaale |

| Branches |

|

| Language | Somali, Garre |

| Religion | Islam |

Overview

Somali | |

|---|---|

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Hawiye, Dir, and Rahanweyn |

Garre are also classified into three major entities of the same lineage but greatly recognized for their unique linguistics characteristics which are widely believed to have developed after their wide dispersal around the Horn of Africa, Garre Libin are identified by their language which resembles Oromo whom it is believed they had a long time interaction as nomadic in southern Ethiopia and Northern Kenya. Garre Marre are found around the major Ganale Doria and Dawa basins in Southern Ethiopia and are identified by their unique dialect derived from the Rahanweyn (Digil and Mirifle) communities whom they interacted and settled with in parmanent agrarian settlements along Ganale Doria and River Jubba.The third component of Garre which is believed to be the bearers of the original Garre language are identified as Garre Konfuur due to their dominant settlement in South Central Somalia.

The Garre Somalis colonised the Barava-Bajun region, the NFD of Kenya, and Bale province in Ethiopia before the Boorana and Warday Oromo.[7] Garre also founded cities like Barawe,[8][9] and Kismaayo

Etymology

The Garre are ancient Somali group that predated Hawiye. Garre, the word Gar is derived from the soomali language, it means the strong rope that is used to tie a camel and used for transporting,[10] i.e the camel train. Gar, "Garrow" means also in the somali language bearded man. Gar means Just(Fairness) in the Maay dialect[11] which is one of the oldest Somali language. It also means "my home" in Harla language.

Genetics

According to Cruciani et al. (2007) and the Y-DNA analysis by Hirbo, around 75% of Garre carry the paternal E-M78 E-V-12 haplogroup, which likely originated in Northern Africa. The garre are the highest carriers of the haplo-group E-V12.[12] This genetically proves that Garre are one of the ancient and the oldest Somali clan. For instance, the TMRCA of Harti is 800yrs, the Hawiye are 2100-3100yrs but the Garre are 4500yrs. They are classified as Proto-Somali. The haplogroup E-m78 EV12*[13] is progenitors of E-v32 which is highest frequencies in Somalis and Borana and Ev-22 which is Saho and Afar.

History

Introduction

The Garre are of Somali[2][14] origin being descendants of Samaale[1][2] tracing their lineage to Garedheere,[1] sons of Samaale.[15] the Garre are divided into two major clans, Garre-Tuuf who are associated with the 'Pre-Hawiye' group (Gardhere - Saransoor- Yahabur - Mayle)[16] and Quranyow who claim to descend from Dir clan, sub-clans of Mohamed Xinifitire -Maher Dir-.[17][18][19] The Garre joined Rahanweyn constituent sub-clans of Digil, forming a part of the Rahanweyn confederation of clans,[2][20] this was due to the fruit of nomadic life, the necessity of defense, the movement of new territory necessitated by a constant search for pasture and water have resulted over formation of new alliances and later, new clan identities. This show's indeed the Somali saying "tol waa tolane'' (clan is something joined together) and the structure is not based on blood relationship, that is why you will find Garre is closely affiliated with Tunni and Jiido of the Lower Jubba Valley.

Arabs, who inhabited the Kismayu coast and islands parallel to the coast about 1660A.D, and to whom local tombs and ruins are attributed, exerted considerable influence on the formation of the present-day characteristics of the Bajuni were also routed by the Somali Garre whom the Bajuni claims as ancestors- perhaps they were at one time Garre clients.[21][22][23][24]

Support for such a thesis was mainly based on the fact that the Garre group is the most widely dispersed among the Somali clans.[1][25]

The Garre are a tribe of Somali origin who entering the country from the East, extended up the right bank of the Dawa as far as Galgala. This place is looked on as a tribal headquarter and is the burying place of the chiefs. According to the legend,

The first Garre ancestor, Aw Mohamed, crossed the Gulf of Aden into present day Somalia in 652AD. He was an Islamic scholar and a preacher. Because he was bearded, the Somalis named him "Garrow" or "Gardheer". He married a Hawiye woman who sired two boys and a girl. The first-born was Tuff and the second born Qur'an, and the daughter was named Makka.

Garre traditions generally recount movement southwards from the North-west corner of British Somaliland.

The scattering of Garre is also supported by the small remnants they supposedly left along the routes they took in their migration.The great Garre migration occurred after the fall of Ajuuraan empire. This is soo-called Boon Garre at the Afmadu, other Boon Garre at Gelib near the mouth of the River Jubba and still others on the RIver Tana who spoke not the dialect of their Darood neighbours rather the southern Somali dialect[1][26] of the Rahanweyn speech variety because they had lived in Rahaweyn speaking area between the Jubba and Shebelle rivers, and yet other who lived around Baardhere kept their own original Somali like language (Garreh Kofar-Af maahaw).

In the 18th century during the Gobroon dynasty Garre evolved a high degree of bilingualism when they controlled trade from Luuq to Boranaland,[27] the language of trade was Oromo language, and also when they interacted with Borana and other neighbouring community who spoke the language.[28][27][29][30]

The Garre are also mentioned in the Futuh Al Habasha : Conquest of Abyssinia as source dating back as far as the 16th century, by author: Shihabudin Ahmad bin Abd al-Qadir 'Arab Faqih or Arab Faqih. It is recorded that the Imam Mataan Bin Uthmaan Bin Khalid As-Somali[31][32] - He was a Garre-Sultan who headed the Somali tribe during the invasion of Abyssinia by Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi.

The Pre-Hawiye

The Pre-Hawiye, a much-reduced tribal-family, trace descent from an ancestor collateral to Irir, and are accordingly genealogically anterior to the Hawiya. Their traditions show them to have preceded the Hawiya in the general expansions of the Northern Somali towards the south. For these reasons Colluci has coined the term 'Pre-Hawiya' to distinguish them from the Hawiya to whom they are closely related.[1][33] The term "Pre-Hawiye", invented by Colluci, is used to describe any clan that is descended from one of the brothers of irir son of Samaale. . They also seen as quasi-ancestors of the Hawiye clan.

Garre pre-Hawiye group was the first group to occupy the land between the Jubba and Tana Rivers prior to the Oromo.[34]

The term pre-Hawiye is useful since there is no Somali equivalent; the Somali people divide the ancient Somalis into the Dir and Hawiya - (The Dir are universally regarded as being the oldest Somali stock), thus the pre-Hawiya Garre, for example, regard themselves as more closely related to the Hawiye than to the Dir. The largest pre-Hawiye clans are the Garre, Hawdle, Degodia, Galjaal and the Garre are the most ancient of all the pre-Hawiya clans. They occupied most of southern Somalia before the arrival of the Digil/Rahaweyn confederacy. Also, Bale province and Kenya's N.F.D. was inhabited by the Garre before the Oromo Boran and Warday entered the region.[35]

According to the Garre that inhabit the southern Ethiopia there ancestors originally came from Merca, on the Somali coast. Evidence for this comes from the fact that Garre tribesmen are found on the islands of Bajun, just off the Southern Somalia coast, and they are also found in the strength near Merca.[36]

Examination of ancient muslim graves found in the Garre country were found to be identical to those found in the North-Western Somalia; A.I. Curle made the following observation in 1933:

...around the mosque oat Au Bakadleh in the Hargeisa District of the British Somaliland, there are many graves of this type, exact replicas of those on the Dawa some found some 500 miles distance in the Garre country.[35]

The History of the Garre appears to be similar to that of the Gurgura. Both of these tribes were involved with trades; the Garre traded products from the southern Ethiopia to the Bajun Islands and Merca, while the Gurgura brought goods from the Hawash region to Zeila.[35]

Gerald Hanleys's description of the Somalis is extremely accurate. During the Second World War Hanley was in charge of Somali troops. His description of Mohamed, a Garre from El Wak, is fascinating:

"The Garre are even harder, fierce, more emotional than the Somalis( to whom they are related through the Hawiya tribal group), but this lad, Mohamed, was like a quivering black harp which burst into flames during emotional stress. He turned out to be the most savage, hysterical, loyal and dangerous human being i ever had with me in the bush. If he felt rage he acted upon it at once, with a knife, or with his nails and teeth, if he felt generous he gave everything away in sight, most of it your"[35]

Distribution

The pre-hawiye tribe comprises seven families excluding Irir:- Gardhere, Garjante, Yahabur, Meyle, Magarre, Hariire, Karuure. The largest pre-Hawiye clans are the Garre, Hawadle, Degodia, Galjaal and the Garre are the most ancient of all the pre-Hawiye clans. The Hawadle live north of the river Shebelle, adjacent to the Marehan Darod and just north of the Abgaal Hawiye. The Galjaal live next to the Hawadle, they are also found further south near the River Jubba. The Degodia inhabit northern kenya and southern Ethiopia. The Garre are the most important tribe of the pre-Hawiye family.[37] They occur in four large autonomous groups: on the lower reaches of the Shebelle in Audegle District around Dolo on the upper jubba, between the Webi Gestro and the Webi Mana in contact and to some extent intermixed with the Arsi Oromo, and to the south-west between the Ajuran and Degodia Somali and the Boran Galla of the Northern Frontier Province of Kenya.[15][37] The northernmost group adjacent to the Arsi Oromo have acquired some features of Borana Oromo culture; Galla and Somali are both spoken. Arsi Oromo villages are intermixed with those of the Garre (Gurra) but are kept separate from those of the Somali.[15][37] The Garre (Gurra) of this region have traditions similar to those of the other Garre groups and consider themselves Somali rather than Galla.[15][37] Garre traditions generally recount movement southwards from the North-west corner of British Somaliland. As a whole, the Garre are nomadic pastoralists with large numbers of camels, sheep, goats and where the habitat is suitable, they settle and domesticate their cattle.

Proto-Reewin

The Proto-Reewin group were probably the first Cushitic group to enter what is the southern part of modern day Somalia, around the end of the second century B.C.. The Proto-Reewin, the ancestors of the modern Reewin families (Digil and Mirifle), occupy a unique position both linguistically and culturally in the historical development, migration and settlement in the area south of the Shabelle River.

The name is not pronounced "Rahanweyn" as traditionally suggested, but "Reewin". It is a compound name which can be divided into ree=reer=Family; "win=weyn=old" "the old family". This definition of the name Reewin might indicate that Reewin (Digil and Mirifle) might have once been the first Somali speaking group that established itself in what is today modern Somalia, whence the rest of the Somali clans diverged slowly and through time developed their distinct northern dialect. But since the northern Somalis were separated from the Reewin-speaking people for at least 1500 years, their language might have undergone a mutation process

Rahanweyn tribes are aggregates of many diverse clan attached to a small original nucleus of Rahanwein,[38] who form the dominant eponymous clan and provide the skeletal framework in each tribe. In many cases, however, this type of organization, dependent for its structure on a dominant clan, is superseded by a system of territorial groups whose political relations are not expressed genealogically.[38] In the Rahawein family itself there are only three orders of segmentations between the group-name and ancestor Rahawein, and the individual tribes which constitute the family making about 40% of somali population. The Rahaweyn consists no so much of groups that derive from preceding groups in an extensive hierarchy of segmentation, as simply of large collateral coalitions. The name "Rahaweyn" ( "large crowds") is itself suggestive of federation.[38] The Sab, who number about a quarter millions are found in Somalia south of the Hawiya, mainly along the Juba river. They are segmented into three families: The Digil, Rahaweyn and Tunni of which the last two are numerically the most important. The Rahaweyn and Tunni derive from the Digil who although have been superseded in strength still survive as a small independent confederacy.[39] The Garre joined Rahaweyn constituent sub-clans of Digil, forming a part of the Rahaweyn confederation of clans.[2][20] known as "Toddobaadi aw Digil"

Expansion into the Boranaland

The Boran say that long ago they all lived in Liban. The head-quarters of their Kings and their religion (Wak) was near Darar, which is still a great religious centre. Many years ago a number of them made an invasion to the south-west, across the Dawa River, into which the country was occupied by the Wardey, who were a "suffara" (Somali) tribe. The Wardey were driven out and went south-east towards Aji between Wajir and Kismayu. The Invader settled in the conquered country, spread and penetrated south as far as wajir. The true Boran countries are, however Liban and Dirri.[40]

Many years after these event there was an invasion from the east, into the most eastern Boran country, by Muslim of Somali origin. These people were camel owners, whereas the Boran are essentially cattle herds. The Muslim drove back the Boran to the West and occupied the country probably up to about latitude 39°30'. After an unknown period they commenced to withdraw eastwards, but not en masse. Those who penetrated furthest west, weakened by the exodus of many of their number, came under the influence of the boran. These are the Gabra Miggo generally "Gabra" and sometime "Gabra Gelli", Gabra in the Boran language signifies "slave" Gelli "Camel".[40]

The Garre were the descendants of the Muslim who drove back the boran to the west, but unlike their brethren who have become the Gabra migo, they remained in the country they had occupied in the sufficient numbers to maintain their independence.[40]

Previous to the abyssinian occupation of the Boran country, the most westerly section of the Garre used at times to fight the Boran; both sides claim to have been the stronger. The chief of the Garre from muddo westwards is Ali Abdi, who is looked upon by all the Garre people as far as the Ganale as the greatest Mullah and chief of the tribe. Ali Abdi stated that the Garre originated from the Hawiye somali, and came long ago from Merka on the coast, north-east of Kismayu

The Garre used to trade with the Boran, receiving cattle and ivory in exchange for cloth. The boranas are not traders, and do not leave their country unless they are frightened,[40][41] although no tribute was paid by the Garre to the Boran, the western Garre chief used exchanged presents with the Borana Kings. There seems to be no doubt that from El-Wak eastwards neither the Garre nor any other of the tribes have ever had any such relations with the Borana

El Wak is from report the most important place between the Ganale River and the Boran country. Besides the Garre, who were the most numerous, there also other somali tribe who overlap each other and intermix freely i.e marehan, murulle etc

Gabra

After the invasion from the east, into the most eastern Boran by garre, later after some period they commenced to withdraw eastwards, but not en masse. Those who penetrated furthest west, weakened by the exodus of many of their number, came under the influence of the boran. These are the Gabra Miggo generally "Gabra" and sometime "Gabra Gelli", Gabra in the Boran language signifies "slave" Gelli "Camel".[40] They stayed to become borana clients

The relations to the Boran became peculiar. They were divided up among different sub-tribes of the boran, and given the name of the sub-tribes to which they were attached. They lost all their national pride, and were only too glad to be able to call themselves "Boran" for the sake of protection. Gabra migo often live in the same settlement with the boran, but have their own separate zarebas. They do not intermarry with Borana nor have they adopted the latter's customs or religion although they retain very little of their own. The Boran gave them protection, and helped themselves to their loading camels, but left them their milk camels to live upon. The boran exacted little, if any, manual labour from them.

Gabra are is divided into Malba and Miigo. They are both the children of Weytaan Derraawe Fukaashe Quranyow Garre Addow.

Bajuni-(Katwa)

J.A.G. Elliot, whose traditions collected among the Bajun in the 1920s remain in many respects the fullest and most useful, is emphatic that the Bajun Katwa were, in origin, Garre( Gerra, Gurreh). This alternative is corrobated by a historical tradition of the Garre themselves.[42]

An unpublished Garre tradition collected at Mandera c.1930 by Pease, a british colonial administrator, touches on the Garre-Katwa link. After the great Garre migration is soo-called Boon Garre at the Afmadu, other Boon Garre at Gelib near the mouth of the River Jubba. The majority crossing the Juba but a small party from the Killia, Bana and Birkaya [Sections].. turned aside at the Juba to make for the coast between Kismayu and Lamu, where they settled with the Bajun[45]

Garre exerted considerable influence on the formation of the present-day characteristics of the Bajuni whom the Bajuni-katwa claims them as their ancestors -perhaps they were at one time Garre clients.[21][22][23][24][45]

Garre Dynasty

The Garre tribe has had several dynasties throughout their history. Most of their dynasties involved often cooperation and completeness with other tribes, leading to a complex and dynamic political landscape. One of the most notable dynasties was the Ajuuraan sultanate, which ruled parts of southern Somalia from the 13th to the 17th century. The Garre tribe was one of the clans that formed the backbone of the Ajuran Sultanate's military and the economic power. They played a key role in the sultanate's economic success. They were known for their long-distance network that extended from Kismayo to luuq to modern day mooyale .

Another significant dynasty was the Geledi Sultanate, which ruled parts of southern Somalia from the late 18th to the late 19th century, centered around the town of Afgooye, located west of Mogadishu.The Garre people were one of the clans that inhabited the region around the Geledi Sultanate, and they played a significant role in the sultanate's military and economic power.The Garre people were known for their bravery and fighting skills, and they served as soldiers and commanders in the Geledi army. They also participated in long-distance trade networks that extended to Arabia, India, and other parts of Africa i.e Ethiopia, contributing to the sultanate's economic success.

The Garre tribe is mentioned in "Futuh Al-Habasha: The Conquest of Abyssinia" (also known as "Futuh Al-Habasa"), which is an historical account of the Ethiopian-Adal war that occurred in the 16th century. The Garre people, along with other Somali clans such as the Issa and the Dir, are mentioned as having supported the Adal Sultanate in its conflict with the Ethiopian empire. The author of "Futuh Al-Habasha," Shihab al-Din Ahmad ibn Abd al-Qadir al-Fatati, describes Sultan Mataan Cismaan Khalid was a powerful warrior from the Garreh, Girreh tribe. He had 3000 men under his command and 500+ horsemen. He provided valuable military support to the Adal forces, including cavalry and archers.

Demography and Social Organisation

Most Garre are nomadic herdsmen, seasonally migrating with their camels, sheep, and goats. They live in portable huts made of bent saplings covered with animal skins or woven mats. Their collapsible tents can easily be loaded on pack animals and moved with the herds. The wealth of most Garre is in their herds. Although the husband remains the legal owner of the herd, his wife controls part of it.

Garre villages consist of several related families. Their huts are arranged in a circle or semi-circle surrounding the cattle pens. Villages are enclosed by thorn-shrub hedges to provide protection from intruders or wild animals. The men's responsibilities include caring for the herds, making decisions dealing with migration, and trading. The women are in charge of domestic duties, such as preparing the meals, milking the animals, caring for the children, and actually building the home. Like other nomads, the Garre scorn those who work with their hands, considering craftsmen a part of the lower class. The moving patterns of Garre nomads are dependent upon climate and the availability of grazing land. If water or grazing land becomes scarce, the families pack up their portable huts and move across the desert as a single, extended family unit. The Garre are quite loyal to one another, spreading evenly across the land to make sure that everyone has enough water and pasture for his herds.

Just like other Somalis, Garre receive their fundamental social and political identity at birth through membership of their father's clan.[46] Clan identity is traced exclusively in the male line through their father's paternal genealogy (abtirsiinyo: literally “counting ancestors,” in Somali). Children, at an early age, are taught to recite all their paternal ancestors up to the clan ancestor and beyond that the ancestor of their “clan-family.”.[47]

Somali clans are grouped into clan bonds or clan alliances formed to safeguard the mutual interests and protect the members of these alliances, of which Garre lies here under Hawiye with the Abgaal, Habargedir, Hawadle, Mursade, Rahwein, Murule, Ajuran, and among many others sub-clans.[48] On the other hand, the Dir, largely in Somaliland, mix well with the Isaaq, the Garre and the Degodia, with closer sub-clans being the Biyamal, Gadsan, and Werdai among others. The sub-clans closer to the Isaaq include Habar Awal, Habar Jalo, Habar Yunis, Edigale, and Ayub among others while those closer to the Digil are the Geledi, Shanta Aleen, Bagadi, and Garre, among others.[48]

Socioeconomic

Garre are known for their large and majestic camels among the somalis.[49] Despite the heavy emphasis on camel husbandry the production system of the Garre includes important cattle and crop components. It is thus an example of a maximally diversified agro-pastoral system entailing very complex household strategies.Thus, the Garre differ both from the northern and central Somali and the agro-pastoralists of the Bay region; from the former by their agro-pastoralism, from the latter by their heavier emphasis on camels, their higher mobility and a segmentary agnatic organisation closer to the northern clan families.[50][51][52]

The Garre were renowned as breeders of burden camels, they supplied the Somalis and Oromos caravaneers of the Jubba Basin the eighteenth century and probably much earlier.[53] They are classified as true nomads along with Galjeel for they moved inter-riverine region seasonally, often with large herds of camels. The young camel-herders of these groups are known for their distinctive Afro-style hair-do called in Somali guud.[54]

Majority of Garre camel owners have been integrated into commercial camel milk trade supplying Mogadishu.While most pastoral producers in Africa have become petty commodity producers linked to the national markets, their integration has usually been through the market for animals (or meat) rather than milk.[51]

The nomadic Garre also took part in trade as caravaneers, they had the reputation of being the most honest at the work.[55] They were able to also profit by the trade which passed by their settlement.

Following the decline of the Ajuraan state in the mid-seventeenth century and after the scene of many conflicts during the age of Oromo expansion, was gradually becoming stabilized. Along that frontier there evolved a number of bilingual trading settlements, coupled with the integrating force of islam, these developments facilitated the creation of regional exchange networks. The most important inland market towns in southern Somalia were Luuq[56] and Baardheere, on the Jubba River; Baydhabo (Baidoa) and Buur Hakaba in the central inter-river plain; and Awdheegle and Afgooye along the lower Shabeelle. Since most of these towns were situated in good agricultural country, they were able to supply caravans with foodstuffs and other provisions. In this way, the long-distance caravan trade helped stimulate the local market economy.[57][52]

Although the inland market centers were small—only the towns along the Shabeelle numbered more than two thousand permanent residents—they were frequented by nomads, farmers, and peddlers from the surrounding districts. In essence, they were small "ports of trade" that offered security and a degree of political neutrality to buyers and sellers from a variety of different clans and locales.

This was essential, since long-distance trade in southern Somalia—as in the north—was segmented. Goods originating in the Jubba basin were brought to the towns of Luuq and Baardheere in caravans manned by traders from upcountry clans: Garre and Ajuraan. From the Jubba River towns, Gasar Gudda, Eelay, and Garre traders carried the goods to Baydhabo and Buur Hakaba, to Awdheegle and Afgooye. Garre and Elay monopolized the interior route and also controlled caravan transport towards the coast, mostly sent to Marka or Benaadir.[58]

Here are of some of the camel branding of Quranyow 1, Quranyow 2, Tuuf 1 Tuuf l 2, Tuuf 3

Distribution

Garre are said mostly to be found in southern Somalia, on the Lower reaches of the Shabelle River; Afgooye, around Dolo around the upper Jubba; between Webi Gesho and Webi Maana River, Qoroyoley, Merca, and Awdhegle, Kurtunwaarey and Kaxda District & Kofur in Mogadishu, El Wak District in Gedo Jubaland.[59][60][61] and in the upper reaches of Dawa River on the borders of Ethiopia and Kenya.[1] This, in turn, is based on the Garre oral traditions( collected at the beginning of the century) that they migrated from the upper reaches of the Jubba River along the west side of the River Afmadu. In Ethiopia, they live in Moyale, Hudet, Mubarak, Qadaduma, Suruba, Raaro, Lehey and Woreda of Dawa zone.[62] In Kenya, the Garre tribe inhabit Mandera County-(The largest population and composition of Garre live in Mandera County, making them the single largest clan in Mandera County),[63] Wajir, North Moyale, as well as part of Isiolo County.

Both the Garre and Ajuran claim to have lived in their present location in Mandera District (formerly Garreh District) and the Northern part of Wajir District before the sixteenth-century expansion of the Oromo, According to tradition Gurreh District was originally inhabited by a Semitic tribe ben-Izraeli before inhabited by Garre tribe.[64] before setting out to prospect for a new country. They travelled down the Juba through Rahaweyn to Kofar (confor) and decided it was a good country.[65] The Confer (Kofar) country lies beyond Rahanweyn in the coastal area, the principal Gurreh towns or villages being Shan and Musser on the Owdegli i.e. the lower reaches of the Shebelle River where it runs parallel with and close to the sea coast between Mogadishu and Merca. Then when well established and prosperous the Garre penetrated into Rahanweyn and sent trading safaris and settlers further in-land until they reached Lugh and Dolo and re-entered the Gurreh district (today Mandera District) and worked up the Dawa district (sic: actually 'river') again, trading mostly but also making settlements and farms.[64][65]

Garre is divided into four linguistic clusters, which cross-cut other criteria of differentiation like clanship. Some of them speak an Oromo dialect close to the one of the Boran, while some speak Af Maay Maay and yet others Af Garreh (Af mahaw). The latter two are closely related Somali-like languages but are kept clearly apart by their speakers. There are also Garre who speak Somali proper. Oromo is a different language well beyond the comprehension of speakers of any of these Somali dialects. It belongs to the same lowland branch of the East Cushitic languages as the Somali-type languages, but internal differentiation within this branch is high. The fact that the Garre are also divided between three nation-states (Kenya, Ethiopia, and Somalia) has nothing to do with this linguistic differentiation since speakers of all four languages are found among the Garre of all three states. The only language which is spoken exclusively by Garre appears to be Af mahaaw, but to the outside observer, it is difficult to distinguish that language from Rahanweyn dialect (also called Maymay), which is spoken by hundreds of thousands of non-Garre, namely Somali of the Rahanweyn clan cluster. It does happen that Garre who do not share one of these Cushitic languages are obliged to converse with each other in languages from totally different language families, like Swahili or English which they have acquired at school, an institution frequented by only a minority of them, mostly for short periods.[66] Arabic is also spoken as a secondary or trade language. Like other Somali, the Garre are typically tall and slender with long, oval faces and straight noses. Their skin colour varies from jet black to light brown.

.jpg.webp)

Af-Garre (Af-mahaaw) is spoken in the districts of Baydhaba, Dhiinsor, Buurhakaba and Qoryooley is one of the heterogeneous dialect of Somalia; in fact, some Garreh Koonfur dialects (those in Buurhakaba and Qoryooley) have, for instance, preserved the conjugations with prefixes to date, while others (those of Baydhaba) have already given it up. Also, the typical Digil plural morpheme—to has been replaced in some Garre. dialects (especially in those around Baydhaba) by the common southern Somali morpheme—yaal. Although Reer Amiir are not Garre at all, their idioms belong to this dialectal group.[67]

Garre genealogy and clan structure

The following genealogy has been derived from the work of Professor L.M.Lewis, also taken also from the World Bank's Conflict in Somalia: Drivers and Dynamics[68] from 2005 and the United Kingdom's Home Office publication, Somalia Assessment 2001,[69] and The Total Somali Clan Genealogy (second edition), African Studies Centre Leiden, Netherlands[16] The tribes of Garre have a well-defined patrilineal genealogical structure,

Lineage

The lineage of Garre Mohamed-Garre bin Yusuf (Gardere) bin Samaale, and subsequently Samaale, traced from Abu Talib ibn Abd al-Muttalib

| Abd al-Muttalib | Fatimah bint Amr | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fatimah bint Asad | Abu Talib ibn Abd al-Muttalib | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aqil ibn Abi Talib | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Muuse | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Muhammad al-Muhtadi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mahdi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Xubli | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ahmad | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cabdirahman | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Loxan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 'Waloid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hill | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Samaale | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yusuf(Gardheere) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Riidhe | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Garjante | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cadow | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Garre(Karre) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Garre are divided into the Tuff and Quranyow sub-clans. While the Tuffs are further divided into the Ali and Adola groups, the Quranyow are divided into the Asare and Furkesha.[70][63]

The eponymous ancestor of the Garre clan:

| Hill Abroone Samaale Gardheere Garre | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tuuf | Mohamed | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cadoole | Caali | Makka | Quranyow | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deeble | Dool | Aw Maki | Qalowle | Sabdow | Tawlle | Furkaashe | Qeyliyow | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Malxase | Kalxase | Carrowyne | Geedi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aw Sotowle | Aw Duurre | Aw Buur | Karaare | Kariile | Meerti | Miinxaama | Shaalashane | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aw Shuulle | Aw Dooy | Aw Barre | Aw Kalbiyood | Taalle | Kuulle | Carqaale | Dirwalaal | Caarifa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reer muug | Meeyd | Abtugay | Tawaadle | Hagar Kalweyne | Aw Rooble | Aw Xareed | Aloe | Saare | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reer Ayse | Reer Maxamed | Maqabuul | Aw Cabdi | Aw Masuge | Aw Gurow | Daamid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kelmaal | Kuuble | Edeeg | Midig | Cukaad | Habar Qosol | Habarey Reer Meeg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shidoole | Durafle | Dugulle | Mogobow | Reer Barre | Banne | Killiya | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Desdemet | Burusade | Aw Farax | Aw Salale | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aw Dooble | Aw Faqay | Reer Macalin | Caydabole | Hedow | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bahura | Reer Ubur | IImiilla | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Erdhow | Dayle | Cali | Celi | Maxamuud | Reer warasamaal | Reer Ciise | Reer Habow | Deerow | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Waladay | Odogow | Berkay | Uurdeeq | Deraawe | Owtire | Suqutre | Galweesh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Celiye | Duraale | Dumaale | Miriid | Aw Maxamed | Weytaan | Walaasame | Geytaan | Isgeytaan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Warasiley | Cisoobe | Gabra | Uuryeere | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aw Kheeyrow | Aw Libow | Ciribow | Qoxow | Beged | Duurre | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tuurgaale | Xamaale | Geer Caade | Reer Faqi | Jilaal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Qalaafow | Lehow | Dayle | Madiile | Aw Xintir | Aw Saaxi Cabdi | Aw Sugow Dugow | Aw Sugay Bege | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aw Duubow | Aw Maxamed | Ableelo | Abliire | Harti Gaanle | Aw Maganey | Aw Salaanle | Aw Daayow | Aw Kaayow | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes Gabra are is divided into Malba and Miigo. They are both the children of Weytaan Derraawe Fukaashe Quranyow Garre. |

Sources

|

In history, Identities on the Move: Clanship and Pastoralism in Northern Kenya, by Gunther Schlee, Voice and Power, by Hayward and UNDP Paper on Kenya, the Garre are divided into the following clans.[64][71]

Notable people

Politicians

- Billow Kerrow, Kenyan senator from Mandera County

- Adan A. Mohamed, Kenyan cabinet secretary for industrialization and enterprise development

- Ibrahim Ali Roba, governor of and current Kenyan senator from Mandera County

- Mohamed Maalim Mohamud, Kenyan senator from Mandera County

References

- Ahmed, Ali Jimale. (1995). The invention of Somalia. Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 0-932415-98-9. OCLC 31376757.

- Ahmed, Ali Jimale. (1995). The invention of Somalia. Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press. p. 122. ISBN 0-932415-98-9. OCLC 31376757.

- "World Bank: Conflict in Somalia: Drivers and Dynamics" (PDF). World Bank: 56. January 2005.

- Marchal, Roland (1997). Studies on Governance. United Nations Development Office for Somalia.

- Verdier, Isabelle (1997). Ethiopia: The Top 100 People. Indigo Publications. ISBN 978-2-905760-12-8.

- Cassanelli, Lee V. (2016-11-11). The Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, 1600-1900. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-1-5128-0666-3.

- Ali, Ibrahim (1993). Origin and history of the Somali people. Eget forlag. ISBN 0-9518924-5-2. OCLC 769997578.

- Reese, Scott (2008-06-30). Renewers of the Age: Holy Men and Social Discourse in Colonial Benaadir. BRILL. p. 41. ISBN 978-90-474-4186-1.

- "According to 'Aydarūs' narrative, Barawe was founded around the year 900 C.E. by an individual from the pastoral Garreh clan known as Aw 'Alī" .. Aydarus from Bughyat al-Āmāl

- Abdullahi, Nouh (2012). Qaamuuska Af-Soomaalig. Rome: Roma TrE-Press. ISBN 978-88-97524-02-1.

- Hussain, Seqend (2018-05-15). Mai-Mai (Somali) Dictionary: Mai-Mai to English. Authors Press. ISBN 978-1-948653-08-4.

- Hirbo, Jibril Boru. "Complex Genetic History of East African Human Populations" (PDF). University of Maryland, College Park. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- "E-V12 YTree".

- Ahmed, Ali Jimale (1995-01-01). The Invention of Somalia. The Red Sea Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780932415998.

- Lewis, I. M. (2017-02-03). Peoples of the Horn of Africa (Somali, Afar and Saho). doi:10.4324/9781315308197. ISBN 9781315308197.

- Abbink, G. J. (2009). "The Total Somali Clan Genealogy (second edition)". ASC Working Paper Series (84).

- Schlee, Günther (2007). Identities on the move : clanship and pastoralism in northern Kenya. Gideon S. Were Pr. p. 28. ISBN 978-9966-852-20-5. OCLC 838094592.

- But according to legend and oral literature Aw Mohamed (Garrow) bore two sons, First born being Tuuf aw Mohamed(Garrow) and Qur'an Aw Mohamed(Garrow) and Makko Mohamed (Garrow) daughter

- Legend 2:- Aw Garre had two sons, Mohamed Garre and Tuuf Garre. Mohamed was the eldest son, gave birth to Quran and died. Quranyow was raised by his uncle Tuuf and later married his cousin Makko Tuff and sired two sons. Assare and Furkesha. Tuuf sired, Ali and Adola

- Worldbank, Conflict in Somalia: Drivers and Dynamics, January 2005, Appendix 2, Lineage Charts, p.55 Figure A-1

- I. M., Lewis (1994). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho (Ethnographic Survey of Africa; North Eastern Africa, Part I). Haan Associates; New Edition. pp. 42–43. ISBN 1874209-56-1.

- Eastman, Carol M.; Nurse, Derek; Spear, Thomas (1991). "The Swahili: Reconstructing the History and Language of an African Society, 800-1500". Anthropologica. 33 (1/2): 231. doi:10.2307/25605624. ISSN 0003-5459. JSTOR 25605624.

- https://langsci-press.org/catalog/view/192/1510/1623-1

- scientifique., Clem, Emily., Éditeur scientifique. Jenks, Peter., Éditeur scientifique. Sande, Hannah., Éditeur (2019). Theory and description in african linguistics : selected papers from the 47th annual conference on african linguistics. ISBN 978-3-96110-205-1. OCLC 1154621726.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lewis, I. M. (1994). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho. HAAN. ISBN 978-1-874209-56-0.

- Mauro Tosco. 2012. The Unity and Diversity of Somali Dialectal Variants. In Nathan Oyori Ogechi and Jane A. Ngala Oduor and Peter Iribemwangi (eds.), The Harmonization and Standardization of Kenyan Languages. Orthography and other aspects, 263-280. Cape Town: The Centre for Advanced Studies of African Society (CASAS).

- Boorana had established and maintained peaceful trade with Garre since the middle of eighteenth century (Goto 1972:42)

- Cassanelli, Lee V. (11 November 2016). The Shaping of Somali Society : Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, 1600-1900. ISBN 978-1-5128-0666-3. OCLC 1165451500.

- Karlström, Mikael (August 1998). "Being and Becoming Oromo: Historical and Anthropological Enquiries". American Ethnologist. 25 (3): 533–534. doi:10.1525/ae.1998.25.3.533. ISSN 0094-0496.

- ʻArabfaqīh, Shihāb al-Dīn Aḥmad ibn ʻAbd al-Qādir. 1974. Tuḥfat al-zaman: aw, Futūḥ al-Ḥabashah : al-ṣirāʻ al-Sūmālī al-Ḥabashī fī al-qarn al-sādis ʻashr al-mīlādī. [al-Qāhirah]: al-Hayʼah al-Miṣrīyah al-ʻĀmmah lil-Kitāb

- ibn Abd al-Qadir al-Jizan, Shihab al-Din Ahmad (2005). The Conquest of Abyssinia: Futuh Al Habasa. Tsehai. ISBN 0972317260.

- I. M., Lewis (1994). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho (Ethnographic Survey of Africa; North Eastern Africa, Part I). Haan Associates; New Edition. pp. 25–26. ISBN 1874209-56-1.

- Ahmed, Ali Jimale (1995). The Invention of Somalia. The Red Sea Press. ISBN 978-0-932415-99-8.

- Ali, Ibrahim (1993). Origin and history of the Somali people. Wales: Eget forlag. ISBN 0-9518924-5-2. OCLC 769997578.

- Ibrahim, Ali (1993). Origin and History of the Somali People: Vol 1. Wales: Punite Books. p. 69. ISBN 0951892452.

- I. M., Lewis (1994). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho (Ethnographic Survey of Africa; North Eastern Africa, Part I). Haan Associates; New Edition. p. 27. ISBN 1874209-56-1.

- I. M., Lewis (1994). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho (Ethnographic Survey of Africa; North Eastern Africa, Part I). Haan Associates; New Edition. pp. 34–40. ISBN 1874209-56-1.

- I. M., Lewis (1994) (1994). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho (Ethnographic Survey of Africa; North Eastern Africa, Part I). Haan Associates; New Edition. pp. 15–18. ISBN 1874209-56-1.

- Office., Great Britain. Foreign (1904). Report by Mr. A.E. Butter on the survey of the proposed frontier between British East Africa and Abyssinia. Printed for H.M.S.O. by Harrison and Sons. pp. P9 11–14. OCLC 864812693.

- Office., Great Britain. Foreign (1904). Report by Mr. A.E. Butter on the survey of the proposed frontier between British East Africa and Abyssinia. Printed for H.M.S.O. by Harrison and Sons. p. 32. OCLC 864812693.

- James., De Vere Allen (1993). Swahili origins : Swahili culture & the Shungwaya phenomenon. James Currey. ISBN 0-85255-076-6. OCLC 877643822.

- Reynolds, David West. "Swahili Ghost Town." Archaeology vol. 54 no. 6 (November/December 2001): 46.

- A fight between the Kiliya and other sections of the Gurreh tribe in the town and resultant fire. A reason which lead to its abandonment by the population. Bajun claim a Kiliya-Gurreh ancestry

- James., De Vere Allen (1993). Swahili origins : Swahili culture & the Shungwaya phenomenon. James Currey. ISBN 0-85255-076-6. OCLC 877643822.

- Lewis, I. M. (1999). A pastoral democracy: a study of pastoralism & politics among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. James Currey. ISBN 0-85255-285-8. OCLC 40683120.

- Samatar, Ismail Abdi (2011). "Debating Somali Identity in a British Tribunal: The Case of the BBC Somali Service" (PDF). Bildhaan. 10: 36–88. ISSN 1528-6258.

- "THE ITPCM INT'L COMMENTARY: Somalia Clan And State Politics" (PDF). THE ITPCM INTERNATIONAL COMMENTARY: Somalia Clan and State Politics. IX (34). December 2013.

- Mukasa-Mugerwa, E. (1981-01-01). The Camel (Camelus Dromedarius): A Bibliographical Review. ILRI (aka ILCA and ILRAD).

- Urs J., Herren (1992). "Nomadic Peoples". Nomadic People. 30: 97.

- Herren, Urs J. (1992). "Cash from Camel Milk: The Impact of Commercial Camel Milk Sales on Garre and Gaaljacel Camel Pastoralism in Southern Somalia". Nomadic Peoples (30): 97–113. ISSN 0822-7942. JSTOR 43123360.

- V., Cassanelli, Lee (11 November 2016). The Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, 1600-1900. ISBN 978-1-5128-0666-3. OCLC 979729494.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The early political history of the Garre is summarized in E. R. Turton, "Bantu, Galla, and Somali Migrations in the Horn of Africa: A Reassessment of the Juba/Tana Area," Journal of African History 16 (1975): 528-31. On the role of the Garre as caravaneers, see Ugo Ferrandi, Lugh: Emporio commerciale sul Giuba (Rome, 1903), pp. 113, 150-51, 341-67 passim.

- Myrddin, Lewis, Ioan (1995). Understanding Somalia : guide to culture, history and social institutions. HAAN Assoc. ISBN 1-874209-41-3. OCLC 247676076.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ferrandi p.343

- By 1800 the merchants of Luuq, a small town on the upper Jubba River, enjoyed extensive trading contacts with the surrounding Oromo districts: a European observer reported from Muscat in 1811 that Luuq was sending "immense quantities" of slaves and ivory to the coast near Baraawe. Through the remainder of the century, Luuq retained its position as the most important trading town of the southern Somali interior. By the second half of the nineteenth century, ivory traders from Baraawe were known in Borana country and were reported to be trafficking among the Rendille near Lake Turkana.

- References to internal trade within southern Somalia are found throughout Ferrandi, Lugh, esp. pp. 314-68; this work is an invaluable source for the study of late nineteenth-century regional commerce.

- Reese, Scott Steven (1996). Patricians of the Benaadir: Islamic Learning, Commerce and Somali Urban Identity in the Nineteenth Century. University of Pennsylvania.

- "Conflict Early Warning and Response Mechanism (CEWARN) project by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), a regional organization of states (Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Sudan and Uganda) Based in Djibouti". CEWARN: | p. 53. September 2013.

- "CEWARN - Conflict Early Warning and Response Mechanism: Somalia CEREWU - Conflict Early Warning Early Response Unit; From the bottom up: Southern Regions - Perspectives through conflict analysis and key political actors' mapping of Gedo, Middle Juba, Lower Juba, and Lower Shabelle". CERWAN. September 2012.

- "Norwegian country of origin information center Landinfo". Landinfo: |p. 8. October 18, 2013.

- "Socio economic conditions affecting vulnerable groups in the brutal and urban centers in Liban Zone". Ethiopian Somali National Regional State – via Prepared by Dr. Ahmed Yusuf Farah, Anthropologist, UNDP Emergencies Unit for Ethiopia.

- "Dynamics and Trends of Conflict in Greater Mandera" (PDF).

- Schlee, Günther (1989-01-01). Identities on the Move: Clanship and Pastoralism in Northern Kenya. Manchester University Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780719030109.

- J.W.K, Pease (1928). An Ethnological Treatise Of The Gurreh Tribe. KNA.

- Schlee, Günther (2010). How Enemies are Made: Towards a Theory of Ethnic and Religious Conflict (NED - New edition, 1 ed.). Berghahn Books. pp. 160–161. ISBN 978-1-84545-779-2. JSTOR j.ctt9qd3d3.

- Andrzej, Zaborski (1986). Map of Somali Dialects In The Somali Democratic Republic. Gemsamtherstellung: HELMUT BUSKE VERLAG HAMBURG. pp. 24–25. ISBN 3871186902.

- Marchal, Roland (2019-03-01). "Motivations and Drivers of Al-Shabaab". War and Peace in Somalia. Oxford University Press. pp. 309–317. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190947910.003.0027. ISBN 978-0-19-094791-0. Retrieved 2020-12-29.

- "Somalia Assessment" (PDF). Somalia Assessment 2001. 2001.

- Hayward, R. J.; Lewis, I. M. (2005-08-17). Voice and Power. Routledge. p. 242. ISBN 9781135751753.

- Ali, Ibrahim (1993). Origin and history of the Somali people. Wales: Eget forlag. p. 72. ISBN 0-9518924-5-2. OCLC 769997578.

Sources

- Cruciani, F.; La Fratta, R.; Trombetta, B.; Santolamazza, P.; Sellitto, D.; Colomb, E. B.; Dugoujon, J.-M.; Crivellaro, F.; et al. (2007), "Tracing Past Human Male Movements in Northern/Eastern Africa and Western Eurasia: New Clues from Y-Chromosomal Haplogroups E-M78 and J-M12", Molecular Biology and Evolution, 24 (6): 1300–1311, doi:10.1093/molbev/msm049, PMID 17351267, archived from the original on 2017-10-10