Fulmar

The fulmars are tubenosed seabirds of the family Procellariidae. The family includes two extant species and two extinct fossil species from the Miocene.

| Fulmar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Northern fulmar | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Procellariiformes |

| Family: | Procellariidae |

| Genus: | Fulmarus Stephens, 1826 |

| Type species | |

| Procellaria glacialis (northern fulmar) Linnaeus, 1761 | |

| Species | |

| |

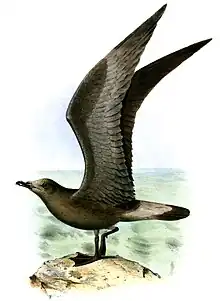

Fulmars superficially resemble gulls, but are readily distinguished by their flight on stiff wings, and their tube noses. They breed on cliffs, laying one or rarely two eggs on a ledge of bare rock or on a grassy cliff. Outside the breeding season, they are pelagic, feeding on fish, squid and shrimp in the open ocean. They are long-lived for birds, living for up to 40 years.

Historically, the northern fulmar lived on the Isle of St Kilda, where it was extensively hunted. The species has expanded its breeding range southwards to the coasts of England and northern France.

Taxonomy

The genus Fulmarus was introduced in 1826 by the English naturalist James Stephens.[1] The name comes from the Old Norse Fúlmár meaning "foul-mew" or "foul-gull" because of the birds' habit of ejecting a foul-smelling oil.[2] The type species was designated by George Gray in 1855 as the northern fulmar .[3][4]

As members of Procellaridae and then the order Procellariiformes, they share certain traits. First, they have nasal passages that attach to the upper bill called naricorns. The bills of Procellariiformes are unique in being split into between seven and nine horny plates. Finally, they produce a stomach oil made up of wax esters and triglycerides that is stored in the proventriculus. This can be sprayed out of their mouths as a defence against predators and as an energy rich food source for chicks and for the adults during their long flights.[5] It will mat the plumage of avian predators, which can lead to their death. Fulmars have a salt gland that is situated above the nasal passage and helps desalinate their bodies, due to the high amount of ocean water that they imbibe. It excretes a strong saline solution from their nose.[6]

Extant species

The genus contains the following two species.[7]

| Image | Scientific name | Common Name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fulmarus glacialis | northern fulmar | North Atlantic and North Pacific oceans. |

| Fulmarus glacialoides | southern fulmar | islands around Antarctica such as the South Sandwich Islands, South Orkney Islands, South Shetland Islands, Bouvet Island, and Peter I Island |

Fossils

Two prehistoric species have been described from fossil bones found on the Pacific coast of California: Fulmarus miocaenus (Temblor Formation) and Fulmarus hammeri from the Miocene.[8]

Description

The two fulmars are closely related seabirds occupying the same niche in different oceans. The northern fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis) or just fulmar lives in the North Atlantic and North Pacific, whereas the southern fulmar, (Fulmarus glacialoides) is, as its name implies, a bird of the Southern Ocean. These birds look superficially like gulls, but are not closely related, and are in fact petrels. The northern species is grey and white with a yellow bill, 43 to 52 cm (17–20 in) in length with a 102 to 112 cm (40–44 in) wingspan.[9] The southern form is a paler bird with dark wing tips, 45 to 50 cm (18–20 in) long, with a 115 to 120 cm (45–47 in) wingspan.

Behavior

Breeding

Both recent species breed on cliffs, laying a single white egg.[9] Unlike many small to medium birds in the Procellariiformes, they are neither nocturnal breeders, nor do they use burrows; their eggs are laid on the bare rock or in shallow depressions lined with plant material.

In Britain, northern fulmars historically bred on St. Kilda (where their harvesting for oil, feathers and meat was central to the islands' economy). They spread into northern Scotland in the 19th century, and to the rest of the United Kingdom by 1930. The expansion has continued further south; the fulmar can now often be seen in the English Channel and in France along the northern and western coasts, with breeding pairs or small colonies in Nord, Picardy, Normandy and along the Atlantic coast in Brittany.[10]

Feeding

Fulmars are highly pelagic outside the breeding season, like most tubenoses, feeding on fish, small squid, shrimp, crustaceans, marine worms, and carrion.[11] The range of these species increased greatly in the 20th century due to the availability of fish offal from commercial fleets, but may contract because of less food from this source and climatic change.[9] The population increase has been especially notable in the British Isles.[12]

Like other petrels, their walking ability is limited, but they are strong fliers, with a stiff wing action quite unlike the gulls. They look bull-necked compared to gulls, and have short stubby bills. They are long-lived, the longest recorded lifespan for F. glacialis being 40 years, 10 months and 16 days.[13]

Relationship with humans

Fulmars have for centuries been hunted for food. The engraver Thomas Bewick wrote in 1804 that "Pennant, speaking of those [birds] which breed on, or inhabit, the Isle of St Kilda, says—'No bird is of so much use to the islanders as this: the Fulmar supplies them with oil for their lamps, down for their beds, a delicacy for their tables, a balm for their wounds, and a medicine for their distempers.'"[14] A photograph by George Washington Wilson taken about 1886 shows a "view of the men and women of St Kilda on the beach dividing up the catch of Fulmar".[15] James Fisher, author of The Fulmar (1952) calculated that every person on St Kilda consumed over 100 fulmars each year; the meat was their staple food, and they caught around 12,000 birds annually.

Fulmar eggs were collected until the late 1920s in the St Kilda islands by their men scaling the cliffs. The eggs were buried in St Kilda peat ash to be eaten through the cold, northern winters. The eggs were considered to taste like duck eggs in taste and nourishment.[16]

However, when the human population left St Kilda in 1930, the fulmar population did not suddenly increase.[17]

Both the southern fulmar and the northern fulmar are listed as of Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).[18][19]

Gallery

Northern fulmar on the nest in Orkney, Scotland

Northern fulmar on the nest in Orkney, Scotland Southern fulmar in Drake's Passage

Southern fulmar in Drake's Passage Northern fulmar, breeding on Bear Island (Norway)

Northern fulmar, breeding on Bear Island (Norway)_flying%252C_side-on.jpg.webp)

Northern fulmar, breeding on Bear Island

Northern fulmar, breeding on Bear Island Northern fulmar, at the Norwegian bird-island Runde

Northern fulmar, at the Norwegian bird-island Runde Composite image of northern fulmars in different plumages

Composite image of northern fulmars in different plumages

References

- Stephens, James Francis (1826). Shaw, George (ed.). General Zoology, or Systematic Natural History. Vol. 13, Part 1. London: Kearsley et al. p. 236.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 166. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Gray, George Robert (1855). Catalogue of the Genera and Subgenera of Birds Contained in the British Museum. London: British Museum. p. 129.

- Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. pp. 60–61.

- Double, M. C. (2003)

- Ehrlich, Paul R. (1988)

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2021). "Petrels, albatrosses". IOC World Bird List Version 11.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- Howard, Hildegard (1984). "Additional Avian Records from the Miocene of Kern County, California with the Description of a New Species of Fulmar". Bull. Southern California Acad. Sci. 83 (2): 84–89. Archived from the original on 2014-07-15. Retrieved 2014-06-13.

- Maynard, B. J. (2003)

- Yeatman, L (1976)

- "Northern Fulmar". Audubon. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- Bull, J. & Farrand Jr., J. (1993)

- Robinson, R. A. (2005). "Fulmar Fulmarus glacialis". British Trust for Ornithology. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- Bewick, Thomas (1847). A History of British Birds, volume II, Water Birds (revised ed.). p. 226.

- Wilson, George Washington (1886). "Dividing the Catch of Fulmar St Kilda". GB 0231 MS 3792/C7187 6188. Aberdeen Library Special Collections and Museums. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- The Daily Mail April 18 1930: article by Susan Rachel Ferguson

- Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. London: Chatto and Windus. pp. 12–18. ISBN 978-0-7011-6907-7.

- BirdLife International (2018). "Fulmarus glacialis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22697866A132609419. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22697866A132609419.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- BirdLife International (2018). "Fulmarus glacialoides". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22697870A132609920. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22697870A132609920.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

Sources

- Bull, John; Farrand Jr., John (June 1993) [1977]. "Open Ocean". In Opper, Jane (ed.). The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds. The Audubon Society Field Guide Series. Vol. Birds (Eastern Region) (First ed.). New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 314. ISBN 0-394-41405-5.

- Double, M. C. (2003). "Procellariiformes (Tubenosed Seabirds)". In Hutchins, Michael; Jackson, Jerome A.; Bock, Walter J.; Olendorf, Donna (eds.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins. Joseph E. Trumpey, Chief Scientific Illustrator (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 107–111. ISBN 0-7876-5784-0.

- Ehrlich, Paul R.; Dobkin, David, S.; Wheye, Darryl (1988). The Birders Handbook (First ed.). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. p. 14. ISBN 0-671-65989-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Harrison, P. (1983). Seabirds: an identification guide. Beckenham, U.K.: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-7470-1410-8.

- Yeatman, L. (1976). Atlas des oiseaux nicheurs de France. Paris: Société Ornithologique de France. p. 8. See also more recent publication(s) with similar title.

Further reading

- Fisher, James (1952). The Fulmar. London: Collins.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Northern fulmar profile as part of BTO BirdFacts

- Explore Species: Northern Fulmar at eBird (Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

- Explore Species: Southern Fulmar at eBird (Cornell Lab of Ornithology)