Education in Italy

Education in Italy is compulsory from 6 to 16 years of age,[2] and is divided into five stages: kindergarten (scuola dell'infanzia), primary school (scuola primaria or scuola elementare), lower secondary school (scuola secondaria di primo grado or scuola media inferiore), upper secondary school (scuola secondaria di secondo grado or scuola media superiore) and university (università).[3] Education is free in Italy and free education is available to children of all nationalities who are residents in Italy. Italy has both a private and public education system.[4]

| |

| Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca | |

|---|---|

| Minister of Education and Merit | Giuseppe Valditara |

| National education budget (2016) | |

| Budget | €65 billion |

| General details | |

| Primary languages | Italian |

| System type | public |

| Compulsory primary education | 1859 |

| Literacy (2015) | |

| Total | 99.2%[1] |

| Post secondary | 386,000 |

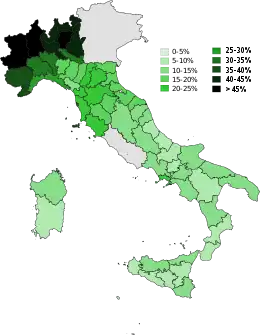

In 2018, the Italian secondary education was evaluated as below the OECD average.[5] Italy scored below the OECD average in reading and science, and near OECD average in mathematics. Mean performance in Italy declined in reading and science, and remained stable in mathematics.[5] Trento and Bolzano scored at an above the national average in reading.[5] Compared to school children in other OECD countries, children in Italy missed out on a greater amount of learning due to absences and indiscipline in classrooms.[6] A wide gap exists between northern schools, which perform near average, and schools in the South, that had much poorer results.[7] The 2018 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study ranks children in Italy 16th for reading. Compared to school children in other OECD countries, children in Italy missed out on a greater amount of learning due to absences and indiscipline in classrooms.[8]

Tertiary education in Italy is divided between public universities, private universities and the prestigious and selective superior graduate schools, such as the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. 33 Italian universities were ranked among the world's top 500 in 2019, the third-largest number in Europe after the United Kingdom and Germany.[9] Bologna University, founded in 1088, is the oldest university in continuous operation,[10] as well as one of the leading academic institutions in Italy and Europe.[11] The Bocconi University, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, LUISS, Polytechnic University of Turin, Polytechnic University of Milan, Sapienza University of Rome, and University of Milan are also ranked among the best in the world.[12]

History

In Italy a state school system or Education System has existed since 1859, when the Legge Casati (Casati Act) mandated educational responsibilities for the forthcoming Italian state (Italian unification took place in 1861). The Casati Act made primary education compulsory, and had the goal of increasing literacy. This law gave control of primary education to the single towns, of secondary education to the provinces, and the universities were managed by the State. Even with the Casati Act and compulsory education, in rural (and southern) areas children often were not sent to school (the rate of children enrolled in primary education would reach 90% only after 70 years) and the illiteracy rate (which was nearly 80% in 1861) took more than 50 years to halve.

The next important law concerning the Italian education system was the Gentile Reform. This act was issued in 1923, thus when Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party were in power. In fact, Giovanni Gentile was appointed the task of creating an education system deemed fit for the fascist system. The compulsory age of education was raised to 14 years, and was somewhat based on a ladder system: after the first five years of primary education, one could choose the 'Scuola media', which would give further access to the "liceo" and other secondary education, or the 'avviamento al lavoro' (work training), which was intended to give a quick entry into the low strates of the workforce. The reform enhanced the role of the Liceo Classico, created by the Casati Act in 1859 (and intended during the Fascist era as the peak of secondary education, with the goal of forming the future upper classes), and created the Technical, Commercial and Industrial institutes and the Liceo Scientifico. The Liceo Classico was the only secondary school that gave access to all types of higher education until 1968. The influence of Gentile's Italian idealism was great,[13] and he considered the Catholic religion to be the "foundation and crowning" of education. In 1962 the 'avviamento al lavoro' was abolished, and all children up to 14 years had to follow a single program, encompassing primary education (scuola elementare) and middle school (scuola media).

From 1962 to the present day, the main structure of Italian primary (and secondary) education remained largely unchanged, even if some modifications were made: a narrowing of the gap between males and females (through the merging of the two distinct programmes for technical education, and the optional introduction of mixed-gender gym classes), a change in the structure of secondary school (legge Berlinguer) and the creation of new licei, 'istituti tecnici' and 'istituti professionali', offering students a broader range of options.

In 1999, in accordance with the guidelines laid down by the Bologna Process, the Italian university system switched from the old system (vecchio ordinamento, which led to the traditional 5-year Laurea degree), to the new system (nuovo ordinamento). The nuovo ordinamento split the former Laurea into two tracks: the Laurea triennale (a three-year degree akin to the Bachelor's Degree), followed by the 2-year Laurea specialistica (Master's Degree), the latter renamed Laurea Magistrale in 2007. A credit system was established to quantify the amount of work needed by each course and exam (25 work hours = 1 credit), as well as enhance the possibility to change course of studies and facilitate the transfer of credits for further studies or go on exchange (e.g. Erasmus Programme) in another country. However, it is now established that there is just a five-year degree "Laurea Magistrale a Ciclo Unico" for programmes such as Law and a six-year degree for Medicine.

In 2019, Education minister Lorenzo Fioramonti announced that in 2020 Italy would become the first country in the world to make the study of climate change and sustainable development mandatory for students.[14]

Primary education

Primary school (scuola primaria, also known as scuola elementare), is commonly preceded by three years of non-compulsory nursery school (or kindergarten, asilo). Primary school lasts five years. Until middle school, the educational curriculum is the same for all pupils: although one can attend a private or state-funded school, the subjects studied are the same (with the exception of special schools for the blind or the hearing-impaired): the students are given a basic education in Italian, English, mathematics, natural sciences, history, geography, social studies, and physical education. Some schools also have Spanish or French, musical arts and visual arts.

Until 2004, pupils had to pass an exam to access middle school (scuola secondaria di primo grado), comprising the composition of a short essay in Italian, a written math test, and an oral test on the other subjects. The exam has been discontinued and pupils can now enter middle school directly.

Usually students start primary school at the age of 6, but students who are born between January and March and are still 5 years old can access primary school early; this is called primina and the students doing it are called anticipatari. For example, a student born in February 2002 can attend primary school with students born in 2001.

Secondary education

.jpg.webp)

Secondary education in Italy lasts 8 years and is divided into two stages: middle school (scuola secondaria di primo grado, also known as scuola media) and high school (scuola secondaria di secondo grado, also known as scuola superiore).[15] Middle school lasts three years (roughly from age 11 to 14), and high school lasts five years (roughly from age 14 to 19). Every tier involves an exam at the end of the final year, required to earn a degree and have access to further education. Both in middle school and high school, students stay in the classroom for most of the time (barring such classes as physical education, which most often takes place in the gym), so it is the teachers who have to move from one classroom to another during the day.

In the lower middle school pupils start school at 8:00 am and finish at 1:00 pm (they may start later; they have a five-hour daily schedule, excluding variations), while in high school they attend school 5 to 8 hours a day depending on the day of the week and on the rules of the school. Usually, there are no breaks between each class, but most schools have a recess that lasts 15 to 30 minutes halfway through. If students have to stay in school even after lunch, there's a longer break to let them eat and rest.

There are three types of high school, subsequently divided into further specialization. There are subjects taught in each of these, such as Italian, English, mathematics, history, but most subjects are peculiar to a particular type of course (i.e. ancient Greek in the Liceo Classico, business economics in the Istituto tecnico economico or scenography in the Liceo Artistico):

- Liceo (lyceum)

- The education received in a Liceo is mostly theoretical, with a specialization in a specific field of studies which can be:

- humanities and antiquity (liceo classico),

- mathematics and science (liceo scientifico),

- foreign languages (liceo linguistico),

- psychology and pedagogy (liceo delle scienze umane),

- social science (liceo economico-sociale),

- fine arts (liceo artistico).

- Also, some schools have special options with more hours for some subjects, some lessons taken in English, or some different courses (called indirizzi) like liceo scientifico has "indirizzo liceo scientifico" (or "indirizzo tradizionale"), with latin, or "indirizzo liceo scientifico-scienze applicate" where there's not latin, there is informatics.[16]

- Istituto tecnico (technical institute)

- The education given in an Istituto tecnico offers both a wide theoretical education and a specialization in a specific field of studies (e.g.: economy, administration, technology, tourism, agronomy), often integrated with a three/six months internship in a company, association or university, from the third to the fifth and last year of study.[17]

- Istituto professionale (professional institute)

- This type of school offers a form of secondary education oriented towards practical subjects (engineering, agriculture, gastronomy, technical assistance, handcrafts), and enables the students to start searching for a job as soon as they have completed their studies, sometimes sooner, as some schools offer a diploma after three years instead of five.

Any type of high school which lasts 5 years grants access to the final exam, called esame di maturità or esame di stato, that takes place every year between June and July and grants access to university.[18] This exam consists of an oral examination and written tests. Some of them, like the Italian one, are the same for each school, while others are different according to the type of school. For example, in the Liceo classico students have to translate a Latin or ancient Greek text; in the Liceo scientifico students have to solve mathematics or physics problems; and so on. An Italian student is usually 19 when they enter university.

Higher education

Italy has a large and international network of public or state-affiliated universities and schools offering degrees in higher education. State-run universities of Italy constitute the main percentage of tertiary education in Italy and are managed under the supervision of Italian's Ministry of Education.

Italian universities are among the oldest universities in the world; the University of Bologna (founded in 1088) notably, is the oldest one ever; also, University of Padua, founded in 1222, and University of Naples Federico II are the oldest universities in Europe.[19][20] Most universities in Italy are state-supported. 33 Italian universities were ranked among the world's top 500 in 2019, the third-largest number in Europe after the United Kingdom and Germany.[9]

There are also a number of Superior Graduate Schools (Grandes écoles)[21] or Scuola Superiore Universitaria, offer officially recognized titles, including the Diploma di Perfezionamento equivalent to a Doctorate, Dottorato di Ricerca i.e. Research Doctorate or Doctor Philosophiae i.e. PhD.[22] Some of them also organize courses Master's degree. There are three Superior Graduate Schools with "university status", three institutes with the status of Doctoral Colleges, which function at graduate and post-graduate level. Nine further schools are direct offshoots of the universities (i.e. do not have their own 'university status'). The first one is the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa (founded in 1810 by Napoleon as a branch of École Normale Supérieure), taking the model of organization from the famous École Normale Supérieure. These institutions are commonly referred to as "Schools of Excellence" (i.e. "Scuole di Eccellenza").[21][23]

Italy hosts a broad variety of universities, colleges and academies. Founded in 1088, the University of Bologna is likely the oldest in the world.[24] In 2009, the University of Bologna is, according to The Times, the only Italian college in the top 200 World Universities. Milan's Bocconi University has been ranked among the top 20 best business schools in the world by The Wall Street Journal international rankings, especially thanks to its M.B.A. program, which in 2007 placed it no. 17 in the world in terms of graduate recruitment preference by major multinational companies.[25] Bocconi was also ranked by Forbes as the best worldwide in the specific category Value for Money.[26] In May 2008, Bocconi overtook several traditionally top global business schools in the Financial Times Executive education ranking, reaching no. 5 in Europe and no. 15 in the world.[27]

Other top universities and polytechnics are the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Milan, the LUISS in Rome, the Polytechnic University of Turin, the Politecnico di Milano (which in 2011 was ranked as the 48th best technical university in the world by QS World University Rankings[28]), the University of Rome La Sapienza (which in 2005 was Europe's 33rd best university,[29] and ranks among Europe's 50 and the world's 150 best colleges[30] and in 2013, the Center for World University Rankings ranked the Sapienza University of Rome 62nd in the world and the top in Italy in its World University Rankings.[31]) and the University of Milan (whose research and teaching activities have developed over the years and have received important international recognition). This University is the only Italian member of the League of European Research Universities (LERU), a prestigious group of twenty research-intensive European Universities. It has also been awarded ranking positions such as 1st in Italy and 7th in Europe (The Leiden Ranking – Universiteit Leiden).

Summary

Compulsory education is highlighted in yellow.

| level | name | duration | certificate awarded | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-school education | Scuola dell'infanzia (nursery school) | 3 years (age: 3 to 6) | ||

| Primary education | Scuola primaria (primary school) | 5 years (age: 6 to 11) | Licenza di scuola elementare (until 2004)[32] | |

| Lower secondary education | Scuola secondaria di primo grado (first grade secondary school) | 3 years (age: 11 to 14) | Diploma di scuola secondaria di primo grado | |

| Upper secondary education | Scuola secondaria di secondo grado (second grade secondary school) | 5 years (age: 14 to 19) (compulsory until the age of 16, or until year 2) | Diploma di liceo Diploma di istituto tecnico Diploma di istituto professionale | |

| Formazione professionale (vocational education) (until 2010) | 3 or 5 years (age 14 to 17 or 14 to 19) (compulsory until the age of 16, or until year 2) | Qualifica professionale (3 years), Licenza professionale (5 years) | ||

| Higher education | Laurea (Bachelor's degree) Diploma accademico di primo livello | 3 years | ||

| Laurea magistrale (Master's degree) Diploma accademico di secondo livello | 2 years | |||

| Laurea magistrale a ciclo unico (Bachelor's + Master's degree) | 5 years only for: Farmacia (pharmacy) Chimica e tecnologie farmaceutiche (pharmaceutical chemistry) Medicina veterinaria (veterinary medicine) Giurisprudenza (law) Architettura (architecture) Ingegneria edile-Architettura (architectural engineering) Conservazione dei beni culturali (conservation of cultural properties) Scienze della formazione primaria (sciences of primary education), necessary for teaching in nursery or primary schools | |||

| 6 years, only for: Medicina e chirurgia (medicine and surgery) Odontoiatria e protesi dentaria (dentistry) | ||||

| Dottorato di ricerca (PhD) Diploma accademico di formazione alla ricerca Diploma di Perfezionamento – PhD (Superior Graduate Schools in Italy) | 3, 4 or 5 years | |||

Standards

In 2018, the Italian secondary education was evaluated as below the OECD average.[5] Italy scored below the OECD average in reading and science, and near OECD average in mathematics. Mean performance in Italy declined in reading and science, and remained stable in mathematics.[5] Trento and Bolzano scored at an above the national average in reading.[5] Compared to school children in other OECD countries, children in Italy missed out on a greater amount of learning due to absences and indiscipline in classrooms.[6] A wide gap exists between northern schools, which perform near average, and schools in the South, that had much poorer results.[7] The 2018 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study ranks children in Italy 16th for reading.

Compared to school children in other OECD countries, children in Italy missed out on a greater amount of learning due to absences and indiscipline in classrooms.[8]

See also

References

- "- Human Development Reports". hdr.undp.org.

- "comma 622". Camera.it. 2 December 2006. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- "- Human Development Reports" (PDF). hdr.undp.org.

- Bertola, Giuseppe; Checchi, Daniele; Oppedisano, Veruska (December 2007). "Private School Quality in Italy" (PDF). Discussion Paper Series. IZA Institute of Labor Economics (IZA DP No. 3222).

- "PISA 2018 results". www.oecd.org. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- "Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) Italy report" (PDF).

- "The literacy divide: territorial differences in the Italian education system" (PDF). Parthenope University of Naples. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- "Italy report" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Number of top-ranked universities by country in Europe". jakubmarian.com. 2019.

- Nuria Sanz, Sjur Bergan: "The heritage of European universities", 2nd edition, Higher Education Series No. 7, Council of Europe, 2006, , p. 136

- "Censis, la classifica delle università: Bologna ancora prima". 3 July 2017.

- "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2015". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. 2015. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- Moss, M. E. (2004). Mussolini's fascist philosopher: Giovanni Gentile reconsidered. New York: P. Lang.pp 26–73.

- "Italy to become first country to make learning about climate change compulsory for school students". CNN. 6 November 2019.

- "liceo". Corriere della Sera.

- "Microsoft Word - Allegato A definitivo 02012010.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- "LINEE GUIDA PER IL PASSAGGIO AL NUOVO ORDINAMENTO" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- "Esame di stato - Miur". Archived from the original on 1 March 2014.

- Kamp, Norbert. "Federico II di Svevia, Imperatore, Re di Sicilia e di Gerusalemme, Re dei Romani". Treccani. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Cenni Storici". Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Pagina di transizione". ricercaitaliana.it.

- "SITO IN MANUTENZIONE". www.istruzione.it.

- "Scuole – Scuole di Eccellenza". scuoledieccellenza.it.

- "Università di Bologna (oldest university in the world)". Virtual Globetrotting. 21 October 2006. Retrieved 27 October 2009.

- "Conferenze, ospiti, news ed eventi legati agli MBA della SDA Bocconi – MBA SDA Bocconi". SDA Bocconi. Archived from the original on 27 June 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "Gatech :: OIE :: GT Study Abroad Programs". Archived from the original on 8 May 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "Sda Bocconi supera London Business School – ViviMilano". Corriere della Sera. 12 November 2008. Archived from the original on 24 September 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "Politecnico di Milano – QS World University Rankings". topuniversities.com. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- "Top 100 European Universities". Arwu.org. Archived from the original on 30 April 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2009.

- "ARWU2008". Arwu.org. Archived from the original on 22 August 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2009.

- "World University Rankings 2013". Center for World University Rankings. 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- "Archivio Corriere della Sera". Corriere della Sera.

Further reading

- Anastasiou, Dimitris, James M. Kauffman, and Santo Di Nuovo. "Inclusive education in Italy: description and reflections on full inclusion." European Journal of Special Needs Education 30.4 (2015): 429-443, regarding students with disabilities

- Begeny, John C., and Brian K. Martens. "Inclusionary education in Italy: A literature review and call for more empirical research." Remedial and Special education 28.2 (2007): 80-94, regarding students with disabilities.

- Biemmi, Irene. "Gender in schools and culture: taking stock of education in Italy." Gender and Education 27.7 (2015): 812-827.

- Checchi, Daniele. "University education in Italy." International Journal of Manpower (2000) online.

- D’Alessio, Simona. Inclusive education in Italy (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

- Eid, Luca, Nicola Lovecchio, and Marco Bussetti. "Physical and sport education in Italy." Journal of Physical Education & Health-Social Perspective 1.2 (2012): 37-41. online

- Fabbris, Luigi. Effectiveness of University Education in Italy (Physica-Verlag Heidelberg, 2007).

- Luzzatto, Giunio. "Higher Education in Italy 1985-95: an overview." 'European Journal of Education 31.3 (1996): 371-378. online

- Mortari, Luigina, and Roberta Silva. "Teacher Education in Italy." in Teacher Education in the Global Era (Springer, Singapore, 2020) pp. 115-132.

- Musatti, Tullia, and Mariacristina Picchio. "Early education in Italy: Research and practice." International Journal of Early Childhood 42.2 (2010): 141-153. online

- Montgomery, Walter A. Education in Italy (1919) online

- Passow, A. Harry et al. The National Case Study: An Empirical Comparative Study of Twenty-One Educational Systems. (1976) online

- Todeschini, Marco Enrico. "Teacher Education in Italy: New Trends." Studies on Higher Education (2003): 223+. online

- Türk, Umut. "Socio-economic determinants of student mobility and inequality of access to higher education in Italy." Networks and Spatial Economics 19.1 (2019): 125-148 online.

Historical

- Benadusi, Luciano. "The Attempts at Reform of Secondary Education in Italy." European Journal of Education (1988): 229-236 online.

- Black, Robert. Humanism and education in medieval and Renaissance Italy: tradition and innovation in Latin schools from the twelfth to the fifteenth century (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

- Bozzano, Monica, Gabriele Cappelli, and Michelangelo Vasta. "Whither education? The long shadow of pre-unification school systems into Italy's Liberal Age (1861-1911)." (2022). online

- Cappelli, Gabriele. "One size that didn’t fit all? Electoral franchise, fiscal capacity and the rise of mass schooling across Italy’s provinces, 1870–1911." Cliometrica 10.3 (2016): 311-343. online

- Cappelli, Gabriele, and Michelangelo Vasta. "A 'Silent Revolution': school reforms and Italy’s educational gender gap in the Liberal Age (1861–1921)." Cliometrica 15.1 (2021): 203-229. online

- Cappelli, Gabriele, and Gloria Quiroga Valle. "Female teachers and the rise of primary education in Italy and Spain, 1861–1921: evidence from a new dataset." Economic History Review 74.3 (2021): 754-783. online

- Ciccarelli, Carlo, and Jacob Weisdorf. "Pioneering into the past: Regional literacy developments in Italy before Italy." European Review of Economic History 23.3 (2019): 329-364. online

- Deplano, Valeria. "Making Italians: colonial history and the graduate education system from the liberal era to Fascism." Journal of Modern Italian Studies 18.5 (2013): 580-598.

- Hohnerlein, Eva Maria. "Development and diffusion of early childhood education in Italy: Reflections on the role of the church from a historical perspective (1830–2010)." in The Development of Early Childhood Education in Europe and North America (Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2015) pp. 71–91.

- Lazzini, Arianna, Giuseppina Iacoviello, and Rosella Ferraris Franceschi. "Evolution of accounting education in Italy, 1890–1935." Accounting History 23.1-2 (2018): 44-70 online.

- Minio-Paluello, L. Education In Fascist Italy (1946) online

- Sani, Roberto. "Honest Citizens and Good Christians: Don Bosco and Salesian Education in the 150-year History of United Italy." in Honest Citizens and Good Christians: Don Bosco and Salesian Education in the 150-year History of United Italy (2011): 477-489. online

External links

- Information on education in Italy, OECD – Contains indicators and information about Italy and how it compares to other OECD and non-OECD countries

- Diagram of Italian education system, OECD – Using 1997 ISCED classification of programmes and typical ages. Also in Italian