Cryptocurrency wallet

A cryptocurrency wallet is a device,[1] physical medium,[2] program or a service which stores the public and/or private keys[3] for cryptocurrency transactions. In addition to this basic function of storing the keys, a cryptocurrency wallet more often offers the functionality of encrypting and/or signing information. Signing can for example result in executing a smart contract, a cryptocurrency transaction (see "bitcoin transaction" image), identification, or legally signing a 'document' (see "application form" image).[4]

History

In 2008 bitcoin was introduced as the first cryptocurrency following the principle outlined by Satoshi Nakamoto in the paper “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.”[5] The project was described as an electronic payment system using cryptographic proof instead of trust. It also mentioned using cryptographic proof to verify and record transactions on a blockchain.[6]

Technology

Private and public key generation

A cryptocurrency wallet works by a theoretical or random number being generated and used with a length that depends on the algorithm size of the cryptocurrency's technology requirements. The number is converted to a private key using the specific requirements of the cryptocurrency cryptography algorithm requirement. A public key is then generated from the private key using whichever cryptographic algorithm is required. The private key is used by the owner to access and send cryptocurrency and is private to the owner, whereas the public key is to be shared to any third party to receive cryptocurrency.[7]

Up to this stage no computer or electronic device is required and all key pairs can be mathematically derived and written down by hand. The private key and public key pair (known as an address) are not known by the blockchain or anyone else. The blockchain will only record the transaction of the public address when cryptocurrency is sent to it, thus recording in the blockchain ledger the transaction of the public address.

Duplicate private keys

Collision (two or more wallets having the same private key) is theoretically possible, since keys can be generated without being used for transactions, and are therefore offline until recorded in the blockchain ledger. However, this possibility is effectively negated because the theoretical probability of two or more private keys being the same is extremely low. The number of possible wallets and thus private keys is extremely high,[8][9] so duplicating or hacking a certain key would be inconceivable.[10][11]

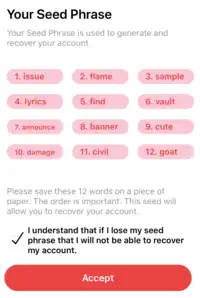

Seed phrases

In modern convention a seed phrase is now utilised which is a random 12 to 24 (or even greater) list of dictionary words which is an unencrypted form of the private key. (Words are easier to memorize than numerals). When online, exchange and hardware wallets are generated using random numbers, and the user is asked to supply a seed phrase. If the wallet is misplaced, damaged or compromised, the seed phrase can be used to re-access the wallet and associated keys and cryptocurrency in toto.[12]

Wallets

A number of technologies known as wallets exist that store the key value pair of private and public key known as wallets. A wallet hosts the details of the key pair making cryptocurrency transactions possible. Multiple methods exist for storing keys or seeds in a wallet.[13]

A brainwallet or brain wallet is a type of wallet in which one memorizes a passcode (a private key or seed phrase).[14][15] Brainwallets may be attractive due to plausible deniability or protection against governmental seizure,[16] but are vulnerable to password guessing (especially large-scale offline guessing).[14][16] Several hundred brainwallets exist on the Bitcoin blockchain, but most of them have been drained, sometimes repeatedly.[14]

Crypto wallets vis-à-vis DApp browsers

DApp browsers are specialized software that supports decentralized applications. DApp browsers are considered to be the browsers of Web3 and are the gateway to access the decentralized applications which are based on blockchain technology. That means all DApp browsers must have a unique code system to unify all the different codes of the DApps.

While crypto wallets are focused on the exchange, purchase, sale of digital assets and support narrowly targeted applications, the browsers support different kinds of applications of various formats, including exchange, games, NFTs marketplaces, etc.

Characteristics

In addition to the basic function of storing the keys, a cryptocurrency wallet may also have one or more of the following characteristics.

Simple cryptocurrency wallet

A simple cryptocurrency wallet contains pairs of public and private cryptographic keys. The keys can be used to track ownership, receipt or spend cryptocurrencies.[17] A public key allows others to make payments to the address derived from it, whereas a private key enables the spending of cryptocurrency from that address.[18]

The cryptocurrency itself is not in the wallet. In the case of bitcoin and cryptocurrencies derived from it, the cryptocurrency is decentrally stored and maintained in a publicly available distributed ledger called the blockchain.[17]

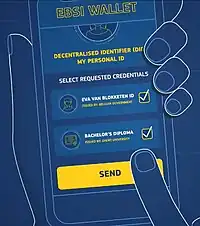

eID wallet

Some wallets are specifically designed to be compatible with a framework. The European Union is creating an eIDAS compatible European Self-Sovereign Identity Framework (ESSIF) which runs on the European Blockchain Services Infrastructure (EBSI). The EBSI wallet is designed to (securely) provide information, an eID and to sign 'transactions'.[4]

Multisignature wallet

In contrast to simple cryptocurrency wallets requiring just one party to sign a transaction, multi-sig wallets require multiple parties to sign a transaction.[19] Multisignature wallets are designed for increased security.[20] Usually, a multisignature algorithm produces a joint signature that is more compact than a collection of distinct signatures from all users.[21]

Smart contract

In the cryptocurrency space, smart contracts are digitally signed in the same way a cryptocurrency transaction is signed. The signing keys are held in a cryptocurrency wallet.

Sequential deterministic wallet

A sequential deterministic wallet utilizes a simple method of generating addresses from a known starting string or "seed". This would utilize a cryptographic hash function, e.g. SHA-256 (seed + n), where n is an ASCII-coded number that starts from 1 and increments as additional keys are needed.[22]

Hierarchical deterministic wallet

The hierarchical deterministic (HD) wallet was publicly described in BIP32.[23] As a deterministic wallet, it also derives keys from a single master root seed, but instead of having a single "chain" of keypairs, an HD wallet supports multiple key pair chains.

This allows a single key string to be used to generate an entire tree of key pairs with a stratified structure.[24]

BIP39 proposed the use of a set of human-readable words to derive the master private key of a wallet. This mnemonic phrase allows for easier wallet backup and recovery, due to all the keys of a wallet being derivable from a single plaintext string.

Non-deterministic wallet

In a non-deterministic wallet, each key is randomly generated on its own accord, and they are not seeded from a common key. Therefore, any backups of the wallet must store each and every single private key used as an address, as well as a buffer of 100 or so future keys that may have already been given out as addresses but not received payments yet.[25][17]: 94

Concerns

When choosing a wallet, the owner must keep in mind who is supposed to have access to (a copy of) the private keys and thus potentially has signing capabilities. In case of cryptocurrency the user needs to trust the provider to keep the cryptocurrency safe, just like with a bank. Trust was misplaced in the case of the Mt. Gox exchange, which 'lost' most of their clients' bitcoins. Downloading a cryptocurrency wallet from a wallet provider to a computer or phone does not automatically mean that the owner is the only one who has a copy of the private keys.

A wallet can also have known or unknown vulnerabilities. A supply chain attack or side-channel attack are ways of introducing vulnerabilities. In extreme cases even a computer which is not connected to any network can be hacked.[26]

See also

References

- Roberts, Daniel (15 December 2017). "How to send bitcoin to a hardware wallet". Yahoo! Finance.

- Divine, John (1 February 2019). "What's the Best Bitcoin Wallet?". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Newman, Lily Hay (2017-11-05). "How to Keep Your Bitcoin Safe and Secure". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- "European Blockchain Services Infrastructure (EBSI)". 2020-12-31. Archived from the original on 2022-10-19.

- Nakamoto, Satoshi. "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System" (PDF).

- "What are blockchain and cryptocurrency?", Blockchain and Cryptocurrency: International Legal and Regulatory Challenges, Bloomsbury Professional, 2022, doi:10.5040/9781526521682.chapter-002, ISBN 978-1-5265-2165-1, retrieved 2023-02-26

- Baloian, Artiom (2021-12-18). "How To Generate Public and Private Keys for the Blockchain". Medium. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- Singer, David; Singer, Ari (2018). "Big Numbers: The Role Played by Mathematics in Internet Commerce" (PDF).

- Kraft, James S. (2018). An introduction to number theory with cryptography. Lawrence C. Washington (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL. ISBN 978-1-315-16100-6. OCLC 1023861398.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Yadav, Nagendra Singh & Goar, Vishal & Kuri, Manoj. (2020). Crypto Wallet: A Perfect Combination with Blockchain and Security Solution for Banking. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation. 24. 6056-6066. 10.37200/IJPR/V24I2/PR2021078.

- Guler, Sevil (2015). "Secure Bitcoin Wallet" (PDF). UNIVERSITY OF TARTU FACULTY OF MATHEMATICS AND COMPUTER SCIENCE Institute of Computer Science Computer Science Curriculum: 48 – via core.ac.uk.

- Shaik, Cheman. (2020). Securing Cryptocurrency Wallet Seed Phrase Digitally with Blind Key Encryption. International Journal on Cryptography and Information Security. 10. 1-10. 10.5121/ijcis.2020.10401.

- Jokić, Stevo & Cvetković, Aleksandar Sandro & Adamović, Saša & Ristić, Nenad & Spalević, Petar. (2019). Comparative analysis of cryptocurrency wallets vs traditional wallets. Ekonomika. 65. 10.5937/ekonomika1903065J.

- Vasek, Marie; Bonneau, Joseph; Castellucci, Ryan; Keith, Cameron; Moore, Tyler (2017). "The Bitcoin Brain Drain: Examining the Use and Abuse of Bitcoin Brain Wallets" (PDF). In Grossklags, Jens; Preneel, Bart (eds.). Financial Cryptography and Data Security. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 9603. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 609–618. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-54970-4_36. ISBN 978-3-662-54970-4.

- Kent, Peter; Bain, Tyler (2022). Bitcoin For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-119-60213-2.

- Castellucci, Ryan. "Cracking Cryptocurrency Brainwallets" (PDF). rya.nc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Antonopoulos, Andreas (12 July 2017). Mastering Bitcoin: Programming the Open Blockchain. O'Reilly Media, Inc. ISBN 9781491954386. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- "Bitcoin Wallets: What You Need to Know About the Hardware". The Daily Dot. 2018-11-20. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- "Bitcoin Startup Predicts Cryptocurrency Market Will Grow By $100 Billion in 2018". Fortune. Archived from the original on 2020-12-04. Retrieved 2019-02-15.

- Graham, Luke (2017-07-20). "$32 million worth of digital currency ether stolen by hackers". www.cnbc.com. Retrieved 2019-02-15.

- Bellare, Mihir; Neven, Gregory (2006). "Identity-Based Multi-signatures from RSA". Topics in Cryptology – CT-RSA 2007. pp. 145–162. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.207.2329. doi:10.1007/11967668_10. ISBN 978-3-540-69327-7.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Oranburg, Seth C., ed. (2022), "Cryptographic Theory and Decentralized Finance", A History of Financial Technology and Regulation: From American Incorporation to Cryptocurrency and Crowdfunding, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 112–128, doi:10.1017/9781316597736.010, ISBN 978-1-107-15340-0, retrieved 2023-02-26

- "Bip32". University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- Gutoski, Gus; Stebila, Douglas. "Hierarchical deterministic Bitcoin wallets that tolerate key leakage" (PDF). iacr.org. International Association for Cryptologic Research. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- Acharya, Vivek (30 June 2021). "How Ethereum Non-Deterministic and Deterministic Wallets Work". Oracle Corporation. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- Air-gap jumpers on cyber.bgu.ac.il