Bobasatrania

Bobasatrania is an extinct genus of prehistoric bony fish that survived the Permian-Triassic extinction event. Fossils of Bobasatrania were found in beds of Changhsingian (late Permian) to Ladinian (Middle Triassic) age.[1] It was most speciose during the Early Triassic.[2]

| Bobasatrania Temporal range: ~ | |

|---|---|

| |

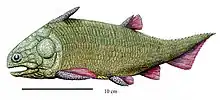

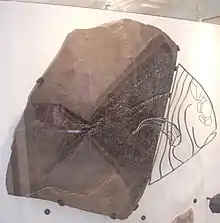

| Bobasatrania canadensis fossil | |

| |

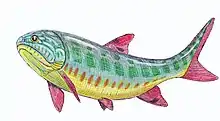

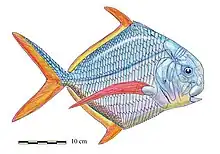

| Bobasatrania canadensis restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | †Bobasatrania White, 1932 |

| Type species | |

| †Bobasatrania mahavavica White, 1932 | |

| Other species | |

| Synonyms | |

The genus was named after the locality Bobasatrana (near Ambilobe) in northeast Madagascar, from where the type species, Bobasatrania mahavavica, was described. The name of this species refers to the Mahavavy River.[3]

Occurrence

Bobasatrania probably originated during the Lopingian (late Permian) epoch, survived the Permian-Triassic extinction event, and underwent a speciation event during the Triassic in the shallow coastal waters off the Pangaean supercontinent. Their fossils are therefore found across the globe (Canada, France, Germany, Greenland, Italy, Madagascar, Spitsbergen, Pakistan, Switzerland, United States).[1][4][5] Some of the best examples are known from the Wapiti Lake region of British Columbia, Canada.[6] The geologically oldest fossils are from the Wordie Creek Formation of Greenland. Fossils include complete specimens but also isolated, characteristic tooth plates.[1]

Appearance

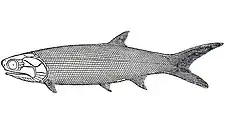

They have a distinctive diamond-shaped body, forked tail and long thin pectoral fins. B. ceresiensis was about 25 cm (9.8 in) long,[7] while other species, such as B. canadensis, grew to about 1.2 m (3.9 ft) in length or larger.[8][9] The structure of their teeth (tooth plates) suggests they fed on shelled animals.

References

- Böttcher, Ronald (2014). "Phyllodont tooth plates of Bobasatrania scutata (Gervais, 1852) (Actinoperygii, Bobasatraniiformes) from the Middle Triassic (Longobardian) Grenzbonebed of southern Germany and eastern France, with an overview of Triassic and Palaeozoic phyllodont tooth plates". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 274 (2–3): 291–311. doi:10.1127/njgpa/2014/0454.

- Romano, Carlo; Koot, Martha B.; Kogan, Ilja; Brayard, Arnaud; Minikh, Alla V.; Brinkmann, Winand; Bucher, Hugo; Kriwet, Jürgen (February 2016). "Permian-Triassic Osteichthyes (bony fishes): diversity dynamics and body size evolution". Biological Reviews. 91 (1): 106–147. doi:10.1111/brv.12161. PMID 25431138. S2CID 5332637.

- White, Errol Ivor (1932). "On a new Triassic Fish from North-East Madagascar". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. Series 10. 10 (55): 80–83. doi:10.1080/00222933208673541.

- Nielsen, Eigil. (1952). "A preliminary note on Bobasatrania groenlandica" (PDF). Meddelelser Fra Dansk Geologisk Forening. 12 (2): 197–204.

- Bürgin, Toni (1992). "Basal ray-finned fishes (Osteichthyes; Actinopterygii) from the Middle Triassic of Monte San Giorgio (Canton Tessin, Switzerland)". Schweizerische Paläontologische Abhandlungen. 114: 1–164..

- "Past lives: Chronicles of Canadian Paleontology - Triassic fishing". Archived from the original on 2009-12-21. Retrieved 2009-11-13. Past Lives: Chronicles of Canadian Paleontology

- Rieppel, Olivier (2019). Mesozoic Sea Dragons: Triassic Marine Life from the Ancient Tropical Lagoon of Monte San Giorgio. Indiana University Press. p. 116. doi:10.2307/j.ctvd58t86. ISBN 978-0253040114. S2CID 241534158.

- Russell, Loris S. (1951). "Bobasatrania? canadensis (Lambe), a giant chondrostean fish from the Rocky Mountains". Annual Report of the National Museum of Canada, Bulletin. 123: 218–224.

- Neuman, Andrew G. (2015). "Fishes from the Lower Triassic portion of the Sulphur Mountain Formation in Alberta, Canada: geological context and taxonomic composition". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 52 (8): 557–568. Bibcode:2015CaJES..52..557N. doi:10.1139/cjes-2014-0165.

Further reading

- Nielsen, Eigil. 1942. Studies on Triasslc Fishes from East Greenland. I. Glaucolepis and Boreosomus. Palaeozoologica Groenlandica. vol. I.

- Nielsen, Eigil. 1949. Studies on Triassic Fishes from East Greenland. II. Australosomus and Birgeria. Palaeozoologica Groenlandica. vol. III. 204 Medd, fra Dansk Geol. Forening. København. Bd. 12. [1952].

- Stensiö, E. A:EON, 1921. Triassic Fishes from Spitsbergen. Part I. Vienna.

- Stensiö, E. 1932. Triassic Fishes from East Greenland. Medd. om Grønland, Bd. 83, Nr. 3.

- Stensiö, E. 1947. The sensory Lines and dermal Bones of the Cheek in Fishes and Amphibians. Stockholm, Kungl. Sv. Vet. Akad. Handl., ser. 3, Bd. 22, no. 1.

- Watson, D . M. S., 1928. On some Points in the Structure of Palaeonlscid and allied Fish. London, Zool. Soc. Proc, pt. 1.