Åland War

The Åland War[lower-alpha 1] was the operations of a British-French naval force against military and civilian facilities on the coast of the Grand Duchy of Finland in 1854–1856, during the Crimean War between the Russian Empire and the allied France and Britain. The war is named after the Battle of Bomarsund in Åland. Although the name of the war refers to Åland, skirmishes were also fought in other coastal towns of Finland in the Gulf of Bothnia and the Gulf of Finland.

| Åland War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Crimean War | |||||||

A sketch of the quarter deck of HMS Bulldog in Bomarsund, Edwin T. Dolby, 1854 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

The Russian Empire, advancing on the Romanian front, had provoked the Ottoman Empire to declare war on 4 October, 1853, and Britain and France decided to support the Ottomans. The purpose of the Åland War was to sever Russia's service routes and foreign trade and force it to sue for peace, and to involve Sweden in the war against Russia.[1] The blockade was to be carried out in such a way as to render the Russian navy in the Baltic Sea inoperable by destroying the coastal defensive forts, the navy and the trade warehouses which served as foreign trade depots. A significant part of the damage was caused to Finland, as a large part of the merchant fleet flying the Russian flag at that time was in Finland, an autonomous Grand Duchy under the Russian crown since 1809.

The war had a major impact on the subsequent demilitarization of Åland.

Beginning of the war

The British Navy Division, which consisted of nine steam-powered ships, four older also steam-powered second-line ships, four frigates, and several smaller paddle-wheel vessels, left Spithead for the Baltic Sea on 11 March 1854 under the command of Vice Admiral Sir Charles Napier. French troops were commanded by General Achille Baraguey d'Hilliers,[2] while a detachment of the French Navy was under the command of Vice Admiral Alexandre Parseval-Deschenes.[3] However, the war was not declared to begin until 27 March. The British-French naval division of one hundred ships and boats was, by the standards at the time, quite modern with its steam-powered vessels, and it succeeded in bottling up the Russian fleet. The Russian Navy fought defensively, keeping close to the protection of sea forts. The majority of the Allied fleet's activities were directed against the Grand Duchy of Finland. The first Victoria Crosses of all time were awarded to sailors of the British-French Baltic Navy.[4]

In June, the threat of the British-French navy had already been identified as necessitating the re-establishment of a standing army based on the allotment system similar to one that existed when Finland was still part of Sweden. Interim Governor-General Platon Rokassowski gave his consent.[5] At the beginning of the war, the army in the Grand Duchy of Finland consisted only of a Guards Regiment, a naval captain and a battalion of grenadiers. Due to the antiquity of its fleet, Russia was not able to resist effectively, but considered its ships as a platform for their cannons as additional protection for war ports such as Viapori (now Suomenlinna) and Kronstadt. There was already a reserve army in Finland in 1855 to supplement the permanent army of nine battalions.

The course of the war

Battle in Åland

A British-French naval division besieged and captured the unfinished Bomarsund fortress on Åland in the late summer of 1854. The fort was blown up in early September. Because the range of the ship's cannons was longer than that of the coastal cannons, the ships were able to destroy the sea fortress without the latter being able to respond effectively outside the range of its guns.[1]

Battles in Gulf of Bothnia

Rear-Admiral Sir James Hanway Plumridge sailed in the Navy Division, which included HMS Leopard, HMS Valorous, HMS Vulture and HMS Odin, to the Gulf of Bothnia with the task of destroying munitions found in stockpiles. In the Gulf of Bothnia, warfare extended to all coastal towns between 1854 and 1855, with the most significant skirmishes being seen in Rauma, Oulu, Raahe, Tornio and Kokkola. Plumbridgre had authorized Captain George Giffard of HMS Leopard to secure the closure of the Gulf of Bothnia. The British War Minister, the Duke of Newcastle, had asked to avoid destroying defenceless cities. Giffard's own initiative in the matter did not lead to action on the part of Admiral Plumridge. The devastation in Raahe caused a debate in the British House of Commons. The Quakers demanded fundraising to compensate for the damage. Kveekarintie ("Quakers road") in Raahe was built with compensation money.[6]

From Nystad to Björneborg

The actions of the enemy, who sailed in the Gulf of Bothnia, extended to Nystad (Swedish name is used instead of the Finnish in modern use Uusikaupunki) in June 1855, when the British corvette Harrier entered its waters. The captain of the ship sent a letter to the magistrate warning that the town would be bombed if soldiers came there. Russian troops commanded by Colonel Engelhard were then stationed seven kilometres from Uusikaupunki. At the same time, the British captured a Luvian galeas from the port and burned 14 other merchant vessels. On 6 July however, an optical telegraph operating in the town was bombarded when the town was unable to deliver the fresh meat the navy demanded. A few residents were killed and small fires broke out near the telegraph station.[7]

A British warship entered the port of Rauma on 2 July 1855. Mayor Pettersson negotiated with the British, but refused to hand over the ships they demanded. The enemy then landed with five boats and about a hundred men, starting to occupy the harbour. The British set fire to the warehouse buildings and ships, but had to withdraw after fire was opened by Russian Cossacks who defended the port and a civilian guard made up of townspeople. According to Swedish newspapers, the English lost seven soldiers dead and two injured in the skirmish. The British reported six injured, two of whom later died. During the battle, the British managed to set fire to one schooner and two galeases. After the withdrawal of the landing force, a warship anchored in front of the port began firing on the town of Rauma. During the 2,5-hour artillery fire, at least 200 shots were counted, but they did not wreak much havoc.[8] The British version of the course of events was different from that of the Rauma people. Commodore A. H. Gardner claimed to have been deceived by Mayor Pettersson because he had imagined that his demands had been granted. Gardner's chief Commodore Warden, on the other hand, stated in a report to Vice Admiral James Dundas that the skirmish that caused the casualties was due to a misunderstanding and a lack of common language among the negotiators. Mayor Pettersson was also outraged by the incident and made his own complaint to Russian War Minister Vasily Dolgorukov, who in turn forwarded it as a French translation to Admiral Dundas and the British Admiralty.[8] The British and French retaliation followed three weeks later on 24 July, when two enemy warships anchored in front of the port of Rauma. The next day, ships began firing on the town and at the same time a number of sailors landed, setting fire to port buildings and timber depots. Rockets and bombs were fired into the urban area until 11 p.m., but they did not wreak havoc either. In the port, on the other hand, a total of 54 buildings and a large amount of timber for shipbuilding were destroyed. The people of Rauma tried to respond to the firing with handguns, but the firing distance was too great and the bullets only hit the sides of the ships.[8]

The town of Björneborg (Pori in Finnish) was the target of hostilities for the first time in the late summer of 1854, when an enemy struck the city's outer port on Reposaari and destroyed the mast of an optical telegraph erected there. In addition, property and livestock were taken from local residents. The enemy did not approach the city centre for the first time until a year later, on 9 August 1855. The British warship Tartar, commanded by Commodore Hugh Dunlop, had sailed from Säppi Island to Reposaari two days earlier. There were a small number of Russian soldiers in Pori at the time, as well as a group of about 70 volunteers, but Claes Adam Wahlberg, the Mayor of Pori, decided, after consulting with the local burghers, to give up the fight. The reason was that almost the whole of Pori had been destroyed by a major fire three years earlier, and there was no desire to endanger the partially rebuilt city.[9] The cannons placed on Luotsinmäki were rolled into the river and Mayor Wahlberg set out to negotiate with the enemy who had invaded the city along the Kokemäki River. He reached an agreement according to which Pori will be saved from destruction when the enemy is handed over to the city-owned paddle-wheel steamer Sovinto and a dozen other ships in the river port, which had been taken for protection just over ten kilometres upstream of the Kokemäenjoki River to Haistila. The activities of the people of Pori were considered shameful and according to some information, Lieutenant General Alexander Jakob von Wendt would have later demoted the officer who had retreated from Luotsinmäki to sergeant during a review held at the Pori market square.[9]

From Kristinestad to Nykarleby

At the beginning of the war, a battalion of soldiers and two artillery batteries were stationed to protect Kristinestad. The military detachment left the town in the spring of 1855, taking with it the rifles given to a group of civilian volunteers. At the same time, the cannons were also pulled out of their positions and hidden. On 27 June the British paddle steamers Firefly and Driver sailed in front of Kristinestad, destroying empty artillery emplacements and threatening to shell the town, the port's large timber depot and shipyard. As a result of the negotiations, the shelling was avoided, but in return the British received the schooner Pallas and food supplies. Firefly returned to top up its food stores in mid-July, when the French warship D’Assas was also involved. After that, the enemy no longer visited Kristinestad.[10]

In the first summer of 1854, Vasa was spared destruction by the English, perhaps because the channels leading to the harbours were difficult to navigate and the English knew of the destruction of the city by fire two years earlier. In the autumn of 1855, on 3 August, the corvette Firelly anchored in front of the port of Palosaari. An empty house owned by G. G. Wolff, a trade counsellor near the harbour, was burned down as the English had heard that it had housed Russian soldiers. Wolff's ship Fides was seized and another newly completed ship was burned. In addition, the English took over Grönberg's Preciosa as well as two brigs. The English also decided to replenish their tar stores, and the previously seized schooner Necken was towed to port. However, the loading was interrupted as the Russian detachment sent to the scene arrived to defend the port. The corvette retreated beyond gunnery range and anchored near Fjällskär. The naval attack on the port of Palosaari took place on 8 August with two cannon-armed longboats, and the events of the attack are part of the legend of Vaasa's civil warfare:

"One longboat fired at Mansikkasaari with both cannons and fire-rockets and ignited a few buildings. The other positioned itself between Hietasaari and the mainland, from where it fired at both Mansikkasaari and Palosaari. When the barrage began, two companies of the Vaasa Battalion were ordered to the shore. The companies stationed themselves in Palosaari Harbour and on the shore opposite Hietasaari, and the sharpshooters were able to dislodge the longboats with their fire. Eliel Malmberg, a non-commissioned officer, was specially commended for the operation. He and some twenty other sharpshooters climbed on the roof of the Palosaari packing warehouse, where they were able to fire effectively at the enemy. Once the firing began, the governor had immediately asked the Vaasa detachment to send reinforcements to the town. A Russian half-battery arrived at forced pace from Kokkola under the command of a hard-drinking captain. The Vaasa residents offered drinks to the gunners who had come to the rescue, with the exception of the drunken captain, who was left without at the orders the governor. The captain was also kept aside when guns commenced firing. However, in the absence of skilled command, the salvos did not produce results, so the drunken captain had to be called up. He immediately contrived to score a bullseye."[11]

The next day, 9 August, the English corvette set sail, towing two seized vessels. The port itself had suffered only minor damage, and other losses were minor. One Russian and one Finnish soldier were killed. The funeral with military honours of the Finnish signalman took place the next day at Kappelinmäki, with the residents of the city participating.

Nykarleby was completely spared the war, even though enemy ships visited the city's outer harbour. The captains of the ships seized by the British provided incorrect information about the artillery batteries placed at the mouth of the Lapua River flowing through the city and the number of military units stationed in the locality, which apparently led the enemy not to attack.[12]

From Jakobstad to Tornio

The enemy ships had been moving on Jakobstad for the first time already in July 1854, but due to the removed channel buoys they could not reach the port. The next time warships were seen was in July 1854, when Captain H. C. Otter of Firefly and Captain Gardner of Driver visited the city's inner harbour. They negotiated with Gabriel Tengström, the Mayor of Jakobstad, who managed to convince them that there was no crown property in Jakobstad. In addition, the mayor's defiant behaviour led the English to believe that similar resistance could be expected as in Kokkola. Tartar, commanded by Hugh Dunlop, arrived off Jakobstad in November, seizing one merchant ship and also attempting to land on Tukkisaari. However, a Russian artillery battery forced the boats used by the landing force to return to their mother ship. On 13–14 November, Jakobstad was fired upon for a couple of hours, but the projectiles did not cause any damage.[13]

HMS Vulture and HMS Odin, commanded by Frederick Glasse, arrived off Kokkola on 7 June 1854, when Glasse demanded the delivery of the ships and material in the port. In what is known as Skirmish of Halkokari, a detachment sent ashore from the ships was repulsed by citizens of Kokkola armed by trade councillor Anders Donner.[14][15] Before the British came to Vaasa, two Russian companies had come to the rescue.[16] The British tried to land in Kokkola again the following year. HMS Tartar and HMS Porcupine launched seven landing boats, but the attack was repulsed without material damage after the Davidsberg skirmish.

The squadron destroyed ships and tar stores in Raahe on 30 May 1854 and in Oulu on 1 June. In Raahe, the English landed unhindered with six sloops armed with howitzers and eight smaller boats. They burned thirteen ships under construction, a tar court and a pitch burner under the control of the Oulu Trade Association. In addition, the British burned construction timber, planks, salt, firewood and e.g. 7,000 barrels of tar. This came back to bite them after the war, as the tar burned had been ordered and paid for by English merchants.[17] The last time the British visited Oulu was on 3 June when they demanded firewood, threatening to burn the entire city. Although all cargo boats were sunk, 12 cords were transported in tar boats to the English. After 4 June they were divided into two flotillas sailing for Tornio and Kokkola. The Oulu local government estimated that the burning and seizure of goods caused the city and its citizens damages in the amount of 380,969 rubles and 98 kopecks. The value of the ships was estimated at 170,925 rubles, the amount of tar of 16,460 barrels at 40,150 rubles, the burnt magazines at 22,950 rubles, the value of the shipyards at 13,500 rubles and the ship timber and supplies at 11,495 rubles. The greatest damage in Oulu was suffered by G. Bergbom, who lost his property in the amount of 101,106 rubles, of which the loss of the trading premises of G. & C. Bergbom Ab amounted to 24,600 rubles. A total of 53 people suffered losses in Oulu, but only nine people lost more than 10,000 rubles.

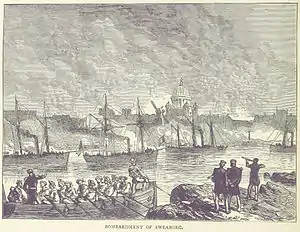

Battles in Gulf of Finland

In the Gulf of Finland, the naval squadron bombarded Suomenlinna, (Sveaborg in Swedish), for two days, and the people of Helsinki watched the events from the shore. Finnish naval troops manned coastal batteries on Santahamina. The British Navy also fired rockets at Suomenlinna, and this was reportedly the first time these were used in warfare in Finland (one rocket is on display at the War Museum in Helsinki).[18] The Svartholm fortress south of Loviisa was bombarded.[19] The Ruotsinsalmi sea fortress, built in Kymi (now Kotka) and left without defenders, was almost completely destroyed in the war.[20]

Ending of the war

For the third summer, the British planned to assemble a larger fleet in the Baltic Sea, with more than 250 ships, but the Crimean War ended before there was time to do so. As a result of the end of the Crimean War, the Åland War ended with the British demolishing the Bomarsund Fortress, which had first been offered to Sweden as a reward for remaining neutral in fear of Russia's future reactions. For the British and French, the Bomarsund Fortress was a symbol of Russian expansionism threatening the security of the Swedish capital, Stockholm, during the Crimean War. Offering the fortress to Sweden and then destroying it was evidence of Britain's ability to buffer Russia's supposed enlargement efforts.

The British demanded in the Paris Peace Treaty of 1856 that Russia keep Åland unfortified and neutralized. The demilitarization of Åland continued even after the First World War, when Åland was finally confirmed to belong to Finland by a decision of the League of Nations on the basis of historical documents. The reason was that it was also ruled from Turku, not Stockholm, during the Swedish rule of the Grand Duchy of Finland, which included eight then Swedish provinces. In return for the confirmation that the area belonged to Finland, Finland had to guarantee the Ålanders' extensive self-government and cultural rights. Demilitarization continued even after that. The fortification of Åland came to the fore in later negotiations in 1938–1939, in which the Soviet Union sought to protect its own Baltic Sea areas from possible German attacks. Even after the Second World War, Åland remained a demilitarized region.

The experience of the Crimean War in Russia began with a spirit of reform, during which Czar Alexander II carried out major social reforms to modernize and industrialize Russia.

The Oolannin sota song

On the basis of the Åland War, the Finnish song "Oolannin sota" was born in the 1850s, the lyricist or composer of which is unknown. The "fästninki" mentioned in the words of the song means the fortress of Bomarsund in Sund, Åland.[21]

The song is very popular, but its origin was unknown for a long time, until researchers Jerker Örjans and Pirjo-Liisa Niinimäki found out in the 21st century. The original version of the song "Åland War Song" was found in a handwritten songbook in the municipality of Renko in the 1850s. The original words were apparently composed by unknown Bomarsund soldiers who remained prisoners of war in England, as the words tell of prisoners of war in Lewes, England. Örjans and Niinimäki speculate that the lyricist may have been Johan Wallenius from Tavastia, who worked as a surgeon in Bomarsund. The original wording depicted a rather realistically defeated struggle and was apparently transformed into its now known form in the early 20th century, which does not mention Bomarsund's surrender. The current lyrics are known to first appear in a songbook published in 1911. The original language of the song is obviously Finnish, as the earliest known Swedish version dates back to 1925. In Åland itself, the song is still completely unknown today.[22][23][24]

Sources

References

- Suomalaiset linnoitukset, SKS. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. 2011. ISBN 978-952-222-275-6.

- Nordisk familjebok (1913), s. 435 (in Swedish)

- Johnsson & Malmberg 2013, s. 125, 131–133, 154, 217–219. (in Finnish)

- Ashcroft (2006), preface.

- Theodor Westrin & Ruben Gustafsson Berg: Nordisk familjebok konversationslexikon och realencyklopedi. Nordisk familjeboks förlag, 1916. (in Swedish)

- Ja se Oolannin sota – Raahen Museo (in Finnish)

- Auvinen, s. 195–204 (in Finnish)

- Auvinen, s. 212–219. (in Finnish)

- Auvinen, s. 235–244. (in Finnish)

- Auvinen, s. 204–209 (in Finnish)

- http://lipas.uwasa.fi/~itv/publicat/kriminsota.htm (in Finnish)

- Auvinen, s. 209–212

- Auvinen, s. 245–253 (in Finnish)

- Facta2001, WSOY 1981, 5. osa, palsta 437 (in Finnish)

- Facta2001, WSOY 1981, 3. osa, palsta 593 (in Finnish)

- Oiva Turpeinen: Oolannin sota – Itämainen sota Suomessa'. Tammi, 2003. (in Finnish)

- "Oolannin sota Oulussa". Niilo Naakan tarinat (in Finnish). Pohjois-Pohjanmaan museo. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- Sotamuseota nuuskimassa - Sveaborg-Viapori -projekti (in Finnish)

- History of War against Russia

- /alltypes.asp?d_type=5&menu_id=1098# www.kotka.fi - linnoitushistoria (in Finnish)

- National Anthems & Patriotic Songs – Oolannin sota lyrics + English translation

- syntyi engelsmannin vankeudessa Turun Sanomat 15.2.2004. (in Finnish)

- Oolannin sota – Suosittu laulu ja alkuperäinen ”Ålandin sota laulu” Bomarsundssällskapet. (in Swedish)

- Tutun laulurallatuksen alkuperäisversio antaa kovin erilaisen kuvan Oolannin sodasta – lue sanat Yle 12.6.2013. (in Finnish)

Literature

- Eero Auvinen: Krimin sota, Venäjä ja suomalaiset. Turun yliopisto, 2015. (in Finnish)

- Raoul Johnson & Ilkka Malmberg: Kauhia Oolannin sota – Krimin sota Suomessa 1854–1855. John Nurmisen säätiö, 2013. ISBN 978-952-9745-31-9. (in Finnish)

- Väinö Wallin: Itämainen sota Suomessa. WSOY, 1905. (in Finnish)

External links

- Åland History – Visit Åland Archived 2020-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Bomarsund was big at the time Åland belonged to Russia – Visit Åland

- Biography: John Bythesea VC Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine