Amur Annexation

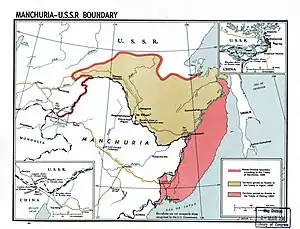

The Amur Annexation was the annexation of territories adjoining the Amur River by the Russian Empire in 1858–1860 through unequal treaties forced upon the Chinese Qing dynasty. The 1858 Treaty of Aigun signed between the Russian general Muraviev and the Chinese official Yishan ceded Priamurye, a territory stretching from the Amur River in the south to the Stanovoy Mountains in the north, but the Qing government refused to recognize the validity of the treaty at the time. Two years later, the Second Opium War concluded with the Convention of Peking, which affirmed Russian gains under the Treaty of Aigun and China also ceded Primorye, a territory that included the entire Pacific coast down to the Korean border, as well as the island of Sakhalin. These territories roughly correspond to modern-day Amur Oblast and Primorsky Krai, respectively. Collectively, they are often referred to as Outer Manchuria, part of the greater region of Manchuria.[1]

Background

| Part of a series on the |

| History of China |

|---|

| History of Russia |

|---|

|

|

|

Hydrologically, the Stanovoy Range separates the rivers that flow north into the Arctic from those that flow south into the Amur River. Ecologically, the area is the southeastern edge of the Siberian boreal forest with some areas good for agriculture along the middle Amur. Socially and politically, from about 600 CE, it was the northern fringe of the Chinese-Korean-Manchu world.[2]

In 1643, Russian adventurers spilled over the Stanovoys. By 1689, they were driven back by the Manchus. By the Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689) the two empires recognized the Stanovoys and the Argun River as their border. This remained stable until the 1840s.[2]

Following the voyages of Captain James Cook, significant numbers of British, French, and American vessels began entering the Pacific. They were followed by Russians like Grigory Shelikhov and Nikolai Rezanov who were mainly concerned with the new Russian colonies in Alaska. This raised the problem of naval defense of the east coast of Siberia and the possibility of using the Amur River as a supply route to the Pacific.[2]

Muravyov and the Treaty of Aigun (1858)

In 1845, Alexander von Middendorf entered the Amur country and wrote a report. In 1847, Aleksandr Gavrilov reached the mouth of the Amur but could not find a deep-water entrance.[3]

In 1847, Nikolay Muravyov was appointed governor-general of East Siberia. Before leaving for Irkutsk, he arranged for the creation of an Amur Committee to coordinate work in the area. In 1849, he made an overland trip to Okhotsk and then to Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. One result of this was the removal of the main naval center from Okhotsk to Petropavlovsk.[4]

In 1848, Gennady Nevelskoy was sent in the Baikal to explore the Pacific coast.

In 1849, Nevelskoy sailed part way up the Amur, and then sailed south through the Tatar Strait, thereby proving that Sakhalin was an island, a fact that was kept a military secret.

In 1850, Nevelskoy founded Nikolayevsk-on-Amur on what was alleged Chinese territory. Karl Nesselrode, the foreign minister, tried to overrule this, but Nicholas I declared "where once the Russian flag is raised, it must not be lowered". Over the next three years, Nevelskoy established other forts on the alleged Chinese territory around the mouth of the Amur.

To establish a military force, Muravyov created a new Cossack host, the Transbaikalian Cossacks, by arming 20,000 mining serfs. In May–June 1854 he and 1,000 men sailed down the Amur to Nikolayevsk. The Manchu governor at Aigun had no choice but to let them pass.[4]

News of the Crimean War reached the far east in July 1854. In September, an Anglo-French naval force was defeated at the Siege of Petropavlovsk. Judging that Petropavlovsk could not be defended, Muravyov ordered Rear Admiral Vasily Zavoyko to move his forces to the Amur area. In May 1855, Charles Elliot's force found Zavoyko at De Kastri Bay (south of Cape Nevelskoy on the Tatar Strait).

Under the cover of fog, Zavoiko withdrew north to the mouth of the Amur, which baffled the British since they thought that Sakhalin was connected to the mainland. In 1855, Muravyov sent a 3,000-man force down the Amur, including settlers. The Chinese declared this to be illegal, but did nothing.

Also in 1855, Russia and Japan signed the Treaty of Shimoda which temporarily resolved their conflict in Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands. The Russian representative was Admiral Putyatin (see below).

The Second Opium War broke out in 1856. In 1858, the British and French captured Canton. When news of this reached Saint Petersburg, the foreign minister, Alexander Gorchakov, who had replaced Nesselrode, decided that it was time to "activate Russian Far Eastern Policy". Muravyov was given plenipotentiary powers and Admiral Yevfimy Putyatin was sent to Beijing to negotiate a more favorable relation.[4]

In 1856 and 1857, Muravyov sent more settlers down the Amur. In 1858, he went himself. His instructions were not to use force except to rescue captives. On reaching Aigun he presented the local governor with a treaty, which was signed. The Treaty of Aigun assigned all the land north of the Amur to Russia and declared the area east of the Ussuri River and south of the Amur (northern Primorye) to be a Russo-Chinese condominium until further negotiations.[4] The Qing government initially refused to ratify the Treaty of Aigun and considered the treaty invalid, but the Russian gains under the Treaty of Aigun was affirmed as part of the 1860 Sino-Russian Convention of Peking.[5]

Muravyov continued down the Amur and founded Khabarovsk at the mouth of the Ussuri. In September 1858, Alexander II promoted him to full general and granted him the suffix '-Amursky'. In 1859, he sent an exploring expedition down the coast as far as Vladivostok.[6]

Putyatin, Ignatyev, and the Convention of Peking (1860)

Meanwhile, Admiral Yevfimy Putyatin was travelling overland to China. Reaching Kyakhta, he was refused entry in the spring of 1857. He sailed down the Amur and took his ship to Tientsin. Refused entry again, he joined the British and French at Shanghai. When the allies took the Taku Forts Putyatin offered himself as a mediator. The result was the Treaties of Tientsin which granted most of the allied demands. Without fully informing the allies, Putyatin made a separate deal with the Chinese on June 13, 1858.[7]

In return for cannon, 20,000 rifles and military instructors, the frontier would be adjusted in some unspecified way. Putyatin was not aware of the Treaty of Aigun which had been signed 16 days earlier. After the allies withdrew the Chinese failed to implement the treaties. The allies returned in June 1859, attempted to retake the Taku Forts and failed. As a result, the Chinese refused to ratify the treaties.[7]

At this point, a 27-year-old Major General named Nikolay Pavlovich Ignatyev entered the picture. In March 1859 he was assigned to accompany the Russian weapons and instructors. At the frontier he found that the Chinese had rejected the treaties and would not accept the weapons. He continued to Beijing where he stayed at the Russian ecclesiastical mission and attempted to negotiate with the Manchus.[8]

Hearing of allied preparations, Ignatyev joined the British and French in Shanghai and proved to be helpful to the allied councils, as he had a map of Beijing and good interpreters. By October 1860 the British and French had retaken the Taku forts. They entered Beijing and the Emperor fled to Rehe. Ignatyev placed himself as an intermediary between the Europeans and Chinese. In the first two Treaties of Peking (October 24 and 25, 1860) nearly all the allied demands were met. Ignatyev continued negotiations for a Russo-Chinese treaty. He convinced the Chinese that only his support would cause the allies to leave the capital.[8]

The result was the Russo-Chinese Convention of Peking of November 14, 1860. By this, the Treaty of Tientsin was ratified and all the land north of the Amur and east of the Ussuri was ceded to the Russian Empire. Thus, by pure diplomacy and only a few thousand troops, the Russians took advantage of Chinese weakness and the strength of the other European powers to annex 350,000 square miles (910,000 km2) of Chinese territory. With the exception of Muravyov's rather ceremonial cannonade at Aigun, they had apparently not fired a single shot.[8]

See also

References

- G. Patrick March, Eastern Destiny: Russia in Asia and the North Pacific (Greenwood, 1996).

- R. A. Pierce, Eastward to Empire: Exploration and Conquest on the Russian Open Frontier, to 1750 (Montreal, 1973).

- James R. Gibson, "Russia on the Pacific: the role of the Amur." Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien 12.1 (1968): 15-27.

- Rosemary K. I. Quested, The Expansion of Russia in East Asia, 1857-1860 (1968)

- Elleman, Bruce (2019). International Rivalry and Secret Diplomacy in East Asia, 1896-1950. Taylor & Francis. p. 19. ISBN 9781317328155.

- Mark Bassin, Imperial visions: nationalist imagination and geographical expansion in the Russian Far East, 1840–1865 (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

- Henry McAleavy, "China and the Amur Provinces" History Today (1964), Vol. 14 Issue 6, pp 381-390.

- John L. Evans, Russian Expansion on the Amur, 1848-1860: the Push to the Pacific (Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 1999).

Bibliography

- Bassin, Mark. "Inventing Siberia: visions of the Russian East in the early nineteenth century." American Historical Review 96.3 (1991): 763–794. online

- Bassin, Mark. Imperial visions: nationalist imagination and geographical expansion in the Russian Far East, 1840–1865 (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

- Cheng, Tien-Fong. A History Of Sino-Russian Relations (1957) pp 11–38,

- Gibson, James R. "The Significance of Siberia to Tsarist Russia." Canadian Slavonic Papers 14.3 (1972): 442–453.

- McAleavy, Henry. "China and the Amur Provinces" History Today (1964) 14#6 pp 381–390.

- March, G. Patrick. "Eastern Destiny: Russia in Asia and the North Pacific" (1996)