Health care in Australia

Health care in Australia operates under a shared public-private model underpinned by the Medicare system, the national single-payer funding model. State and territory governments operate public health facilities where eligible patients receive care free of charge. Primary health services, such as GP clinics, are privately owned in most situations, but attract Medicare rebates. Australian citizens, permanent residents, and some visitors and visa holders are eligible for health services under the Medicare system. Individuals are encouraged through tax surcharges to purchase health insurance to cover services offered in the private sector, and further fund health care.

In 1999, the Howard government introduced the private health insurance rebate scheme, under which the government contributed up to 30% of the private health insurance premium of people covered by Medicare. Including these rebates, Medicare is the major component of the total Commonwealth health budget, taking up about 43% of the total. The program was estimated to cost $18.3 billion in 2007–08.[1] In 2009 before means testing was introduced, the private health insurance rebate was estimated to cost $4 billion, around 20% of the total budget.[2] The overall figure was projected to rise by almost 4% annually in real terms in 2007.[1] In 2013–14 Medicare expenditure was $19 billion and expected to reach $23.6 billion in 2016/7.[3] In 2017–18, total health spending was $185.4 billion, equating to $7,485 per person, an increase of 1.2%, which was lower than the decade average of 3.9%. The majority of health spending went on hospitals (40%) and primary health care (34%). Health spending accounted for 10% of overall economic activity.[4]

State and territory governments (through agencies such as Queensland Health) regulate and administer the major elements of healthcare such as doctors, public hospitals and ambulance services. The federal Minister for Health sets national health policy and may attach conditions to funding provided to state and territory governments. The funding model for healthcare in Australia has seen political polarisation, with governments being crucial in shaping national healthcare policy.[5]

In 2013, the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) was commenced. This provides a national platform to individuals with disability to gain access to funding. The NDIS aims to provide resources to support individuals with disabilities in terms of medical management as well as social support to assist them in pursuing their dreams, careers, and hobbies. The NDIS also has supports for family members to aid them in taking care of their loved ones and avoid issues like carer burnout. Unfortunately, the National Disability Insurance Scheme is not without its limitations but overall the system is standardised across Australia and has helped many people with disabilities improve their quality of life.[6]

Statistics

In 2005/2006 Australia had (on average) 1 doctor per 322 people and 1 hospital bed per 244 people.[7] At the 2011 Australian Census 70,200 medical practitioners (including doctors and specialist medical practitioners) and 257,200 nurses were recorded as currently working.[8] In 2012, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare recorded data showing a rate of 374 medical practitioners per 100,000 population. The same study reported a rate of 1,124 nurses and midwives per 100,000 population.[9]

Along with many countries around the world, there is a shortage of health professionals in Australia despite growth in the health workforce in previous years. From the years 2006–2011 the health workforce employment rate increased by 22.1%, which is reflected in the increase from 956,150 to 1,167,633.[9]

In a sample of 13 developed countries, Australia was eighth in its population weighted usage of medication in 14 classes in 2009 and also in 2013. The drugs studied were selected on the basis that the conditions treated had high incidence, prevalence and/or mortality, caused significant long-term morbidity and incurred high levels of expenditure and significant developments in prevention or treatment had been made in the last 10 years. The study noted considerable difficulties in cross-border comparison of medication use.[10]

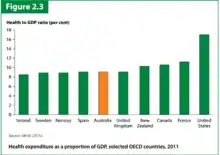

Australia's health-expenditure–to–GDP ratio (~9.5%) in 2011–12 was slightly above average compared with other OECD countries.[11]

Medicare and the universal health care system

Medicare is the main funding source for health services in Australia and the universal health care system. "Medicare" can be broken down into four distinct programs, each run by Services Australia:[12]

- the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS), which is the namesake program that subsidises a portion of each 'episode' of a health service

- the National Health Reform Agreement (NHRA), which covers the cost of treatment in state and territory facilities, such as hospitals, by sharing the cost between the Australian Government and state and territory government

- the Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule (PBS) which assists with the costs of some medicines and therapies

- and My Aged Care (MAC), which provides contributions towards the cost of aged care services.

Medicare contributions to health services are only made for Australian citizens and permanent residents. Some visitors and visa holders are also entitled to Medicare coverage, although cover for international visitors under Reciprocal Health Care Agreements is limited to immediately necessary care only.[13][14]

To be eligible for on-the-spot Medicare coverage, patients generally have to present their Medicare card at the time. Funding for Medicare is raised by a 2% Medicare levy, as well as a Medicare levy surcharge for people over 35 that don't have private health insurance. Exemptions and reductions are available for low-income earners.[15] Both the MBS and PBS also have "safety nets" which further cover the cost of health care and medicines for people that pay a lot out-of-pocket each year.

Medicare does not cover the cost of ambulance services, most dental care, glasses, contact lenses or hearing aides, and cosmetic surgery. Most of these are covered under private health insurance, or by state and territory governments.[16]

Medicare Benefits Schedule

The Medicare Benefits Schedule lists all services that they will contribute towards, how much a standard cost for that service is (called the schedule Fee), and what percentage of that fee that Medicare will cover. Around 90% of general practitioners "bulk bill" consultations, which means they will only charge how much Medicare will cover for eligible patients.[12] The MBS also contributes partially towards hospital admissions, with the rest being covered by either a NHRA payment (for public hospitals) or private health insurance (for either public or private hospitals).[16]

Health care providers may individually decide how much to charge, and may charge more than the scheduled fee.[17] Families or individuals are also subject to the safety net threshold: after a certain amount of out-of-pocket expenses in a calendar year, Medicare will increase the contribution percentage for specialist services.[18] Certain concession holders, such as veterans, those with disabilities, and low-income earners receiving payments from Centrelink, often can claim a higher percentage of the scheduled fee than what the general population can.[18]

Other universal health services like the cancer screening programs and the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) are covered under separate agreements between the different levels of government. There are also other programs within the broad Medicare system that support access to mental health services (Better Access Scheme), care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, and rural and remote people.[19][20][21][22]

National Health Reform Agreement

Public hospitals and community health services are owned and operated by state and territory health departments, and jointly funded by the Australian Government and the state and territory government. These include local public health units, but exclude Primary Health Networks (which are funded directly by the federal government). Additional costs to public health services relating to the COVID-19 pandemic receive additional contributions under the National Partnership Agreement on COVID-19 Response (NPA).

NHRA funding is a mix of two systems: block funding and activity-based funding. Block funding is specific to each hospital, and is used to cover the cost of teaching and research, and for most rural and remote health facilities. Activity-based funding (ABF) is used for larger hospitals, where they receive a certain amount of money for 'episode of care' they provide, depending on what care is provided.[23]

The National Health Funding Pool Administrator (the Administrator), through the National Health Funding Body (NHFB), oversees the National Health Funding Pool (NHFP) which is a lump-sum account of all government spending on health care. The Administrator uses information from the Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority (IHACPA) to distribute those funds to the local health networks that operate public hospitals.[24]

Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme

Under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, some prescription medications are subsidised by the Australian Government. The PBS does not cover the full cost of medications, and doesn't cover all medications either. People with certain concession cards, or that spend a lot on medicine, can also receive further rebates.[25]

Health insurance

Funding of the health system in Australia is a combination of government funding and private health insurance. Government funding is through the Medicare scheme, which subsidises out-of-hospital medical treatment and funds free treatment in a public hospital.

In Australia, health insurance is provided by a number of health insurance organisations, called health funds. Such insurance is optional, and covers the cost of treatment as a private patient in a hospital, and may provide “extras” cover.

- Hospital cover. Medicare covers the cost of treatment as a public patient at a public hospital for elective treatments as well as emergency or medically necessary treatments. A public patient is a person whose treatment is covered by Medicare, while a private patient is one whose hospital accommodation is covered entirely by either a health fund or by the patient themselves (self-funding). While Medicare does not make any contribution towards hospital accommodation fees, theatres fees or prostheses for privately admitted patients, it does pay a portion of all medical fees (fees charged by doctors) associated with a private admission. There are a number of community objections to being a public patient in a public hospital, including the lack of choice of doctors or carers, long waiting lists, etc., and many people who take out health insurance do so to be treated as a private patient in either a public hospital or a private hospital. A private patient in a public hospital is entitled to a doctor of their choice, and cover for accommodation in a ward, and theatre fees for surgery. A person without insurance cover must resort to being a public patient at a public hospital or else carry the cost alone.

- Extras cover. Some non-medical or allied health services are not covered by Medicare or by standard health insurance, such as dentistry, medical devices and alternative medicine. A person may in addition or as an alternative take out “extras” cover for such treatments. What services are covered and how much is reimbursed and caps that apply vary between funds.

Health insurance in Australia is community rated; health funds cannot take age, gender, pre-existing conditions or other underlying risk factors into account in the calculation of premiums.

The largest health fund with a 26.9% market share is Medibank. Medibank was set up to provide competition to private "for-profit" health funds. Although formerly government-owned, the fund operated as a government business enterprise from 2009 until it was privatised in 2014, operating as a fully commercialized business paying tax and dividends under the same regulatory regime as do all other registered private health funds. Medibank was privatised in 2014 and became for-profit. Australian health funds can be either 'for profit' including Bupa and nib; 'mutual' including Australian Unity; or 'non-profit' including GMHBA, HCF Health Insurance and CBHS Health Fund. Some have membership restricted to particular groups, some focus on specific regions – like HBF Health Fund which centres on Western Australia, but the majority have open membership. Almost all health funds that are not-for-profit or part of a member-owned group, regional or community based (26 insurers covering a combined +5 million lives) are part the Members Health Fund Alliance[26][27] Membership to most of these funds is also accessible using a comparison websites or the decision assistance sites. These sites operate on a commission-basis agreement with their participating health funds and allow consumers to compare policies before joining online.

Most aspects of health insurance in Australia are regulated by the Private Health Insurance Act 2007. Complaints and reporting of the health industry is carried out by an independent government agency, the Private Health Insurance Ombudsman.[28] The ombudsman publishes an annual report that outlines the number and nature of complaints per health fund compared to their market share.[29]

The private health system in Australia operates on a "community rating" basis, whereby premiums do not vary solely because of a person's previous medical history, current state of health, or (generally speaking) their age (but see Lifetime Health Cover loading below).[30] Balancing this are waiting periods, in particular for pre-existing conditions (usually referred to within the industry as PEA, which stands for "pre-existing ailment"). Funds are entitled to impose a waiting period of up to 12 months on benefits for any medical condition the signs and symptoms of which existed during the six months ending on the day the person first took out insurance. They are also entitled to impose a 12-month waiting period for benefits for treatment relating to an obstetric condition, and a 2-month waiting period for all other benefits when a person first takes out private insurance.[30]

Funds have the discretion to reduce or remove such waiting periods in individual cases. They are also free not to impose them, to begin with, but this would place such a fund at risk of "adverse selection", attracting a disproportionate number of members from other funds, or from the pool of intending members who might otherwise have joined other funds. It would also attract people with existing medical conditions, who might not otherwise have taken out insurance at all because of the denial of benefits for 12 months due to the PEA Rule. The benefits paid out for these conditions would create pressure on premiums for all the fund's members, causing some to drop their membership, which would lead to further rises, and a vicious cycle would ensue.

Health funds are not permitted to discriminate between members in terms of premiums, benefits or membership on the basis of racial origin, religion, sex, sexual orientation, nature of employment, and leisure activities. Premiums for a fund's product that is sold in more than one state can vary from state to state, but not within the same state.

Incentives

A number of incentives encourage people to take out and maintain private hospital insurance, including:

- Lifetime Health Cover loading: If a person has not taken out private hospital cover by 1 July after their 31st birthday, then when (and if) they do so after this time, their premiums must include a loading of 2% per annum. Thus, a person taking out private cover for the first time at age 40 will pay a 20% loading. The loading continues for 10 years. The loading applies only to premiums for hospital cover, not to ancillary (extras) cover.

- Medicare levy surcharge (MLS): People whose income for MLS purposes is greater than a specified amount and who do not have an 'appropriate level of cover'[31] (being a complying health insurance policy that provides hospital cover with a payable excess not more than $750 for a policy covering a single insured, or $1500 for a policy covering more than one insured) pay the MLS in addition to the standard Medicare levy.

- Private health insurance rebate: The government subsidises the premiums for all health insurance cover, including hospital and ancillary (extras), by a different percentage depending on income tier (with individuals on higher incomes entitled to a smaller rebate), and age (with those 70+ receiving the highest percentage rebate).

Medicare levy surcharge

The government encourages individuals with income above a set level to privately insure. This is done by charging these (higher income) individuals a surcharge of 1% to 1.5% of income if they do not take out health insurance, and a means-tested rebate. This is to encourage individuals who are perceived as able to afford private insurance not to resort to the public health system,[32] even though people with valid private health insurance may still elect to use the public system if they wish.

The Howard Coalition government introduced a Medicare levy surcharge (MLS) with effect from 1 July 1997, as an incentive for people on higher incomes to take out and maintain an appropriate level of private health insurance,[31] as part of an effort to reduce demand pressure on public hospitals by encouraging people to have insurance cover for them to use private hospitals.[33] Individuals can take out health insurance to cover out-of-pocket costs, with either a plan that covers just selected services, to a full coverage plan. In practice, a person with health insurance may still be left with out-of-pocket payments, as services in private hospitals often cost more than the insurance payment.

Initially, MLS of 1% applied to individuals and families who did not have an “appropriate level of cover“ and whose taxable income was above a prescribed threshold. In 1997, the MLS threshold was $90,000 for individuals or $180,000 for families.[34] The threshold increased by $1,500 for each dependent child after the first in the family group.

Since 1 July 2012, the basis of the threshold has been "income for MLS purposes", which includes the individual's or family group's taxable income, fringe benefits, superannuation contributions and net investment losses.

In 2014, the surcharge rate was increased from 1% to 1.25% for those with MLS income over $105,000, from $97,000, and 1.5% for those on incomes over $140,000, from $130,000; and the threshold amounts are doubled for families.

The MLS is calculated at the surcharge rate on the whole of an individual's MLS income, and not just the amount above the MLS threshold. The minimum MLS amount is $900.

The requirement that a higher-income earner have an “appropriate level of private hospital cover” is satisfied under the government's new four-tier hospital insurance structure introduced in 2019 by a basic hospital insurance cover. Extras or add-on insurance alone does not qualify.

Private health insurance rebate

In 1999, the Howard government introduced the private health insurance rebate scheme, under which the government contributed up to 30% of the private health insurance premium of people covered by Medicare. The program was estimated to cost $18.3 billion in 2007–08.[1] In 2009, before means testing was introduced, the private health insurance rebate was estimated to cost $4 billion, around 20% of the total budget.[2] The overall figure was projected to rise by almost 4% annually in real terms in 2007.[1]

Since 2009, the rebate has been income- and age-tested. For a single person whose "income for MLS purposes" is less than $90,000 a year, or $180,000 for a family, and under 65 years old, the rebate is 24.608% (1 April 2022 to 31 March 2023), covering both hospital and extras cover. The rebate phases down over those amounts and cuts out at $140,000 for a single person, and double for a family.[35] The rebate can be claimed as a premium reduction or as a refundable tax offset.[36]

Debates regarding Medicare focus on the two-tier system and the role of private health insurance. Controversial issues include:

- whether people with means should take up private health insurance

- whether rebates/incentives should be given in terms of private health insurance

- people with health insurance still accessing the tax-payer funded public system rather than relying on their insurance

- people with private health insurance are not required to pay the Medicare Levy Surcharge.[33]

Critics argue that the rebate is an unfair subsidy to those who can afford health insurance, claiming the money would be better spent on public hospitals where it would benefit everyone. Supporters argue that people must be encouraged into the private health care system, claiming the public system is not universally sustainable for the future. Similarly, even after the introduction of the rebate, some private health insurance companies have raised their premiums most years,[37] to an extent negating the benefit of the rebate.

In 2013/14 Medicare expenditure was $19 billion and expected to reach $23.6 billion in 2016/17.[38] During FY2014, approximately 47.2%[39] of Australians had private health insurance with some form of hospital cover.

Lifetime Health Cover loading

To arrest the decline in the number of Australians maintaining private health insurance, the government introduced the Lifetime Health Cover loading, under which people who take out private hospital insurance later in life pay higher premiums, called a “loading”, compared to those who have held coverage since they were younger, and may also be subject to the Medicare levy surcharge.

Four tier system

From 1 April 2019, the federal government introduced a four tiered system of private hospital insurance, under which health funds will classify hospital policies into four tiers – basic, bronze, silver and gold. Minimum coverage requirements will apply to each tier, and insurers can also offer add-ons (called "plus options") for the basic, bronze and silver tiers. The system will be rolled out by 1 April 2020.[40] Research conducted by consumer advocacy group Choice found silver plus options offered by some health funds cost more than rival funds’ gold options, while providing less coverage.[41]

Government agencies

Federal government agencies

Services Australia, formerly the Department of Human Services, is responsible for administering Australia's universal health insurance scheme, such as making payments to health providers or patients. The Department of Health and Aged Care is responsible for national regulation of medicines and therapeutic devices, with the Australian Border Force responsible for screening imports into Australia to make sure that only approved medicines are allowed across the border.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) is Australia's national agency for health and welfare statistics and information. Its biennial publication Australia's Health is a key national information resource in the area of health care. The Institute publishes over 140 reports each year on various aspects of Australia's health and welfare. Food Standards Australia New Zealand and the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency also play a role in protecting and improving the health of Australians.[42]

The Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (Ahpra) are responsible for regulating the registration of most health practitioners. Unless a person is registered on the National Register as a certain health practitioner, it is illegal to call themselves as such or provide health care. National Boards set the professional practice standards for each profession, and can apply to state and territory tribunals to suspend or remove health practitioner's registration.

The national My Health Record is a digital health platform maintained by the Australian Digital Health Agency. The platform stores and allows access to medical records by registered health practitioners such as doctors and nurses.

State and territory agencies

Each state and territory is responsible for their own public hospitals, as well as the state or territory's health department (such as Queensland Health). For some internal territories (such as the Jervis Bay Territory) and all external territories (such as Norfolk Island), health services are provided by another state or territory government. Under the NHRA, public health care services are provided by local health districts (such as Metro North Hospital and Health Service in Queensland).

Ambulance services

Queensland and Tasmanian state governments cover the cost of ambulance services for their citizens, both in the state and while interstate. Outside of Queensland and Tasmania, the cost of ambulance services varies state-by-state, but is either a call out fee plus a per-kilometre charge, or a membership to that state's ambulance provider.[43] Each state and territory has their own ambulance service, such as NSW Ambulance, Ambulance Victoria or the Queensland Ambulance Service.

Non-government organisations

Australian Red Cross Lifeblood collects blood, plasma and other essential tissue and organ donations and provides them to healthcare providers. The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) funds competitive health and medical research, and develops statements on policy issues.[42] The Royal Flying Doctor Service provides both emergency and primary health care in rural and regional Australia using aircraft.[44] Heart of Australia provides specialist cardiac and respiratory investigation and treatment services in rural and regional Queensland, particularly mining towns, using specially-equipped large trucks.[45]

Challenges

Workforce

In a report published by HealthWorkforce Australia in March 2012, a shortage of nearly 3,000 doctors, over 100,000 nurses and more than 80,000 registered nurses was predicted in the year 2025. In the conclusion of the report, the HWA explains: "For nurses, given the size of the projected workforce shortages presented in this report, HWA will conduct an economic analysis to quantify the cost to allow an assessment of the relative affordability of the modelled scenarios to close the projected gap." Governments, Higher Education and Training, Professions and Employers are also identified as key players in the process of addressing future challenges.[46] The mental health of health professionals in Australia is a growing concern, so much so that an organisation called Crazysocks4docs Trust Foundation was established by Melbourne cardiologist Geoff Toogood.[47][48] The organisation aims to break down the stigma of health professionals experiencing mental health issues through such initiatives as its annual flagship event, Crazy Socks 4 Docs Day.[49][50] However, some of those within the medical field have been both complimentary and critical of the crazy socks initiative.[51][52]

Quality of care

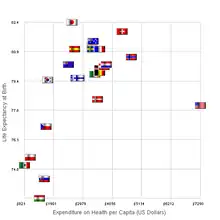

An international comparative study, 'Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: An International Update on the Comparative Performance of American Health Care' was published by The Commonwealth Fund in May 2007 and compared the health care systems in six countries (Australia, Canada, Germany, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States). It found that in the healthy lives category, "Australia ranks highest, scoring first or second on all three indicators", although its overall ranking in the study was below the UK and Germany systems, tied with New Zealand's and above those of Canada and far above the U.S.[53][54] A new study published in July 2017 as part of the same 'Mirror, Mirror' series by The Commonwealth Fund compared the health care systems in 11 countries (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States) and found that Australia was now one of the top ranked countries overall, alongside the United Kingdom and the Netherlands.[55]

A global study of end of life care, conducted by the Economist Intelligence Unit, part of the group which publishes The Economist magazine, published the compared end of life care, gave the highest ratings to Australia and the UK out of the 40 countries studied, the two country's systems receiving a rating of 7.9 out of 10 in an analysis of access to services, quality of care and public awareness.[56]

Aging population

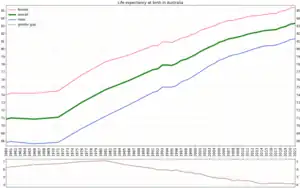

Australia's life expectancy is approximately 83 years, however 10 of these years are expected to include an increase in disability from a chronic disease. The increase in chronic diseases are a contributor of higher healthcare costs overall.[57] Additionally the older generation shows an increased need for health services, and utilizes services frequently. From the years 1973 to 2013 the total number of people 65 or older tripled, increasing from 1.1 million to 3.3. As for the population of 85 and older there was an increase from 73,100 to 439,600. In order for the Australian health care system to handle the gradual population aging, government and administration must develop new policies and programs to accommodate the needs of changing demographics.[9]

Rural and remote health care

Health care services, their availability and the health outcomes of those who live in rural and remote parts of Australia can differ greatly from metropolitan areas. In recent reports, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare noted that "compared with those in Major Cities, people in regional and remote areas were less likely to report very good or excellent health", with life expectancy decreasing with increasing remoteness: "[c]ompared with Major Cities, the life expectancy in regional areas is 1–2 years lower and in remote areas is up to 7 years lower." It was also noted that Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander peoples experienced worse health than non-Indigenous Australians.

Affordability

Government subsidies have not kept up with increasing fees charged by medical professionals or the increasing cost of medicines.[17] Data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare shows that out-of-pocket payments increased four-and-a-half times faster than government funding in 2014–15.[58] This has led to large numbers of patients skipping treatment or medicine.[59] Australian out-of-pocket health expenses are the third highest in the developed world.[58]

Adoption of US-style preferred provider contracts

Since around 2010 Private Health Insurance (PHI) companies have introduced Preferred Provider contracts with healthcare providers. Whilst seemingly a win win scenario at the start the PHI companies now have a great deal of control over these providers. The introduction of 1- Differential rebating 2- HICAPS and access to members data 3- Patient steering have led to a high level of discontent amongst healthcare providers. The Senate enquiry into the value and affordability of private health insurance conducted 2017–18 led to a host of recommendations to Parliament to end these practices however as of the time of writing the Minister for Health has not taken any action. The ACCC have also looked at this matter without recommending any action be taken. The impact of these PHI policies has been overwhelmingly to place financial pressure on healthcare providers and reduce the choice of healthcare provider to the patient as rebate amounts differ depending on which provider the patient attends. This has led to a number of bankruptcies in the Dental field.

Corporatisation of the dental industry

The Australian Dental Association (ADA) set quality and care standards for the industry, but provide no standardised pricing schedule for services and treatment. Large corporate dental practices, which have a wide footprint, often have check-up and service KPIs. As there is no standard pricing schedule, this can quite often leave patients with large expenses, and on occasion unnecessary treatment. It also leads to cases where identical treatment plans can have drastically different pricing.[60]

Other health care programs

- National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) – Australia's national disability-related health care program, managed by the National Disability Insurance Agency

- Healthdirect Australia – Healthdirect provides access to quality health information and is funded by the Australian Government.[61]

- DoctorConnect – To encourage overseas doctors to work in Australia.[62]

Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme

The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) subsidises certain prescribed pharmaceuticals. The PBS pre-dates Medicare, being established in 1948. It is generally considered a separate health policy to 'Medicare'. The PBS is now administered by the Department of Human Services Insurance, with input from a range of other bodies such as the Pharmaceutical Benefits Pricing Authority.[63]

State/territory programs

State and Territory Governments also sometimes administer peripheral health programmes, such as free dentistry for school students and community sexual health programmes.

Dental care services

With some exceptions, such as the Teen Dental Plan, dental care is generally not covered by Medicare for all Australians, although the various States and Territories provide free or subsidised dental services to certain categories of the population, such as Health Care Card and Pensioner Concession Card holders.[64]: 19 For example, Victoria provides subsidized dental care to concession card holders through a network of community clinics[65] and the Royal Dental Hospital.[66] There is also a voucher system available for general and emergency dental care where these can not be met by the public system. Vouchers allow patients to receive $799 worth of necessary general and/or emergency dental treatment at a time. The patient co-payment in these situations is generally $27 a visit up to a maximum of 4 visits at $108.[67]

National Diabetes Services Scheme

The National Diabetes Services Scheme is funded by the Australian government to deliver diabetes-related products at affordable prices.

Sick leave

Sick leave has its origins in trade union campaigns for its inclusion in industrial agreements. In Australia, it was introduced into industrial awards in 1922.[68]

Under the Federal Government's industrial relations legislation, known as Fair Work,[69] eligible employees are entitled to 10 days of paid personal leave (sick/carer's leave) per year, which also carries over to subsequent years if not used.

In addition, Australian workers may be entitled to two days of compassionate leave for each permissible occasion where a member of their family or household contracts or develops a personal illness or sustains a personal injury that poses a threat to his or her life, or dies.

See also

- Aged care in Australia

- Australian paradox

- Biosecurity in Australia

- Dental care in adolescent Australians

- Emergency medical services in Australia

- Euthanasia in Australia

- Home medicines review

- Medical education in Australia

- Nursing in Australia

- Paramedics in Australia

- Private Health Insurance Ombudsman

- Rural health care in Australia

- International

References

- General Government Expenses, Budget 2007–08.

- Metherell, Mark (29 July 2009). "High Cost of Health Reform". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- Britnell, Mark (2015). In Search of the Perfect Health System. London: Palgrave. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-137-49661-4.

- "Health expenditure Australia 2017–18, Data visualisation". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

- Behan, Pamela (2007). Solving the Health Care Problem: How Other Nations Have Succeeded and Why the United States Has Not. SUNY Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0791468388. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- admin (17 April 2023). "The National Disability Insurance Scheme 2023 - A Quick Guide". Finder Hub. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- "Britannica World Data, Australia". 2009 Book of the Year. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2009. pp. 516–517. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- "Doctors and Nurses". 4102.0 – Australian Social Trends, April 2013. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 24 July 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- Johnson; Stoskopf, Carleen; Shi, Leiyu (2 March 2017). Comparative health systems : a global perspective. Johnson, James A., 1954–, Stoskopf, Carleen H. (Carleen Harriet), 1953–, Shi, Leiyu (2nd ed.). Burlington, MA. ISBN 9781284111736. OCLC 960840881.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Office of health Economics. "International Comparison of Medicines Usage: Quantitative Analysis" (PDF). Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- "Reports & data". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

- "Health Funding Facts". Department of Health and Aged Care. 11 April 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- "Enrolling in Medicare". Services Australia. 26 May 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- "Reciprocal Health Care Agreements". Services Australia. 20 December 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- "Medicare and private health insurance". Australian Tax Office. 1 July 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- "Health care and Medicare". Services Australia. 7 July 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- "Medical costs forcing Australians to skip healthcare". 4 August 2016.

- Thresholds and Concession Calculated Amounts Archived 29 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Medicare Australia.

- "Other Medicare support". Services Australia. 7 July 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- "Medicare Services for Indigenous Australians". Services Australia. 3 March 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- "Medicare services for rural and remote Australians". Services Australia. 3 March 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- "MBS programs and initiatives for allied health professionals – Australian Government Department of Human Services". www.humanservices.gov.au. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- "Funding types". National Health Funding Body. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- "Pay". National Health Funding Body. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- "Medicine and Medicare". Services Australia. 3 March 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- "Members Health".

- Private Health Insurance Administration Council, Annual Report 2009-10 (PDF), Private Health Insurance Administration Council, archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2012, retrieved 18 March 2012

- Private Health Insurance Ombudsman (PHIO)

- "PHIO's Annual Reports". Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- "Private Health Insurance in Australia". Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- "Private health insurance rebate". Australian Taxation Office. 31 August 2016. Archived from the original on 22 April 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- "Medicare Levy Surcharge". Private Health Insurance Ombudsman. Archived from the original on 22 August 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ATO: Medicare levy surcharge Archived 27 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- "Medicare Levy Surcharge". www.ato.gov.au. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- PrivateHealth.gov.au Australian Government Private Health Insurance Rebate

- ATO, Health insurance

- "HCF records strong revenue and membership growth in 2008–09, reaffirms commitment to not-for-profit model". The Hospitals Contribution Fund of Australia. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010.

- Britnell, Mark (2015). In Search of the Perfect Health System. London: Palgrave. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-137-49661-4.

- Health, Australian Government Department of. "Outcome 9: Private Health".

- "Basic Tier Cover: Health Insurance Reforms". Canstar. 12 March 2019.

- The NewDaily, 30 October 2019, Fool’s silver: Private health customers being overcharged for inferior cover

- Louise Fleming, Mary; Elizabeth Anne Parker (2011). Introduction to Public Health. Elsevier Australia. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0729540919. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- "Ambulance costs around Australia: why is it free in some states and not others? – ABC News". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 19 July 2018.

- "RFDS Your Health – Health Services". flyingdoctor.org.au. Archived from the original on 6 February 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- Wheeler, Joseph (2017). "Dr Rolf Gomes – The Heart Of Australia Truck – Bringing health equity to the bush". TEDxBrisbane. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- "Health Workforce 2025 Doctors, Nurses and Midwives – Volume 1" (PDF). HealthWorkforce Australia. Health Workforce 2025 – Doctors, Nurses and Midwives. March 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- "Who We Are". Crazy Socks 4 Docs. Crazysocks4docs Trust Foundation. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- "Meet The Founder". Crazy Socks 4 Docs. Crazysocks4docs Trust Foundation. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- Williams, Guy (4 June 2021). "Doctors normalise mental health issues among colleagues with annual Crazy Socks 4 Docs Day". ABC News. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- Durling, Lachlan (7 June 2021). "Crazy socks encourage GV Health docs to check in with one another". Shepparton News. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- Janakiramanan, Neela (6 June 2019). "Why Crazy Socks? Because every year over a million patients lose their doctors". Women's Agenda. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- Wen, Sophie (3 June 2020). "Socks don't fix the systemic stressors for burnt-out doctors". Women's Agenda. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- "Figure 2. Six Nation Summary Scores on Health System Performance" (PDF). commonwealthfund.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- Davis, Karen; Cathy Schoen; et al. (May 2007). "MIRROR, MIRROR ON THE WALL: AN INTERNATIONAL UPDATE ON THE COMPARATIVE PERFORMANCE OF AMERICAN HEALTH CARE" (PDF). The Commonwealth Fund.

- Schneider, Eric C; Sarnak, Dana O; Squires, David; Shah, Arnav; Doty, Michelle M (July 2017). Mirror, Mirror 2017: International Comparison Reflects Flaws and Opportunities for Better U.S. Health Care (PDF) (Report). The Commonwealth Fund. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- "UK comes top on end of life care – report". BBC News. 14 July 2010.

- Armstrong, Bruce K. (5 November 2007). "Challenges in health and health care for Australia" (PDF). Medical Journal of Australia. 187 (9): 485–489. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01383.x. PMID 17979607. S2CID 38979644.

- "Can you afford your healthcare? – YourLifeChoices". March 2017.

- "CSIRO PUBLISHING | Australian Journal of Primary Health".

- "How much does the dentist cost?". 9 February 2021.

- Australia, Healthdirect (17 March 2022). "Trusted Health Advice". www.healthdirect.gov.au.

- Health, Australian Government Department of (24 April 2019). "DoctorConnect". Australian Government Department of Health.

- Health, Australian Government Department of. "Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) | About the PBS". www.pbs.gov.au. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- "Report of the National Advisory Council on Dental Health" (PDF). health.gov.au. 23 February 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 February 2014.

- "General dental care – Dental Health Services Victoria". August 2019.

- "The Royal Dental Hospital of Melbourne – Dental Health Services Victoria". 17 September 2019.

- "Vouchers – Dental Health Services Victoria". 29 July 2013.

- "Sick Leave". Australian Council of Trade Unions. Archived from the original on 22 September 2006.

- "Sick & carer's leave". Fair Work Ombudsman. Retrieved 18 May 2021.