Ataluren

Ataluren, sold under the brand name Translarna, is a medication for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. It was designed by PTC Therapeutics.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Translarna |

| Other names | PTC124 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| License data | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.132.097 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H9FN2O3 |

| Molar mass | 284.246 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Medical use

Ataluren is used in the European Union to treat people with Duchenne muscular dystrophy who have a nonsense mutation in the dystrophin gene, can walk, and are more than five years old.[1]

Contraindications

People who are pregnant or breast feeding should not take ataluren.[1]

Adverse effects

More than 10% of people taking ataluren in clinical trials experienced vomiting; more than 5% experienced diarrhea, nausea, headache, upper abdominal pain, and flatulence; between 1% and 5% of people experienced decreased appetite and weight loss, high levels of triglycerides, high blood pressure, cough, nosebleeds, abdominal discomfort, constipation, rashes, pain in their arms, legs, and chest muscles, blood in their urine, urinary incontinence, and fever.[1]

Interactions

Aminoglycosides should not be given to someone taking ataluren, as they interfere with its mechanism of action. Caution should be used with drugs that induce UGT1A9, or that are substrates of OAT1, OAT3, or OATP1B3.[1]

Pharmacology

While a large number of studies failed to identify the biological target of ataluren,[3][4][5][6][7][8] it was discovered to bind and stabilize firefly luciferase, thus explaining the mechanism by which it created a false positive effect on the read through assay.[9][10]

Ataluren is thought to make ribosomes less sensitive to premature stop codons (an effect referred to as "read-through") by promoting insertion of certain near-cognate tRNA at the site of nonsense codons with no apparent effects on downstream transcription, mRNA processing, stability of the mRNA or the resultant protein, thereby making a functional protein similar to the non-mutated endogenous product.[11] It seems to work particularly well for the stop codon 'UGA'.[4][12]

Studies have demonstrated that ataluren treatment increases expression of full-length dystrophin protein in human and mouse primary muscle cells containing the premature stop codon mutation for Duchenne muscular dystrophy and rescues striated muscle function.[12] Studies in mice with the premature stop codon mutation for cystic fibrosis demonstrated increased CFTR protein production and function.[13] Extending on this work, a mechanistic study with yeast and human cells has elucidated the details of ataluren-mediated nonstandard codon-anticodon base pairings which result in specific amino acid substitutions at specific codon positions in the CFTR protein.[11]

The European Medicines Agency review on the approval of ataluren concluded that "the non-clinical data available were considered sufficient to support the proposed mechanism of action and to alleviate earlier concerns on the selectivity of ataluren for premature stop codons."[14]

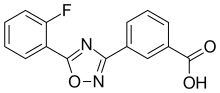

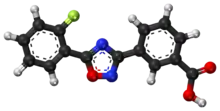

Chemistry

Ataluren is an oxadiazole; its chemical name is 3-[5-(2-Fluorophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-3-yl]benzoic acid.[4]

History

Ataluren was discovered by scientists at PTC Therapeutics in a collaboration with Lee Sweeney's lab at the University of Pennsylvania, which was initially funded in part by Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy.[15] The team used phenotypic screening of a chemical library to identify compounds that increased the amount of protein expressed by mutated genes, and then optimized one of the hits in the screen to create this drug.[7][5][12] As with the results of many cell-based screens, the biological target of ataluren is not known.[4]

Phase I clinical trials started in 2004.[16]

In 2010, PTC Therapeutics released preliminary results of its phase IIb clinical trial for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, with participants not showing a significant improvement in the six minute walk distance after the 48 weeks of the trial.[17]

In May 2014, ataluren received a positive opinion from the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA)[18] and received market authorization from the European Commission to treat people with nonsense mutation Duchenne muscular dystrophy in August 2014;[2] a confirmatory phase III clinical trial was required.[19] By December it was on the market in Germany, France, Italy, Denmark, Spain and a number of other European Union countries.[19]

In February 2016, FDA declined to accept PTC Therapeutics new drug application for ataluren, which was based on a clinical trial in which ataluren missed its primary endpoint; PTC appealed and the FDA declined again in October 2016.[20]

In July 2016, NHS England agreed a Managed Access Agreement (MAA) for Translarna providing reimbursed patient access to Translarna in England via a five-year MAA. This followed a positive recommendation from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in April 2016, subject to PTC and NHS England finalizing the terms of the MAA. NICE issued its final guidance later in July with implementation of the MAA for patients following within two months.[21]

In March 2017, PTC terminated development of ataluren for cystic fibrosis due to lack of efficacy in the phase III trials.[22][23][24]

References

- "Translarna - Summary of Product Characteristics". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. 24 April 2017. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Translarna EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- Karijolich J, Yu YT (August 2014). "Therapeutic suppression of premature termination codons: mechanisms and clinical considerations (review)". International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 34 (2): 355–362. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2014.1809. PMC 4094583. PMID 24939317.

- Pace A, Buscemi S, Piccionello AP, Pibiri I (2015). Scriven EF, Ramsden CA (eds.). 3. Recent Advances in the Chemistry of 1,2,4-Oxadiazoles. Advances in Heterocyclic Chemistry. Academic Press. p. 127. ISBN 9780128028742.

- Roberts RG (25 June 2013). "A read-through drug put through its paces". PLOS Biology. 11 (6): e1001458. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001458. PMC 3692443. PMID 23824301.

- Devitt L (25 June 2013). "Researchers question 'read-through' mechanism of muscular dystrophy drug ataluren : Spoonful of Medicine". Nature Medicine: Spoonful of Medicine. Archived from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Press Release: Questions Raised About Process Used to Identify Experimental Drug for Genetic Disease". NIH via Drug Discovery & Development. 3 February 2009. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- Schmitz A, Famulok M (May 2007). "Chemical biology: ignore the nonsense". Nature. 447 (7140): 42–43. Bibcode:2007Natur.447...42S. doi:10.1038/nature05715. PMID 17450128. S2CID 29789135.

- Auld DS, Thorne N, Maguire WF, Inglese J (March 2009). "Mechanism of PTC124 activity in cell-based luciferase assays of nonsense codon suppression". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (9): 3585–3590. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.3585A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0813345106. PMC 2638738. PMID 19208811.

- Auld DS, Lovell S, Thorne N, Lea WA, Maloney DJ, Shen M, et al. (March 2010). "Molecular basis for the high-affinity binding and stabilization of firefly luciferase by PTC124" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (11): 4878–4883. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.4878A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0909141107. PMC 2841876. PMID 20194791. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 August 2023. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Roy B, Friesen WJ, Tomizawa Y, Leszyk JD, Zhuo J, Johnson B, et al. (November 2016). "Ataluren stimulates ribosomal selection of near-cognate tRNAs to promote nonsense suppression". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (44): 12508–12513. Bibcode:2016PNAS..11312508R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1605336113. PMC 5098639. PMID 27702906.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Welch EM, Barton ER, Zhuo J, Tomizawa Y, Friesen WJ, Trifillis P, et al. (May 2007). "PTC124 targets genetic disorders caused by nonsense mutations". Nature. 447 (7140): 87–91. Bibcode:2007Natur.447...87W. doi:10.1038/nature05756. PMID 17450125. S2CID 4423529.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Du M, Liu X, Welch EM, Hirawat S, Peltz SW, Bedwell DM (February 2008). "PTC124 is an orally bioavailable compound that promotes suppression of the human CFTR-G542X nonsense allele in a CF mouse model". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (6): 2064–2069. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.2064D. doi:10.1073/pnas.0711795105. PMC 2538881. PMID 18272502.

- Haas M, Vlcek V, Balabanov P, Salmonson T, Bakchine S, Markey G, et al. (January 2015). "European Medicines Agency review of ataluren for the treatment of ambulant patients aged 5 years and older with Duchenne muscular dystrophy resulting from a nonsense mutation in the dystrophin gene". Neuromuscular Disorders. 25 (1): 5–13. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2014.11.011. PMID 25497400. S2CID 41468577.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - "Press release: PTC Therapeutics Announces $15.4 Million NIH Research Grant for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy | Evaluate". PTC, University of Pennsylvania, and the NIH via Evaluate Group. 10 July 2007. Archived from the original on 23 August 2023. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "PTC Therapeutics, Inc. Initiates Phase 2 Study Of PTC124 In Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy". BioSpace (Press release). 27 January 2006. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- "PTC Therapeutics, Inc. and Genzyme Corporation Announce Preliminary Results from the Phase 2b Clinical Trial of Ataluren; Primary Endpoint Does Not Reach Statistical Significance within Duration of Study". BioSpace (Press release). 3 March 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- "PTC Therapeutics Receives Positive Opinion from CHMP for Translarna (ataluren)". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "PTC Therapeutics Announces Launch of Translarna (ataluren) in Germany". MarketWatch. 3 December 2014. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- Pagliarulo N (17 October 2016). "FDA snubs PTC appeal for Duchenne drug". BioPharma Dive. Archived from the original on 28 January 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "NHS England successfully negotiates access to new drug treatment for children with duchenne muscular dystrophy". NHS England.

- "Drug Company Ends Ataluren Program for CF Nonsense Mutations". Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. 3 March 2017.

- DeFrancesco L (May 2017). "Drug pipeline: 1Q17". Nature Biotechnology. 35 (5): 400. doi:10.1038/nbt.3874. PMID 28486449. S2CID 205284732.

- Aslam AA, Sinha IP, Southern KW (March 2023). "Ataluren and similar compounds (specific therapies for premature termination codon class I mutations) for cystic fibrosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (3): CD012040. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012040.pub3. PMC 9983356. PMID 36866921.