Armenians in Azerbaijan

Armenians in Azerbaijan (Armenian: Հայերն Ադրբեջանում, romanized: Hayern Adrbejanum; Azerbaijani: Azərbaycan erməniləri) are the Armenians who lived in great numbers in the modern state of Azerbaijan and its precursor, Soviet Azerbaijan. According to the statistics, about 500,000 Armenians lived in Soviet Azerbaijan prior to the outbreak of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War in 1988.[1][2] Most of the Armenian-Azerbaijanis however had to flee the republic, like Azerbaijanis in Armenia, in the events leading up to the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, a result of the ongoing Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict. Atrocities directed against the Armenian population took place in Sumgait (February 1988), Ganja (Kirovabad, November 1988) and Baku (January 1990). Today the vast majority of Armenians in Azerbaijan live in territory controlled by the break-away region Nagorno-Karabakh[3][4] which declared its unilateral act of independence in 1991 under the name Nagorno-Karabakh Republic but has not been recognised by any country, including Armenia.

Հայերն Ադրբեջանում Azərbaycan erməniləri | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| 217 (2009) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Baku | |

| Languages | |

| Armenian, Azerbaijani | |

| Religion | |

| Armenian Apostolic Church | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Armenians in Nakhchivan, Armenians in Baku, Armenians in Russia, Armenians in Turkey |

| Part of a series on |

| Armenians |

|---|

|

| Armenian culture |

| By country or region |

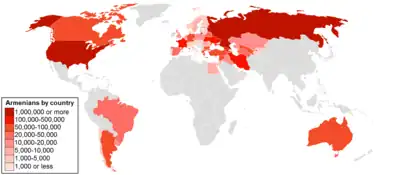

Armenian diaspora Russia |

| Subgroups |

| Religion |

| Languages and dialects |

| Persecution |

Non-official sources estimate that the number Armenians living on Azerbaijani territory outside Nagorno-Karabakh is around 2,000 to 3,000, and almost exclusively comprises persons married to Azerbaijanis or of mixed Armenian-Azerbaijani descent.[5] The number of Armenians who are likely not married to Azerbaijanis and are not of mixed Armenian-Azerbaijani descent are estimated at 645 (36 men and 609 women) and more than half (378 or 59 per cent of Armenians in Azerbaijan outside Nagorno-Karabakh) live in Baku and the rest in rural areas. They are likely to be the elderly and sick, and probably have no other family members.[5][6][7] Armenians in Azerbaijan are at a great risk as long as the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict remains unsettled.[8][9][10][11][12] In Azerbaijan, the status of Armenians is precarious.[13] Armenian churches remain closed, because of the large emigration of Armenians and fear of Azerbaijani attacks.[14]

History

Armenians in Baku

Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh

Armenians have lived in the Karabakh region since the period of antiquity.[15][16] In the beginning of the 2nd century BC. Karabakh became a part of Armenian Kingdom as province of Artsakh. In the 14th century, a local Armenian leadership emerged, consisting of five noble dynasties led by princes, who held the titles of meliks and were referred to as Khamsa (five in Arabic). The Armenian meliks maintained control over the region until the 18th century. In the early 16th century, control of the region passed to the Safavid dynasty, which created the Ganja-Karabakh province (beylerbeydom, bəylərbəylik). Despite these conquests, the population of Upper Karabakh remained largely Armenian.[17]

Karabakh passed to Imperial Russia by the Kurekchay Treaty, signed between the Khan of Karabakh and Tsar Alexander I of Russia in 1805, and later further formalized by the Russo-Persian Treaty of Gulistan in 1813, before the rest of Transcaucasia was incorporated into the Empire in 1828 by the Treaty of Turkmenchay. In 1822, the Karabakh khanate was dissolved, and the area became part of the Elizavetpol Governorate within the Russian Empire.

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, Karabakh became part of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic, but this soon dissolved into separate Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Georgian states. Over the next two years (1918–1920), there were a series of short wars between Armenia and Azerbaijan over several regions, including Karabakh. In July 1918, the First Armenian Assembly of Nagorno-Karabakh declared the region self-governing and created a National Council and government.[18] In September 1918, Azerbaijani–Ottoman forces captured the city of Shusha, the capital of the Karabakh Council, however, were unable to penetrate the countryside due to the efforts of local Armenians.[19] Following the Armistice of Mudros on 30 October 1918, Ottoman forces were obligated to withdraw from the South Caucasus, including Shusha, after which their garrison was supplemented by the British. On 15 January 1919, the British governor of Baku, General Thomson appointed Khosrov bey Sultanov the "Governor-General of Karabakh and Zangezur" within Azerbaijan, despite neither region being completely under Azerbaijani control. On 5 June 1919, due to the refusal of the Karabakh assembly to submit to Azerbaijani authority as prescribed by British command, 2,000 mounted Kurdish irregulars led by the Sultan bey Sultanov—the brother of Khosrov—looted several Armenian villages in the outskirts of Shushi including Khaibalikend, Krkejan, Pahliul, Jamillu, and several remote hamlets resulting in the deaths of some 600 Armenians. As a result of the bloodshed, the Karabakh Council was compelled to sign a provisional accord with the Azerbaijani government on 22 August 1919, submitted to their rule pending their final status decided in the Paris Peace Conference.[20]

As the Paris Peace Conference was inconclusive on the issue of the South Caucasus territorial disputes, on 19 February 1920 Khosrov bey Sultanov issued an ultimatum to the Karabakh Council to consent to the region's permanent incorporation into Azerbaijan. During meetings of the Eighth Assembly of Armenians of Karabakh from 28 February to 4 March, the delegates expressed discontent with the Azerbaijani administration and warned that they would resort to countermeasures if their existence was threatened.[21] In the uprising that followed, due to the unsuccessful attempt by local Armenian forces to disarm the Azerbaijani garrisons in Shusha and Khankend, the former befell a pogrom which saw the Armenian half of the town looted and destroyed, with its Armenian inhabitants evicted and 500–20,000 massacred.[22][23][24][25][26]

In April 1920, while the Azerbaijani army was locked in Karabakh fighting local Armenian forces, Azerbaijan was taken over by Bolsheviks.[17] Subsequently, the disputed areas of Nagorno-Karabakh, Zangezur, and Nakhchivan came under the control of Armenia. During July and August 1920, however, the Red Army occupied mountainous Karabakh, Zangezur, and part of Nakhchivan. Later on, for basically political reasons, the Soviet Union agreed to a division under which Zangezur would fall under the control of Armenia, while Karabakh and Nakhchivan would be under the control of Azerbaijan. In addition, the mountainous part of Karabakh that had come to be named Nagorno-Karabakh was granted an autonomous status as the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, giving Armenians more rights than were given to Azerbaijanis in Armenia[27] and enabling Armenians to be appointed to key positions and attend schools in their first language.

With the Soviet Union firmly in control of the region, the conflict over the region died down for several decades. The Armenians in Karabakh were not repressed to a substantial extent.[27] Local schools offered education in Armenian but taught Azerbaijani history and not the history of the Armenian people; the population had access to Armenian-language television broadcast by a Stepanakert-based channel controlled from Baku, and later directly from Armenia as well, though in an unfavourable manner.[28] Unlike in Baku, cases of mixed Armenian-Azerbaijani marriages in Nagorno-Karabakh were very rare.[29] The autonomy of Nagorno-Karabakh led to the rise of Armenian nationalism and the Armenians' determination in claiming independence. With the beginning of the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the question of Nagorno-Karabakh re-emerged.

Armenians in Ganja

The 69,000 Armenians of the Elizavetpol uezd (modern-day Dashkasan, Gadabay, Goranboy, and Shamkir districts) had in 1918 recognised Azerbaijani authority due to their geographically isolated position as a result of which Armenia was unable to incorporate them. As they had cooperated with Nuri Pasha's ultimatum to disarm and submit, the Armenians of Elizavetpol were not massacred, however, they experienced difficulties in tending to their fields (100 of whom were killed whilst doing so) and traversing roads where they were attacked by "disgruntled refugees" and "lawless bands" who were also raiding the properties of local khans and beys ("chiefs"; "lords").[30] On 9 April 1920, at the height of the Armenian–Azerbaijani war and the clashes in the Kazakh uezd, Azerbaijani soldiers burned the Armenian villages of Badakend (Balakend) and Chardakhly (Çardaqlı) in the district.[31]

According to Human Rights Watch, In 1991 Azerbaijani OMON and Soviet military forces jointly started "a campaign of violence to disperse Armenian villagers from areas north and south of Nagorno-Karabakh, a territorial enclave in Azerbaijan where Armenian communities have lived for centuries".[32]

"However, the unstated goal was to "convince" the villagers half are pensioners to relocate permanently in Armenia."[32] This military action was officially called "Operation Ring", because its basic strategy consists of surrounding villages (included Martunashen and Chaykand) with tanks and armored personnel carriers and shelling them. Azerbaijani villagers were allowed to come and loot the empty Armenian villages—by the end of the operation, more than ten thousand Armenian villagers were forced to leave Azerbaijan.[32]

The majority Armenian population started a movement that culminated in the unilateral declaration of independence.

Armenians in Nakhchivan

.jpg.webp)

Armenians had a historic presence in Nakhchivan (In Armenian Նախիջևան, Nakhijevan). According to an Armenian tradition, Nakhchivan was founded by Noah, of the Abrahamic religions. It became part of the Satrapy of Armenia under Achaemenid Persia c. 521 BC. In 189 BC, Nakhchivan was part of the new Kingdom of Armenia established by Artaxias I.[15] In 428, the Armenian Arshakuni monarchy was abolished and Nakhchivan was annexed by Sassanid Persia. In 623 AD, possession of the region passed to the Byzantine Empire. Nakhchivan itself became part of the autonomous Principality of Armenia under Arab control. After the fall of the Arab rule in the 9th century, the area became the domain of several Muslim emirates of Arran and Azerbaijan. Nakhchivan became part of the Seljuk Empire in the 11th century, followed by becoming the capital of the Atabegs of Azerbaijan in the 12th century. In the 1220s it was plundered by Khwarezmians and Mongols. In the 15th century, the weakening Mongol rule in Nakhchivan was forced out by the Turcoman dynasties of Kara Koyunlu and Ak Koyunlu.[15]

In the 16th century, control of Nakhchivan passed to the Safavid dynasty of Persia. In 1604, Shah Abbas I Safavi, concerned that the lands of Nakhchivan and the surrounding areas would pass into Ottoman hands, decided to institute a scorched earth policy. He forced the entire local population, Armenians, Jews and Muslims alike, to leave their homes and move to the Persian provinces south of the Aras River. Many of the deportees were settled in the neighborhood of Isfahan that was named New Julfa since most of the residents were from the original Julfa (a predominantly Armenian town).[15]

After the last Russo-Persian War and the Treaty of Turkmenchay, the Nakhchivan khanate passed into Russian possession in 1828. The Nakhchivan khanate was dissolved, and its territory was merged with the territory of the Erivan khanate and the area became the Nakhichevan uezd of the new Armenian Oblast, which was reformed into the Erivan Governorate in 1849. A resettlement policy implemented by the Russian authorities encouraged massive Armenian immigration to Nakhchivan from various parts of the Ottoman Empire and Persia. According to official statistics of the Russian Empire, by the turn of the 20th century Azerbaijanis made up 57% of the uezd's population, while Armenians constituted 42%.

During the Russian Revolution of 1905, conflict erupted between the Armenians and the Azerbaijanis, culminating in the Armenian-Tatar massacres. In the final year of World War I, Nakhchivan was the scene of more bloodshed between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, who both laid claim to the area. By 1914, the Armenian population was at 40% while the Azerbaijani population increased to roughly 60%. After the February Revolution, the region was under the authority of the Special Transcaucasian Committee of the Russian Provisional Government and subsequently of the short-lived Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic. When the TDFR was dissolved in May 1918, Nakhchivan, Nagorno-Karabakh, Zangezur (today the Armenian province of Syunik and part of Vayots Dzor), and Qazakh were heavily contested between the newly formed and short-lived states of the Democratic Republic of Armenia (DRA) and the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR). In June 1918, the region came under Ottoman occupation. Under the terms of the Armistice of Mudros, the Ottomans agreed to pull their troops out of the Transcaucasus to make way for the forthcoming British military presence.[33]

After a brief British occupation and the fragile peace they tried to impose, in December 1918, with the support of Azerbaijan's Musavat Party, Jafargulu Khan Nakhchivanski declared the Republic of Aras in the Nakhichevan uezd of the former Yerevan Governorate assigned to Armenia by Wardrop. The Armenian government did not recognize the new state and sent its troops into the region to take control of it. The conflict soon erupted into the violent Aras War. By mid-June 1919, however, Armenia succeeded in establishing control over Nakhchivan and the whole territory of the self-proclaimed republic. The fall of the Aras republic triggered an invasion by the regular Azerbaijani army and by the end of July, Armenian troops were forced to leave Nakhchivan City to the Azerbaijanis. In mid-March 1920, Armenian forces launched an offensive on all of the disputed territories, and by the end of the month both the Nakhchivan and Zangezur regions came under stable but temporary Armenian control. In July 1920, the 11th Soviet Red Army invaded and occupied the region and on July 28, declared the Nakhchivan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic with "close ties" to the Azerbaijan SSR. A referendum was called for the people of Nakhchivan to be consulted. According to the formal figures of this referendum, held at the beginning of 1921, 90% of Nakhchivan's population wanted to be included in the Azerbaijan SSR "with the rights of an autonomous republic." The decision to make Nakhchivan a part of modern-day Azerbaijan was cemented March 16, 1921, in the Treaty of Moscow between Bolshevist Russia and Turkey. The agreement between the Soviet Russia and Turkey also called for attachment of the former Sharur-Daralayaz uezd (which had a solid Azerbaijani majority) to Nakhchivan, thus allowing Turkey to share a border with the Azerbaijan SSR. This deal was reaffirmed on 23 October 1921 by the Treaty of Kars.

In the years following the establishment of Soviet rule, Nakhchivan saw a significant demographic shift. Its Armenian population gradually decreased as many emigrated. According to statistics published by the Imperial Russian government in 1916, Armenians made up 40% of the population of the Nakhchivan uezd.[34] The borders of the uezd were redrawn and in the 1926 all-Soviet census 11% of region's population was Armenian,.[35] By 1979 this number had shrunk to 1.4%. The Azerbaijani population, meanwhile increased substantially with both a higher birth rate and immigration (growing from 85% in 1926 to 96% by 1979). The Armenian population saw a great reduction in their numbers throughout the years repatriating to Armenia and elsewhere.

Some Armenian political groupings of the Republic of Armenia and the Armenian diaspora, among them most notably the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) claim that Nakhchivan should belong to Armenia. However, Nakhchivan is not officially claimed by the government of Armenia. But huge Armenian religious and cultural remnants are witness of the historic presence of Armenians in the Nakhchivan region. Recently the Medieval Armenian cemetery of Jugha (Julfa) in Nakhchivan, regarded by Armenians as the biggest and most precious repository of medieval headstones marked with Christian crosses – khachkars (of which more than 2,000 were still there in the late 1980s), has completely been destroyed by Azerbaijani soldiers in 2006.

Armenians in the Greater Caucasus slopes

A year prior to the Russian Revolution, there were 80 thousand Armenians,[36] whose ancestors migrated there in 15th–19th centuries, in the districts on the foothills of the Greater Caucasus Mountains (in the districts of Aresh, Geokchay, Nukha, Shemakha, and Zakatal),[36] the territory of all was inherited by Azerbaijan.[37] Most of the Armenian towns and villages in these districts were destroyed by the Azerbaijani–Ottoman advance against the Baku Commune in late 1918.[38] By 1919, 23 Armenian parochial schools in Shemakha had been closed, and slightly more than 10% of the district's pre-revolution Armenian population survived as evidenced by the 33 wagonloads of their bones. In the Aresh and Nukha districts of the Elizavetpol Governorate, only 3 of 51 Armenian and Udi villages remained, indicating the massacre of 25,000 and the kidnappings of thousands of Armenian girls and women by Azerbaijani and Turkish officers.[31] 48 Armenian villages were destroyed and the female population kidnapped and raped.[39] By 1919, only half of the two districts' Armenian population had survived, forced into the remaining three villages of Nidzh (Nij), Vardashen (Oğuz), and Jalut (Calut). The remaining villages were later destroyed in March 1920 in retaliation for the uprising in Nagorno-Karabakh—causing the survivors to flee up into the Greater Caucasus Mountains or to Georgia. Many of these Armenians were forced into labor by beys, and were often unable to reclaim their stolen possessions. One of the Armenian deputies in Azerbaijan's parliament denounced the treatment of the Armenians in the Greater Caucasus slopes, but their appeals were ignored by the government of Azerbaijan. 1,500 Armenians from this region were later resettle in the Etchmiadzin and Surmalu uezds ("counties") of Armenia.[31]

Conditions today

The Armenians still remaining in Azerbaijan practically live in virtual hiding, and have also changed their Armenian names and surnames to Azerbaijani names because they have to maintain an extremely low profile to avoid harassment and physical attacks. They have continued to complain (in private due to fear of attacks) that they remain subject to harassment and human rights violations and therefore have to hide their identity.[40] According to a 1993 United States Immigration and naturalization service report:[41]

It is clear that Armenians are the target of violence from societal forces and that the Azerbaijani government is unable or in some instances unwilling to control the violence or acts of discrimination and harassment. Some sectors of the government, such as the Department of Visas and Registrations mentioned above, appear unwilling to enforce the governments stated policy on minorities. As long as the Armenian-Azeri conflict over the fate of Karabakh continues, and possibly long after a settlement is reached, Armenian inhabitants of Azerbaijan will have no guarantees of physical safety.

A report by the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) released in May 2011 found that their conditions had barely improved. It found that:

...people of Armenian origin are at risk of being discriminated against in their daily lives. Certain people born of mixed Armenian-Azerbaijani marriages choose to use the name of their Azerbaijani parent so as to avoid problems in their contacts with officialdom; others who did not immediately apply for Azerbaijani identity documents when the former Soviet passports were done away with today encounter difficulties in obtaining identity papers.[42]

It further expressed concern over the "fact that the constant negative official and media discourse concerning the Republic of Armenia helps to sustain a negative climate of opinion regarding people of Armenian origin coming under the Azerbaijani authorities' jurisdiction."[42] It recommended that the government "work actively to improve the climate of opinion concerning Armenians coming under Azerbaijan’s jurisdiction."[42]

During the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War large parts of the Armenian-controlled Republic of Artsakh were captured by Azerbaijan.[43] While most of the Armenian residents fled in advance of the Azerbaijani army, with Armenian cities such as Hadrut being entirely depopulated, the few who remained behind were mistreated or even killed by Azerbaijani soldiers.[44] There have also been numerous reports that Armenian prisoners of war were tortured and nineteen were executed in captivity.[45][46] Armenian soldiers were also brutally mistreated, including multiple instances of beheadings recorded on video.[47]

Famous Armenians from Azerbaijan

- Hovhannes Bagramyan Army Commander, Marshal of the Soviet Union

- Hovannes Adamian, designer of color television

- Alexander Shirvanzade, playwright and novelist, awarded by the "People's Writer of Armenia" and "People's Writer of Azerbaijan" titles

- Boris Babaian, pioneering creator of supercomputers in the Soviet Union

- Armen Ohanian, an Armenian dancer, actress, writer and translator

- Alexey Ekimyan, composer and police general

- Garry Kasparov, chess grandmaster and former world chess champion

- Vladimir Akopian, chess player

- Ashot Nadanian, chess player

- Vladimir Bagirov, chess player

- Yevgeny Petrosyan, comedian

- Georgy Shakhnazarov, political scientist

- Rafael Kaprelyan, test pilot, Hero of the Soviet Union

- Avet Terterian, composer

- Sergey Petrosyan, weightlifter

- Karina Aznavourian, épée fencer

- Karapet Karapetyan, kickboxer

- Yura Movsisyan, football player

See also

Notes

- Memorandum from the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights to John D. Evans, Resource Information Center, 13 June 1993.

- "Implementation of the Helsinki Accords: Human Rights and Democratization in the Newly Independent States of the former Soviet Union" (Washington, DC: U.S. Congress, Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, January 1993), p. 118.

- Demographic indicators: Population by ethnic groups Archived December 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Assessment for Armenians in Azerbaijan, Minorities At Risk Project". Archived from the original on 2011-05-25. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- Этнический состав Азербайджана (по переписи 1999 года) Archived 2013-08-21 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- "Definitions of national identity, nationalism and ethnicity in post-Soviet Azerbaijan in the 1990s" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2010-12-15.

- "European Commission Against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI), Second Report on Azerbaijan, CRI(2007)22, May 24, 2007". Archived from the original on June 3, 2008. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- "University of Maryland Center for International Development and Conflict Management. Minorities at Risk: Assessment of Armenians in Azerbaijan, Online Report, 2004". Archived from the original on 2011-05-25. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- Razmik Panossian. The Armenians. Columbia University Press, 2006; p. 281

- Mario Apostolov. The Christian-Muslim Frontier. Routledge, 2004; p. 67

- Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. 2001

- Barbara Larkin. International Religious Freedom (2000): Report to Congress by the Department of State. DIANE Publishing, 2001; p. 256

- Azerbaijan: The status of Armenians, Russians, Jews and other minorities, report, 1993, INS Resource Information Center, p. 10

- United States Department of State, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 1992 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, February 1993), p. 708

- Hewsen, Robert H. Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2001.

- R. Schmitt, M. L. Chaumont. "Armenia and Iran". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 2012-01-21. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- Cornell, Svante E. The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict Archived 2013-04-18 at the Wayback Machine. Uppsala: Department of East European Studies, April 1999.

- The Nagorno-Karabagh Crisis: A Blueprint for Resolution Archived 2000-09-02 at the Wayback Machine, New England Center for International Law & Policy

- Микаелян, В.А. (1992). Докладная записка Карабахского армянского Национального Совета Правительству Армении о военных и политических событиях в Арцахе с декабря 1917 г. [Report of the Karabakh Armenian National Council to the Government of Armenia on the political and military events since December 1917, in Nagorno Karabakh in 1918–1923. Collection of Documents and Materials.]. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1971–1996). The Republic of Armenia. Vol. 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 176–178. ISBN 0-520-01805-2. OCLC 238471. Archived from the original on 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2022-07-04.

- Микаелян, В.А. (1992). Докладная записка Карабахского армянского Национального Совета Правительству Армении о военных и политических событиях в Арцахе с декабря 1917 г. [Report of the Karabakh Armenian National Council to the Government of Armenia on the political and military events since December 1917, in Nagorno Karabakh in 1918–1923. Collection of Documents and Materials.]. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences.

- Leeuw, Charles van der (2000). Azerbaijan : a quest for identity, a short history. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 120. ISBN 0-312-21903-2. OCLC 39538940. Archived from the original on 2023-01-13. Retrieved 2022-07-04.

- "The British administrator of Karabakh Col. Chatelword did not prevent discrimination against Armenians by the Tatar administration of Gov. Saltanov. The ethnic clashes ended with the terrible massacres in which most Armenians in Shusha town perished. The Parliament in Baku refused to even condemn those responsible for the massacres in Shusha and the war started in Karabakh. A. Zubov (in Russian) А.Зубов Политическое будущее Кавказа: опыт ретроспективно-сравнительного анализа, журнал "Знамья", 2000, No. 4, http://magazines.russ.ru/znamia/2000/4/zubov.html Archived 2019-03-25 at the Wayback Machine

- "massacre of the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh's capital, Shushi (called Shusha by the Azerbaijanis)", Kalli Raptis, "Nagorno-Karabakh and the Eurasian Transport Corridor", https://web.archive.org/web/20110716225801/http://www.eliamep.gr/eliamep/files/op9803.PDF

- "A month ago after the massacres of Shushi, on 19 April 1920, prime-ministers of England, France and Italy with participation of the representatives of Japan and USA collected in San-Remo..." Giovanni Guaita (in Russian) Джованни ГУАЙТА, Армения между кемалистским молотом и большевистской наковальней // «ГРАЖДАНИН», M., # 4, 2004 http://www.grazhdanin.com/grazhdanin.phtml?var=Vipuski/2004/4/statya17&number=%B94 Archived 2014-10-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Verluise, Pierre (April 1995), Armenia in Crisis: The 1988 Earthquake, Wayne State University Press, p. 6, ISBN 0814325270, archived from the original on 2023-01-13, retrieved 2022-07-04

- Tobias Debiel, Axel Klein, Stiftung Entwicklung und Frieden. [Fragile Peace: State Failure, Violence and Development in Crisis Regions]. Zed Books, 2002; p.94

- T.K.Oommen. Citizenship, nationality, and ethnicity Archived 2023-09-20 at the Wayback Machine. Wiley-Blackwell, 1997; p. 131

- Алла Ервандовна Тер-Саркисянц, Современная семья у армян Нагорного Карабаха. В: В.К. Гарданов (ed.). Кавказский этнографический сборник. Ter-Sarkisiants, A. A. "Sovremennaja semja u armjan Nagornogo Karabaxa". In: V. K. Gardanov (ed.). Kavkazskij ètnografičeskij sbornik, 6: 11-46; p. 34.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1971–1996). The Republic of Armenia. Vol. 2. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 187–189. ISBN 0-520-01805-2. OCLC 238471. Archived from the original on 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2022-07-04.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1971–1996). The Republic of Armenia. Vol. 3. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 162, 187–189. ISBN 0-520-01805-2. OCLC 238471. Archived from the original on 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2022-07-04.

- HRW Report on Soviet Union Human Rights Developments Archived 2020-11-11 at the Wayback Machine [in 1991]. Human Rights Watch, 1992.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1971). The Republic of Armenia: The First Year, 1918-1919, Vol. I. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 58–62. ISBN 0-520-01984-9.

- Hovannisian. Republic of Armenia, vol. I, p. 91.

- "Nakhchivan ASSR in the 1926 All-Soviet Census". Archived from the original on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 2011-06-12.

- Кавказский календарь на 1917 год [Caucasian calendar for 1917] (in Russian) (72nd ed.). Tiflis: Tipografiya kantselyarii Ye.I.V. na Kavkaze, kazenny dom. 1917. pp. 178–237. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021.

- Tsutsiev, Arthur (2014), Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus, New Haven and London, ISBN 978-0-300-15308-8, OCLC 884858065, retrieved 2021-12-25

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Погромы армян в бакинской и елисаветпольской губерниях в 1918–1920 гг [Pogroms of Armenians in the Baku and Elisavetpol governorates in 1918–1920.] (PDF). Yerevan. 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-08-07. Retrieved 2022-08-23.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Baberovski, Yorg (2010). Враг есть везде. Сталинизм на Кавказе [The enemy is everywhere. Stalinism in the Caucasus] (in Russian). Moscow: Rossiyskaya politicheskaya entsiklopediya (ROSSPEN) Fond «Prezidentskiy tsentr B. N. Yeltsina». p. 144. ISBN 978-5-8243-1435-9. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022.

- "Implementation of the Helsinki Accords: Human Rights and Democratization in the Newly Independent States of the former Soviet Union" (Washington, DC: U.S. Congress, Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, January 1993), p. 118

- "AZERBAIJAN: THE STATUS OF ARMENIANS, RUSSIANS, JEWS AND OTHER MINORITIES" Archived 2010-11-22 at the Wayback Machine, INS resource information center, 1993

- European Commission against Racism and Intolerance "ECRI REPORT ON AZERBAIJAN (fourth monitoring cycle) Archived 2013-03-16 at the Wayback Machine." May 31, 2011. p. 30.

- "Armenia, Azerbaijan and Russia sign Nagorno-Karabakh peace deal". BBC News. 2020-11-10. Archived from the original on 2020-11-10. Retrieved 2021-10-06.

- "Azerbaijani subversive group kills mother and son in Hadrut". Public Radio of Armenia. Archived from the original on 2020-11-17. Retrieved 2021-10-06.

- "Azerbaijan: Armenian POWs Abused in Custody". Human Rights Watch. 2021-03-19. Archived from the original on 2022-04-24. Retrieved 2021-10-06.

- "Nineteen Armenians 'killed in Azerbaijani captivity'". OC Media. 2021-05-04. Archived from the original on 2021-10-06. Retrieved 2021-10-06.

- "Two men beheaded in videos from Nagorno-Karabakh war identified". The Guardian. 2020-12-15. Archived from the original on 2021-10-05. Retrieved 2021-10-06.

External links

- Armenia.az Azerbaijan's Armenia site in Armenian