Architecture of Melbourne

The architecture of Melbourne, the capital of the state of Victoria and second most populous city in Australia, is characterised by a wide variety of styles dating from the early years of European settlement to the present day. The city is particularly noted for its mix of Victorian architecture and contemporary buildings, with 74 skyscrapers (buildings 150 metres or taller) in the city centre, the most of any city in the Southern Hemisphere.

In the wake of the 1850s Victoria gold rush, Melbourne entered a lengthy boom period, earning the moniker Marvellous Melbourne to represent its wealth and grandeur.[1] By the 1880s, it had become one of the largest and wealthiest cities in the British Empire, second only to London.[2] The wealth generated during this period is reflected in much of the city's grand, richly ornamented Victorian architecture, as well as the height of some buildings, with the 12-story APA Building (1889) rivalling other early skyscrapers in the American cities of Chicago and New York City.[3] Numerous villas and mansions sprung up in the suburbs, served by an expanding railway system, and a cable tram network. The interwar period saw many commercial additions to the city streets in a variety of styles, and the further spread of suburban housing.

The post WW2 period ushered in a new boom, with the city hosting the 1956 Summer Olympics, and the lifting of height limits at the same time led a boom in high rise office building, beginning with ICI House. This boom saw the loss of some of Melbourne's most remarkable Victorian buildings, notably the Federal Coffee Palace and APA Building, in the 1960s and 70s. Concern at the losses led to the establishment of the Victorian Heritage Register in 1974, and the heritage list now includes such places as the Royal Exhibition Building, the General Post Office, the State Library of Victoria and Flinders Street railway station.

Since the 2000s, the central city and Southbank area has seen a new boom in high rise construction, with some blocks of the city developed to very high densities, and the tallest buildings in Australia, including the 297m (92 floors) Eureka Tower, which was the tallest residential tower in the world when completed in 2006.[4]

The juxtaposition of old and new has given Melbourne a reputation as a city of no characterising architectural style, but rather an accumulation of buildings dating from the present back until the European settlement of Australia.

History

Settlement

Melbourne was first settled by Europeans in 1835, when rival entrepreneurs from Tasmania, John Batman and John Pascoe Fawkner sent expeditions looking for sheep pasture. Batman famously stated that “This is the place for a village”, generally believed to refer to the point on the Yarra River where freshwater was found (near today's Queensbridge).[5] The land to the north of the Yarra was a gentle valley between hills to the east and west, and riding ground to the north. In 1837, government surveyor Robert Hoddle laid out a grid of streets, approximately 30 metres wide (considerably wider than Sydney streets) between the two hills and aligned with the river.[6] Until the 1850s, the settlement of Melbourne grew at a moderate but steady pace.

Boom era (1850s–1890s)

Following this early settlement period, just after the state of Victoria was separated from NSW in 1851, gold was discovered, and thousands of people flocked to the city from the United Kingdom, as well as Europe and the United States, to seek their fortune on the Victorian goldfields. As a result of the Gold Rush, Melbourne's population grew from 4,000 in 1837 to 300,000 in 1854.[7] Approximately £100 million worth of gold was discovered in the Victorian fields in the 1850s.[7] Thanks to the immense wealth generated, many large public buildings were built or begun including the State Library, Parliament House, the Town Hall, and the General Post Office. The gold rush was followed by a growth in pastoral wealth, the development of local industries, railways, suburbs, shops, and ports.

The 1880s saw the price of land start to boom, and London banks were eager to extend loans to men of vision who capitalised on this by speculation, and grand, elaborate offices, hotel and department stores in the city, and endless suburban subdivisions. This was the growth that so astonished visiting journalist George Augustus Sala in 1885, that he dubbed the city "Marvellous Melbourne".[8][9][10]

Though many of the largest commercial buildings constructed during the 1880s Boom have been lost, many other fine examples still stand today, including the Royal Exhibition Building, the Gothic Bank (1883), the Hotel Windsor (1884), the Venetian Gothic Old Stock Exchange (1888), and Twentyman & Askew's 'high-rise' Stalbridge Chambers (1890).[13][14]

1900s–1940s: Edwardian to Art Deco

.jpg.webp)

The turn of the century in Melbourne marked the federation of Australia in 1901. The 1880s landboom had been followed by an equally large crash, the collapse of building societies and some banks, and an almost complete halt in construction by 1893. Sydney fared somewhat better, grew faster, and overtook Melbourne in size and population by 1901.[15][16] Melbourne remained important thanks to its status as Australia's (interim) capital city, the home of the Commonwealth of Australia. The Victorian Parliament House on Spring Street was handed over to house the parliament of Australia, while the Victorian parliament moved to the Exhibition Buildings. Economic revival in the 1900s saw a resurgence of construction. In this period, architects began to look less to England for inspiration, and more to the United States, particularly the Romanesque Revival.[17]

A major landmark of this period was built when it was finally decided to replace the ad hoc collection of train sheds Flinders Street Station with a grand terminus. A competition was held in 1899, with 17 entries received.[18] The competition was essentially for the detailed design of the station building, since the location of the concourse, entrances, the track and platform layout, the type of platform roofing and even the room layout to some extent was already decided.[19] The first prize, at £500, went to railway employees James Fawcett and HPC Ashworth of Fawcett and Ashworth in 1899. Their design, titled Green Light, was of French Renaissance style and included a large dome and tall clock tower.[18] The train shed over the platforms was intended to have many arched roofs running north-south, but this was never built. Over the next few years, the design was altered with an additional floor, and work on the station building itself began in 1905. Ballarat builder Peter Rodger was awarded the £93,000 contract and the station was originally to be clad in stone, but this exceeded the allocated budget.[18] Red brick with cement render was chosen for the Edwardian style building. Work on the dome began the following year, and delayed construction saw a Royal Commission appointed in May 1910. The Way and Works Branch of the Victorian Railways took over the project, the station being essentially finished by mid-1909. The verandah along Flinders Street and the concourse roof and verandah along Swanston Street were not completed until after the official opening in 1910.[20] The building has been repainted five times in its history, and the last repaint occurred in 2017. The most recent paint job was conducted to match the original colours as closely as possible, obtained through numerous samples of chipped paint which revealed the original colours after being cut in a polyester resin tube.[21]

From 1905 there was much debate about the merit of taller buildings in the city centre, and the idea of a height limit, influenced by the City Beautiful movement, gained popularity. There was also a concern to preserve light and air at lower levels, especially in the ‘little’ streets. Eventually, as part of a suite of rules that also ensured fire proof construction, the City of Melbourne passed a byelaw mandating a 132 ft limit.[22][23] It was (and still is) popularly believed that this was as high as fire ladders could reach, but in fact the longest ladder was 87 ft, and the limit was based on proportions, being 1+ 1/3 times the 99 ft main street width.[24] This limit stayed in force until the late 1950s, ensuring an evenness to many built up streets.

The styles of the early 20th century included Federation architecture, Stripped Classical, and then art deco. The rise of the suburbs in Melbourne meant that large acres of land could be purchased and homes could be designed in appointed styles of the land owners and home builders. One of the most popular styles was art deco, and several public city buildings were designed in this style, including the Manchester Unity Building, which mixed art deco with Gothic Revival. The building was constructed in 1932 by the Manchester Unity I.O.O.F. in Victoria.[25] Other buildings in the art deco style include the Myer Emporium (1920), T & G Building (1929), the Australasian Catholic Assurance Building (1935) and Mitchell House (1937)–which more closely resembles the Streamline Moderne style.[26] These contemporary styles mirrored an increasingly diversifying city, which reflected the changing international architectural fashions. The Second World War saw a halt to construction by 1942. By the late 1940s, Melbourne boasted an array of styles the eras in which it prospered, including Victorian, Gothic, Queen Anne and the most flourishing style of the early 20th century–art deco.

1950s–70s: Modernist attitudes

The arrival of the 1950s saw contemporary high rise offices constructed and the ICI House, built in 1955, was Australia's tallest building at the time.[27] ICI House, breaking Melbourne's long standing 132 ft height limit, was the first International Style skyscraper in the country.[27] It symbolised progress, modernity, efficiency and the booming corporate power in a postwar Melbourne. Its development also paved way for the construction of other modern high-rise office buildings, thus changing the shape of Melbourne's already diverse urban centre. Melbourne was the first city in Australia to undergo a post-war high-rise boom beginning in the late 1950s, though Sydney in the following decades built more, with over 50 high-rise buildings constructed between the 1970s–90s.[28][29] The 1950s and 1960s was a period before heritage controls were enacted, and many commentators now view these years of rampant demolition as one akin to urban vandalism.[30] Whelan the Wrecker, the most successful demolition company, was responsible for most of the destruction of Melbourne's historic buildings. A vast number of city hotels also closed in the 1950s, as a result of blighting liquor laws, which meant that the cost of running a licensed venue outstripped the return.[31] This may have explained the dwindling patronage of Melbourne's grand hotels in the 1950s and 60s.

The tragedy of Melbourne’s modernity culminated in the destruction of 10 landmark buildings, whose architectural heritage rivalled many mid-town Manhattan gems.[32]

— Medium

Another venue that shaped Melbourne's early architectural form is the pub, a licensed drinking establishment traditionally built on corners within the inner-city and city centre, usually no more than two-storeys tall. In the 1920s, there were about 100 corner pubs in Melbourne but this figure diminished to 45 by the 1960s. Today there are approximately 12 operating in the CBD – including The Metropolitan, which is located on the corner of William Street, and first served beer in 1854.[33]

In 1972, as a result of sustained pressure from the National Trust, Victorian Parliament amended the Town and Country Planning Act to include the "conservation and enhancement of buildings, works, objects and sites specified as being of architectural, historical or scientific interest". The act went onto specify the prohibition of "pulling down", "removal" or "decoration or defacement" to any such building. Because only specified sites were to be protected, the local councils across Melbourne had the task of allocating buildings and places that warranted protection. The City of Melbourne council specified the entire CBD as an area of significance in 1973. However, this blanket protection measure came unstuck in 1975 when the council was threatened with compensation payments to developers if their plans were rejected on heritage grounds, and the issue of compensation was not settled until 1982. At the same time, the Historic Buildings Preservation Act was passed in 1974, protecting at first only 100 places across the state. This was soon expanded to include many of the central city’s finest buildings, though only a handful of the commercial landmarks, and listing did not necessarily ensure preservation. In this context, as well as the many places demolished in the 1960s sometimes without a plan for a replacement, "developers white elephant schemes for central Melbourne proceeded virtually unchecked throughout the 70s", resulting in widespread loss of historic buildings.[34] Heritage listing by the City of Melbourne did not properly occur until 1982, with the listing of about 300 Notable buildings, and large areas declared Heritage Precincts,[35] with the added protection of the re-imposition of the height limit in the central retail area between Russell and Elizabeth Streets, and much lower limits in places such Chinatown, Bourke Hill, and Hardware Lane, which was also pedestrianised.

Controversy arose in 2016 after the historic Corkman Irish Pub in Carlton was illegally demolished overnight by developer Raman Shaqiri, resulting in the State Planning Minister pursuing an order (via the Victorian Administrative Appeals Tribunal) for the two-storey pub to be rebuilt.[36] The site owners were fined AUD$1.325 million after pleading guilty to the process. The site of the pub, which was built in 1858 and was once called the Carlton Inn Hotel, is currently a temporary carpark.[37]

Skyscraper boom

Between the late 1970s and 1980s, Melbourne's skyline reached new heights with the construction of several office buildings. Whelan the Wrecker went out of business in the early 1990s and heritage laws were tightened into the mid 1990s. In 1972, 140 William Street (formerly known as BHP House) became the city's first building to exceed the height of 150 metres and was the tallest in Melbourne for a few years. It was constructed in steel and concrete and features an imposing dark glass facade. Designed by the architectural practice Yuncken Freeman alongside engineers Irwin Johnson and Partners, it was heavily influenced by contemporary skyscrapers in Chicago. The local architects sought technical advice from Fazlur Khan of renowned American architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), spending 10 weeks at their Chicago office in 1968.[38] The design ingenuity of 140 William Street was recognised as the building became one of the few heritage registered skyscrapers in Melbourne.[39]

The Optus Centre, which surpassed 140 William Street's height marginally, was completed in 1975. In 1977 Nauru House claimed the feat of the tallest building in Melbourne at a height of 182 metres (7,200 inches)1978, the first of the Collins Place towers was opened, at a height of 185 metres. The design of Collins Place was based around a pair of towers at 45 degree angles to the Hoddle Grid, with the triangular spaces between forming an open plaza to the street and a shopping plaza behind the towers. All open spaces are covered by a space frame, with transparent plastic roofing. The whole complex is clad in tan-coloured precast masonry panels. In 1986, the Rialto Towers surpassed Sydney's MLC Centre as the tallest building in the Southern Hemisphere, with a height of 251 metres. At the time of its opening it was the 23rd–tallest building in the world.[40] In the 1990s, another 9 buildings were constructed in Melbourne that exceeded 150 metres; 5 of these surpassed heights of 200 metres. 101 Collins Street, which is 260-metre-tall (850 ft), became the tallest building in Australia and the Southern Hemisphere in 1991; it was surpassed in height as a result of the completion of the nearby 120 Collins Street that same year.[41] The skyscraper, which stands at 265 metres in height, held the titles for tallest building in Australia and the Southern Hemisphere for fourteen years, until the completion of the Gold Coast's Q1 in 2005.

Between 1996 and 97, a less admired Melbourne building became a target of demolition: the streamlined modernist Gas and Fuel Buildings. These structures were built in the late 1960s at a time when modernisation of the city was considered favourable.[42] The two towers, designed by Perrot and Parents, were also known as the Princes Gate Towers. As public opinion swayed back towards the desirability of 19th century heritage, the modernist Gas and Fuel Towers grew to be seen as "ugly and featureless", with no connection to the heritage that surrounded. The Kennett Government's decision to demolish the modernist towers was generally met with approval, and the towers were demolished to make way for Federation Square.[42] A similar fate was met by Hotel Australia, built in a Functionalist/Moderne style in 1939 and demolished in 1989.[43] In 2008, one of the last remaining Victorian arcades in the Melbourne CBD was demolished under approval from the planning minister at the time Matthew Guy. The decision and the rapidity of the demolition created public outrage.[44] The building, Eastern Arcade and Apollo Hall, built in 1872, was constructed on the site of the old Haymarket Theatre. It was the third arcade to be built in Melbourne and larger than both Queen's Arcade and the Royal Arcade. The Eastern Arcade was designed by George Johnston and had 68 stores as well as an upper storey. Despite discussions held by the Melbourne City Council to preserve the building or at least its facade, the entire structure was torn down in 2008.

Collins Place

Collins Place 120 Collins Street

120 Collins Street 530 Collins Street

530 Collins Street Rialto Towers

Rialto Towers

New millennium architecture

The new millennium saw a tighter attitude towards heritage conservation and a construction boom in Melbourne. On the back of Australia's financial and mining booms between 1969 and 1970, and the establishment of the headquarters of many major companies in the city, resulted in a continual rise in large, modern office buildings being constructed outside of the historic CBD and in newer precincts like Southbank and Docklands to preserve heritage overlays within the city centre.

The 2000s saw a continuation of skyscrapers and tall buildings with the urban renewal opening of the Melbourne Docklands in 2000 and the construction of Eureka Tower, an apartment building which is currently Melbourne's second–tallest skyscraper and the 77th tallest in the world at 92 floors and 297 metres.[45] The glass style building was constructed by Fender Katsalidis Architects. Australia 108 is currently Melbourne's tallest building and the tallest in Australia to its roof, completed in June 2020.[46]

Eureka Tower, Melbourne's second tallest building

Eureka Tower, Melbourne's second tallest building Australia 108 at Southbank

Australia 108 at Southbank Atrium inside Federation Square

Atrium inside Federation Square Apartments in St Kilda

Apartments in St Kilda.jpg.webp) Garden Building, RMIT University

Garden Building, RMIT University

Monuments and structures

Melbourne's metropolitan area is dotted with structures and memorials dedicated to various different historical events of significance. Perhaps the most notable, located in Kings Domain, is the Shrine of Remembrance, an art deco monument originally built to honour the men and women who served in the First World War, but now seen as a symbol for all Australians involved in war. Designed by architects and World War I veterans Phillip Hudson and James Wardrop, the Shrine is built in a classical style and is based on the Tomb of Mausolus at Halicarnassus and the Parthenon in Athens, Greece.[47] The defining element located at the top of the memorial's ziggurat roof is based on the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates. Constructed using Tynong granite,[48] the building once consisted only of the main sanctuary which was surrounded by the ambulatory. The sanctuary contains the marble Stone of Remembrance, which features an inscription stating "Greater love hath no man". Beneath the sanctuary lies a crypt, which contains a bronze statue of a soldier father and son representing two generations, as well as panels listing every unit of the Australian Imperial Force.

Federation Square, built on a concrete deck above railway lines, covering an area of 3.2 hectares (7.9 acres), is a mixed-used development built in the early 2000s. The buildings in the square were designed in a deconstructivist style with modern minimalist shapes. The complex of buildings forms a rough U-shape around the main open-air square, oriented to the west. The eastern end of the square is formed by the glazed walls of The Atrium. While bluestone is used for the majority of the paving in the Atrium and St. Paul's Court, matching footpaths elsewhere in central Melbourne, the main square is paved in 470,000 ochre-coloured sandstone blocks from Western Australia[49] and invokes images of the Outback. The paving is designed as a huge urban artwork, called Nearamnew, by Paul Carter and gently rises above street level, containing a number of textual pieces inlaid in its undulating surface. The square also contains a large television screen, which has broadcast a number of national addresses, including a 2007 speech from then Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, making an apology to the Stolen Generation of indigenous Australians. The square houses the Australian Centre for the Moving Image and the SBS Headquarters.

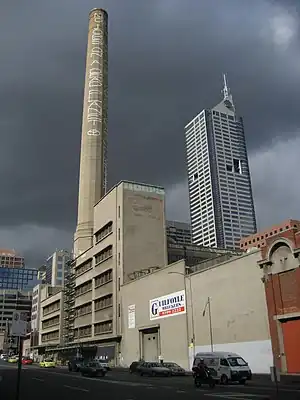

Several other famous structures and monuments outside the CBD, many of them located in beachside suburbs like St Kilda, were demolished or destroyed by fire. The dance hall Palais de Dance (1913) in St Kilda, built by Americans Leon and Herman Phillips, was destroyed by fire in 1968,[50] Princes Court (late 1800s), featuring toboggan and a water chute, was closed in 1909, the St Kilda Sea Baths, featuring two large bathing houses, was built in 1860 and closed in 1993. The famous Spencer Street Power Station in the city centre, featuring a large 370-feet chimney (built in 1952), and widely considered an "eyesore", was demolished between 2008 and 2009.[50]

Town halls and civic centres

Each municipality in Melbourne is represented by its own town hall.[51] The City of Melbourne's central municipal building is located on the northeast corner of Swanston and Collins Streets–it is the oldest town hall in Melbourne's metropolitan area, constructed in 1887 in Second Empire style, by the iconic local architect Joseph Reed and Barnes. The building is topped by Prince Alfred's Tower, named after the Duke. The tower includes a 2.44 m diameter clock, which was started on 31 August 1874, after being presented to the council by the Mayor's son, Vallange Condell. It was built by Smith and Sons of London. The longest of its copper hands measures 1.19 m long, and weighs 8.85 kg. The Main Auditorium includes a magnificent concert organ, now comprising 147 ranks and 9,568 pipes. The organ was originally built by Hill, Norman & Beard (of England) in 1929 and was recently rebuilt and enlarged by Schantz Organ Company of the United States.

South Melbourne Town Hall, which represented the now amalgamated areas of South Melbourne, Port Melbourne and St Kilda, is one of the second oldest town hall's and civic centres built in Melbourne, completed in 1879 in an elaborate Victorian Academic Classical style with French Second Empire features, dominated by a very tall multi-stage clock tower. The building is on the Victorian Heritage Register.[52]

Arcades and laneways

The many laneways and arcades of Melbourne have become internationally famous. Not only to they boast national cultural significance in Australia, but they have come to collectively represent Melbourne. The abundance of lanes in the Melbourne city centre reflects the town planning of Melbourne–the Hoddle Grid, they originated as service laneways for horses and carts.[53] In some parts of the city, notably the Little Lonsdale area, they were associated with the city's gold-rush era slums. Notable laneways include Centre Place and Degraves Lane. Melbourne's numerous shopping arcades reached a peak of popularity in the late-Victorian era and in the interwar years. These notably include Block Place and Royal Arcade. Some notable demolished arcades include Coles Book arcade and Queens Walk arcade. Cathedral Arcade, in the Nicholas Building (1927), was built in the art deco style and reflects Melbourne's 1920s architecture with glass domes, leadlight, arches, and shopfronts with detailed wood paneling.

Since the 1990s Melbourne's lanes, particularly the pedestrianised ones, have gentrified.[54][55][56] Officialdom has recognised their heritage value, and they attract interest from Australia and around the world. Some of the lanes have become particularly notable for their acclaimed urban art.

Bridges

Melbourne's positioning spanning the Yarra River, and on the coast, necessitates several water crossings. Bolte Bridge, Australia's longest bridge, is a large twin cantilever bridge that spans the Yarra, and Victoria Harbour in the Docklands, to the west of the Melbourne central business district. Bolte Bridge was designed by architects Denton Corker Marshall from 1996 to 1999 at a cost of $75 million. The bridge features two 140 metre[57] high silver (grey concrete) towers, situated on either side of the roadway at the midpoint of the bridge's span. These two towers are an aesthetic addition by the architects, and are not joined to the main body of the bridge.[57] Several other pedestrian bridges that cross the Yarra River, connecting Southbank to the Melbourne city centre were built between the 19th-century and the 1990s. The most notable early multi-purpose crossing of the Yarra is the Princes Bridge, constructed in 1888.[58] A more recent example of a bridge crossing over the Yarra is the Evan Walker Bridge, completed in 1992.

The wrought-iron arch Queens Bridge, one of the oldest remaining bridges in the city, was constructed in 1889 has five wrought iron plate girder spans, and is listed on the Victorian Heritage Register.[59][60][61] The bridge was built by contractor David Munro, and replaced a timber footbridge built in 1860.[62][63] The Morell Bridge, built in 1899, is notable as the first bridge in Victoria that was built using reinforced concrete.[64][65][66][67] The bridge features elaborate decorations on the three arch spans, including prominent dragon motifs as well as ornamental Victorian lights. The gutters on the bridge are cobbled bluestone, with a single lane bitumen strip running down the middle. The Bridge is listed on the Victorian Heritage Register.[68]

Residential architecture

Like many other Australian capital cities, Melbourne's suburbs and residential architecture has been shaped by the city's extensive history–thus it is defined by a variation in style, ranging from elaborate Victorian properties to more contemporary postwar homes. To counter the trend towards low-density suburban residential growth, the government began a series of controversial public housing projects in the inner city by the Housing Commission of Victoria, which resulted in demolition of many neighbourhoods and a proliferation of high-rise towers.[69]

Upper class suburbs like Toorak flourished during Melbourne's gold rush era and feature remnants of the prosperous past, as does South Yarra, Malvern and various other eastern suburbs. These areas have Tudor, Tudorbethan, Georgian and Victorian architecture in abundance, among many other styles. More middle class areas like Camberwell and Caulfield are characterised by Bungalows. American architects like Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Sullivan have also had influence on the residential style of Melbourne.[70]

Goodrest Mansion, South Yarra

Goodrest Mansion, South Yarra Raheen Tower, Kew

Raheen Tower, Kew Chastleton House, Toraak

Chastleton House, ToraakStonnington_mansion.jpg.webp) Stonnington Mansion, Malvern

Stonnington Mansion, Malvern

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Melbourne's Oriental Bank, circa 1870. The building was demolished in the 1890s.

Melbourne's Oriental Bank, circa 1870. The building was demolished in the 1890s.

Safe Deposit Building

Safe Deposit Building Alstons Building

Alstons Building Gothic Revival ANZ Bank building on Collins Street and Queen Street

Gothic Revival ANZ Bank building on Collins Street and Queen Street St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral

Parliament House Melbourne

Parliament House Melbourne Ornate detail of the Block Arcade (1892)

Ornate detail of the Block Arcade (1892)

A.C. Goode House (1891)

A.C. Goode House (1891) Gothic and Victorian buildings on Collins Street

Gothic and Victorian buildings on Collins Street

Stalbridge Chambers (1889), one of only two remaining historic Melbourne skyscrapers

Stalbridge Chambers (1889), one of only two remaining historic Melbourne skyscrapers

See also

References

- "Cultural Cringe and 'The Lost City of Melbourne'". The New York Times. 16 September 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- Cowan, Henry J. (1998). From Wattle & Daub to Concrete & Steel: The Engineering Heritage of Australia's Buildings. p. 160. ISBN 9-780-52284730-7.

- "New Buildings in Melbourne: The Loftiest Structures in the City". The Argus. 14 June 1888. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- "100 Tallest Residential Buildings in the World". Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- "The Founding of Melbourne, 1835". Museum of Victoria. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "City of Melbourne — Roads — Introduction". City of Melbourne. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- Chapman & Stillman 2014, pp. 7.

- Davison 1978.

- "A History of the City of Melbourne's Urban Environment" (PDF). Government of Victoria. 12 June 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "Marvellous Melbourne | State Library Victoria". www.slv.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Australian Property Investment Co. Building". National Trust Database. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "Global status for our greatest building", 21 October 2002. URL accessed on 5 September 2006.

- Goad 2012, pp. 543.

- "Stalbridge Chambers – 435-443 Little Collins Street". Walking Melbourne. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Pennsylvania State University 1990, pp. 60.

- "Marvellous Melbourne – 1880s". Museum of Victoria. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Griffiths 2014, pp. 77.

- "Flinders Street Station: History of a Melbourne icon". Herald Sun. 10 November 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Davies 2008, p. 20.

- Davies 2008, p. 38.

- "Flinders Street Station's new colours 'as close as possible' to original look thanks to science". ABC. 10 November 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "CITY BUILDING REGULATIONS". Age. 24 February 1916. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- School of Historical Studies, Department of History. "Skyscrapers - Entry - eMelbourne - The Encyclopedia of Melbourne Online". www.emelbourne.net.au. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- "The Limited City - Building Height Regulations in The City of Melbourne, 1890-1955 by Peter Mills 1997 | PDF | Melbourne | Elevator". Scribd. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- "Manchester Unity Building". The Age. Melbourne. 1 September 1932. p. 6. Retrieved 24 January 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Mitchell House". Victorian Heritage Database (VHD). Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- Australian National Heritage listing for the ICI Building

- "Time Series Analysis of the Skyline and Employment Changes in the CBD of Melbourne" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- "Melbourne Timeline Diagram". Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- Chapman & Stillman 2014, pp. 88.

- Annear 2005, pp. 280.

- "Lost Melbourne: 10 Landmark Buildings Demolished Forever". Medium. 2 March 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- Lucas, Clay (7 June 2018). "Planning laws see speculators target last pubs standing on CBD corners". The Age. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Annear 2005, pp. 358.

- School of Historical Studies, Department of History. "Heritage Conservation - Entry - eMelbourne - The Encyclopedia of Melbourne Online". www.emelbourne.net.au. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- "Once a building is destroyed, can the loss of a place like the Corkman be undone?". The Conversation. 19 March 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "Corkman Pub site to become temporary park after deal struck with 'cowboy developers'". ABC. 30 May 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "Former BHP House". 3 March 2000. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "Scraping the sky: Melbourne's tallest buildings since 1871". Herald Sun. 20 September 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Interactive Data – The Skyscraper Center Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- MacMahon, Bill (2001). "Melbourne". The Architecture of East Australia: An Architectural History in 432 Individual Presentations. Edition Axel Menges. pp. 171–72. ISBN 3-930698-90-0.

- Chapman & Stillman 2014, pp. 124.

- Chapman & Stillman 2014, pp. 110.

- Chapman & Stillman 2014, pp. 134.

- "Eureka Sky Deck". Archived from the original on 23 December 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- "Australia 108 officially becomes the tallest residential tower in Southern Hemisphere". 10 June 2020. Archived from the original on 17 June 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- Taylor 2005, pp. 101.

- Royall, Ian (11 December 2007). "Shrine of Remembrance's structure in the wars". Herald Sun. Retrieved 12 July 2008.

- "ABC OPEN: Melbourne's first public square". ABC. 28 June 2016. Archived from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Chapman & Stillman 2014, pp. 70.

- "Victorian Heritage Database". Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- "South Melbourne Town Hall". Victorian Heritage Database. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Bate, Weston (1994). Essential But Unplanned: The Story of Melbourne's Lanes. State Library of Victoria in conjunction with the City of Melbourne. ISBN 9780730635987. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- "Melbourne's Aesthetic Turn: Coffee Culture, Industrial Chic And Global-city Elites". arena.org.au. June 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- "Lessons from the laneways: a love letter to the 1990s". City of Melbourne. 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- "How Melbourne Found its Laneways". Broadsheet. 25 July 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- "Denton Corker Marshall: Bolte Bridge". Archived from the original on 4 March 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "Princes Bridge, Victorian Heritage Register (VHR) Number H1447, Heritage Overlay HO790". Victorian Heritage Database. Heritage Victoria.

- "Queens Bridge, Victorian Heritage Register (VHR) Number H1448, Heritage Overlay HO791". Victorian Heritage Database. Heritage Victoria. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- City of Melbourne. "Bridges of Melbourne: Bridge Management Plan" (PDF). www.melbourne.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- "OPENING OF THE QUEENS-BRIDGE". Illustrated Australian News And Musical Times. No. 420. Victoria, Australia. 1 May 1890. p. 19 (NEW ZEALAND EDITION.). Retrieved 16 August 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Queens Bridge (listing VICH1448)". Australia Heritage Places Inventory. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- "THE NEW QUEEN'S BRIDGE". The Argus. No. 13, 670. Melbourne. 17 April 1890. p. 9. Retrieved 16 August 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- City of Melbourne. "Bridges of Melbourne: Bridge Management Plan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- "The Monier Bridge". The Argus. Melbourne. 21 July 1899. p. 6. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- Morell Bridge at Structurae

- Kristin, Otto (2009), Yarra : a diverting history, Text Publishing, p. 190, ISBN 978-1-921520-00-6

- "Morell Bridge, Victorian Heritage Register (VHR) Number H1440, Heritage Overlay HO395". Victorian Heritage Database. Heritage Victoria.

- William, Logan (1985). The Gentrification of inner Melbourne: a political geography of inner city housing. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. pp. 148–160. ISBN 0-7022-1729-8.

- Goad, Phillip (1999). Melbourne Architecture. ISBN 094928436X.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

Literary references

- Annear, Robyn (2005). A City Lost & Found: Whelan the Wrecker's Melbourne. ISBN 978-1-45967-670-1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Chapman, Heather; Stillman, Judith (2014). Lost Melbourne. Pavilion. ISBN 978-1-910496-74-9.

- Davies, Jenny (2008). Beyond the Façade: Flinders Street, More than just a Railway Station. Publishing Solutions. ISBN 978-1-921488-03-0.

- Davison, Graeme (1978). The Rise and Fall of Marvellous Melbourne. Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-522851-23-6.

- Goad, Philip (2012). Encyclopaedia of Australian Architecture. Cambridge University Press. p. 543.

- Griffiths, Jessica (2014). Imperial Culture in Antipodean Cities, 1880-1939. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137385-73-4.

- Pennsylvania State University (1990). The history of the Liquor Trades Union in Victoria. Victorian Branch, Federated Liquor and Allied Industries Employees Union of Australia. p. 60.

- Taylor, William (2005). "Lest We Forget: the Shrine of Remembrance, its redevelopment and the heritage of dissent" (PDF). Fabrications. 15 (2): 102. doi:10.1080/10331867.2005.10525213. S2CID 162193990. Retrieved 12 July 2008.

.jpg.webp)