Andrew Johnson alcoholism debate

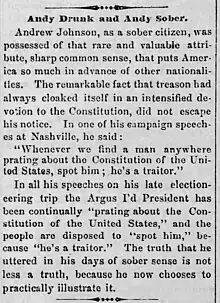

The Andrew Johnson alcoholism debate is the dispute, originally conducted amongst the general public, and now typically a question for historians, about whether or not Andrew Johnson, the 17th president of the United States, drank to excess. There is no question that Andrew Johnson consumed alcohol (as would have been typical for any Tennessean of his era and station), the debate concerns whether or not he was governing drunk, how alcohol may have altered his personality and disrupted his relationships, and if, when, or how it affected his political standing, and even his current bottom-quartile historical assessment. Less so today, but in his own time, Johnson's alleged drinking contributed substantially to how his peers evaluated his "attributes of mind, character, and speech. In each case, a particular standard is assumed to mark presidential virtue and is in turn used as a basis for vilifying Johnson. Thus, where the good ruler is temperate, Johnson is an inebriate; where the good ruler is selfless, Johnson is self-regarding; where the good ruler is eloquent, Johnson is a rank demagogue. Needless to say, there lurks behind all these assumptions the still and silent image of the Great Emancipator, but that is another story."[2]

All that said, the Andrew Johnson alcoholism debate may be a case of questions without answers. Per historian Annette Gordon-Reed, "We will probably never know the extent to which alcohol was a part of Johnson's life. Not all alcoholics appear drunk in public, and his relatively solitary existence—his family was almost never with him and he had few friends—was exactly the kind of setup that allowed for unobtrusive drinking that could become a problem in a time of great emotional and physical stress."[3]

We tell them we would sooner have Andy Johnson drunk than Jeff. Davis sober, or John Breckenridge either, if he could be ever found sober.

— Rev. Dr. Hancock's Temperance Address, New York, June 1865, Buffalo Advocate

Johnson's alcohol use

According to two histories of alcohol in the United States, the country had three alcoholic presidents during the 19th century: Franklin Pierce, Andrew Johnson, and Ulysses S. Grant.[4][5] A broad overview of the human use of intoxicants asserts that Johnson was thought to "be rarely sober."[6] A scholarly examination of the consequences of illness in national leaders states, "The best-known instance of alcohol abuse in high office is that of Andrew Johnson, whose alcoholism figured in the debate concerning his impeachment."[7]

"Drunkenness, of Johnson" has 16 mentions in Andrew Johnson: A Biographical Companion, which puts the topic on par with "Election of 1866" and "First Military Reconstruction Act."[8] The Biographical Companion, citing the editors of The Papers of Andrew Johnson and Hans Trefousse, states that all charges/claims of Johnson being drunk "were false except for one incident [the March 4 inauguration]...Johnson was not intoxicated. He was merely falling back into ingrained stump-speaking habits...His actions did not conform to many people's ideas about how a president should behave."[8] The most famous case of Andy drunk was at his 1865 inauguration as vice president of the United States under Abraham Lincoln, but it was not the first or the last time he appeared intoxicated in public, and per historian Elizabeth Moran, "He never lived these incidents down, although historians contend that they were greatly exaggerated."[9] As he set out on his Swing Around the Circle tour as president, a Pennsylvania newspaper summarized the general perception (amongst his enemies, at least) of the intersection of Johnson's drinking and his politics: "From the day that Andrew Johnson took his seat as Vice President of the United to the present moment he seems to have improved every opportunity to belittle himself and disgrace the position he holds, by either bacchanalian revels, or the retailing of vile slang in partisan speeches...His stooping to blackguard private citizens was thought to be lowest depth to which drunken recklessness could drag him down, but a lower depth has been found."[10] A 1916 thesis on Johnson's era as military governor of Tennessee argued, "The habit of indulging in intoxicants, afterwards reputed as Johnson's most conspicuous personal failing as President, had, of course, been formed long before. There is no evidence that it interfered seriously with the performance of his duties, but it occasionally betrayed him into extravagance of action and expression which did him no credit."[11]

Nonetheless, after examining recollections of Johnson by Vice President Hannibal Hamlin and Interior Secretary Carl Schurz, a historian of alcoholism found that Andrew Johnson most likely met the criteria for problem drinking, based on accounts that suggest he indulged in benders, drank in "enormous" quantities, gulped down hard liquor as if it were water, drank in the morning, drank after drinking, and consumed excessive, inebriating quantities of alcohol at inappropriate times.[5] The author, James Graham, argues that "ugly behavior is symptomatic," and states that "It's probable that [Johnson's] alcoholism-driven ego played a more important role in his clash with Congress, which led to the attempted impeachment, than alcoholism-ignorant modern historians realize."[5] He also argues that alcoholism is often "not noticed outside the home until the alcoholic reaches the advanced stage of the disease and starts showing the bizarre behavior associated with the condition—such as showing up drunk on the job."[5]

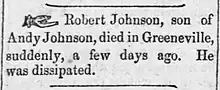

Additionally, while it is hardly evidentiary, it may be relevant that all three of Johnson's sons struggled with alcoholism, quite publicly in the case of Robert Johnson—he was in the New York State Inebriate Asylum at the time of Grant's inauguration.[12] Robert died of an overdose of alcohol and laudanum, but by some historians theorize that alcohol was also involved in the deaths of Charles and Frank, which are otherwise attributed to accident and tuberculosis, respectively.[13] Hans Trefousse, who wrote the most recent major biography of Johnson, argued, "...although his sons suffered from alcoholism, and he himself was constantly accused of it after his inauguration, it seems evident that, unlike a true alcoholic, Johnson could take or leave his liquor at will."[14]

Opinion of historians since 1900

| Historian | Year | Johnson alcoholic? | Notes, quotes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| James Schouler | 1906 | No[15] | ||

| Clifton Hall | 1916 | Yes[11] | ||

| Robert W. Winston | 1928 | No[16] | "Strangely enough, in the midst of such universal dissipation, Andrew Johnson was not overmuch afflicted with the drink habit." | |

| Lloyd Paul Stryker | 1929 | No[17] | "Like all truly temperate men he was abstemious in food as well as drink." | |

| George Fort Milton | 1930 | No[18] | No, per memoir of McCulloch | |

| Howard K. Beale | 1930 | ? | ||

| Paul Buck | 1938 | ? | ||

| Peter Levin | 1948 | ? | ||

| Milton Lomask | 1960 | ? | ||

| Fay W. Brabson | 1972 | ? | ||

| Eric L. McKitrick | 1961 | Drinking issue left largely unexamined[19] | Mentions apparent exoneration on charges of drinking round the circle | |

| Albert Castel | 1979 | Inconclusive | "...once again [Johnson] succumbed to oratorical self-intoxication..."[20] | |

| Hans L. Trefousse | 1989 | No[14] | ||

| Annette Gordon-Reed | 2011 | Inconclusive[3] |

Chronic alcoholic abuse or character flaws?

On the whole, historians seem to have concluded that Johnson's problems were not solely a consequence of whisky. W.E.B. DuBois described him as "drunk, not so much with liquor, as with the heady wine of sudden and accidental success."[21] However, "The Atlantic Monthly thought Johnson 'Egotistic to the point of mental disease,'"[2] and the two issues may have overlapped, as "Studies have shown links between narcissistic behavioral patterns and substance abuse issues."[22] In analyzing speeches that seemed like the drunken harangues of a half-deranged misanthrope, historians often find as much evidence for self-obsession as inebriation, as determined by audits of Johnson's favorite topic: himself. For example, in the official transcript of Johnson's vice-presidential inauguration speech, historian Stephen Howard Browne found "extraordinary use of the pronominal and possessive first person. In a speech of approximately 800 words, such constructions run to 28 'I's and nine 'my's. Indeed, in the first paragraph alone 'I' is deployed no less than 20 times. Now, a certain preoccupation with the self is no doubt to be expected under such circumstances, but as his audiences would learn soon enough, Johnson's phrasing here foreshadows an almost pathological fixation on his personal identity."[2]

Similarly, lowlights of the notorious Washington's Birthday speech of 1866 included its long duration, apparent ignorance of political reality, persecutory delusions, sullen resentment, thin-skinned "intolerance of criticism," egotism ("Who, I ask, has suffered more for the Union than I have?"), and more than 200 self-references.[23][24][25] Per historian Eric McKitrick in his ground-breaking Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction (1961), what the audience saw and heard was not the President under the influence of mind-altering substances but "Andrew Johnson the man, fully true to his themes of his career and character."[26]

Taste and preferences

According to Mint Juleps with Teddy Roosevelt: The Complete History of Presidential Drinking, "Andy Johnson may not have been a drunkard, but neither was he a stranger to whiskey. If one reads through his letters and bills, there is ample evidence that Johnson possessed a discernible taste for quality whiskey—and was willing to pay good money to get it."[27] A conflicting account of Johnson's taste comes from John B. Brownlow in an 1892 letter to Oliver Perry Temple: "Johnson was always perfectly indifferent to the quality of whiskey he drank, he smacked his lips and enjoyed the meanest whiskey hot and fresh from the still, with the fusil oil on it, and stuff that would vomit a gentleman..."[28] According to historian David Warren Bowen, Johnson's back-slapping, swill-chugging persona was part of a larger "almost pathetic appeal for acceptance".[28] According to DuBois, Johnson was known to consume "three or four glasses of Robertson's Canada Whiskey" per day.[21] Benjamin C. Truman, who was Johnson's personal secretary for a time during the American Civil War, said much the same, that Johnson pretty much only drank whiskey (he refused wine with meals and disliked champagne), he avoided bars and saloons, he preferred Robertson County-style Tennessee whiskey, and that four glasses a day was not unusual for him, although he didn't necessarily drink daily.[29] The recollections of Carl Schurz, M. V. Moore and others also suggest that Johnson would periodically isolate himself and go on multi-day binges.[30][31] The Johnson family may have used the term "spree" to describe such binge drinking.[16][31]

Public statements on drinking

As for Johnson's own testimony on the sale and consumption of alcohol, according The Curse of Drink: Or, Stories of Hell's Commerce:[32]

- "Taxation means representation, permission, protection and perpetuity. License money is a bribe and the acceptance of it by the United States is a national sin....You shall not press down upon the brow of American homes the crown of thorns platted by the hand of the liquor traffic; you shall not crucify man upon a cross of high license."[32]

- "The whiskey business is the poison vine which entwines itself around the oaks of our national prosperity, the noxious weed that has sprung up in the garden of American industries, the nauseating bilge-water in our glorious ship of state, the pest of all ages."[32]

Vice-presidential inauguration (March 4, 1865)

The incident that set the stage for almost all later evaluation of Johnson's drinking habits was his floridly drunk speech on the floor of the U.S. Senate on the occasion of his swearing-in as Vice President of the United States. Serious historians describe him as "plastered,"[2] and recount that he "humiliated himself before everyone of importance in Washington."[33]

Excuses were later made that Johnson had typhoid and his obvious intoxication was the result of medication, or that outgoing V.P. Hannibal Hamlin manipulated him into drinking to excess.[3]

These formulations ignore a salient fact: Andrew Johnson was a grown man and responsible for his actions. If he was seriously ill before one of the most important events in American political life—at perhaps the most critical juncture in the nation’s history—he should have taken better care of himself, and known that drinking multiple tumblers of whiskey was not a good idea. If he was the kind of person whom another man could ply with drinks against his will before he participated in what was, until then, the crowning achievement of his career, he was even less qualified to be president than he showed himself to be.

A contemporary account of Andrew Johnson's swearing-in as vice president, as published in the Lancaster, Penn. Intelligencer Journal from the "correspondent of the New York Herald, a person sufficiently mendacious to praise Lincoln profusely and ready to go so far as to call his inaugural address eloquent" (meaning that the Herald was known as a relatively liberal, pro-Republican news outlet) reads thus: "[The Senators began] to look at each other with significance as if to say, 'Is he crazy, or what is the matter?'...It was not only a ninety-ninth rate stump speech but disgraceful in the extreme...the Democratic senators leaned forward and appeared to be chuckling with each other at the figure made by the Republican Party through their Vice President-elect...the sentences so incoherent it is impossible to give an accurate report of the speech...("Who is the Secretary of the Navy?"—was then heard, in a voice of less volume. Someone responded 'Mr. Welles'.)...'Has he no friends?'...It is charitable to say that his condition was such that he was unfit to make a speech...The effort of the Vice President elect to go through with the form of reading the sentences [of the oath] as read by Mr. Hamlin was painful in the extreme. He stumbled, he stammered, he repeated portions of it several times over..."[34] He was also apparently too disoriented to administer the oath to incoming Senators, and did not return to the Senate after Lincoln's speech to conduct further business of the Senate.[34]

Johnson's biographer Hans L. Trefousse wrote that Johnson, loudly and theatrically pronounced, "I kiss this Book in the face of my nation of the United States."[14] A Cincinnati paper reported that he had "driveled over the Holy Book as he took the oath of office," and editorialized "This cannot be covered up as a private infirmity...Mr. Johnson made a similar exhibition of himself here, and we then refrained on commenting on it because we thought it might only be a lapse in the interval when he was free from public duties."[35] Rev. Henry Ward Beecher was apparently present, "He saw the Bible whirled by the incoming V.P. about his head, like a cap when a man gives three cheers...The spectacle of an inebriated Vice President hiccoughing out his oath of office furnished such a text for discourse on temperance as hardly turns up once in an age."[36] Someone working in the Ordnance Department wrote in a private letter to his father that Johnson had been "disgracefully drunk."[37]

Multiple accounts had it that the "reporters for the Congressional Globe are said to have been tampered with" in order to prevent the release of an accurate transcript.[38][34] According to the Andrew Johnson Biographical Companion, news reports of the content of the speech tended to itemize the topics as bullet points and/or assert that "there was so much noise in the galleries" that Johnson could not be heard.[8]

As for Lincoln, he apparently simply slumped down in his seat during the speech and closed his eyes, and later told his Treasury Secretary Hugh McCulloch not to worry about it: "I have known Andy Johnson for many years; he made a bad slip the other day, but you need not be scared; Andy ain't a drunkard."[3][lower-alpha 1] The New York World, meanwhile, read the entrails and saw augurs of doom: "And to think that only one frail human stands between this insolent clownish drunkard and the Presidency! May god bless and spare Abraham Lincoln! Should this Andrew Johnson become his successor, the decline and fall of the American republic would smell as rank in history as that of atrocious monsters in human shape as Nero and Caligula."[38]

The spectacle inspired a song performed at a theater on E Street:[18]

And there Great Andy Johnson got

And took a brandy-toddy hot,

Which made him drunk as any sot,

At the Inauguration.

And now to wipe out the disgrace,

The President has closed the place,

Where Andy Johnson fell from grace,—

At the Inauguration!

After the fact, Johnson retreated to the Silver Spring estate of the Blair family in Maryland, "where he recuperated and hid from the press."[8] He made no public appearances until April 3, when he made a speech in front of a Pennsylvania Avenue hotel about the fall of the Confederate capital.[8] There were rumors that he had been in a binge but he wrote letters explaining that he was in fact "prostrated" by typhoid.[8] According to James G. Blaine, Johnson returned to Washington from Maryland about April 9, 1865 and "when Mr. Johnson arrived from Fortress Monroe on the morning of April 10, and found the National Capital in a blaze of patriotic excitement over the surrender of Lee's army the day before at Appomattox, he hastened to the White House, and addressed to the unwilling ears of Mr. Lincoln an earnest protest against the indulgent terms conceded by General Grant."[39] In 1866, a newspaper account had it that Lincoln met with Johnson on April 11, 1865, forgoing a family carriage ride to take the meeting, and when he returned, "remarked with much apparent concern 'That miserable man; I cannot imagine the trouble he will cause during my second term of office.'"[40] According to the standard account, Johnson and Lincoln supposedly did not meet again until the afternoon of April 14. That night Lincoln was shot in back of the head by John Wilkes Booth; the 16th president died the following morning. Johnson's 42-day vice presidency would be the second-shortest V.P. term in American history.[8]

In the end, whether or not he exhibited clinically significant symptoms of alcoholism during his Presidency, after the March 4 spectacle at the U.S. Capitol, "it did not much matter what the truth was about his drinking habits. The truth that mattered was that he had set himself up, made himself vulnerable to charges of drunkenness at virtually every crisis that beset his late political career."[2]

Presidential inauguration (April 15, 1865)

In 1908, former U.S. Senator William Morris Stewart published his Reminiscences, and most of the 20th chapter of the book is devoted to the abbreviated second term of Abraham Lincoln. One of the Chapter XX subtitles is "How a drunken man was sworn in as President." Hans L. Trefousse, Johnson's most recent major biographer, discounts Stewart's account entirely, writing, "The falsity of these assertions is evident. Stewart's account of the swearing in is contradicted by most other contemporary sources, including a memorandum in the chief justice's papers prepared the next day. The fact that the president took his oath at a later time than eight in the morning is well attested by various newspapermen, who failed to see any sign of drunkenness or a hangover. Moreover, the cabinet meeting at noon, which Welles recorded in his diary as well as in other memoranda, is proof positive of Johnson's condition and whereabouts on the fifteenth."[14]

According to Stewart's telling, there were but three witnesses to Johnson's inauguration (Stewart himself, Chief Justice Chase, and Senator Foot of Vermont) and "all statements to the contrary are absolutely false."[lower-alpha 2] Stewart claimed that Johnson had been in a "half-drunken stupor" since he arrived in Washington, D.C. in "January or February" 1865 and continued drinking following the debacle at the Capitol, and made at least one speech to a "great crowd of street hoodlums and darkies congregated...about the City Hall steps. He was intoxicated...It was quite common for Johnson to make these open-air speeches; and as he delivered them whenever he had been drinking, naturally he became the most persistent orator in the capital."[41] Following the death of Abraham Lincoln, Chase, Foot and Stewart found Johnson in his rooms on the third floor of the Kirkwood.[41]

After some little delay Johnson opened the door and we entered. The Vice-President was in his bare feet, and only partially dressed, as though he had hurriedly drawn on a pair of trousers and a shirt. He was occupying two little rooms about ten feet square, and we entered one of them, a sitting-room, while he finished his toilet in the other. ¶ In a few minutes Johnson came in, putting on a very rumpled coat, and presenting the appearance of a drunken man. He was dirty, shabby, and his hair was matted, as though with mud from the gutter, while he blinked at us through squinting eyes, and lurched around unsteadily. He had been on a "bender" for a month.

According to Stewart, Johnson's response to the news that he was to be sworn in was "I'm ready."[41]

Then, per Stewart again, after going to find Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and informing him of the state of the President:[41]

Stanton and I were driven back to the Kirkwood House, and, accompanied by the coachman, we went directly to Johnson's room. He was lying down. We aroused him, dressed him as well as we could, led him down stairs, and put him in Stanton's carriage. We took him to the White House, and Stanton sent for a tailor, a barber, and a doctor. He had a dose administered, and the President was bathed and shaved, his hair was cut, and a new suit of clothes was fitted to him. He did not, however, get into a condition to be visible until late in the afternoon, when a few persons were permitted to see him to satisfy themselves that there was a President in the White House.

This account was disputed at length by Tennessee Congressman Walter P. Brownlow (a nephew of Johnson's old political enemy Parson Brownlow) in an article the following year. Brownlow had the article entered into the Congressional Record of February 25, 1909.[lower-alpha 3] Brownlow's rebuttals included:

- if the story were true it would have been revealed at the contentious impeachment hearings

- Johnson was always known to be an immaculate dresser (fact check: true),[14] so he couldn't have been disheveled that morning

- Johnson did not move into the White House until six weeks after Lincoln's death (fact check: true)[20] so he couldn't have been taken to the White House to be cleaned up and have meetings

- Salmon P. Chase was a "consistent member of church and it is defamation of his character to say that he would have consented to administer to Johnson the oath had he been in the condition Stewart falsely says he was."[42]

Brownlow also pointed to an account by Lincoln and Johnson's Treasury Secretary Hugh McCulloch that repeated the traditional account of Cabinet members and Senators and stated that Johnson's hand rested on Proverbs 22 and 23 when, "with all due solemnity," he took the oath.[43] McCulloch has been described as "the only real defender of Johnson."[15] James G. Blaine also repeats the standard version, although in his account, the swearing of the oath was attended by all of Lincoln's cabinet except Secretary of State Seward (who had been gravely wounded by the conspirators against Lincoln's government), meaning that Gideon Welles, John Palmer Usher, and William Dennison Jr. would also have been present.[39]

According to a 1928 biographer named Robert W. Winston, who was granted access to the Johnson papers by his grandson Andrew Johnson Patterson,[16] the newly elevated President kissed the Bible at verse 21 of Ezekiel 11.[16][lower-alpha 4]

According to historians Dorothy Kunhardt and Philip B. Kunhardt in 1965, "Stanton ran the country single-handedly for the first days after the assassination, and no one looked to the newly sworn-in Johnson to make decisions. Johnson merely received delegations at the Treasury Building, seemed to mention the name Lincoln very seldom, and assured people he would punish treason."[45]

Comment by contemporaries

- Representative Benjamin F. Butler, speaking at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, November 24, 1866: "As to the specification and evidence of the first charge of public drunkenness, if common uncontradicted fame speaks truly, and that it does in this instance, the blush at shame which mantles the cheek of every true American when the occurrence is mentioned, is the highest guaranty—then every Senator who witnessed the disgraceful stammering tongue of the Vice President as he mumbled his oath of office, and slobbered the Holy Book with a drunken kiss, will be at once the witness and judge, and to other like public and disgraceful exhibitions almost every depot and station master between Washington and St. Louis can give evidence."

- John Weiss Forney, writing as Col. Forney, Secretary of the United States Senate, writing "Anecdotes of the Vice Presidents" in 1878: "Schuyler Colfax was like Andrew Johnson in his stern personal integrity, but unlike him in the ultra moderation of his habits."[46]

- Methodist Episcopal Bishop Gilbert Haven, July 4, 1879: "The Martyr-President had left a drunken imbecile in power: obstinate, unreasoning, unreasonable, with only one saving quality—devotion to the Union."[47]

- Hugh McCulloch, Treasury Secretary to both Lincoln and Johnson, memoirs published 1888: "Mr. Johnson was especially intemperate as a speaker when defending his policy and replying to the severe criticism to which he was subjected, but not in the use of liquor. I had good opportunities for observing his habits, and my fears made me watchful. For six weeks after he became President, he occupied a room adjoining mine, and communicating with it, in the Treasury Department. He was there every morning before nine o'clock, and he rarely left before five. There was no liquor in his room. It was open to everybody. His luncheon, when he had one, was, like mine, a cup of tea and a cracker. It was in that room that he received the delegations that waited upon him, and the personal and political friends who called to pay their respects. It was there that he made the speeches which startled the country by the bitterness of their tone their almost savage denunciations of secessionists as traitors who merited the traitor's doom. So intemperate were some of these speeches, that I should have attributed them to the use of stimulants if I had not known them to be the speeches of a sober man, who could not over come the habit of denunciatory declamation which he had formed in his bitter contests in Tennessee. They were, like all of his subsequent offhand addresses, quite unsuited to his position as President. If he had been smitten with dumbness when he was elected Vice-President, he would have escaped a world of trouble. From that time onward he never made an offhand public speech by which he did not suffer in public estimation, but none of them could be charged to the account of strong drink. For nearly four years I had daily intercourse with him, frequently at night, and I never saw him when under the influence of liquor. I have no hesitation in saying that whatever may have been his faults, intemperance was not among them."[48]

- M.V. Moore, apparently an acquaintance of Johnson from Tennessee, writing in the Philadelphia Weekly Times, reprinted in the Memphis Public Ledger, 1891: "Let us see how he went into the mills of the gods—into that of Nemesis especially. The avenging angel visited not once, simply, but the scourge came to Mr. Johnson again and again. It is a sorrowful history, that of his family. Of the three bright, promising sons born to him all died victims of the same enemy that carried the illustrious father away—the bottle. One of the young men was a dear fellow who I knew and loved well. One day during the war he was toppled from his horse on the streets of Nashville, Tenn. He was picked up with a broken skull. Andrew Johnson himself went off on a 'big spree.' He had been in the habit of 'getting off his balance' (to use a milder phrase)—shutting himself up in his room, attended alone by a faithful servant. When in this condition, if aroused or approached by others, he would swear like a maniac, hurling huge anathemas at friend and foe alike."[31]

- Charles A. Dana, a once and future journalist working for the U.S. Department of War during the American Civil War, met Johnson when he was military governor of Tennessee, memoir published 1898: "So he brought out a jug of whisky and poured out as much as he wanted in a tumbler, and then made it about half and half water. The theoretical, philosophical drinker pours out a little whisky and puts in almost no water at all—drinks it pretty nearly pure—but when a man gets to taking a good deal of water in his whisky, it shows he is in the habit of drinking a good deal. I noticed that the Governor took more whisky than most gentlemen would have done, and I concluded that he took it pretty often."[49]

- Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz, in his recollections of Johnson as military governor, as published 1907: "Yet I could not rid myself of the impression that beneath this staid and sober exterior there were still some wildfires burning which occasionally might burst to the surface. This impression was strengthened by a singular experience. It happened twice or three times that, when I called upon him, I was told by the attendant that the Governor was sick and could not see anybody; then, after the lapse of four or five days, he would send for me, and I would find him uncommonly natty in his attire, and generally 'groomed' with especial care. He would also wave off any inquiry about his health. When I mentioned this circumstance to one of the most prominent Union men of Nashville, he smiled, and said that the Governor had 'his infirmities,' but was 'all right' on the whole."[30]

- U.S. Senator from New Hampshire and Assistant Treasury Secretary under Lincoln William E. Chandler described Andrew Johnson in 1907 as "not the drunken boor of the public fancy but...a mild-mannered, earnest, quiet, kindly man, who did surprisingly well in view of his antecedents and environments."[50]

- Tennessee governor and U.S. Senator William G. Brownlow, by way of Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, by way of Walter P. Brownlow, published in 1909: "As the editor of a Whig newspaper and a speaker in every political campaign we have had in Tennessee since Johnson's entrance into public life I have fought him so zealously that for twenty years we were not on speaking terms. I never failed to publicly denounce him for anything which I believed he did which I regarded as disreputable, as I certainly do the excessive use of liquor, but I never charged him with being a drunkard because I had no grounds for so doing. I do not mean to say that he was a total abstainer from the use of intoxicating drinks, as I have always been, and as I think every man should be, but I do mean that nobody in Tennessee ever regarded him as addicted to their excessive use."[42]

- William H. Crook, U.S. Secret Service, published 1910: "I very soon began to realize that the reports of his drinking to excess were, like many other slanders, without foundation. I will state here that during the years he was in the White House there never was any foundation for it...I saw him probably every day...and I never once saw him under the influence of liquor...No man whose wits were fuddled with alcohol could have done what he did in Tennessee and Washington. He drank, as did virtually most public men of the time, a notable exception being Mr. Lincoln. The White House cellars were well stocked with wine and whiskies, which he offered to his guests at dinner or luncheon, but in my experience he never drank to excess."[51]

- Ben C. Truman, private secretary to Johnson during the war, also war correspondent, later owned several newspapers, writing c. 1913: "But that Andrew Johnson was a drunkard is more difficult to disprove...But had not Johnson been a drinking man through his life? I have often been asked. Not to the extent the one incident implied. Indeed Johnson had been considered a temperate man in all things. I sat with him at the same table in Nashville at least once a day for eighteen months and never saw him take wine or liquor with any meal. He never drank a cocktail in his life, never was in a barroom, and did not care for champagne. He did take two or three or four glasses of Robertson county whiskey. Some days some days less, and some days and weeks no liquor at all. So as drinking went in Tennessee, Johnson would have been termed a strictly temperate man."[29]

Tennessee whiskey aging in barrels

Tennessee whiskey aging in barrels - Former U.S. Senator Chauncey Depew, memoirs published 1924: "President Andrew Johnson differed radically from any President of the United States whom it has been my good fortune to know. This refers to all from and including Mr. Lincoln to Mr. Harding...His weakness was alcoholism. He made a fearful exhibition of himself at the time of his inauguration and during the presidency, and especially during his famous trip 'around the circle' he was in a bad way."[52]

When Andy was really Governor of Tennessee to save money he boarded in a Livery Stable but since he is no Ass—though he "often felt his oats and oftener his rye"—he took his forage upstairs.

— Unsigned, Knoxville Daily Register, 1862[53]

Other allegations of public inebriation

- Moses speech at Nashville on the night of October 24, 1864; a historian writing in 1916 seemingly suggested that Johnson freed the slaves of Tennessee by fiat because he was drunk: "Johnson addressed the crowd at the capitol in a speech of which we have several highly colored and garbled reports, the most favorable of which does him no credit as a statesman. Rather, to have resorted to the devices of the demagogue to sway the ignorant and excited blacks, and his extravagances of expression suggest his too-constant friend, the whiskey bottle, as the inspiration of his unfortunate diatribe."[11]

- In 1866, Rev. Beecher reported that Samuel C. Pomeroy, a U.S. Senator from Kansas "had called at the White House and found the President, his son [and private Secretary Robert Johnson] and his son-in-law [U.S. Senator David T. Patterson] all drunk and unfit for business. When questioned about it, Pomeroy denied having said he had seen the President drunk, but he had seen Robert Johnson very much so."[13][18]

- According to the Biographical Companion "many people suggested" he was drunk when he made speech made in honor of Washington's birthday in 1866 "but Johnson was not intoxicated".[8][54] Johnson's sworn enemy in Congress, Benjamin F. Butler, agreed that he was sober on that occasion, stating, "Can there be anything more indecent and degrading to the office of the President of the United States than the exhibition made by Andrew Johnson on the 22nd of February last, for which there is, unfortunately for the honor of the country, not the apology that he was drunk?"[55]

- Per Milton in his 1930 Age of Hate, "The claim was made that the President had been 'dead drunk' when he made his Cleveland speech, although it was later proved at the impeachment trial that this charge was a slander."[18]

- Delaware newspaper in the midst of the Swing Around the Circle tour: "The Vice President is as incapable of appreciating the reparation which he owes to the country as he shows himself to be incapable of appreciating his own insult to the country. He is reported in the Washington telegrams to be indulging still another debauch. Nothing better is to be expected of him. These are the habits of his lifetime, they were known to the politicians who nominated him, they were proclaimed in the face of the party which elected him. It is idle to ask the stream to rise higher than its fountain."[56]

- In August 1866 a Kansas paper suggested that the true cause of Andrew Johnson's tears at accounts of the pro-Johnson 1866 National Union Convention was not merely a surfeit of maudlin patriotism but a surfeit of whiskey: "It has been, observed that men bordering upon a state of delirium tremens, are affected to tears by trivial circumstances, and in a manner to make them appear silly in the extreme. Is not A. Johnson in that fix?"[57]

- In a private letter to his father in October 1866, F. W. Drury of Alton, Illinois wrote of Johnson's recent Swing Around the Circle tour: "His speech, his drunken driveling slobbering harangue at the Southern Hotel at St. Louis was the straw that broke the camels back it was the most disgusting tirade that ever emanated from any man—it would have disgraced Ben Peake, or General Pomeroy. He was drunk, drunk!"[1]

- John S. Wise, a former U.S. Congressman and U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, recollecting approximately 1875, in his book published 1906: "My next sight of Mr. Johnson was probably a year or so later, shortly before his death. It was soon after his campaign before the Tennessee Legislature for the Senate. At that time his habits had become exceedingly dissipated, and one of his peculiarities was that he appeared to select very young men as his companions in his debauches. His headquarters were at the Maxwell House at that time...A band serenaded him and the street was thronged with an immense crowd, cheering and calling loudly for a speech. After a long delay the ex-President appeared upon the hotel balcony and acknowledged the compliment, but his condition was such that he was totally unable to speak coherently and, in fact, found difficulty keeping his feet. It was a pitiful sight to see him standing there, holding on to the iron railing in front of him and swaying back and forth, almost inarticulate with drink...It was a sight I shall never forget—the bloated, stupid, helpless look of Mr. Johnson, as he was hurried away from the balcony to his rooms by his friends and led staggering through the corridors of the Maxwell House...He died shortly after the occurrence just related."[59]

See also

- Historical reputation of Ulysses S. Grant § Drinking

- William A. Browning – American political staffer (1835–1866)

Notes

- Abraham Lincoln's uncle Mordecai had officiated Andrew Johnson's wedding to Eliza McCardle, and his cousin Mary Sophia was married to William R. Brown, a Greeneville merchant who later married Johnson's daughter Mary Johnson Stover, after both their first spouses had died. The Lincolns were also distantly related to Mary's first husband Daniel Stover.

- There is a strange paucity of eyewitness accounts of Johnson's swearing-in.

- Per Miller, Zachary A. (2022). False Idol: The Memory of Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction in Greeneville, Tennessee 1869-2022 (Thesis). Paper 4096. the article was originally published as Brownlow, Walter P. (September 1908). "Defense and Vindication of Andrew Johnson". The Taylor-Trotwood Magazine. p. 493.

- In the King James Bible this line reads, "But as for them whose heart walketh after the heart of their detestable things and their abominations, I will recompense their way upon their own heads, saith the Lord God."[44]

References

- "Andy Drunk and Andy Sober". The Weekly Free Press. September 22, 1866. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2023-05-08. Retrieved 2023-05-08.

- Browne, Stephen Howard (2008). "Andrew Johnson and the Politics of Character". In Medhurst, Martin J. (ed.). Before the Rhetorical Presidency. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. pp. 194–212. ISBN 978-1-60344-626-6. Retrieved 2023-07-30 – via Project MUSE.

- Gordon-Reed, Annette (2011). Andrew Johnson: The American Presidents Series: The 17th President, 1865-1869. Holt. pp. 85–90. ISBN 978-0-8050-6948-8.

- Peterson, J. Vincent; Nisenholz, Bernard; Robinson, Gary (2003). A Nation Under the Influence: America's Addiction to Alcohol. Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 978-0-205-32714-0.

- Graham, James (1994). Vessels of Rage, Engines of Power: The Secret History of Alcoholism. Lexington, Virginia: Aculeus Press. pp. xviii, 32–33, 150, 152–155. ISBN 978-0-9630242-5-1. LCCN 93-70831.

- Siegel, Ronald K. (2005). Intoxication: The Universal Drive for Mind-Altering Substances. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-59477-069-2.

- Post, Jerrold M.; Robins, Robert S. (1995). When Illness Strikes the Leader: The Dilemma of the Captive King. Yale University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-300-06314-1.

- Schroeder-Lein, Glenna R.; Zuczek, Richard (2001). Andrew Johnson: a biographical companion. ABC-CLIO biographical companions. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 36 (Blair), 88 (drunkeness of), 306–307, 360 (index). ISBN 978-1-57607-030-7.

- "Andrew Johnson: Family Life". Miller Center, University of Virginia. October 4, 2016. Archived from the original on 2023-03-21. Retrieved 2023-05-07.

- "National Humiliation". The Bedford Inquirer. September 7, 1866. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-09 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hall, Clifton Rumery (1916). Andrew Johnson, military governor of Tennessee. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 154 (Nashville 1864), 219.

- "Death of Robert Johnson". Elyria Independent Democrat. Elyria, Ohio. April 28, 1869. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-06-16 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bergeron, Paul H. (2001). "Robert Johnson: The President's Troubled and Troubling Son". Journal of East Tennessee History. Knoxville, TN: East Tennessee Historical Society. 73: 1–22. ISSN 1058-2126. OCLC 760067571.

- Trefousse, Hans L. (1989). Andrew Johnson: A Biography. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 34 (appearance), 190 (kiss Bible), 191 (drinking), 195 (inauguration). ISBN 9780393317428.

- Lenihan, Mary Ruth (1986). Reputation and history: Andrew Johnson's historiographical rise and fall (Master of Arts thesis). University of Montana. pp. 5 (McCulloch), 31 (Schouler). ProQuest EP36186.

- Winston, Robert W. (1928). Andrew Johnson, plebeian and patriot. New York: H. Holt and company. pp. v. (prefatory note), 104 (drinking), 125 (Charleston spree), 268 (Ezekiel) – via HathiTrust.

- Stryker, Lloyd Paul (1929). Andrew Johnson; a study in courage. New York: The Macmillan company. p. 209 – via HathiTrust.

- Milton, George Fort (1930). The Age of Hate: Andrew Johnson and The Radicals. Coward-McCann, Inc. pp. 150 (song), 335 (Pomeroy), 367 (Swing Round the Circle, Cleveland & St. Louis) – via Internet Archive.

- Eric L. McKitrick (1988). Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction. Oxford University Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-19-505707-2 – via Internet Archive.

- Castel, Albert (1979). The Presidency of Andrew Johnson. Regents Press of Kansas. pp. 33 (June 1865), 90 ("self-intoxication"). ISBN 978-0-7006-0190-5.

- DuBois, W.E.B. (1935). "Transubstantiation of a Poor White". Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1888. New York: Russell & Russell – via Internet Archive.

- Hochenberger, Kristy Lee (September 4, 2021). "The Addiction of Narcissism". Psychology Today. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- "Remembering the Craziest First Year for an American President". InsideHook. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- "The Politics of Andrew Johnson". historymatters.gmu.edu. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- "Andrew Johnson Archives". The Saturday Evening Post. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- Eric L. McKitrick (1988). Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction. Oxford University Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-19-505707-2 – via Internet Archive.

- Will-Weber, Mark (2014). Mint Juleps with Teddy Roosevelt: The Complete History of Presidential Drinking. Washington, D.C.: Regenery History. pp. 152 (whiskey orders). ISBN 9781621572107.

- Bowen, David Warren (1989). Andrew Johnson and the Negro. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. pp. 40 ("pathetic appeal"), 174 (note 35: Brownlow letter). ISBN 978-0-87049-584-7. LCCN 88009668. OCLC 17764213.

- "Andrew Johnson's Habits". The News and Observer. January 5, 1913. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-07-11.

- Schurz, Carl; Dunning, William Archibald; Bancroft, Frederic (1907). The reminiscences of Carl Schurz ... New York: The McClure Company. p. 196.

- "A. Johnson, Tailor - The Curtain Raises and Delusions as to His Real Character Dispelled". Public Ledger. Vol. 26. Memphis, Tenn. August 17, 1891. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-07-10 – via Newspapers.com.

- Shaw, Elton Raymond; Wooley, John G. (1910). The Curse of Drink: Or, Stories of Hell's Commerce; a Mighty Array of True And Interesting Stories And Incidents. Grand Rapids. pp. 491, 494 – via HathiTrust.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mukunda, Gautam (2022). Picking Presidents: How to Make the Most Consequential Decision in the World. University of California. pp. 101 (humiliation), 105 (tragedy). ISBN 9780520977037. LCCN 2021060597.

- "Morals of the Republican Party". Intelligencer Journal. March 7, 1865. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-04 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Country Disgraced by a Drunken Vice President". Portsmouth Daily Times. March 11, 1865. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-08 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Vice President's Critics". The Selinsgrove Times-Tribune. March 31, 1865. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-07-08 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Rev. Dr. Hancock's Temperance Address". The Advocate. June 15, 1865. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-05-08.

- "From New York World of March 7: Mr. Vice-President Johnson". Argus and Patriot. March 16, 1865. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-08 – via Newspapers.com.

- Blaine, James Gillespie (1884–86). Twenty years of Congress: from Lincoln to Garfield. Norwick, Conn.: Henry Bill Pub. Co. pp. 1, 8–9 – via HathiTrust.

- "Abraham Lincoln's Opinion of Andrew Johnson". Brownlow's Knoxville Whig. December 19, 1866. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- Stewart, William M.; Brown, George Rothwell (1908). Reminiscences of Senator William M. Stewart, of Nevada; ed. by George Rothwell Brown. New York: Neale Pub. Co. pp. 188–196.

- United States Congress (1909). Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the ... Congress. Vol. 43. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 3197–3201 – via Google Books.

- "Bible Gateway passage: Proverbs 22-23 - King James Version". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- "Bible Gateway passage: Ezekiel 11 - King James Version". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- Kunhardt, Dorothy Meserve; Kunhardt, Philip B. (1965). Twenty days : a narrative in text and pictures of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the twenty days and night that followed--the Nation in mourning, the long trip home to Springfield. Internet Archive. New York : Castle Books. p. 100.

- Col. Forney (December 7, 1878). "Anecdotes of the Vice Presidents". The Saturday Evening Review. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-07-13.

- "Haven on Grant: Extract from Bishop Haven's Oration at Woodstock". The Nebraska State Journal. July 17, 1879. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-07-09 – via Newspapers.com.

- McCulloch, Hugh (1888). Men and measures of half a century; sketches and comments. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 373–375.

- Dana, Charles A. (1898). Recollections of the Civil War: with the leaders at Washington and in the field in the sixties. New York: D. Appleton and Company. pp. 105–106.

- "A Powerful Defense and Vindication of Andrew Johnson". The Bristol Evening News. September 11, 1908. p. 5. Retrieved 2023-08-02. & "Brownlow (2 of 2)" Newspapers.com, The Bristol Evening News, September 11, 1908, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-bristol-evening-news-brownlow-2-of/129329833/

- Crook, W. H.; Gerry, Margarita Spalding (1910). Through five administrations. New York and London: Harper & brothers. p. 83.

- Depew, Chauncey M. (1924). My memories of eighty years. New York: C. Scribner's sons. pp. 49–50 – via HathiTrust.

- "A Trump Card—Now Andy Johnson 'Makes His Jack'". The Daily Register. November 22, 1862. p. 4. Retrieved 2023-07-09 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The President's Speech". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. February 23, 1866. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- Butler, Benjamin F.; Miscellaneous Pamphlet Collection (Library of Congress) (1866). Lecture delivered at the Brooklyn academy of music. pp. 11–12.

- "Delaware Gazette and State Journal 31 Aug 1866, page 2". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- "Tears". White Cloud Kansas Chief. August 30, 1866. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- Berkelman, Robert. "Thomas Nast, Crusader and Satirist." New Mexico Quarterly 27, 3 (1957). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ nmq/vol27/iss3/3

- Wise, John S. (1906). Recollections of thirteen presidents. New York: Doubleday, Page & Co. pp. 111–112 – via HathiTrust.