Sam Johnson (Tennessee)

Sam Johnson (c. 1830–after 1901) was a laborer and carpenter who was enslaved by Andrew Johnson from 1842 until 1863. Sam Johnson was also a musician ("He played a violin he made himself that could be heard for a mile around...") and built his own home.[1] In 1928, Andrew Johnson biographer Robert W. Winston described Sam as "Johnson's favorite slave."[2]

.jpg.webp)

Biography

Andrew Johnson paid a man named Elim Carter US$541 (equivalent to $16,405 in 2022) for Sam in 1842. Two months later he paid $500 for Sam's older half-sister Dolly. Both were enslaved by Johnson until 1863, when he emancipated them amidst the ongoing American Civil War.[1] In the 1840s, Andrew Johnson regularly hired out Sam around town for jobs including "plastering a house, pulling corn, cutting oats with scythe and cradle, and doing janitorial work by 'attending the Court House.'" The income from this work was typically paid to Andrew Johnson.[1] In January 1860, Charles Johnson wrote Andrew Johnson telling him he ought to sell Sam because he had refused to do some wood-cutting work Eliza had requested and wanted to be paid the full amount of his wages rather than a fraction.[3] During the Civil War, after Andrew Johnson fled Tennessee on June 12, 1861, Sam worked for a Greeneville farmer named Robert C. Carter likely in "an attempt to avoid Confederate confiscation of Andrew Johnson's property, including his slaves."[3]

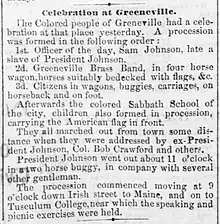

After the conclusion of the American Civil War, Samuel Johnson became a commissioner for the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands.[4] Johnson is credited with organizing the first Freedom Day celebration in Tennessee, a celebration of the anniversary of the day Andrew Johnson freed Sam and his other personal slaves, on August 8, 1863. August 8 is still celebrated as Emancipation Day in Tennessee and parts of Kentucky, Missouri, and Virginia.[5][6] Emancipation Day "celebrations remained relatively small and isolated to small towns in upper East Tennessee throughout the 1870s. During the 1880s, the celebration spread across the region and the state, connecting Andrew Johnson to the memory of emancipation in Tennessee."[7]

According to the Knoxville Mercury Project, over the decades Tennessee Emancipation Day developed into quite an event:[8]

For years, Knoxville blacks boarded trains for the annual festivities in Greeneville. By the early 1900s, it was a major holiday in Knoxville, often an occasion for baseball and softball games, dances, and boxing matches, most often at Chilhowee Park. At least once, Emancipation Day witnessed an all-black automobile race. Held in 1929 at the Knoxville Motor Speedway, the race was won by Grant Haynes, driving a Chevrolet Special. Emancipation Day was sometimes an occasion for a downtown parade, often involving local black physician Dr. J.H. Presnell, known as Knoxville’s “Bronze Mayor.” Once, in 1931, a Knoxville judge freed 13 blacks arrested for dancing and singing in the streets late at night, citing the upcoming Emancipation Day holiday. By the 1930s, Emancipation Day was the occasion for a big dance, sometimes featuring major performers. Louis Armstrong was there in 1937, just for Emancipation Day at Chilhowee Park. In years to come, the holiday would bring Tiny Bradshaw (1939), Amos Milburn (1950), Buddy Johnson (1951), Lloyd Price (1952), and Lionel Hampton (1953).

Sam Johnson's great-great-grandson Ned Arter was a featured guest at Tennessee Emancipation Day celebrations in 2012 and 2023.[9]

He supported his family by working as a carpenter,[3] and lived on land in Greeneville known as Johnson's Woods.[10] Circa 1901, he had white hair, owned his house and was considered an important figure in the African-American community of East Tennessee.[11]

Family

Sam married a woman named Margaret in the mid-1850s. They ultimately had nine children together, eight daughters and a son.[1]

- Dora

- Robert

- Hattie

References

- "Slaves of Andrew Johnson". Andrew Johnson National Historic Site. U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- Winston, Robert W. (1928). Andrew Johnson, Plebeian and Patriot. New York: H. Holt and company. p. 103 – via HathiTrust.

- Schroeder-Lein, Glenna R.; Zuczek, Richard (2001-06-22). Andrew Johnson: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO. p. 269. ISBN 978-1-57607-030-7.

- "The Formerly Enslaved Households of President Andrew Johnson". WHHA (en-US). Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- "Emancipation Day in Tennessee and Its Ties to the Beginnings of Black Philanthropy". Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee - Nashville, TN. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- "The History of Emancipation Day in Tennessee". tnmuseum.org. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- Miller, Zachary A. (August 2022). False Idol: The Memory of Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction in Greeneville, Tennessee 1869-2022 (Master of Arts thesis). Eastern Tennessee State University. p. 38. Paper 4096.

- Project, Knoxville History (2016-08-12). "Emancipation Week: the Backstory of the Eighth of August". The Knoxville Mercury. Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- "The Libation". www.beckcenter.net. Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- "Mary J Stover in the Tennessee, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1779-2008", Wills, V. 1-2, 1838-1915, Tennessee County Court (Sullivan County); Probate Place: Sullivan, Tennessee, Page images 226–231 of 774 – via Ancestry.com,

...being in Greene Co. Tennessee known as the Johnson woodland tract a portion of which was sold to Samuel Johnson [?] by the heirs of my father and being apart of the same land on which he now lives...

- "Emancipation Day at Greeneville". Morristown Republican. 1901-08-17. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-08-01.