American gentry

The American gentry were rich landowning members of the American upper class in the colonial South.

The Colonial American use of gentry was not common. Historians use it to refer to rich landowners in the South before 1776. Typically, large scale landowners rented out farms to white tenant farmers. North of Maryland, there were few large comparable rural estates, except in the Dutch domains in the Hudson Valley of New York.[1][2]

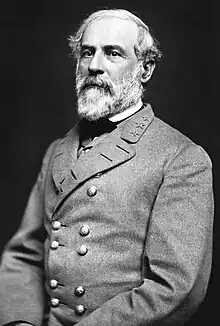

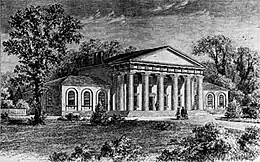

The families of Virginia (see First Families of Virginia) who formed the Virginia gentry class, such as General Robert E. Lee's ancestors, were among the earliest settlers in Virginia. Lee's family of Stratford Hall was among the oldest of the Virginia gentry class. Lee's family is one of Virginia's first families, originally arriving in the Colony of Virginia from the Kingdom of England in the early 17th century. The family's founder was Richard Lee I, Esquire, "the Immigrant" (1618–1664), from the county of Shropshire. Robert E. Lee's mother grew up at Shirley Plantation, one of the most elegant homes in Virginia. His maternal great-great grandfather, Robert "King" Carter of Corotoman, was the wealthiest man in the colonies when he died in 1732.[3]

Thomas Jefferson, the patron of American agrarianism, wrote in his Notes on Virginia (1785), "Those who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God, if He ever had a chosen people, whose breasts He has made His peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue." Jefferson who spent much of his childhood at Tuckahoe Plantation was a great-grandson of William Randolph, a colonist and land owner who arrived in Virginia from England in the mid-17th century. Randolph played an important role in the history and government of the English colony of Virginia.

George Washington was a commercial farmer interested in innovations, and quit his public duties in 1783 and again in 1797 to manage his plantation at Mount Vernon. Washington lived an upper-class lifestyle. Like most planters in Virginia, Washington imported luxury items and other fine wares from England. He paid for them by exporting his tobacco crop.

Extravagant spending and the unpredictability of the tobacco market meant that many Virginia planters' financial resources were unstable. Thomas Jefferson was deeply in debt when he died, and his heirs were forced to sell Monticello to cover his debts. In 1809, Henry Lee III, Robert E. Lee's father, went bankrupt and served one year in debtors' prison in Montross, Virginia; Robert was two years old at the time.[4][5] Despondent and nearly broke, William Byrd III of Westover Plantation committed suicide in 1777.

Wood notes that "Few members of the American gentry were able to live idly off the rents of tenants as the English landed aristocracy did."[6] Some landowners, especially in the Dutch areas of Upstate New York, leased out their lands to tenants, but generally—"Plain Folk of the Old South"—ordinary farmers owned their cultivated holdings.[7]

The First Families of Virginia and the colonial families of Maryland

.jpg.webp)

The First Families of Virginia originated with colonists from England who primarily settled at Jamestown and along the James River and other navigable waters in the Colony of Virginia during the 17th century. As there was a propensity to marry within their narrow social scope for many generations, many descendants bear surnames which became common in the growing colony.

Many of the original English colonists considered members of the First Families of Virginia emigrated to the Colony of Virginia during the English Civil War and English Interregnum period (1642–1660). Royalists left England on the accession to power of Oliver Cromwell and his Parliament. Because most of Virginia's leading families recognized Charles II as King following the execution of Charles I in 1649, Charles II is reputed to have called Virginia his "Old Dominion", a nickname that endures today. The affinity of many early aristocratic Virginia settlers for the Crown led to the term "distressed Cavaliers", often applied to the Virginia oligarchy. Many Cavaliers who served under King Charles I fled to Virginia. Thus, it came to be that the First Families of Virginia often refer to Virginia as "Cavalier Country". These men were offered rewards of land, etc., by King Charles II, but they had settled Virginia and so remained in Virginia.

Most of such early settlers in Virginia were so-called "Second Sons". Primogeniture favored first sons' inheriting lands and titles in England. Virginia evolved in a society of second or third sons of Englishmen who inherited land grants or land in Virginia. They formed part of the Southern elite in Colonial America.

Many of the great Virginia dynasties traced their roots to families like the Lees and the Fitzhughs, who traced their lineage to England's county families and baronial legacies. Some, however, came from much more humble origins; such families as the Shackelfords, who gave their name to a Virginia hamlet, rose from modest beginnings in England to a place in the Virginia firmament. Some families, like the Gilliams, arrived in Virginia in the 17th century as indentured servants; by the late 18th century they had amassed several large plantations, including Weston Manor, and became landed gentry in the colony. Families such as the Mathews from later Scotch-Irish immigration also formed political dynasties in Old Virginia. At the same time, other once-great families were decimated not only by the English Civil War, but also by the enormous power of the London merchants to whom they were in debt and who could move markets "with the stroke of a pen."

The colonial families of Maryland were the leading families in the Province of Maryland. Several also had interests in the Colony of Virginia, and the two are sometimes referred to as the Chesapeake Colonies. Many of the early settlers came from the West Midlands in England, although the Maryland families were composed of a variety of European nationalities, e.g. French, Irish, Welsh, Scottish, and Swedish, in addition to English.

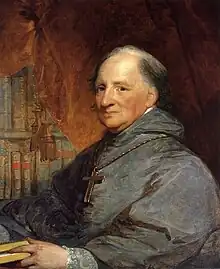

The Carroll family is an example of a prominent political family from Maryland, of Irish descent and origin in the ancient kingdom of Éile, commonly anglicized Ely, as a branch of the ruling O'Carroll family. Another is the Mason family of Virginia, who descended from the progenitor of the Mason family, George Mason I, a Cavalier member of the Parliament of England born in Worcestershire, England. The Riggin family of Maryland who also had holdings on the Eastern Shore of Virginia is of Irish descent and origin in the Kingdom of Munster. The Elisha Riggin House, built by Crisfield shipbuilder Elisha Riggin is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Charles I of England granted the province palatinate status under Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore. The foundational charter created a quasi-aristocracy (the lords of the manor) for Maryland. Maryland was uniquely created as a colony for Catholic settlers to find a haven from religious persecution, but Anglicanism eventually came to dominate, partly through influence from neighboring Virginia.

References

- See François-Joseph Ruggiu, "Extraction, wealth and industry: The ideas of noblesse and of gentility in the English and French Atlantics (17th–18th centuries)." History of European Ideas 34.4 (2008): 444-455 online

- Arthur M. Schlesinger, “The Aristocracy in Colonial America.” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. 74, 1962, pp. 3–21. online

- Douglas Southall Freeman, R. E. Lee: A Biography (1934) online ch 1

- A Princeton Companion (Lee, Henry), 1978, archived from the original on June 2, 2010, retrieved August 20, 2010

- Stratford Hall/Lee Family Tree: Henry Lee III, archived from the original on June 2, 2010, retrieved August 20, 2010

- Gordon S. Wood (2011). The Radicalism of the American Revolution. Knopf Doubleday. p. 113. ISBN 9780307758965.

- Charles C. Bolton, "Planters, Plain Folk, and Poor Whites in the Old South." in Lacy K. Ford, ed., A Companion to the Civil War and Reconstruction, (2005) pp 75-93.

Further reading

- Ruggiu, François-Joseph. "Extraction, wealth and industry: The ideas of noblesse and of gentility in the English and French Atlantics (17th–18th centuries)." History of European Ideas 34.4 (2008): 444-455 online

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. “The Aristocracy in Colonial America.” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. 74, 1962, pp. 3–21. online