Alexander the Great in legend

There are many legendary accounts surrounding the life of the Macedonian king Alexander the Great, with a relatively large number deriving from his own lifetime, probably encouraged by Alexander himself.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Early rule

Conquest of the Persian Empire

Expedition into India

Death and legacy

Cultural impact

|

||

Ancient

Prophesied conqueror

King Philip had a dream in which he took a wax seal and sealed up the womb of his wife. The seal bore the image of a lion. The seer Aristander interpreted this to mean that Olympias was pregnant, since men do not seal up what is empty, and that she would bring forth a son who would be bold and lion-like.[1] (Ephorus FGrH 70 217)

After Philip took Potidaea in 356 BC, he received word that his horse had just won at the Olympic games, and that Parmenion had defeated the Illyrians. Then he got word of the birth of Alexander. The seers told him that a son whose birth coincided with three victories would always be victorious.[2] When the young Alexander tamed the steed Bucephalus, his father noted that Macedonia would not be large enough for him.[2]

Deified Alexander

In 336 BC, Philip sent Parmenion with an army of 10,000 men, as vanguard of a force to free the Greeks living on the western coast of Anatolia from Persian rule. The people of Eresus on the island Lesbos erected an altar to Zeus Philippios. Alexander himself was the model for the image of Apollo on coins issued by his father.[3]

When Alexander went to Egypt, he was given the title "pharaoh," which included the epithet "Son of Ra," the Egyptian personification of the sun. A story told that one night King Philip had found a huge snake in the bed next to his sleeping wife. Olympias was from Epirus and may have practiced a mystery cult that involved snake-handling.[2] The snake was said to be Zeus Ammon in disguise. After his visit to the Siwa Oasis in February 331 BC, Alexander often referred to Zeus-Ammon as his true father. Upon his return to Memphis in April, he met envoys from Greece who reported that the Erythraean Sibyl had confirmed that Alexander was the son of Zeus.[3]

By 330 BC, Alexander had started to adopt elements of Persian royal dress.[3] In 327 BC he introduced proskynesis, a ritualized honor accorded by Persians to their rulers. The Greek soldiers resisted, as such prostrations were reserved for honoring the gods. They considered this blasphemy on Alexander's part and sure to bring condemnation from the gods.[4]

- When the Pythia refused to answer Alexander, he began to drag her to the temple. Whereupon Pythia exclaimed, You are invincible o young! (aniketos ei o pai!) (Plutarch Al. 14. 6-7)

- The one who could manage to untie the Gordian knot would become the king of Asia. (Arrian 2.3)

- Although Daniel does not refer to him by name, Alexander is the he-goat and King of Javan (Greece), coming from the west and crossing the earth without touching the ground. He charges the ram in great rage. He shatters the horns of Media and Persia and knocks the ram to the ground and tramples it. (Daniel 8:3-8).[5]

- Alexander was born on the same day the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus was burnt down. Plutarch remarked that Artemis was too preoccupied with Alexander's delivery to save her burning temple. Alexander later offered to pay for the temple's rebuilding, but the Ephesians refused on the ground that it was inappropriate for a god to dedicate offerings to other gods. (Strabo 14.1.22)

- Apelles painted Alexander holding a thunderbolt of Zeus.

- Decree of the Ionian League (uncertain date): … so that we should [pass the day on which King Antiochus] was born in … reverence [ … To each person participating in the festival] shall be given [a sum] equivalent to that given for [the sacrifice and procession for Alexander][6]

Offering of a Scythian donkey's horn at Delphi

Claudius Aelianus in the "Characteristics of Animals" write that they say that in Scythia there were horned donkeys, and their horns were holding water from the river Styx. Adding that Sopater brought one of these horns to Alexander, then Alexander set up the horn as a votive offering at Delphi, with an inscription beneath it.[7]

Jewish legends

Josephus in his Antiquities of the Jews mentions that Alexander visited Jerusalem and saluted the high priest, saying that he had seen him in his dreams back in Macedonia.[8]

The Talmud also has many legends relating to Alexander, For example, it mentions that the Samaritans conspired for the destruction of the temple, but Alexander prostrated himself at the feet of the high priest Simon the Just. It also mentions many other legends on Alexander, such as: The Ten Questions of Alexander to the Sages of the South, his Journey to the Regions of Darkness, the Amazons, the Gold Bread, Alexander at the Gate of Paradise, his ascent into the air, and Descent into the Sea.[9][10]

According to the Talmud, Alexander reached the gates of Paradise:

In the course of his adventures in the mythical East, Alexander reached the entrance of the Garden of Eden and raised a loud voice, calling out: “Open the gate for me!” The sentry of the Garden of Eden said to him: “This is the gate of the Lord; the righteous shall enter into it. Since you are not righteous, you may not enter.” He said to them: "If I will not be admitted, at least give me something from inside." They gave him one eyeball. He brought it and he weighed all the gold and silver that he had against the eyeball, and yet the riches did not balance against the eyeball’s greater weight. He said to his philosophers: "What is this? Why does this eyeball outweigh everything?" They said: "It is the eyeball of a mortal person of flesh and blood, which is not satisfied ever." He said to them: "From where do you know that this is the reason for the unbalanced scale?" The philosophers answered him: "Take a small amount of dirt and cover the eye." He did so, and it was immediately balanced by its proper counterweight. The eye is never satisfied while it can see. – Tractate Tamid 32b

There is also the legend of the Egyptians suing the Jews before Alexander.[11]

Alexander Romance

In the first centuries after Alexander's death, probably in Alexandria, a quantity of the more legendary material coalesced into a text known as the Alexander Romance, later falsely ascribed to the historian Callisthenes and therefore known as Pseudo-Callisthenes. This text underwent numerous expansions and revisions throughout Antiquity and the Middle Ages, exhibiting a plasticity unseen in "higher" literary forms. Latin and Syriac translations were made in Late Antiquity. From these, versions were developed in all the major languages of Europe and the Middle East, including Middle Persian, Syriac, Armenian, Georgian, Persian, Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew, Serbian, Slavonic, Romanian, Hungarian, Spanish, German, Scots, English, Italian, and French.

Oriental tradition

- The Gates of Alexander (Caspian Gates) were a legendary barrier supposedly built by Alexander in the Caucasus to keep the uncivilized barbarians of the north (typically associated with Gog and Magog) from invading the land to the south.

- Alexander is often identified with Dhu al-Qarnayn, literally "The Two-Horned One", mentioned in the Quran, Al-Kahf 18:83–94. Similarities between the Quranic account and the Syriac Alexander Legend were also found in recent research[12] (see Alexander in the Qur'an).[13] The Arabic tradition also elaborated the legend that Alexander the Great had been the companion of Aristotle and Plato.

- Persian accounts of the Alexander legend, known as the Iskandarnamah, combined the Pseudo-Callisthenes and Syriac material about Alexander, some of which is found in the Qur'an, with Sasanian Persian ideas about Alexander the Great. This is an ironic outcome considering Zoroastrian Persia's hostility to the national enemy who finished the Achaemenid Empire, but was also directly responsible for centuries of Persian domination by Hellenistic "foreign rulers".[15] However, he is sometimes not depicted as a warrior and conqueror, but as a seeker of truth who eventually finds the Ab-i Hayat (Water of Life).[16] Persian sources on the Alexander legend devised a mythical genealogy for him whereby his mother was a concubine of Darius II, making him the half-brother of the last Achaemenid king, Darius III. By the 12th century such important writers as Nezami Ganjavi were making him the subject of their epic poems. The Romance and the Syriac Legend are also the sources of incidents in Ferdowsi's "Shahnama".[17] In the Shahnameh, the Persian epic, Kai Bahman's elder son Dara(b) is killed in battle with Alexander the Great, that is, Dara/Darab is identified as Darius III and which then makes Bahman a figure of the 4th century BC. In another tradition, Alexander is the son of Dara/Darab and his wife Nahid, who is described to be the daughter of "Filfus of Rûm" i.e. "Philip the Greek" (cf. Philip II of Macedon)[18][19]

- A Mongolian version is also extant.

- The Malay language Hikayat Iskandar Zulkarnain was written about Alexander the Great as Dhul-Qarnayn and the ancestry of several Southeast Asian royal families is traced from Iskandar Zulkarnain, through Raja Rajendra Chola (Raja Suran, Raja Chola) in the Malay Annals, such as the Sumatra Minangkabau royalty.[20][21]

- Alexander the Great was claimed as the ancestor of the Hunza rulers.[22]

Western tradition

Epic poems based on Alexander romance

- Alexandreis Latin

- Alexanderlied German

- Li romans d'Alixandre French

- Libro de Alexandre Spanish

- Alexanders saga Old Norse-Icelandic

- The Buik of Alexander Scottish

- Aethicus Ister (Latin) has numerous passages which deal directly with the legends of Alexander

- Azo a legendary ruler of Georgians, who had been installed by Alexander.

Women and Alexander

- According to Greek Alexander Romance, Queen Thalestris of the Amazons brought 300 women to Alexander the Great, hoping to breed a race of children as strong and intelligent as he.

- According to Greek Alexander Romance, Alexander encountered the Nubian Queen Candace of Meroë

- A popular Greek legend[23][24] talks about a mermaid who lived in the Aegean for hundreds of years who was thought to be Alexander's sister Thessalonike. The legend states that Alexander, in his quest for the Fountain of Immortality, retrieved with great exertion a flask of immortal water with which he bathed his sister's hair. When Alexander died his grief-stricken sister attempted to end her life by jumping into the sea. Instead of drowning, however, she became a mermaid passing judgment on mariners throughout the centuries and across the seven seas. To the sailors who encountered her she would always pose the same question: "Is Alexander the king alive?" (Greek: Zei o vasilias Alexandros?), to which the correct answer would be "He lives, still rules, and conquers the World" (Greek: Zei kai vasilevei kai ton kosmon kyrievei!). Given this answer she would allow the ship and her crew to sail safely away in calm seas. Any other answer would transform her into the raging Gorgon, bent on sending the ship and every sailor on board to the bottom.[25][26]

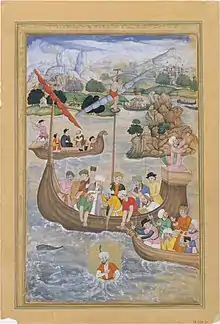

Alexander sees the whole world

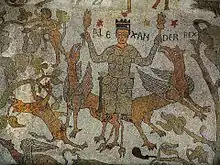

A medieval legend in the Alexander romance had Alexander, wishing to see the whole world, first descending into the depths of the ocean in a sort of diving bell, then wanting to see the view from above. To do this he harnessed two large birds, or griffins in other versions, with a seat for him between them. To entice them to keep flying higher he placed meat on two skewers which he held above their heads.

Around 1260, Bertold von Regensburg preached, that like Alexander believed that "he could take down the highest stars from the sky by hand, so you too would like to go up in the air if you could". But the story showed where such a climb would lead, and proved that the great Alexander "was one of the greatest fools the world has ever seen".[27]

The scene was quite commonly depicted in medieval cultures, from Europe to Persia, where it may reflect earlier legends or iconographies. Sometimes the beasts are not shown, just the king holding two sticks with flower-like blobs at their ends. The scene is shown in the famous 12th-century floor mosaic in Otranto Cathedral, with a titulus of "ALEXANDER REX"; it also appears on the floor of Trani Cathedral.

In a paper published in 2014, Sir John Boardman endorsed the earlier suggestion by David Talbot Rice that the figure on the Anglo-Saxon Alfred Jewel was intended to represent this scene, which refers to knowledge coming through sight, and so would be appropriate for an aestel, or pointer for reading, such as the jewel. Boardman detects the same meaning in the figure representing sight on the Anglo-Saxon Fuller Brooch.[28]

Apocryphal letters

- Leon of Pella wrote the book On the Gods in Egypt, based on an apocryphal letter of Alexander to his mother Olympias.

- Epistola Alexandri ad Aristotelem concerning the marvels of India.

References

- Plutarch Al. 2.2–3

- Worthington, I. (2014). Alexander the Great: Man and God. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-86644-2. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- "Lendering, Jona. "Alexander the God", Livius.org". Archived from the original on 2016-12-01. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- Hamblin, William and Peterson, Daniel. "Alexander the Great wasn't content to be merely human", Deseret News, August 23, 2014

- Willmington's Guide to the Bible By H. L. Willmington Page 821 ISBN 978-0-8254-1874-7

- The Hellenistic world from Alexander to the Roman conquest By M. M. Austin Page 242 ISBN 0-521-29666-8

- Aelian, Characteristics of Animals, § 10.40

- Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XI

- Jewish Encyclopedia, Alexander The Great

- "Chabad, Alexander in Jerusalem". Archived from the original on 2014-11-08. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- "Chabad, Egyptians Sue the Jews". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- Darvishi, Dariush, The Alexander Romance, page 44-51, Tehran, Negah-e Moaser, 2022]

- Fastina Doufikar-Aerts (2016). "Coptic Miniature Painting in the Arabic Alexander Romance". Alexander the Great in the Middle Ages: Transcultural Perspectives. University of Toronto Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-4426-4466-3.

The essence of his theory is that parallels can be found in the Quranic verses on Dhu'l-qarnayn (18:82-9) and the Christian Syriac Alexander Legend. The hypothesis requires a revision, because Noldeke's dating of Jacob of Sarug's Homily and the Christian Syriac Alexander Legend is no longer valid; therefore, it does not need to be rejected, but it has to be viewed from another perspective. See my exposé in Alexander Magnus Arabicus (see note 7), chapter 3.3 and note 57.

- ""Alexander is Lowered into the Sea", Folio from a Khamsa (Quintet) of Amir Khusrau Dihlavi, 1597–98". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2018-12-14.

- E.g. the Greek scholar G. G. Aperghis goes so far as to state: "Rather than considering the arrival of the Greeks as bringing something entirely new to the management of an empire, one should probably see them as apt pupils of excellent [Achaemenian] teachers. (link)"

- Algar, Hamid (1973). Mīrzā Malkum Khān: A Study in the History of Iranian Modernism. University of California Press. p. 292, ft. 26. ISBN 9780520022171.

- Manteghi, Haila (2018-02-28). Alexander the Great in the Persian Tradition: History, Myth and Legend in Medieval Iran. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78672-366-6.

The Shahnama also contains parts from the Syriac sources discussed in the first chapter of this book: the Syriac Alexander Romance (such as the dragon slaying and the journey to Chin), episodes from the Syriac Legend and Poem (such as Gog and Magog, and the Water of Life) and the philosophers' laments over Alexander's tomb.

- Encyclopædia Iranica - Page 12 ISBN 978-0-7100-9109-3

- Alexander the Great was called "the Ruman" in Zoroastrian tradition because he came from Greek provinces which later were a part of the eastern Roman empire - The archeology of world religions By Jack Finegan Page 80 ISBN 0-415-22155-2

- John N. Miksic (30 September 2013). Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300_1800. NUS Press. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-9971-69-574-3.

- Marie-Sybille de Vienne (9 March 2015). Brunei: From the Age of Commerce to the 21st Century. NUS Press. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-9971-69-818-8.

- Edward Frederick Knight (1893). Where Three Empires Meet: A Narrative of Recent Travel in Kashmir, Western Tibet, Gilgit, and the Adjoining Countries. Longmans, Green, and Company. p. 330.

- Mermaids and Ikons: A Greek Summer (1978) page 73 by Gwendolyn MacEwen ISBN 978-0-88784-062-3

- Folktales from Greece Page 96 ISBN 1-56308-908-4

- Angelopoulos, Anna. "Greek Legends about Fairies and Related Tales of Magic". In: Fabula Vol. 51, Ed. 3/4, (2010): 218 (type b), 220. DOI:10.1515/FABL.2010.021

- Dawkins, R. M. “ALEXANDER AND THE WATER OF LIFE.” Medium Ævum 6, no. 3 (1937): 183-185, 189. https://doi.org/10.2307/43626046.

- Bernd und Hiltrud Hainmüller (n.d.). "Weltbilder des Mittelalters,Station 4: Innenraum – Symbolik in visuellen Medien,1. Die romanischen Skulpturen". hainmueller.de. Retrieved 2022-03-16.

- Boardman, John, "Alfred and Alexander", pp. 137-139, in: Gosden, Christopher, Crawford, Sally, Ulmschneider, Katharina, Celtic Art in Europe: Making Connections, 2014, Oxbow Books, ISBN 1782976582, 9781782976585, google books

Further reading

- Stoneman, Richard (ed.). Alexander the Great: the Making of a Myth. London: British Library, 2022. Accompanied the exhibition of the same name. ISBN 9780712354479 (pbk); ISBN 9780712354769 (hbk).

- Stoneman, Richard. Alexander the Great: a Life in Legend. New Haven, Conn.; London: Yale University Press, 2008. ISBN 9780300112030 (hbk).