Zealandia

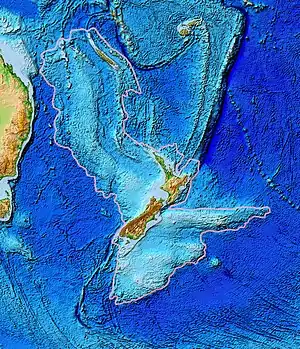

Zealandia (pronounced /ziːˈlændiə/), also known as Te Riu-a-Māui (Māori)[2] or Tasmantis,[3][4] is an almost entirely submerged mass of continental crust in Oceania that subsided after breaking away from Gondwana 83–79 million years ago.[5] It has been described variously as a submerged continent, continental fragment, and microcontinent.[6] The name and concept for Zealandia was proposed by Bruce Luyendyk in 1995,[7] and satellite imagery shows it to be almost the size of Australia.[8] A 2021 study suggests Zealandia is 1 billion years old, about twice as old as geologists previously thought.[9]

By approximately 23 million years ago, the landmass may have been completely submerged.[10][11] Today, most of the landmass (94%) remains submerged beneath the Pacific Ocean.[12] New Zealand is the largest part of Zealandia that is above sea level, followed by New Caledonia.

Mapping of Zealandia concluded in 2023.[13] With a total area of approximately 4,900,000 km2 (1,900,000 sq mi),[6] Zealandia is substantially larger than any features termed microcontinents and continental fragments. If classified as a microcontinent, Zealandia would be the world's largest microcontinent. Its area is six times the area of Madagascar, the next-largest microcontinent in the world,[6] and more than half the area of the Australian continent. Zealandia is more than twice the size of the largest intraoceanic large igneous province (LIP) in the world, the Ontong Java Plateau (approximately 1,900,000 km2 or 730,000 sq mi), and the world's largest island, Greenland (2,166,086 km2 or 836,330 sq mi). Zealandia is also substantially larger than the Arabian Peninsula (3,237,500 km2 or 1,250,000 sq mi), the world's largest peninsula, and the Indian subcontinent (4,300,000 km2 or 1,700,000 sq mi). Due to these and other geological considerations, such as crustal thickness and density,[14][15] some geologists from New Zealand, New Caledonia, and Australia have concluded that Zealandia fulfills all the requirements to be considered a continent rather than a microcontinent or continental fragment.[6] Geologist Nick Mortimer commented that if it were not for the ocean level, it would have been recognized as such long ago.[16]

Zealandia supports substantial inshore fisheries and contains gas fields, of which the largest known is the New Zealand Maui gas field, near Taranaki. Permits for oil exploration in the Great South Basin were issued in 2007.[17] Offshore mineral resources include ironsands, volcanic massive sulfides and ferromanganese nodule deposits.[18]

Etymology

GNS Science recognizes two names for the landmass. In English, the most common name is Zealandia, a latinate name for New Zealand; the name was coined in the mid-1990s and became established through common use. In the Māori language, the landmass is named Te Riu-a-Māui, meaning 'the hills, valleys, and plains of Māui'.[2]

Geology

The Zealandia continent is largely made up of two nearly parallel ridges, separated by a failed rift, where the rift breakup of the continent stops and becomes a filled graben. The ridges rise above the sea floor to heights of 1,000–1,500 m (3,300–4,900 ft), with a few rocky islands rising above sea level. The ridges are continental rock, but are lower in elevation than normal continents because their crust is thinner than usual, approximately 20 km (12 mi) thick, and consequently, they do not float so high above Earth's mantle as that of most landmasses.

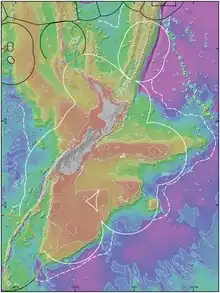

About 25 million years ago, the southern part of Zealandia (on the Pacific Plate) began to shift relative to the northern part (on the Indo-Australian Plate). The resulting displacement by approximately 500 km (310 mi) along the Alpine Fault is evident in geological maps.[19] Movement along this plate boundary also has offset the New Caledonia Basin from its previous continuation through the Bounty Trough.

Compression across the boundary has uplifted the Southern Alps, although due to rapid erosion their height reflects only a small fraction of the uplift. Farther north, subduction of the Pacific Plate has led to extensive volcanism, including the Coromandel and Taupo Volcanic Zones. Associated rifting and subsidence has produced the Hauraki Rift and more recently, the Whakatane Graben and Wanganui Basin.

Volcanism

Volcanism on Zealandia has taken place repeatedly in various parts of the continental fragment before, during, and after it rifted away from the supercontinent Gondwana. Although Zealandia has shifted approximately 6,000 km (3,700 mi) to the northwest with respect to the underlying mantle from the time when it rifted from Antarctica, recurring intracontinental volcanism exhibits magma composition similar to that of volcanoes in previously adjacent parts of Antarctica and Australia. Large volume magmatism occurred in two periods, being in the Devonian (370 to 368 million years ago) and the Early Cretaceous (129 to 105 million years ago).[20]

This volcanism is widespread across Zealandia, but on present land generally it is of low volume apart from the huge mid to late Miocene shield volcanoes that developed the Banks and Otago Peninsulas. In addition, it took place continually in numerous limited regions all through the Late Cretaceous and the Cenozoic. Some of its causes remain in dispute perhaps because of data gaps.[20] During the Miocene, the northern section of Zealandia (Lord Howe Rise) might have slid over a stationary hotspot, forming the Lord Howe Seamount Chain.[21]

It has been suggested that Zealandia may have played an important part in the origin of the Pacific Ocean's volcanic Ring of Fire.[22]

Geological subdivisions

Occasionally, Zealandia is divided into two regions by scientists: North Zealandia (or Western Province); and South Zealandia (or Eastern Province), the latter of which contains most of the Median Batholith crust. These two features are separated by the Alpine Fault and Kermadec Trench and by the wedge-shaped Hikurangi Plateau, and they are moving separately from each other.[14]

Classification as a continent

The case for Zealandia being a continent in its own right has been argued in the Nick Mortimer and Hamish Campbell book Zealandia: Our continent revealed (2014),[14] in which the authors presented geological and ecological evidence in support of their thesis.[23]

In 2017, a team of eleven geologists from New Zealand, New Caledonia, and Australia concluded that Zealandia fulfills all the requirements to be considered a submerged continent, rather than a microcontinent or continental fragment.[6] This verdict was widely covered in the news media.[24][25][26]

Oldest parent rocks

The younger Zealandia rocks have evidence of origins from early Gondwana formations of 500 to 700 million years ago, Rodinia formations about a billion years ago and sources from an expanded-Ur continent between 3.5 and 2 billion years ago.[27]

Tectonics

The breakup of Gondwana formed Northern Zealandia.[28] Zealandia underwent extension resulting from east to northeast-directed rollback of west to southwest-dipping subduction of the Pacific Plate.[29] which terminated between 95 million[29] to 85 million years ago.[30] After 85 million years ago Zealandia separated from Australia through seafloor spreading of the Coral and Tasman seas until this ceased 52 million years ago.[30] Shortening on an active convergent northern margin of Zealandia occurred mainly between 45 and 35 million years ago.[30] This was followed by the opening of the backarc basins of the southwest Pacific and the migration of the Tonga and Kermadec Trenchs to the east.[30] Shear extrusion followed between 23.3 million to 5 million years ago with the New Zealand Alpine Fault rupture and a southwestward extension of the Campbell Plateau relative to the Challenger Plateau.[29] Southeast Indian Ocean Ridge expansion movement completely separated Zealandia from the Antarctic at about 10 million years ago.[29] In the last 5 million years Zealandia has been generally subsiding owing to the Pacific Plate subducting westward and retreating eastward.[29]

Biogeography

New Caledonia is at the northern end of the ancient continent, while New Zealand rises at the plate boundary that bisects it. These land masses constitute two outposts of the Antarctic flora, featuring araucarias and podocarps. At Curio Bay, logs of a fossilized forest closely related to modern Kauri and Norfolk pine can be seen that grew on Zealandia approximately 180 million years ago during the Jurassic period, before it split from Gondwana.[31] The trees growing in these forests were buried by volcanic mud flows and gradually replaced by silica to produce the fossils now exposed by the sea.

As sea levels drop during glacial periods, more of Zealandia becomes a terrestrial environment rather than a marine environment. Originally, it was thought that Zealandia had no native land mammal fauna, but the discovery in 2006 of a fossil mammal jaw from the Miocene in the Otago region demonstrates otherwise.[32]

Political divisions

The total land area (including inland water bodies) of Zealandia is 286,660.25 km2 (110,680.14 sq mi). Of this, New Zealand comprises the overwhelming majority, at 267,988 km2 (103,471 sq mi, or 93.49%) that includes the mainland (North Island and South Island), nearby islands, and most outlying islands, including the Chatham Islands, the New Zealand Subantarctic Islands, the Solander Islands, and the Three Kings Islands (but not the Kermadec Islands or Macquarie Island (Australia), which are part of the rift).[33]

New Caledonia and the islands surrounding it comprise some 18,576 km2 (7,172 sq mi or 6.48%) and the remainder is made up of various territories of Australia including the Lord Howe Island Group (New South Wales) at 56 km2 (22 sq mi or 0.02%), Norfolk Island at 35 km2 (14 sq mi or 0.01%), as well as the Cato, Elizabeth, and Middleton reefs (Coral Sea Islands Territory) with 5.25 km2 (2.03 sq mi).[33][34]

Population

As of 2022, the total human population of Zealandia is approximately 5.4 million people. The largest city is Auckland with about 1.7 million people; roughly one-third of the total population of the continent.

New Zealand – 5,112,300[35]

New Zealand – 5,112,300[35] New Caledonia (France) – 268,767[36]

New Caledonia (France) – 268,767[36] Norfolk Island (Australia) – 1,748[37]

Norfolk Island (Australia) – 1,748[37] Lord Howe Island (Australia) – 382[38]

Lord Howe Island (Australia) – 382[38].svg.png.webp) Cato Reef (Australia) – 0

Cato Reef (Australia) – 0.svg.png.webp) Elizabeth Reef (Australia) – 0

Elizabeth Reef (Australia) – 0.svg.png.webp) Middleton Reef (Australia) – 0

Middleton Reef (Australia) – 0

See also

References

- "Figure 8.1: New Zealand in relation to the Indo-Australian and Pacific Plates". The State of New Zealand's Environment 1997. 1997. Archived from the original on 18 January 2005. Retrieved 20 April 2007.

- "The origin and meaning of the name Te Riu-a-Māui/Zealandia". www.gns.cri.nz. GNS Science. 2 May 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- Flannery, Tim (2002). The Future Eaters: An Ecological History of the Australasian Lands and People. Grove Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8021-3943-6. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- Danver, Steven L. (22 December 2010). Popular Controversies in World History: Investigating History's Intriguing Questions. ABC-CLIO. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-59884-078-0. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016.

Zealandia or Tasmantis, with its 3.5 million square km territory being larger than Greenland, ...

- Gurnis, M., Hall, C.E., and Lavier, L.L., 2004, Evolving force balance during incipient subduction: Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, v. 5, Q07001, https://doi.org/10.01029/02003GC000681

- Mortimer, Nick; Campbell, Hamish J. (2017). "Zealandia: Earth's Hidden Continent". GSA Today. 27: 27–35. doi:10.1130/GSATG321A.1. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017.

- Luyendyk, Bruce P. (April 1995). "Hypothesis for Cretaceous rifting of east Gondwana caused by subducted slab capture". Geology. 23 (4): 373–376. Bibcode:1995Geo....23..373L. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1995)023<0373:HFCROE>2.3.CO;2.

- Gorvett, Zaria (8 February 2021). "The missing continent it took 375 years to find". BBC. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- Aylin Woodward (14 August 2021). "A fragment of a mysterious 8th continent is hiding under New Zealand - and it's twice as old as scientists thought". Business Insider.

- "Searching for the lost continent of Zealandia". The Dominion Post. 29 September 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

We cannot categorically say that there has always been land here. The geological evidence at present is too weak, so we are logically forced to consider the possibility that the whole of Zealandia may have sunk.

- Campbell, Hamish; Gerard Hutching (2007). In Search of Ancient New Zealand. North Shore, New Zealand: Penguin Books. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-0-14-302088-2.

- Wood, Ray; Stagpoole, Vaughan; Wright, Ian; Davy, Bryan; Barnes, Phil (2003). New Zealand's Continental Shelf and UNCLOS Article 76 (PDF). Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited. Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences series 56. Wellington, New Zealand: National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. p. 16. NIWA technical report 123. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

The continuous rifted basement structure, thickness of the crust, and lack of seafloor spreading anomalies are evidence of prolongation of the New Zealand land mass to Gilbert Seamount.

- Newcomb, Tim. "Earth's Hidden Eighth Continent Is No Longer Lost". Science > Our Planet. Popular Mechanics. ISSN 0032-4558.

- Mortimer, Nick; Campbell, Hamish (2014). Zealandia: Our continent revealed. North Shore, New Zealand: Penguin Books. pp. 72 ff. ISBN 978-0-14-357156-8.

- "Zealandia: Is there an eighth continent under New Zealand?". BBC News. 17 February 2017. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- Sumner, Thomas (13 March 2017). "Is Zealandia a continent?". Science News for Students. Society for Science and the Public. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- "Great South Basin – Questions and Answers". 11 July 2007. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2008.

- "New survey published on NZ mineral deposits". 30 May 2007. Archived from the original on 16 October 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2008.

- "Figure 4. Basement rocks of New Zealand". UNCLOS Article 76: The Land mass, continental shelf, and deep ocean floor: Accretion and suturing. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 21 April 2007.

- Ringwood, M.; Schwartz, Joshua; Turnbull, Rose; Tulloch, A.J (2021). "Phanerozoic record of mantle-dominated arc magmatic surges in the Zealandia Cordillera". Geology. 49 (10): 1230–1234. Bibcode:2021Geo....49.1230R. doi:10.1130/G48916.1.

- Hansma, Jeroen; Tohver, Eric (2020). "Southward Drift of Eastern Australian Hotspots in the Paleomagnetic Reference Frame Is Consistent With Global True Polar Wander Estimates". Frontiers in Earth Science. 8: 489. Bibcode:2020FrEaS...8..489H. doi:10.3389/feart.2020.544496.

- Pappas, Stephanie (11 February 2020). "The lost continent of Zealandia hides clues to the Ring of Fire's birth". Live Science.

- Yarwood, V. (November–December 2014). "Zealandia: Our continent revealed". New Zealand Geographic. Book Review. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- Potter, Randall (16 February 2017). "Meet Zealandia: Earth's latest continent". CNN. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017.

- Hunt, Elle (16 February 2017). "Zealandia – pieces finally falling together for continent we didn't know we had". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017.

- East, Michael (16 February 2017). "Scientists discover 'Zealandia' – a hidden continent off the coast of Australia". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017.

- Adams, C; Ramsay, W (2022). "Archean and Paleoproterozoic zircons in Paleozoic sandstones in southern New Zealand: evidence for remnant Nuna supercontinent and Ur continent rocks within Zealandia". Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. 69 (8): 1061–1081. Bibcode:2022AuJES..69.1061A. doi:10.1080/08120099.2022.2091039. S2CID 251000288.

- Uruski, Christopher I. (2010). "New Zealand's deepwater frontier". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 27 (9): 2005–2026. Bibcode:2010MarPG..27.2005U. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2010.05.010. ISSN 0264-8172.

- Song, Lijun; Feng, Xuliang; Yang, Yushen; Li, Yamin (2022). "Distribution, development, transformation characteristics, and hydrate prospect prediction of the rift basins of northwest Zealandia in the Southwest Pacific". Frontiers in Earth Science. 10: 997079. Bibcode:2022FrEaS..10.7079S. doi:10.3389/feart.2022.997079. ISSN 2296-6463.

- Stratford, W.; Sutherland, R; Dickens, Gerald; Blum, Peter; Collot, Julien; Gurnis, M; Saito, S; Aurelien, Bordenave; Etienne, Samuel; Agnini, C; Alegret, L; Gayané, Asatryan; Bhattacharya, Joyeeta; Chang, Liao; Cramwinckel, Margot; Dallanave, Edoardo; Drake, Michelle; Giorgioni, Martino; Harper, Dustin; Zhou, Xiaoli (2022). "Timing of Eocene compressional plate failure during subduction initiation, northern Zealandia, southwestern Pacific". Geophysical Journal International. 229. doi:10.1093/gji/ggac016.

- "Fossil forest: Features of Curio Bay/Porpoise Bay". Archived from the original on 17 October 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- Campbell, Hamish; Gerard Hutching (2007). In Search of Ancient New Zealand. North Shore, New Zealand: Penguin Books. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-0-14-302088-2.

- "The Lost Continent of Zealandia". www.virtualoceania.net. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- Detailed map of Zealandia

- "Population | Stats NZ". www.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- "268 767 habitants en 2014". ISEE. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- "2016 Census QuickStats: Norfolk Island". quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Lord Howe Island (State Suburb)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

External links

- "Zealandia: Earth's Hidden Continent". GSA Today.

- "E Tūhura - Explore Zealandia A portal for geoscience webmaps and information on the Te Riu-a-Māui / Zealandia region". GNS NZ.

- "Zealandia: the New Zealand (drowned) Continent". Te Ara.

- Zealandia (National Geographic Encyclopedia)

- Is Zealandia a continent?

- The missing continent that took 375 years to find, By Zaria Gorvett, 7th February 2021, BBC website.

- Earth Has a Hidden 8th Continent, By Tia Ghose published February 17, 2017, livescience website.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

_political.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)