Baltica

Baltica is a paleocontinent that formed in the Paleoproterozoic and now constitutes northwestern Eurasia, or Europe north of the Trans-European Suture Zone and west of the Ural Mountains. The thick core of Baltica, the East European Craton, is more than three billion years old and formed part of the Rodinia supercontinent at c. 1 Ga.[1]

Tectonic history

._Most_researchers_place_western_(2de3cd16-15cc-4d0c-b553-71cbbeb4c7e3).jpg.webp)

Baltica formed at c. 2.0–1.7 Ga by the collision of three Archaean-Proterozoic continental blocks: Fennoscandia (including the exposed Baltic Shield), Sarmatia (Ukrainian Shield and Voronezh Massif), and Volgo-Uralia (covered by younger deposits). Sarmatia and Volgo-Uralia formed a proto-craton (sometimes called "Proto-Baltica")[2] at c. 2.0 Ga which collided with Fennoscandia c. 1.8–1.7 Ga. The sutures between these three blocks were reactivated during the Mesoproterozoic and Neoproterozoic.[3]

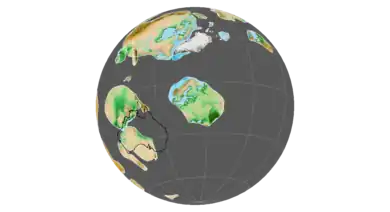

750–600 million years ago, Baltica and Laurentia rotated clockwise together and drifted away from the Equator towards the South Pole where they were affected by the Cryogenian Varanger glaciations. Initial rifting between the two continents is marked by the c. 650 Ma Egersund dike swarm in southern Norway and from 600 Ma they began to rotate up to 180° relative to each other, thus opening the Iapetus Ocean between the two landmasses. Laurentia quickly moved northward into low latitudes but Baltica remained an isolated continent in the temperate mid-latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere, closer to Gondwana, on which endemic trilobites evolved in the Early and Middle Ordovician.[4][5]

During the Ordovician, Baltica moved northward, approaching Laurentia, which again allowed trilobites and brachiopods to cross the Iapetus Ocean. In the Silurian, c. 425 Ma, the final collision between Scotland-Greenland and Norway resulted in the closure of the Iapetus and the Scandian Orogeny.[4]

Margins

Baltica is a very old continent and its core is a very well-preserved and thick craton. Its current margins, however, are the sutures that are the result of mergers with other, much younger continental blocks. These often deformed sutures do not represent the original, Precambrian–early Palaeozoic extent of Baltica; for example, the curved margin north of the Urals running parallel to Novaya Zemlya was probably deformed during the eruption of the Siberian Traps in the Late Permian and Early Triassic.[6]

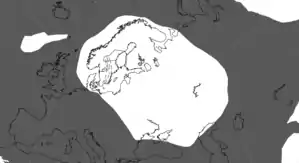

Baltica's western margin is the Caledonide orogen, which stretches northward from the Scandinavian Mountains across Barents Sea to Svalbard. Its eastern margin is the Timanide orogen which stretches north to the Novaya Zemlya archipelago.[7] The extent of the Proterozoic continent are defined by the Iapetus Suture to the west; the Trollfjorden-Komagelva Fault Zone in the north; the Variscan-Hercynian suture to the south; the Tornquist Zone to the southwest; and the Ural Mountains to the east.[8]

Northern margin

At c. 555 Ma during the Timanian Orogeny the northern margin became an active margin and Baltica expanded northward with the accretion of a series of continental blocks: the Timan-Pechora Basin, the northernmost Ural Mountains, and the Novaya Zemlya islands. This expansion coincided with the Marinoan or Varanger glaciations, also known as Snowball Earth.[9]

Terranes of the North American Cordillera, including Alaska-Chukotka, Alexander, Northern Sierra, and Eastern Klamath, share a rift history with Baltica and most likely were part of Baltica from the Caledonian orogeny until the formation of the Ural Mountains.[10] These terranes can be linked to either northeastern Laurentia, Baltica, or Siberia because of a similar sequence of fossils; detrital zircon from 2–1 Ga-old sources and evidence of Grenvillian magmatism; and magmatism and island arcs from the Late Neoproterozoic and Ordovician-Silurian.[11]

Southern margin

From at least 1.8 Ga to at least 0.8 Ga the southwestern margin of Baltica was connected to Amazonia while the southeast margin was connected to the West African Craton. Baltica, Amazonia, and West Africa rotated 75° clockwise relative to Laurentia until Baltica and Amazonia collided with Laurentia in the 1.1–0.9 Ga Grenville-Sveconorwegian-Sunsás orogenies to form the supercontinent Rodinia. When the break-up of Rodinia was complete c. 0.6 Ga Baltica became an isolated continent — a 200 million year period when Baltica was truly a separate continent.[12] Laurentia and Baltica formed a single continent until 1.265 Ga which broke up some time before 0.99 Ga. After the subsequent closure of the Mirovoi Ocean Laurentia, Baltica and Amazonia remained merged until the opening of the Iapetus Ocean in the Neoproterozoic.[13]

Western margin

The Western Gneiss Region in western Norway is composed of 1650–950 Ma-old gneisses overlain by continental and oceanic allochthons that were transferred from Laurentia to Baltica during the Scandian orogeny. The allochthons were accreted to Baltica during the closure of the Iapetus Ocean c. 430–410 Ma; Baltica's basement and the allochthons were then subducted to UHP depth c. 425–400 Ma; and they were finally exhumed to their present location c. 400–385 Ma.[14] The presence of micro-diamonds in two islands in western Norway, Otrøya and Flemsøya, indicate that this margin of Baltica was buried c. 120 km (75 mi) for at least 25 million years around 429 Ma shortly after the Baltica-Laurentia collision.[15]

The Baltica-Laurentia-Avalonia triple junction in the North Sea is the southwest corner of Baltica. The Baltica-Laurentia suture stretching northeast from the triple junction was deformed in the Late Cambrian in the Scandinavian Caledonides as well as in the Scandian Orogeny during the Silurian. Some Norwegian terranes have faunas distinct from those of either Baltica or Laurentia as a result of being island arcs that originated in the Iapetus Ocean and were later accreted to Baltica. The Baltica craton most likely underlies these terranes and the continent-ocean boundary passes several kilometres off Norway, but, since the North Atlantic opened c. 54 Ma where the Iapetus Ocean closed, it is unlikely the craton also reached into Laurentia. The margin stretches north to Novaya Zemlya where early Palaeozoic Baltica faunas have been found, but the sparsity of data makes it difficult to locate the margin in the Arctic. Ordovician faunas indicate that most of Svalbard, including Bjørnøya, was part of Laurentia, but Franz Josef Land and Kvitøya (an eastern island of the Svalbard archipelago) most likely became part of Baltica in the Timanide Orogeny. The Taymyr Peninsula, in contrast, never was part of Baltica: southern Taymyr was part of Siberia whilst northern Taymyr and the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago were part of the independent Kara Terrane in the early Palaeozoic.[16]

Eastern margin

The eastern margin, the Uralide orogen, extends 2,500 km (1,600 mi) from the Arctic Novaya Zemlya archipelago to the Aral Sea. The orogen contains the record of at least two collisions between Baltica and intra-oceanic island arcs before the final collision between Baltica and Kazakhstania-Siberia during the formation of Pangaea. The Silurian-Devonian island arcs were accreted to Baltica along the Main Uralian Fault, east of which are metamorphosed fragments of volcanic arc mixed with small amounts of Precambrian and Paleozoic continental rocks. However, no rocks unambiguously originating from either Kazakhstania or Siberia have been found in the Urals.[17] The basement of the eastern margin is composed of an Archaean craton, metamorphosed rocks at least 1.6 Ga old, which is surrounded by the fold belt of the Timanide orogeny and overlain by Mesoproterozoic sediments. The margin became a passive margin facing the Ural Ocean in the Cambrian–Ordovician.[18]

The eastern margin stretches south through the Ural Mountains from the northern end of the Novaya Zemlya archipelago. The margin follows the bent shape of Novaya Zemlya which was caused in the Late Permian by the Siberian Traps. It is clear from Baltic endemic fossils in Novaya Zemlya that the islands have been part of Baltica since the Early Palaeozoic, whereas the Taymyr Peninsula farther east was part of the passive margin of Siberia in the Early Palaeozoic. Northern Taymyr, together with Severnaya Zemlya and parts of the crust of the Arctic Ocean, formed the Kara Terrane.[19]

The Urals Mountains formed in the mid and late Palaeozoic when Laurussia collided with Kazakhstania, a series of terranes. The eastern margin, however, originally extended farther east to an active margin bordered by island arcs, but those parts have been compressed, fractured, and distorted especially in the eastern Urals. The early Palaeozoic eastern margin is better preserved south of the polar region (65 °N) where shallow-water sediments can be found in the western Urals whilst the eastern Urals are characterised by deep-water deposits. The oldest known mid-ocean hydrothermal vent in the south-central part of the Urals clearly delimits the eastern extent. The straightness of the mountain chain is the result of continuous strike-slip movements during the Late Carboniferous to Early Permian (300–290 Ma).[19]

Baltic endemic faunas from the Early Ordovician have been found in Kazakhstan near the southern end of the eastern margin, or the triple junction between Baltica, the Mangyshlak Terrane, and the accretionary Altaids. Here the Early Palaeozoic rocks are buried under the Caspian Depression.[19]

See also

- Baltic Plate – Ancient tectonic plate from the Cambrian to the Carboniferous Period

References

Notes

- Cocks & Torsvik 2005, Abstract

- E.g. Torsvik & Cocks 2005, Norway's earliest times, pp. 74–75

- Bogdanova et al. 2008, The crustal segments of the East European Craton, pp. 2–3

- Torsvik et al. 1996, Abstract

- Pärnaste, Helje; Bergström, Jan (1 November 2013). "The asaphid trilobite fauna: Its rise and fall in Baltica". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 389: 64–77. Bibcode:2013PPP...389...64P. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2013.06.007.

- Cocks & Torsvik 2005, The margins of Baltica, p. 41

- Gee, Bogolepova & Lorenz 2006, p. 507

- Torsvik et al. 1992, Introduction, pp. 133–137

- Walderhaug, Torsvik & Halvorsen 2007, Baltica and Varangian Glaciations, pp. 946–947; Fig. 12, p. 946

- Miller et al. 2011, Abstract

- Colpron & Nelson 2009, Terranes of Siberian, Baltican and Caledonian affinities, pp. 280–281

- Johansson 2009, Abstract

- Cawood & Pisarevsky 2017, Abstract

- Hacker et al. 2010, Western Gneiss Region, pp. 150–151

- Spengler et al. 2009, Abstract; Conclusion and implications, pp. 33–34

- Cocks & Torsvik 2005, The margins of Baltica, p. 42–44

- Brown et al. 2006, Geological framework of the Uralides, p. 262; For a model of the arc-continent collision see Puchkov 2009, Fig. 12, p. 178; Fig. 14, p. 180

- Brown et al. 2006, The Paleozoic continental margin of Baltica in the Southern Urals, pp. 262–266

- Cocks & Torsvik 2005, The margins of Baltica, p. 44–45

Sources

- Bogdanova, S. V.; Bingen, B.; Gorbatschev, R.; Kheraskova, T. N.; Kozlov, V. I.; Puchkov, V. N.; Volozh, Y. A. (2008). "The East European Craton (Baltica) before and during the assembly of Rodinia" (PDF). Precambrian Research. 160 (1–2): 23–45. Bibcode:2008PreR..160...23B. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2007.04.024. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- Brown, D.; Spadea, P.; Puchkov, V.; Alvarez-Marron, J.; Herrington, R.; Willner, A. P.; Hetzel, R.; Gorozhanina, Y.; Juhlin, C. (2006). "Arc–continent collision in the Southern Urals". Earth-Science Reviews. 79 (3–4): 261–287. Bibcode:2006ESRv...79..261B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.512.9898. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2006.08.003.

- Cawood, P. A.; Pisarevsky, S. A. (2017). "Laurentia-Baltica-Amazonia relations during Rodinia assembly" (PDF). Precambrian Research. 292: 386–397. Bibcode:2017PreR..292..386C. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2017.01.031. hdl:10023/12665. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- Cocks, L. R. M.; Torsvik, T. H. (2005). "Baltica from the late Precambrian to mid-Palaeozoic times: the gain and loss of a terrane's identity" (PDF). Earth-Science Reviews. 72 (1–2): 39–66. Bibcode:2005ESRv...72...39C. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.04.001. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- Colpron, M.; Nelson, J. L. (2009). "A Palaeozoic Northwest Passage: Incursion of Caledonian, Baltican and Siberian terranes into eastern Panthalassa, and the early evolution of the North American Cordillera" (PDF). Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 318 (1): 273–307. Bibcode:2009GSLSP.318..273C. doi:10.1144/SP318.10. S2CID 128635186. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-10. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- Gee, D. G.; Bogolepova, O. K.; Lorenz, H. (2006). "The Timanide, Caledonide and Uralide orogens in the Eurasian high Arctic, and relationships to the palaeo-continents Laurentia, Baltica and Siberia". Geological Society, London, Memoirs. 32 (1): 507–520. doi:10.1144/GSL.MEM.2006.032.01.31. S2CID 129149517. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Hacker, B. R.; Andersen, T. B.; Johnston, S.; Kylander-Clark, A. R.; Peterman, E. M.; Walsh, E. O.; Young, D. (2010). "High-temperature deformation during continental-margin subduction & exhumation: The ultrahigh-pressure Western Gneiss Region of Norway" (PDF). Tectonophysics. 480 (1–4): 149–171. Bibcode:2010Tectp.480..149H. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2009.08.012. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- Johansson, Å. (2009). "Baltica, Amazonia and the SAMBA connection—1000 million years of neighbourhood during the Proterozoic?". Precambrian Research. 175 (1–4): 221–234. Bibcode:2009PreR..175..221J. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2009.09.011. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- Miller, E. L.; Kuznetsov, N.; Soboleva, A.; Udoratina, O.; Grove, M. J.; Gehrels, G. (2011). "Baltica in the Cordillera?". Geology. 39 (8): 791–794. Bibcode:2011Geo....39..791M. doi:10.1130/G31910.1. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- Puchkov, V. N. (2009). "The evolution of the Uralian orogen". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 327 (1): 161–195. Bibcode:2009GSLSP.327..161P. doi:10.1144/SP327.9. S2CID 129439058. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- Spengler, D.; Brueckner, H. K.; van Roermund, H. L.; Drury, M. R.; Mason, P. R. (2009). "Long-lived, cold burial of Baltica to 200 km depth" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 281 (1–2): 27–35. Bibcode:2009E&PSL.281...27S. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.02.001. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- Torsvik, T. H.; Cocks, L. R. M. (2005). "Norway in space and time: a centennial cavalcade". Norwegian Journal of Geology. 85: 73–86. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.708.9258.

- Torsvik, T. H.; Smethurst, M. A.; Meert, J. G.; Van der Voo, R.; McKerrow, W. S.; Brasier, M. D.; Sturt, B. A.; Walderhaug, H. J. (1996). "Continental break-up and collision in the Neoproterozoic and Palaeozoic—a tale of Baltica and Laurentia" (PDF). Earth-Science Reviews. 40 (3–4): 229–258. Bibcode:1996ESRv...40..229T. doi:10.1016/0012-8252(96)00008-6. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Torsvik, T. H.; Smethurst, M. A.; Van der Voo, R.; Trench, A.; Abrahamsen, N.; Halvorsen, E. (1992). "Baltica. A synopsis of Vendian-Permian palaeomagnetic data and their palaeotectonic implications" (PDF). Earth-Science Reviews. 33 (2): 133–152. Bibcode:1992ESRv...33..133T. doi:10.1016/0012-8252(92)90023-M. hdl:2027.42/29743. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- Walderhaug, H. J.; Torsvik, T. H.; Halvorsen, E. (2007). "The Egersund dykes (SW Norway): A robust early Ediacaran (Vendian) palaeomagnetic pole from Baltica". Geophysical Journal International. 168 (3): 935–948. Bibcode:2007GeoJI.168..935W. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2006.03265.x.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

_political.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)