Workload

The term workload can refer to several different yet related entities.

An amount of labor

An old definition refers to workload as the amount of work an individual has to do.[1] There is a distinction between the actual amount of work and the individual's perception of the workload. [1] To distinguish the two types, the term 'mental workload' (MWL) is often preferred, clearly indicating the latter type, which refers to the workload experienced by a human, regardless of the task's difficulty. This is because the same underlying task might generate two distinct mental responses and experiences, thus, different cognitive load amounts, even if executed by the same person. Many definitions of mental workload have been proposed in the years.[2] A more recent and operational definition is that "Mental workload (MWL) represents the degree of activation of a finite pool of resources, limited in capacity, while cognitively processing a primary task over time, mediated by external stochastic environmental and situational factors, as well as affected by definite internal characteristics of a human operator, for coping with static task demands, by devoted effort and attention".[2] This definition has emerged from a systematic review of the construct of mental workload by analysing many published research works and all the ad-hoc definitions that have emerged in the last 60 years. It has also been influenced by the Multiple Resource Theory, described below, and the notion of human, multiple resources. [3]

The assessment of operator workload has a strong impact on new human-machine systems design. By evaluating operator workload during the design of a new system, or iteration of an existing system, problems such as workload bottlenecks and overload can be identified. As the human operator is a central part of a human-machine system, correcting these problems is necessary to operate safe and efficient systems. An operating budget may include estimates of the expected workload for a specific activity.

'Workload' or 'cognitive load' is often confused with 'cognitive load theory'. The latter is referred to as the actual construct of Cognitive Load (CL), or mental workload (MWL). In contrast, the former is referred to a specific cognitivist learning theory within the larger field of pedagogy and instructional design.

Quantified effort

Workload can also refer to the total energy output of a system, particularly of a person or animal performing a strenuous task over time. One particular application of this is weight lifting/weights training, where both anecdotal evidence and scientific research have shown that it is the total "workload" that is important to muscle growth, as opposed to just the load, just the volume, or "time under tension". In these and related uses, "workload" can be broken up into "work+load", referring to the work done with a given load. In terms of weights training, the "load" refers to the heaviness of the weight being lifted (20 kg is a more significant load than 10 kg), and "work" refers to the volume, or the total number of reps and sets done with that weight (20 reps are more work than ten reps, but two sets of 10 reps are the same work as 1 set of 20 reps, its just that the human body cannot do 20reps of heavy weight without a rest, so its best to think of 2x10 as being 20 reps, with a rest in the middle).

This theory was also used to determine horse power (hp), which was defined as the amount of work a horse could do with a given load over time. The wheel that the horse turned in Watt's original experiment put a specific load on the horse's muscles, and the horse could do a certain amount of work with this load in a minute. Provided the horse was a perfect machine, it would be capable of a constant maximum workload. Increasing the load by a given percentage would decrease the possible work done by the same percentage so that it would still equal "1 hp". Horses are not perfect machines and, over short periods, are capable of as much as 14 hp, and over long periods of exertion, output an average of less than 1 hp.

The theory can also be applied to automobiles or other machines, which are slightly more "perfect" than animals. Making a car heavier, for instance, increases the load that the engine must pull. Likewise, making it more aerodynamic decreases drag, which also acts as a load on the car. Torque can be considered the ability to move a load, and the revs are how much work it can do with that load in a given amount of time. Therefore, torque and revs together create kilowatts or total power output. Total output can be related to the "workload" of the engine/car or how much work it can do with a given load. As engines are more mechanically perfect than animals' muscles and do not fatigue similarly, they will conform much more closely to the formula that if you apply more load, they will do less work, and vice versa.

Occupational stress

In an occupational setting, workload can be stressful and serve as a stressor for employees. Three aspects of workload can be stressful.

- Quantitative workload or overload: Having more work to do than can be accomplished comfortably.

- Qualitative workload: Having work that is too difficult.

- Underload: Having work that fails to use a worker's skills and abilities.[4]

Workload has been linked to a number of strains, including anxiety, physiological reactions such as cortisol, fatigue,[5] backache, headache, and gastrointestinal problems.[6]

Workload as a work demand is a major component of the demand-control model of stress.[7] This model suggests that jobs with high demands can be stressful, especially when the individual has low control over the job. In other words, control serves as a buffer or protective factor when demands or workload is high. This model was expanded into the demand-control-support model, which suggests that the combination of high control and high social support at work buffers the effects of high demands.[8]

As a work demand, workload is also relevant to the job demands-resources model of stress that suggests that jobs are stressful when demands (e.g., workload) exceed the individual's resources to deal with them.[9][10]

Theory and modelling

There is no one agreed definition of mental workload and consequently not one agreed method of assessing or modelling it.[2] One example definition by Hart and Staveland (1988) describes workload as "the perceived relationship between the amount of mental processing capability or resources and the amount required by the task". A more generally applicable operational definition of workload is that "Mental workload (MWL) represents the degree of activation of a finite pool of resources, limited in capacity, while cognitively processing a primary task over time, mediated by external stochastic environmental and situational factors, as well as affected by definite internal characteristics of a human operator, for coping with static task demands, by devoted effort and attention".[2]

Workload modelling is the analytical technique used to measure and predict workload. The main objective of assessing and predicting cognitive workload is to achieve an evenly distributed, manageable workload and to avoid overload or underload. Another aspect of workload is the mathematical predictive models used in human factors analysis to support the design and assessment of safety-critical systems.

Theories

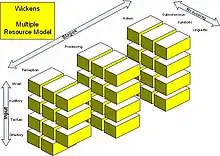

Wickens' (1984) multiple resource theory (MRT) model [11] is illustrated in figure 1:

Wickens' MRT proposes that the human operator does not have one single information processing source that can be tapped but several different pools of resources that can be tapped simultaneously. Each box in figure 1 indicates one cognitive resource. Depending on the nature of the task, these resources may have to process information sequentially if the different tasks require the same pool of resources or can be processed in parallel if the task requires different resources.

Wickens' theory views performance decrement as a shortage of these different resources and describes humans as having limited capability for processing information. Cognitive resources are limited, and a supply and demand problem occurs when the individual performs two or more tasks that require a single resource (as indicated by one box on the diagram). Excess workload caused by a task using the same resource can cause problems, errors, or slower performance. For example, if the task is to dial the phone, then no excess demands are placed on any component. However, if another task is being performed simultaneously that demands the same component(s), the result may be an excess workload.

The relationship between workload and performance is complex. It is not always the case that as workload increases, performance decreases. Performance can be affected by workload being too high or too low (Nachreiner, 1995). A sustained low workload (underload) can lead to boredom, loss of situation awareness and reduced alertness. Also, as workload increases, performance may not decrease as the operator may have a strategy for handling task demands.

Wickens' theory allows system designers to predict when:

- Tasks can be performed concurrently.

- Tasks will interfere with each other.

- Increases in the difficulty of one task will result in a loss of performance of another task.

Like Wickens, McCracken and Aldrich (1984) describe the processing, not as one central resource but as several processing resources: visual, cognitive, auditory, and psychomotor (VCAP). All tasks can be decomposed into these components.

- The visual and auditory components are external stimuli that are attended to.

- The cognitive component describes the level of information processing required.

- The psychomotor component describes the physical actions required.

They developed rating scales for each VCAP component, which provide a relative rating of the degree to which each resource component is used.

Joseph Hopkins (unpublished) developed a training methodology. The background to his training theory is that complex skills are, in essence, resource conflicts where training has removed or reduced the conflicting workload demands, either by higher-level processing or by predictive time sequencing. His work is based on Gallwey (1974) and Morehouse (1977). The theory postulates that the training allows the different task functions to be integrated into one new skill. An example of this is learning to drive a car. Changing gear and steering are two conflicting tasks (i.e. both require the same resources) before they are integrated into the new skill of "driving". An experienced driver will not need to think about what to do when turning a corner (higher level processing) or may change gear earlier than required to give sufficient resources for steering around the corner (predictive time sequencing).

Creating a model

With any attempt at creating a workload model, the process begins with understanding the tasks to be modelled. This is done by creating a task analysis that defines:

- The sequence of tasks performed by individuals and team members.

- The timing and workload information associated with each task.

- Background scenario information.

Each task must be defined to a sufficient level to allow realistic physical and mental workload values to be estimated and to determine which resources (or combination of resources) are required for each task – visual, auditory, cognitive and psychomotor. A numerical value can be assigned to each based on the scales developed by McCracken and Aldrich.

These numerical values against each resource type are then entered into the workload model. The model sums the workload ratings within each resource and across concurrent tasks. The critical points within the task are therefore identified. When proposals are made for introducing new devices onto the current baseline activities, this impact can then be compared to the baseline. One of the most advanced workload models was possibly developed by K Tara Smith (2007). This model integrated the theories of Wickens, McCracken and Aldrich and Hopkins to produce a model that not only predicts the workload for an individual task but also indicates how that workload may change given the experience and training level of the individuals carrying out that task. Workload assessment techniques are typically used to answer the following types of questions: Eisen, P.S and Hendy, K.C. (1987):

- Does the operator have the capability to perform the required tasks?

- Does the operator have enough spare capacity to take on additional tasks?

- Does the operator have enough spare capacity to cope with emergencies?

- Can the task or equipment be altered to increase spare capacity?

- Can the task or equipment be altered to increase/decrease the amount of mental workload?

- How does the workload of a new system compare to the old system?

Cognitive workload in time-critical decision-making processes

It is well accepted that there is a relationship between the media by which information is transferred and presented to a decision maker and their cognitive workload. During times of concentrated activity, single-mode information exchange is a limiting factor. Therefore, the balance between the different information channels (most commonly considered visual processing and auditory, but could also include haptic, etc.) directly affects cognitive workload (Wickens 1984). In a time-critical decision situation, this workload can lead to human error or delayed decisions to accommodate the processing of the relevant information. (Smith, K.T. & Mistry, B. 2009).[12] Work conducted by K Tara Smith has defined some terms relating to the workload in this area. The two main concepts relating to workload are:

- workload debt - which is when an individual's cognitive workload is too high to complete all relevant tasks in the time available, and they decide (either consciously or subconsciously) to postpone one or more tasks (usually low priority tasks) to enable them to decide on the required timeframe.

- workload debt cascade - when, because of the high workload, the postponed tasks mount up so that the individual cannot catch up with the tasks they are required to do, causing failure in subsequent activities.

See also

Notes

- Jex, S. M. (1998). Stress and job performance: Theory, research, and implications for managerial practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Longo L., Wickens C. D., Hancock G. and Hancock P. A. (2022). "Human Mental Workload: A Survey and a Novel Inclusive Definition". Front. Psychol. 12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.883321. hdl:10147/635016. PMID 35719509.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license. - Wickens, C. D. (2008). Multiple resources and mental workload. Hum. Factors 50, 449–455. doi: 10.1518/001872008X288394

- Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1978). The social psychology of organizations 2ed. New York City: John Wiley.

- Ganster D. C., Rosen C. C. (2013). "Work stress and employee health: A multidisciplinary review". Journal of Management. 39 (5): 1085–1122. doi:10.1177/0149206313475815. S2CID 145477630.

- Nixon A. E., Mazzola J. J., Bauer J., Krueger J. R., Spector P. E. (2011). "Can work make you sick? A meta-analysis of the relationships between job stressors and physical symptoms". Work & Stress. 25 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1080/02678373.2011.569175. S2CID 144068069.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Karasek R. A. (1979). "Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain-implications for job redesign". Administrative Science Quarterly. 24 (2): 285–308. doi:10.2307/2392498. JSTOR 2392498.

- Johnson J. V., Hall E. M. (1988). "Job strain, work place social support, and cardiovascular disease: A cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population". American Journal of Public Health. 78 (10): 1336–1342. doi:10.2105/ajph.78.10.1336. PMC 1349434. PMID 3421392.

- Demerouti E., Bakker A. B., Nachreiner F., Schaufeli W. B. (2001). "The job demands-resources model of burnout". Journal of Applied Psychology. 86 (3): 499–512. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499. PMID 11419809.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands-resources theory. In P. Y. Chen & C. L. Cooper (Eds.). Work and wellbeing Vol. III (pp. 37-64), Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell

- Wickens, C.D. (1984). "Processing resources in attention", in R. Parasuraman & D.R. Davies (Eds.), Varieties of attention, (pp. 63–102). New York: Academic Press.

- Smith, K.T., Mistry, B (2009) Predictive Operational Performance (PrOPer) Model. Contemporary Ergonomics 2009 Proceedings of the International Conference on Contemporary Ergonomics 2009 http://www.crcnetbase.com/doi/abs/10.1201/9780203872512.ch28