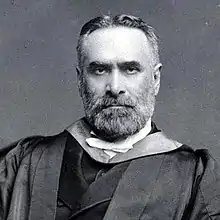

William Hastie

William Hastie MA DD (7 July 1842 – 31 August 1903)[1][2] was a Scottish clergyman and theologian. He produced the first English translation of the Universal Natural History and Theory of Heaven, by Immanuel Kant. Hastie led the General Assembly's Institution in Calcutta, where he was credited with developing the Hindu advocate Swami Vivekananda. Hastie recovered from a ruinous libel case in Calcutta to become the Professor of Divinity at University of Glasgow.

William Hastie | |

|---|---|

William Hastie | |

| Born | William Hastie 7 July 1842 Wanlockhead, Dumfriesshire, Scotland |

| Died | 31 August 1903 (aged 61) Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Occupation(s) | Educator, translator and writer |

Early life and career

William Hastie was born on 7 July 1842 at Wanlockhead in Dumfriesshire, Scotland. He entered the University of Edinburgh in 1859 and graduated with an M.A. in Philosophy in the First Division in 1867 and further with a B.D. in 1869.[3][4]

He further studied at the University of Glasgow in 1870 and 1871, under John Caird, Professor of Divinity.[5] Hastie studied further in the Netherlands and Germany and became fluent in German. In 1875, he decided to become a probationer in the Church of Scotland so that he could teach abroad. Three years later, he was on a ship bound from Liverpool to Calcutta.[6]

India

In 1878 Hastie was appointed principal of the General Assembly's Institution in Calcutta.[4][7]

According to a legend, Narendranath Datta (the future Swami Vivekananda) was first introduced to Indian mystic Ramakrishna in a literature class, given by Hastie. While lecturing on William Wordsworth's poem, The Excursion, Hastie suggested to his students that they should visit Ramakrishna of Dakshineswar to understand the true meaning of the phenomenon of "trance". Rajagopal Chattopadhyaya attributes the legend to a classmate of Narendranath, Haramohan Mitra.[8] Hastie must have inspired his students, because several went on to find out more about meditation.[6]

Hastie showed an interest in his students. For instance, despite Narendranath Datta's chain-smoking, he remarked, "Narendra Nath Dutta is really a genius. I have traveled far and wide, but have never yet come across a lad of his talent and possibilities, even in the German universities amongst philosophy students".[6]

Hastie was ambitious, planning to build his own mission centre, but he fell out with his own employer's missionaries. When this became public knowledge, the missionaries were the ones supported in their complaints. Hastie then published an ill-timed collection of his letters under the title "Hindu Idolatry and English Enlightenment", which annoyed the Hindu community and caused someone to assault him in the street.[9] Hastie was described as a stubborn idealist and his discussions and objections to blind faith, bigotry, and rituals were not well received. His objections to rituals were taken up by Bankim Chatterjee and became a public argument.[6]

Libel charge and imprisonment

In parallel with his other troubles, Hastie fell out with a Miss Pigot who was employed by the Scottish Ladies' Association.[9] One source claims that it was Hastie who was trying to expose the poor management and morals of Pigot, Superintendent of the Zenana Mission School and Orphanage.[6] Hastie claimed that the (allegedly) Eurasian Pigot was illegitimate and that she was having an affair with both Kali Charan Banerjee of the Free Church College and Professor James Wilson of the General Assembly's Institution.[10]

Hastie and Pigot both went to court, with Hastie defending himself on libel charges by calling on supportive witnesses. The case was sent to appeal, and eventually Hastie and his witnesses were rebuked.[11] He unsuccessfully appealed to the church in Scotland. He had already been dismissed in 1884 and had no way of covering his costs and the fine that the court levied against him. As a result, Hastie was imprisoned in Calcutta in 1885 and was released only when he went bankrupt.[9] Contemporary commentators have put the case down to Hastie's sexual jealousy, as he suspected one of Pigot's alleged partners - Kalicharan Banerjee - of writing articles that disagreed with Hastie's theology.[10] The case has been studied by Professor Kenneth Ballhatchet.[12]

The secular Indian and the English Press in Calcutta sided with Miss Pigot, but the Indian missionary establishment's views were summarised by Rev. J. Hudson in the magazine Harvest Field, where he discussed the case and concluded that Pigot was not immoral but "lacking in female delicacy". Hudson interwove this observation with hints of Pigot's poor management. Later analysis has seen Hastie as a "classic case of sexual jealousy" being projected from his intellectual rivalry onto sexual rivalry.[10] Hastie returned to Wanlockhead in 1885 to work as a translator.[7]

Final years

_aan_Nicolaas_Beets_(1814-1903)_LTK_BEETS_A_1.pdf.jpg.webp)

In 1892 Hastie was chosen to deliver the Croall Lectures at the University of Edinburgh. The University also awarded him the honorary degree of DD on 13 April 1894.[3] In 1895, Hastie succeeded William Purdie Dickson as the professor of divinity at University of Glasgow.[4][5]

In 1900 he produced the first English translation of the Allgemeine Naturgeschichte und Theorie des Himmels by Immanuel Kant. Hastie described the work "as the most wonderful and enduring product of [Kant's] genius."[13]

He lived his final years at 23 Queens Crescent in the Blacket district of south Edinburgh.[14]

Hastie died suddenly in Edinburgh on 31 August 1903 and was buried in his hometown.[9] An enthusiastic biography, The Life of Professor Hastie by Donald MacMillan, was published at Paisley in 1926.

Bibliography

- William Hastie (1881). The elements of philosophy.

- William Hastie (1883). Hindu Idolatry and English Enlightenment: Six Letters Addressed to Educated Hindus Containing a Practical Discussion of Hinduism. Thacker, Spink and Company.

- William Hastie (1899). Theology as a science and its present position and prospects in the Reformed Church. J. MacLehose.

- William Hastie (1904). The Theology of the Reformed Church in Its Fundamental Principles. T. & T. Clark.

References

- Robert Crawford (31 December 2008). Scotland's Books: A History of Scottish Literature. Oxford University Press. p. 523. ISBN 978-0-19-988897-9.

- Peter France (2001). The Oxford Guide to Literature in English Translation. Oxford University Press. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-19-924784-4.

- Bayne, Thomas (1912). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). Vol. 2. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- General Assembly's Institution (1845–1907): Principals in 175th Year Commemoration Volume. Scottish Church College, April 2008, p. 568.

- "William Hastie". The University of Glasgow Story. University of Glasgow. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- Jaiboy, Joseph (23 June 2002). "Master visionary". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 3 July 2003. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- Abraham, John. "Scottish Church College – Glimpses of College History" (PDF). article. Scottish Church College. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- Rajagopal Chattopadhyaya (1 January 1999). Swami Vivekananda in India: A Corrective Biography. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-81-208-1586-5.

- H. C. G. Matthew, 'Hastie, William (1842–1903)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 27 Nov 2013

- Kent, Eliza F. (2004). Converting women : gender and Protestant Christianity in colonial South India ([Reprint]. ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195165071.

- A version of the trial transcript is available in the Gale MOML Print Editions series: The Pigot Case, Report of the Case Pigot vs. Hastie as Before the High Court Calcutta, Calcutta 1884. What little is known about Miss Pigot can be seen at https://misspigot.com.

- Ballhatchet, Kenneth. Race, Sex and Class under the Raj: Imperial Attitudes and Policies and their Critics, 1793-1905. London, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1980. pp. 112-116. See also Western women and imperialism: complicity and resistance, edited by Nupur Chaudhuri and Margaret Strobel. Bloomington: Indiana University Press c.1992. p. 114.

- Michael J. Crowe (1999). The Extraterrestrial Life Debate, 1750–1900. Courier Dover Publications. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-486-40675-6.

- Edinburgh Post Office Directory 1902

Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee, Sidney, ed. (1912). "Hastie, William". Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee, Sidney, ed. (1912). "Hastie, William". Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

External links

Works by or about William Hastie at Wikisource

Works by or about William Hastie at Wikisource- Works by or about William Hastie at Internet Archive