William Forster (Australian politician)

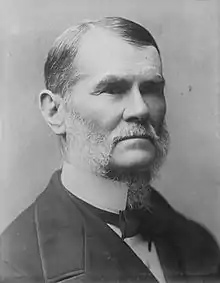

William Forster (16 October 1818 – 30 October 1882) was a pastoral squatter, colonial British politician, Premier of New South Wales from 27 October 1859 to 9 March 1860, and poet.

William Forster | |

|---|---|

| |

| 4th Premier of New South Wales | |

| In office 27 October 1859 – 9 March 1860 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Governor | Sir William Denison |

| Preceded by | Charles Cowper |

| Succeeded by | John Robertson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 16 October 1818 Madras, Mughal Empire |

| Died | 30 October 1882 (aged 64) Edgecliff, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Spouses | Eliza Jane Wall (m. 1846)Maud Edwards (m. 1873) |

Early life

Forster was born in Madras, India, the son of Thomas Forster, army surgeon, and his wife Eliza Blaxland, daughter of Gregory Blaxland. His parents married in Sydney and travelled to India in 1817, Wales in 1822, Ireland in 1825 and settled down in 1829 in Brush Farm,[1] Eastwood, built by Blaxland in about 1820, and the birthplace of the Australian wine industry.[2] He continued his education in Australia at W. T. Cape's school and The King's School.

Pastoral squatter

Forster became a squatter and took up pastoral holdings near the Clarence River and later on the Burnett River (near Hervey Bay). In 1840, with his uncle Gregory Blaxland Jnr, he led his herds of sheep down from the New England tablelands into the Clarence Valley to set up a sheep station. Due to the high level of Aboriginal resistance he named his pastoral holding Purgatory. Blaxland, who took up land adjoining Forster's run, encountered a similar situation and named his holding Pandemonium. The names of these pastoral leases were later changed to Geergarow and Nymboida respectively.[3] Forster was appointed a magistrate in 1842. In 1848, Forster and Blaxland advanced further north looking to exploit more land for livestock raising. They chose an area along the lower reaches of the recently surveyed Burnett River. They named this pastoral lease Tirroan and it was extensive in size, covering most of the modern day Bundaberg region. On 4 June 1849, two of his young shepherds were murdered by local Aboriginal's, and in retaliation, Blaxland led a punitive expedition which killed a number of Aboriginals.[4] When this occurred, Forster had been recently sacked from his magistrate position, with no reason given.[5] In 1850, further frontier violence occurred in which Blaxland was clubbed to death. Forster organised another punitive mission which resulted in a large massacre of Aboriginals.[4] He sold out of the Tirroan property not long after, but remained in the Wide Bay-Burnett region until 1856, retaining ownership over a number of other pastoral leases.[6] In 1867 he still controlled over 30,000 hectares in Queensland.[1]

Views on Aboriginals, colonisation and the Native Police

Forster had clear opinions on the people, including Aboriginal Australians. He stated that "Their rude arts and manufactures, their language, their manners and customs, are all distinctly primitive" and "to preserve, as an organic whole or nation, any inferior race, even one of superior tenacity, when the conflict for room arises, is plainly impossible".[7]

Forster took the view that there were three stages in colonisation. The first was an intermittent type of warfare between "the blacks" and the occupiers, the second was "a kind of open war", and the final stage being an acceptance of defeat by the original owners of the land.[8] During an NSW Legislative Assembly Select Report on the "Murders by the Aborigines on the Dawson River", when asked for the cause, Forster stated "I should say murders of that kind must always be expected on the frontier of a Colony like this, more or less. The great number of murders committed recently may be owing to peculiar causes; but that murders must occur in taking up new country, by collisions between the whites and the aborigines, is a necessity almost of that sort of colonization."[9]

In 1848, the colonial Government of New South Wales attempted to reduce the violence of the Aboriginal population by organising a paramilitary Native Police force to subdue them, Forster was strongly and publicly critical of its methods and its commandant, Walker. In particular, Forster was against allowing Aboriginals that have committed murders to stay on the property as workers, stating that "Is it to be supposed that the admission of known murderers to a station can be agreeable to those resident upon it". Forster ran a very public campaign against Walker which resulted in the Commandant being sacked.[10][11]

Parliamentary career

When responsible government was granted, Forster was elected to the first Legislative Assembly in 1856 as member for United Counties of Murray and St Vincent. From 1859 to 1860 he represented Queanbeyan.[12] and, though conservative in tendencies, he opposed the nominee upper house and advocated railway construction on a large scale. He did not believe in party government and endeavoured to maintain an independent position but, when the Cowper government was defeated in 1859, he became leader of a ministry which lasted for only a little more than four months.[13]

Forster won a by-election for East Sydney in May 1861 and in October 1863 was again asked to form a ministry. He was unable to do so but became Colonial Secretary in (Sir) James Martin's ministry until February 1865. From 1864 to 1869, Forster was member for Hastings. Though he had been a bitter opponent of John Robertson he was given a seat in Robertson's first cabinet as Secretary for Lands in October 1868 but retained his portfolio for only three months after Charles Cowper became Premier in January 1870. He was member for Queanbeyan from 1869 to 1872, Illawarra from 1872 to 1874 and Murrumbidgee from 1875 to 1876.[12]

In February 1875, Forster became Colonial Treasurer in Robertson's third ministry and a year later was appointed Agent-General for New South Wales in London. After the third Parkes ministry was formed in December 1878, Forster was recalled because of his dispute with Thomas Woolner over his commission for a statue of James Cook for Hyde Park, Sydney, the offence he gave to London society by wearing bushman's clothes and speaking against the federation of Australia.[1] He returned to New South Wales, was elected for Gundagai, and was offered and declined the position of Leader of the Opposition.[13]

Forster was described in his youth as a "sallow, thin, saturnine young gentleman". He was not a great orator but was a debater of ability, though his habit of indulging in bitter personalities detracted from the effectiveness of his speeches. James Martin once described him as "disagreeable in opposition, insufferable as a supporter, and fatal as a colleague" but, however true that may have been, it was only one side of his character.[13]

Poet

From 1844 onwards Forster contributed significantly to Robert Lowe's the Atlas, including The Devil and the Governor, a poem attacking Governor Gipps, described as one of the best Australian satirical poems written in the 19th century.[1] He also contributed to Henry Parkes' The Empire and other papers.[13]

Forster did not publish anything in book form until towards the end of his life. His one work in prose, Political Presentments, which appeared in London in 1878, includes able discourses on the working of parliament, the development of democracy in Europe, and the political situation of the time. His volumes in verse were The Weirwolf: a Tragedy (1876), The Brothers: a Drama (1877), Midas (1884),[14] works of a vigorous and poetic mind, which in spite of their length can still be read with interest.[13]

Family life and legacy

In 1846 Forster married Eliza Wall and he settled with her on Brush Farm in 1856. They had two sons and six daughters, including World War I surgeon Laura Forster, before Eliza died in 1862. In 1873 he married Maud Julia Edwards and they had three sons and two daughters. He died in Edgecliff.[12]

The scientific name for the Queensland lungfish, Neoceradotus forsteri, was named by Gerard Krefft after Forster — due to his bringing the first specimen to Sydney.[15]

The town of Forster, New South Wales was named after him.[16]

See also

Notes

- Nairn, Bede. "Forster, William (1818–1882)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- "Brush Farm House, 19 Lawson Street, Eastwood". City of Ryde. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- "Clarence Rivers Historical Society". Daily Examiner. 5 June 1937. p. 8. Retrieved 17 October 2018 – via Trove.

- Laurie, Arthur. "Early Gin Gin and the Blaxland Tragedy" (PDF). University of Queensland Library. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "Audi Alteram Partem". The Moreton Bay Courier. Queensland, Australia. 31 March 1849. p. 2. Retrieved 17 October 2018 – via Trove.

- "Domestic Intelligence". The Moreton Bay Courier. Queensland, Australia. 5 January 1856. p. 2. Retrieved 19 October 2018 – via Trove.

- "Views of Colonisation". Australian Town and Country Journal. 1 May 1880. p. 26. Retrieved 20 October 2018 – via Trove.

- "1857 Report from the Select Committee on the Native Police Force". Caught in the Act. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "1858 Report from the Select Committee on the Murders by the Aborigines on the Dawson River" (PDF). aiatsis.gov.au. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Original correspondence. Native police". The Sydney Morning Herald. 21 August 1852. p. 3. Retrieved 20 October 2018 – via Trove.

- "The native police". Empire. 30 November 1854. p. 3. Retrieved 20 October 2018 – via Trove.

- "Mr William Forster (1818–1882)". Former members of the Parliament of New South Wales. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Forster, William (1818–1882)". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Mennell, Philip (1892). . The Dictionary of Australasian Biography. London: Hutchinson & Co – via Wikisource.

- "The naturalist". The Queenslander. Queensland, Australia. 27 September 1884. p. 507. Retrieved 19 October 2018 – via Trove.

- Reed, A.W. (1969) Place-Names of New South Wales: Their Origins and Meanings, p. 59. Sydney: A.H & A.W. Reed