William Anderson (RAAF officer)

Air Vice-Marshal William Hopton Anderson, CBE, DFC (30 December 1891 – 30 December 1975) was a senior commander in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). He flew with the Australian Flying Corps in World War I, earning the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Belgian Croix de guerre for his combat service with No. 3 Squadron on the Western Front in 1917. The following year he took command of No. 7 (Training) Squadron and, later, No. 3 Squadron. Anderson led the Australian Air Corps during its brief existence in 1920–21, before joining the fledgling RAAF. The service's third most-senior officer, he primarily held posts on the Australian Air Board in the inter-war years. He was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1934, and promoted to air commodore in 1938.

William Anderson | |

|---|---|

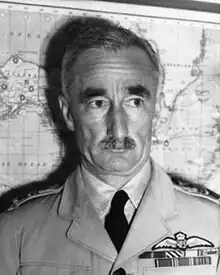

Air Vice-Marshal Anderson, c. 1940 | |

| Nickname(s) | "Andy"; "Mucker"[1] |

| Born | 30 December 1891 Kew, Victoria |

| Died | 30 December 1975 (aged 84) East Melbourne, Victoria |

| Allegiance | Australia |

| Service/ | Australian Flying Corps (1916–19) Australian Air Corps (1920–21) Royal Australian Air Force (1921–46) |

| Service years | 1910–1946 |

| Rank | Air Vice-Marshal |

| Unit | No. 1 Squadron AFC (1916) |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars | World War I World War II |

| Awards | |

At the outbreak of World War II, Anderson was Air Member for Supply. In 1940 he acted as Chief of the Air Staff between the resignation of Air Vice-Marshal Stanley Goble in January and the arrival of Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Burnett, RAF, the next month. He led the newly formed Central and Eastern Area Commands between December 1940 and July 1943, returning to the Air Board as Air Member for Organisation and Equipment from September 1941 to May 1942. Anderson was founding commandant of the RAAF Staff School from July to November 1943, after which he was appointed Air Member for Personnel. He again served as Staff School commandant from October 1944 until his retirement in April 1946. Known to his colleagues as "Andy" or "Mucker", Anderson died on his birthday in 1975.

Early life and World War I

Born on 30 December 1891 in Kew, a suburb of Melbourne, William Hopton Anderson was the third son of English-born surveyor Edward Anderson and his wife Florence (née Handfield), a native Victorian. Anderson was educated at Melbourne Church of England Grammar School, where he joined the cadet corps. In December 1910 he began his professional military career as a Royal Australian (Garrison) Artillery officer, based in Sydney. He transferred to the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force as a battery commander at Rabaul, in Australian-occupied German New Guinea, in March 1915.[1] The following January, Anderson joined the Australian Flying Corps (AFC) as a captain, sailing to Egypt with No. 1 Squadron.[1] During April and May 1916 he was attached to No. 17 Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC).[2] He then undertook flying training in Britain, where he saw further service with the RFC. In August 1917 he was posted to No. 3 Squadron (designated No. 69 Squadron RFC by the British), operating Royal Aircraft Factory R.E.8 two-seat reconnaissance aircraft on the Western Front.[1][3]

From October 1917, No. 3 Squadron was heavily involved in artillery spotting, activity that left the slow R.E.8s vulnerable to attack by enemy fighters. Twice that month Anderson's plane was dived upon by several German aircraft. He was, in his own words, "too scared to think" on the first occasion, but both times managed to manoeuvre his plane so that his observer could hold off their opponents with Lewis gun fire until other R.E.8s came to their aid.[4][5] Anderson was spotting for artillery near the Messines Ridge on 6 December when he engaged a German two-seat DFW that observer John Bell was able to shoot down; it was No. 3 Squadron's first confirmed aerial victory.[6][7]

In January 1918, Anderson was given the temporary rank of major and posted to England to take charge of No. 7 (Training) Squadron AFC.[1] He was recommended for the Military Cross (MC) on 12 March for his achievements with No. 3 Squadron in France, the citation noting his "resolute fight" and "cool and capable flying" in evading attacks by enemy aircraft and successfully carrying out reconnaissance missions.[8] In the event, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) in the King's Birthday Honours promulgated in the London Gazette on 3 June, becoming the first Australian to receive the newly created decoration.[9][10] He was also awarded the Belgian Croix de guerre, gazetted on 9 July.[11] Anderson returned to France in October 1918 as commanding officer of No. 3 Squadron.[1][12] The unit converted to Bristol Fighters the same month, and flew its last operation the morning of 11 November; it was subsequently employed in transporting mail for Australian forces in Europe.[13]

Inter-war years

Anderson relinquished command of No. 3 Squadron in January 1919 and returned to Australia two months later.[14] He was mentioned in despatches on 11 July.[15] In December the AFC was disbanded, to be replaced on 1 January 1920 by the short-lived Australian Air Corps (AAC), which was, like the AFC, a branch of the Army. The AFC's senior officer, Lieutenant Colonel Richard Williams, was still in England, and Anderson was appointed commander of the AAC, a position that also put him in charge of the Central Flying School (CFS) at Point Cook, Victoria.[16][17] As Anderson was on sick leave at the time of the appointment, Major Rolf Brown temporarily assumed command; Anderson took over on 19 February.[18] The AAC was an interim organisation intended to exist until the establishment of a permanent Australian air service.[19] In September 1920, Anderson piloted one of two Airco DH.9A bombers detailed to search for the schooner Amelia J., which had disappeared on a voyage from Newcastle to Hobart. Anderson safely completed his search without locating the lost schooner but the other DH.9A disappeared with its two-man crew, the only fatalities suffered by the AAC.[20]

On 31 March 1921, Anderson joined the newly formed Australian Air Force ("Royal" being added in August) as a squadron leader, becoming its third most-senior officer after Williams and former Royal Naval Air Service pilot Stanley Goble, both now wing commanders.[12][21] During 1921, Anderson commanded the RAAF's Point Cook base and Point Cook's two major units, No. 1 Flying Training School (No. 1 FTS)—the successor to CFS—and No. 1 Aircraft Depot (No. 1 AD).[1][22] Over the next four years he served as Director of Personnel and Training and as Chief of the Administrative Staff (Second Air Member) on the RAAF's controlling body, the Air Board, usually when Goble was away on overseas postings.[23][24] In April 1922, Anderson took part in the new service's first army co-operation exercise, piloting a DH.9 with Flight Lieutenant Adrian Cole, who spotted for artillery firing from an emplacement at Queenscliff, Victoria.[25] A year later, Anderson proposed a dedicated workshop for research and development, which was established as the RAAF Experimental Section at Point Cook in January 1924.[26]

_1938-39.jpg.webp)

The young Air Force staged many public displays in its early years; on one such occasion over the Melbourne suburb of Essendon in September 1924, Anderson, Flight Lieutenant Ray Brownell and another pilot took part in a mock dogfight while Flight Lieutenant Harry Cobby gave a demonstration of balloon busting.[27] That December, Anderson and Brownell interviewed Reg Pollard and Frederick Scherger, two undergraduates at the Royal Military College, Duntroon, who had applied to transfer to the RAAF; Scherger was selected, and went on to become the RAAF's first air chief marshal, while Pollard rose to become Chief of the General Staff. Scherger was also the first member of the Duntroon graduating class to transfer direct to the Air Force; previous such transfers had involved graduates already serving in the Army.[28] During 1925–26, Anderson again took command of No. 1 FTS, as well as occupying a position on the Air Board as Air Member for Personnel. He was posted to England between 1927 and 1929, attending RAF Staff College, Andover, and serving as air liaison officer (ALO) to the British Air Ministry. In March 1927 he was promoted to wing commander.[1][23] As ALO in 1928, he provided information to the Air Board concerning shortcomings of the de Havilland Hound light day bomber, then being strongly considered for the RAAF, that led to the Westland Wapiti being ordered instead.[29]

Returning to Australia in mid-1929, Anderson was for a short time in charge of No. 1 AD, now based at RAAF Station Laverton, Victoria, before appointment to the Air Board as Air Member for Supply in October.[1][30] He spent most of the 1930s in this position, aside from an acting role as Air Member for Personnel from January 1933 to June 1934, and attendance at the Imperial Defence College, London, the following year.[23][31] As Anderson had no formal training in the supply field, Air Force historian Alan Stephens concluded that he relied heavily on the specialist knowledge of his experienced subordinate, the RAAF Director of Transport and Equipment, George Mackinolty.[32] According to the official history of the pre-war Air Force, Anderson was generally regarded with affection but was also described as being "not quite on the same wave length as others".[33] Fellow officer Joe Hewitt found him "admirable" but "so immersed in the minutiae of administration that some important policy matters languished" and "although courageous he was indecisive and loath to take disciplinary action".[1][34] Anderson's chronic shyness with women other than his unmarried sister also made him an object of fun in some quarters.[1][33] He was raised to group captain in December 1932 and air commodore in January 1938.[1] Appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 1933 King's Birthday Honours,[35] he was promoted Commander in the same order (CBE) in the 1934 New Year Honours.[36]

World War II

Anderson was still serving as Air Member for Supply when Australia declared war in September 1939.[37] On 9 January 1940 he was appointed acting Chief of the Air Staff (CAS), following the resignation of the incumbent, Air Vice-Marshal Goble. Anderson remained in the position until 10 February, when Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Burnett, seconded from the Royal Air Force (RAF), arrived to take over.[1][38] According to author Norman Ashworth, the Australian government had at this stage so little faith in the leadership of its Air Force that it had briefly considered offering temporary command of the service to the Royal Australian Navy's Second Naval Member, Commodore Maitland Boucher, RN, before deciding against such a "monumental slight to the senior ranks of the RAAF" and settling on Anderson.[39] After relinquishing his temporary position as CAS, Anderson briefly reverted to his previous role as Air Member for Supply before taking over as Air Member for Personnel (AMP) in March 1940; he was succeeded as AMP in November by Air Vice-Marshal Henry Wrigley.[40][41] The next month, Anderson took over from Air Commodore Cole as Air Officer Commanding (AOC) Central Area, with responsibility for air defence, protection of adjacent sea lanes, and aerial reconnaissance for most of New South Wales; he remained at this post until it was disbanded in August the following year.[42][43]

Promoted acting air vice-marshal in September 1941, Anderson resumed his position on the Air Board by replacing Air Marshal Williams as Air Member for Organisation and Equipment.[44] In May 1942, he was appointed AOC of the newly established Eastern Area, which was headquartered in Sydney and controlled seven squadrons in New South Wales and southern Queensland.[45][46] One of the area's main roles was anti-submarine warfare; its squadrons also included fighters and army co-operation aircraft.[47] Japanese submarine activity off the east coast peaked during April and May 1943.[48] RAAF Bristol Beauforts were credited with damaging a Japanese submarine on 19 June, but neither the Air Force nor the Navy was able to destroy any enemy submarines in coastal waters during 1943.[49] The efforts of the two services within the region Eastern Area covered were hampered by poor liaison and command arrangements, as well as the RAAF placing a relatively low priority on protecting merchant shipping.[50]

Anderson handed over command of Eastern Area to Air Commodore John Summers in July 1943.[51] That month Anderson became the inaugural commandant of the RAAF Staff School at Mount Martha, Victoria.[1][52] The school was instituted to further the training of officers at the squadron leader and wing commander level, whose basic education standards Anderson, among others, found sadly lacking.[53] The curriculum was largely based on the war staff course at the RAF Staff College.[52] In December Anderson was again appointed AMP, taking over from Air Commodore Frank Lukis, before returning to command the RAAF Staff School in September 1944.[41] He continued in the latter role until being forcibly retired, along with several other senior Air Force commanders including Williams and Goble, in April 1946, ostensibly to make way for younger and equally qualified officers.[54][55] A confidential report in September 1944 had found Anderson "hard working, conscientious and loyal" but lacking in "constructive capacity and organising ability".[54] He was still four years below the statutory retirement age of fifty-seven for his substantive rank of air commodore.[56]

Retirement

Following his discharge from the RAAF as an honorary air vice-marshal, Anderson lived in East Melbourne. A lifelong bachelor, he shared a house with his sister, who also never married. From 1947 until 1971, Anderson served as honorary chairman of the Victorian branch of the Services Canteens Trust Fund.[1] On 31 March 1971, he was among a select group of surviving founder members of the RAAF who attended a celebratory dinner at the Hotel Canberra to mark the service's Golden Jubilee; his fellow guests included Air Marshal Williams, Air Vice-Marshal Wrigley, Air Commodore Hippolyte De La Rue, and Wing Commander Sir Lawrence Wackett.[57] Anderson died at his residence on his 84th birthday in 1975, and was buried in Boroondara General Cemetery, Kew.[1]

Notes

- Coulthard-Clark, "Anderson, William Hopton", pp. 53–54

- Cutlack, The Australian Flying Corps, p. 35

- Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, p. 9

- Cutlack, The Australian Flying Corps, p. 181

- Molkentin, Fire in the Sky, pp. 201–202

- Newton, Clash of Eagles, p. 16

- Molkentin, Fire in the Sky, pp. 224–225

- "Recommendation: Military Cross" (PDF). Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- "No. 30722". The London Gazette (Supplement). 3 June 1918. p. 6519.

- Sewell, Flying the Southern Skies, pp. 12–13

- "No. 30792". The London Gazette (Supplement). 9 July 1918. pp. 8169, 8189.

- Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 1, 16

- RAAF Historical Section, Units of the Royal Australian Air Force, p. 2

- "Air Vice-Marshal William Hopton Anderson". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- "No. 31448". The London Gazette (Supplement). 11 July 1919. pp. 8813, 8839.

- Sutherland, Command and Leadership, pp. 32–33

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 17–21

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 18, 20

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 17–18

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 25–26

- Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 31, 332

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 41

- "Honorary Air Vice-Marshals". Air Marshals of the RAAF. Royal Australian Air Force. Archived from the original on 6 July 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 359, 466–468

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 210

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 258

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 47–49

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 192, 202

- Stephens, Power Plus Attitude, pp. 37–38

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 367

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 466–468

- Stephens, Going Solo, p. 179

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 359–360

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 192

- "No. 33946". The London Gazette (Supplement). 2 June 1933. p. 3807.

- "No. 34010". The London Gazette (Supplement). 29 December 1933. p. 8.

- Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force!, p. 3

- Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force!, p. 20

- Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force!, pp. 18–21

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 468

- Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force!, p. 301

- Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force!, p. 303

- Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 91–92

- Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force!, p. 41

- Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force!, pp. 132–133

- Stephens, The RAAF in the Southwest Pacific Area, p. 61

- Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 141, 152

- Stevens, A Critical Vulnerability, p. 237

- Odgers, Air War Against Japan, pp. 152–153

- Stevens, A Critical Vulnerability, p. 241

- Ashworth, How Not to Run an Air Force! Volume One, p. 303

- "RAAF Staff College History". Australian Defence College. Department of Defence. Archived from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- Stephens, Power With Attitude, p. 83

- Helson, Ten Years at the Top, pp. 228, 233–237

- "Anderson, William Hopton". World War Two Nominal Roll. Department of Veterans' Affairs. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- Stephens, Power With Attitude, p. 92

- Stephens, Going Solo, pp. 451, 498

References

- Ashworth, Norman (2000). How Not to Run an Air Force! Volume One – Narrative (PDF). Canberra: RAAF Air Power Studies Centre. ISBN 0-642-26550-X.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1991). The Third Brother: The Royal Australian Air Force 1921–39 (PDF). North Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-442307-1.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1993). "Anderson, William Hopton (1891–1975)". In Ritchie, John (ed.). Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 13. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84512-6.

- Cutlack, F.M. (1941) [1923]. The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918 (11th edition): Volume VIII – The Australian Flying Corps in the Western and Eastern Theatres of War, 1914–1918. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. OCLC 220900299.

- Gillison, Douglas (1962). Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series Three (Air) Volume I – Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 2000369.

- Helson, Peter (2006). Ten Years at the Top (Ph.D thesis). Sydney: University of New South Wales. OCLC 225531223.

- Molkentin, Michael (2010). Fire in the Sky: The Australian Flying Corps in the First World War. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74237-072-9.

- Newton, Dennis (1996). Clash of Eagles. Kenthurst, New South Wales: Kangaroo Press. ISBN 0-86417-793-3.

- Odgers, George (1968) [1957]. Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series Three (Air) Volume II – Air War Against Japan 1943–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 246580191.

- RAAF Historical Section (1995). Units of the Royal Australian Air Force: A Concise History. Volume 2: Fighter Units. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-42794-9.

- Sewell, Hal (1999). Flying the Southern Skies. Glebe, New South Wales: Book House at Wild & Woolley. ISBN 1-74018-055-0.

- Stephens, Alan (1992). Power Plus Attitude: Ideas, Strategy and Doctrine in the Royal Australian Air Force 1921–1991 (PDF). Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-24388-0.

- Stephens, Alan (1995). Going Solo: The Royal Australian Air Force 1946–1971 (PDF). Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-42803-1.

- Stephens, Alan (2006) [2001]. The Royal Australian Air Force: A History. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-555541-7.

- Stephens, Alan, ed. (1993). The RAAF in the Southwest Pacific Area 1942–1945 (PDF). Canberra: RAAF Air Power Studies Centre. ISBN 0-642-19827-6.

- Stevens, David (2005). A Critical Vulnerability: The Impact of the Submarine Threat on Australia's Maritime Defence 1915–1954 (PDF). Canberra: Sea Power Centre – Australia. ISBN 0-642-29625-1.

- Sutherland, Barry, ed. (2000). Command and Leadership in War and Peace 1914–1975 – The Proceedings of the 1994 RAAF History Conference (PDF). Canberra: RAAF Air Power Studies Centre. ISBN 0-642-26537-2.