Weert dialect

Weert dialect or Weert Limburgish (natively Wieërts, Standard Dutch: Weerts [ʋeːrts]) is the city dialect and variant of Limburgish spoken in the Dutch city of Weert alongside Standard language. All of its speakers are bilingual with standard Dutch.[1] There are two varieties of the dialect: rural and urban. The latter is called Stadsweerts in Standard Dutch and Stadswieërts in the city dialect.[1] Van der Looij gives the Dutch name buitenijen for the peripheral dialect.[2]

| Weert dialect | |

|---|---|

| Wieërts | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈwiəʀts] |

| Native to | Netherlands |

| Region | Weert |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Limburg, Netherlands: Recognised as regional language as a variant of Limburgish. |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

Unless otherwise noted, all examples are in Stadsweerts.

Influence of Standard Dutch

Some dialect words are frequently replaced with their Standard Dutch counterparts, so that kippe /ˈkɪpə/ 'chickens', jullie /ˈjʏli/ 'you' (pl.) and vaak /ˈvaːk/ 'often' are often heard in place of the Limburgish words hinne /ˈɦɪnə/ (or hoendere /ˈɦundəʀə/), uch /ˈʏx/ and dék /ˈdɛk/.[3]

The voiced velar stop /ɡ/ is used less often by younger speakers, who merge it with the voiced velar fricative /ɣ/.[4] In Standard Dutch, [ɡ] occurs only as an allophone of /k/ before voiced stops, as in zakdoek [ˈzɑɡduk] 'handkerchief' and (in the Netherlands alone) as a separate phoneme in loanwords such as goal /ɡoːl/ 'goal' (in sports).

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ɲ ⟨nj⟩ | ŋ ⟨ng⟩ | |||

| Plosive/ affricate |

voiceless | p ⟨p⟩ | t ⟨t⟩ | tʃ ⟨tj⟩ | k ⟨k⟩ | ||

| voiced | b ⟨b⟩ | d ⟨d⟩ | (dʒ) ⟨dj⟩ | ɡ ⟨gk⟩ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | f ⟨f⟩ | s ⟨s⟩ | ʃ ⟨sj⟩ | x ⟨ch⟩ | ||

| voiced | v ⟨v⟩ | z ⟨z⟩ | (ʒ) ⟨zj⟩ | ɣ ⟨g⟩ | ɦ ⟨h⟩ | ||

| Liquid | l ⟨l⟩ | ʀ ⟨r⟩ | |||||

| Approximant | w ⟨w⟩ | j ⟨j⟩ | |||||

- /m, p, b/ are bilabial, whereas /f, v/ are labiodental.[1]

- /w/ is realized as a bilabial approximant [β̞] in the onset and as labio-velar [w] in the coda.[6] In this article, both are transcribed with ⟨w⟩, following the recommendations of Carlos Gussenhoven regarding transcribing the corresponding Standard Dutch phone.[7]

- In the syllable onset, /tʃ, dʒ, ʃ, ʒ/ can occur only in proper names and loanwords. In that position, their status is marginal.[4]

- /dʒ/ and /ʒ/ are found only in onsets of weak syllables.[4]

- /ɲ/ and /ɡ/ occur only intervocalically.[4]

- Word-initial /x/ is restricted to loanwords.[4]

- As in all areas with soft G, /x, ɣ/ are realized as post-palatal [ç˗, ʝ˗] (hereafter represented without the diacritics) when they are preceded or followed by a front vowel.[4]

- /ʀ/ is a voiced fricative trill, with the fricative component varying between uvular [ʁ͡ʀ] and post-velar [ɣ̠͡ʀ]. The fricative component is particularly audible in the syllable coda, where a partial devoicing to [χ͡ʀ̥ ~ x̠͡ʀ̥] also occurs.[4]

Vowels

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

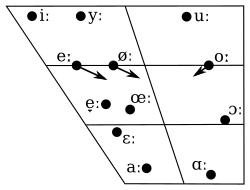

According to Peter Ladefoged, the vowel inventory of the dialect of Weert may be the richest in the world. It features 28 vowels, among which there are 12 long monophthongs (three of which surface as centering diphthongs), 10 short monophthongs and 6 diphthongs.[8] Such a large vowel inventory is a result of the loss of a contrastive pitch accent found in other Limburgish dialects, giving /ɛː/ and /ɑː/ a phonemic status. Those vowels correspond to the phonemically short /æ/ and /ɑ/ combined with Accent 2 in other dialects.[9]

| Front | Central | Back | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||||||

| short | long | short | long | short | short | long | ||

| Close | i ⟨ie⟩ | iː ⟨iê⟩ | y ⟨uu⟩ | yː ⟨uû⟩ | u ⟨oe⟩ | uː ⟨oê⟩ | ||

| Close-mid | ɪ̞ ⟨i⟩ | eː ⟨ee, î⟩ | øː ⟨eu, û⟩ | ʏ̽ ⟨u⟩ | (ʊ ⟨ó⟩) | oː ⟨oo⟩ | ||

| Mid | e̞ ⟨e⟩ | e̞ː ⟨ae⟩ | œ̝ ⟨ö⟩ | œ̝ː ⟨äö⟩ | ə ⟨e⟩ | |||

| Open-mid | ɛ ⟨é⟩ | ɛː ⟨ê⟩ | ɔ ⟨o⟩ | ɔː ⟨ao, ô⟩ | ||||

| Open | aː ⟨aa⟩ | ɑ ⟨a⟩ | ɑː ⟨â⟩ | |||||

| Diphthongs | closing | ɛɪ ⟨eî⟩ œʏ ⟨uî⟩ ʌʊ ⟨oû⟩ | ||||||

| centering | iə ⟨ieë⟩ yə ⟨uuë⟩ uə ⟨oeë⟩ | |||||||

In the table above, the vowels spelled with ⟨i⟩, ⟨u⟩, ⟨ö⟩ and ⟨äö⟩ are transcribed with phonetically explicit symbols. Elsewhere in the article, the diacritics are ignored for vowels other than /e̞/ and /e̞ː/, in case of which the lowering diacritic is essential in order to distinguish them from the close-mid /eː/.

- The Weert dialect features five phonetic degrees of openness among unrounded front vowels: close, close-mid, mid, open-mid and open.[11][12] The long unrounded front vowels /iː, eː, e̞ː, ɛː, aː/ differ mostly in height, in addition to the centering glide in /eː/.[12] Furthermore, /aː/ is clearly not front phonologically as it is subject to umlauting in diminutives and in other contexts, as in other Limburgish dialects. This suggests that it is phonologically central, as in Hamont as well as the vowel transcribed with the same symbol in German. This contrast between the phonologically central /aː/ and the phonologically back /ɑː/ surfaces as a phonetic front-back distinction, as /aː/ is phonetically near-front [a̠ː], whereas /ɑː/ is near-back [ɑ̟ː].[13]

- The distinction between /ɪ/, /e̞/ and /ɛ/ is a genuine distinction between close-mid, mid and open-mid vowels of the same length, roundedness and very similar backness: [ɪ̞, e̞, ɛ].[11][12] It is much like the distinction found in the Kensiu language. The close-mid /ɪ/ is transcribed as such (rather than with ⟨e⟩) due to the fact that ⟨e⟩ is typically used for tense/free vowels in Dutch dialectology, whereas /ɪ/ is lax/checked, much like /ɪ/ in Standard Dutch.

- The phonetic value of the symbol ⟨ʏ⟩ is far removed from its canonical IPA value, being a close-mid central vowel: [ɵ] (transcribed as a mid-centralized [ʏ] in the table above: [ʏ̽]).[13] The symbol ⟨ʏ⟩ is used here because it is a phonological front vowel, as in other dialects of Limburgish.

- Older speakers may have an additional vowel /ʊ/, giving rise to a phonemic contrast between the short closed O /ʊ/ (spelled ⟨ó⟩) and the short open O /ɔ/ (spelled ⟨o⟩). Other speakers have just three short back vowels /u, ɔ, ɑ/, as in Standard Dutch.[13] Elsewhere in the article, the difference is not transcribed and ⟨ɔ⟩ is used for both vowels.

- Some speakers are not secure in the distribution of /e̞/ vs. /ɛ/ as well as /ʏ/ vs. /œ/. In the future, this may lead to a merger of the two pairs, leaving a short vowel system that is exactly the same as in Standard Dutch (phonetic details aside).[13]

- As in other Limburgish dialects, /ɔ(ː)/ umlauts to /œ(ː)/ and so it patterns with the phonetic mid vowels, rather than the phonetically open-mid /ɛ(ː)/.

- The centering diphthongs /iə, yə, uə/ (as in zieëve /ˈziəvə/ 'seven', duuër /ˈdyəʀ/ 'door' and doeër /ˈduəʀ/ 'through') often correspond to the close-mid /eː, øː, oː/ in the buitenijen variety: zeve /ˈzeːvə/, deur /ˈdøːʀ/, door /ˈdoːʀ/. The extensive usage of /eː, øː, oː/ in the buitenijen variety brings it considerably closer to Standard Dutch than Stadsweerts. The varieties spoken in Nederweert and Ospel also use /eː, øː, oː/ in this context. The difference is systematic, though it does not occur throughout the entire vocabulary of words with those vowels. For instance, the word meaning 'residence' or 'house' varies between woeëning /ˈwuənɪŋ/ and wuuëning /ˈwyənɪŋ/ in both varieties, rather than being woning /ˈwoːnɪŋ/ or weuning /ˈwøːnɪŋ/ in the buitenijen variety.[1][14]

Taking all of that into consideration, the vocalic phonemes of the Weert dialect can be classified much like those found in other Limburgish dialects. Peter Ladefoged says that the Weert dialect is an example of a language variety that needs five height features to distinguish between /i(ː)/, /ɪ, eː/, /e̞(ː)/, /ɛ(ː)/ and /aː/, which are [high], [mid-high], [mid], [mid-low] and [low], respectively.[11]

| Front | Central | Back | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | ||||||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | ||

| Close | i ⟨ie⟩ | iː ⟨iê⟩ | y ⟨uu⟩ | yː ⟨uû⟩ | u ⟨oe⟩ | uː ⟨oê⟩ | |||

| Close-mid | ɪ ⟨i⟩ | eː ⟨ee, î⟩ | ʏ ⟨u⟩ | øː ⟨eu, û⟩ | ə ⟨e⟩ | (ʊ ⟨ó⟩) | oː ⟨oo⟩ | ||

| Mid | e̞ ⟨e⟩ | e̞ː ⟨ae⟩ | œ ⟨ö⟩ | œː ⟨äö⟩ | ɔ ⟨o⟩ | ɔː ⟨ao, ô⟩ | |||

| Open-mid | ɛ ⟨é⟩ | ɛː ⟨ê⟩ | |||||||

| Open | aː ⟨aa⟩ | ɑ ⟨a⟩ | ɑː ⟨â⟩ | ||||||

| Diphthongs | closing | (ɛj ⟨ei⟩) | ɛɪ ⟨eî⟩ | (œj ⟨ui⟩) | œʏ ⟨uî⟩ | (ɑw ⟨ou⟩) | ʌʊ ⟨oû⟩ | ||

| centering | iə ⟨ieë⟩ | yə ⟨uuë⟩ | uə ⟨oeë⟩ | ||||||

In this table, vowels in the mid row correspond to the open-mid /ɛ, ɛː, œ, œː, ɔ, ɔː/ in other dialects. The two vowels in the open-mid row correspond to the open /æ/ in other dialects, which means that the open-mid row can be merged with the open row, leaving just four phonemic heights. In this article, five heights are assumed, following the sources. In his paper on the best IPA transcription of Standard Dutch, Gussenhoven has criticized the analysis of the open-mid /ɛ/ as phonologically open on the basis of the vowel being phonetically too close to be analyzed as open like /aː/ (which is front in Standard Dutch, just like in Weert).[15]

The vowel+glide sequences /ɛj/, /œj/ and /ɑw/ pattern as the short counterparts of /ɛɪ, œʏ, ʌʊ/ - see below.

Phonetic realization

- The long close-mid /eː, øː, oː/ often feature a centering glide [eə, øə, oə], which is reflected in how they are spelled in the local orthography: ⟨ee⟩, ⟨eu⟩ and ⟨oo⟩. Before nasals, the first two are monophthongized to [eː] and [ɵː].[16] Elsewhere in the article, their diphthongal nature is ignored.

- Among the unrounded front vowels, /e̞(ː)/ and /ɛ(ː)/ are retracted like /aː/, being near-front [e̽(ː), ɛ̠(ː)].[13]

- Apart from the phonetically central /ʏ/, the phonemic front rounded vowels are phonetically front, including the onset of /øː/: [y(ː), øə, œ̝(ː)].[13]

- Among the back vowels, /u(ː)/ and the onset of /oː/ are advanced like /ɑ(ː)/: [u̟(ː), o̟ə].[13]

- /e̞ː/ and /œː/ are less open than in other dialects, being true-mid [e̞ː, œ̝ː].[13] In other dialects, they tend to be open-mid [ɛː, œː]. This raising of the historical [ɛː] does not result in a merger with /eː/ (unlike in Maastrichtian), due to the centering glide found in the latter. Neither does /œː/ merge with /øː/, for the same reason. The back /ɔː/ is more open than /e̞ː/ and /œː/, making it similar to the corresponding cardinal vowel [ɔ]. The corresponding short vowels have the same quality: [e̞, œ̝, ɔ].[13]

- The closing diphthongs /ɛɪ, œʏ, ʌʊ/ are similar in quality to their Standard Dutch counterparts. Their ending points are more open than in Maastrichtian, in which especially /ɛɪ/ and /ʌʊ/ end in fully close glides [j] and [w] when they are combined with Accent 1, in addition to the rounded starting point of /ʌʊ/: [ɛj, ɔw] (the ending point of /œʏ/ is also fully close: [ɞʉ]).[17][18]

Phonotactics

- /ə/ occurs only in unstressed syllables.[4]

- /eː, øː, oː/ are phonological long monophthongs despite their obvious diphthongal nature. That is because they can occur before /ʀ/, unlike any of the six phonological diphthongs and /i, y, u/.[13] However, at least /iə/ sometimes violates that rule, as it occurs in the name of the town itself (/ˈwiəʀt/) and derivatives.

- /ɪ, ʏ, e̞/ are rare before /ʀ/.[13]

- Among the long open(-mid) vowels, /ɛː/ and /ɑː/ appear only before sonorants, making them checked vowels. They directly correspond to the short checked vowels /æ, ɑ/ combined with Accent 2 in other dialects (in which /æ/ corresponds to Weert /ɛ/). Thus, the phonological behavior of the long /ɛː/ and /ɑː/ is very different to that of /aː/, which is a free vowel like the other long vowels.[9]

- The closing diphthongs /ɛɪ, œʏ, ʌʊ/ are rare in the word-final position.[17]

Differences in transcription

Sources differ in the way they transcribe the unrounded front vowels of the Weert dialect in words such as zegke 'to say', blaetje 'leaf' (dim.), slét 'dishcloth' and tênt 'tent'. The differences are listed below.

| IPA symbols | Example words | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| This article | Heijmans & Gussenhoven 1998[16] | Ladefoged 2007[19] | ||

| i | i | i | Riet | |

| iː | iː | — | wiêt | |

| ɪ | ɪ | ɪ | hitst | |

| eː | eː | — | reet | |

| e̞ | ɛ | e | zegke | |

| e̞ː | ɛː | — | blaetje | |

| ɛ | æ | ɛ | slét | |

| ɛː | æː | — | tênt | |

| aː | aː | a | naat | |

This means that the symbols ⟨ɛ⟩ and ⟨ɛː⟩ have the opposite values, depending on the system. In this article, they stand for the vowels in words such as slét /ˈslɛt/ and tênt /ˈtɛːnt/. However, Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998) use them for the vowels in zegke /ˈze̞ɡə/ and blaetje /ˈble̞ːtʃə/, whereas slét and tênt are written with ⟨æ⟩ and ⟨æː⟩, respectively. In IPA transcriptions of Limburgish, the usual symbols employed for such words are ⟨ɛ(ː)⟩ and ⟨æ(ː)⟩. In this article, a phonetically explicit transcription ⟨e̞(ː), ɛ(ː)⟩ is used, not least because ⟨ɛ(ː)⟩ are as close as /ɔ(ː)/ in Weert. This transcription closely follows the symbols chosen by Ladefoged (2007), though he does not use the lowering diacritic for the vowels in zegke and blaetje. Furthermore, the phonetic open front vowel of Weert is /aː/, which is as front as /e̞(ː)/ and /ɛ(ː)/.

The closing diphthongs are given a phonetically explicit transcription ⟨ɛɪ, œʏ, ʌʊ⟩ in this article to match the changes described above. This kind of transcription has been used by e.g. Peters (2010) for vowels found in a transitional Brabantian-Limburgish dialect of Orsmaal-Gussenhoven.

Vowel+glide sequences

The Weert dialect allows a massive amount of vowel+glide sequences. Both short and long vowels can precede /j/ and /w/; in addition to that, the combinations with short vowels can be followed by a tautosyllabic consonant. There are five times as many possible combinations of a vowel followed by /j/ than the possible combination of a vowel+/w/: 15 in the former case (/ɪj, ʏj, œj, ɔj, ɛj, ɑj, yːj, uːj, eːj, øːj, oːj, e̞ːj, œːj, ɔːj, aːj/) and just 3 in the latter case (/ɔw, ɑw, oːw/). Out of those, both /ɔj/ and /ɑj/ are marginal.[17]

The sequences /ɛj/, /œj/ and /ɑw/ contrast with the phonemic diphthongs /ɛɪ, œʏ, ʌʊ/. The former begin with more open vowels than the phonemic diphthongs: [æj, ɶj, ɑw]. As stated above, the ending points of the phonemic diphthongs are lower than the glides /j/ and /w/: [ɛɪ, œʏ, ʌʊ], similarly to the diphthongs found in Standard Dutch, though they do not undergo monophthongization to [ɛː, œː, ʌː], unlike the corresponding sounds in Maastrichtian (whenever they are combined with Accent 2). In addition, /ɛɪ, œʏ, ʌʊ/ are all longer than /ɛj, œj, ɑw/. Thus, what in tonal dialects of Limburgish is the contrast between bein /ˈbɛɪn/ 'legs' (pronounced with Accent 1) and beîn /ˈbɛɪn˦/ 'leg' (pronounced with Accent 2) is a length and vowel quality difference in Weert: [ˈbæjn] vs. [ˈbɛɪn]. Other (near-)minimal pairs include Duits [ˈdɶjts] 'German' (adj.) vs. kuît [ˈkœʏt] 'fun' and oug [ˈɑwx] 'eye' vs. oûch [ˈʌʊx] 'also'.[20] This kind of contrast between a vowel+glide sequence and a diphthong is extremely rare in the world's languages.[21]

Suprasegmentals

The Weert dialect features an intonation system that is very similar to Standard Dutch. The stress pattern is the same as in the standard language. It does not feature a contrastive pitch accent, instead, the difference between Accent 1 and Accent 2 found in the more easterly dialects of Limburgish corresponds to a vowel length distinction in Weert; compare knien /ˈknin/ 'rabbits' and bérg /ˈbɛʀx/ 'mountains' with kniên /ˈkniːn/ 'rabbit' and bêrg /ˈbɛːʀx/ 'mountain'. The phonological vowel+glide sequences /ɛj, œj, ɑw/ correspond to /ɛɪ, œʏ, ʌʊ/ combined with Accent 1 in other dialects, whereas the phonological diphthongs /ɛɪ, œʏ, ʌʊ/ (which are longer than the vowel+glide sequences) correspond to /ɛɪ, œʏ, ʌʊ/ combined with Accent 2 in other dialects.[20]

According to Linda Heijmans, Weert dialect may have never been tonal at all, and the use of contrastive vowel length in minimal pairs such as knien–kniên could have sprung from the desire to sound like speakers of tonal dialects spoken nearby Weert, such as the dialect of Baexem.[22] This hypothesis has been rejected by Jo Verhoeven, who found that Weert speakers can still distinguish between the former tonal pairs on the basis of tone whenever vowel length is ambiguous. Thus, his findings support the theory that the former tone distinction was at some point reinterpreted as a vowel length distinction.[23]

Sample

The sample text is a reading of the first sentence of The North Wind and the Sun.

Phonetic transcription

[də ˈnoːʀdəweːntʃ ɛn də ˈzɔn | ˈɦaːjə nən dɪsˈkʏsi | ˈoːvəʀ də ˈvʀɔːx | ˈweːm vɑn ɦʏn ˈtwiːjə də ˈstɛːʀkstə woːʀ | tun dəʀ ˈjyst eːməs vəʀˈbeːj kwoːm | de̞ː ənə ˈdɪkə | ˈwɛːʀmə ˈjɑs ˈaːnɦaːj][24]

Orthographic version

De noordewîndj én de zon haje nen discussie over de vraog weem van hun twiêje de stêrkste woor, toen der juust emes verbeej kwoom dae ene dikke, wêrme jas aanhaaj.

References

- Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998), p. 107.

- Van der Looij (2017), p. 8.

- Van der Looij (2017), p. 50.

- Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998), p. 108.

- Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998), pp. 107–108.

- Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998), pp. 107, 110.

- Gussenhoven (2007), pp. 336–337.

- Ladefoged & Ferrari Disner (2012), p. 178.

- Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998), pp. 108–111.

- Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998), pp. 107, 109–110.

- Ladefoged (2007), pp. 162, 166.

- Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998), pp. 108–109.

- Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998), p. 109.

- Van der Looij (2017), pp. 8–9, 24, 34.

- Gussenhoven (2007), p. 339.

- Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998), pp. 109–110.

- Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998), p. 110.

- Gussenhoven & Aarts (1999), pp. 161–162.

- Ladefoged (2007), p. 162.

- Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998), pp. 110–111.

- Heijmans (2003), p. 16.

- Heijmans (2003), p. 34.

- Verhoeven (2008), p. 40.

- Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998), p. 112.

Bibliography

- Gussenhoven, Carlos (2007). "Wat is de beste transcriptie voor het Nederlands?" (PDF) (in Dutch). Nijmegen: Radboud University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- Gussenhoven, Carlos; Aarts, Flor (1999). "The dialect of Maastricht" (PDF). Journal of the International Phonetic Association. University of Nijmegen, Centre for Language Studies. 29 (2): 155–166. doi:10.1017/S0025100300006526. S2CID 145782045.

- Heijmans, Linda (2003). "The relationship between tone and vowel length in two neighboring Dutch Limburgian dialects". In Fikkert, Paula; Jacobs, Haike (eds.). Development in Prosodic Systems. Studies in Generative Grammar. Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 7–45. ISBN 3-11-016684-4.

- Heijmans, Linda; Gussenhoven, Carlos (1998). "The Dutch dialect of Weert" (PDF). Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 28 (1–2): 107–112. doi:10.1017/S0025100300006307. S2CID 145635698.

- Ladefoged, Peter (2007). "Articulatory Features for Describing Lexical Distinctions". Language. Linguistic Society of America. 83 (1): 161–180. doi:10.1353/lan.2007.0026. JSTOR 4490340. S2CID 145360806.

- Ladefoged, Peter; Ferrari Disner, Sandra (2012) [First published 2001]. Vowels and Consonants (3rd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-3429-6.

- Peters, Jörg (2010). "The Flemish–Brabant dialect of Orsmaal–Gussenhoven". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 40 (2): 239–246. doi:10.1017/S0025100310000083.

- Van der Looij, Dion (2017). The dialect of Weert: use, appreciation and variation within the dialect (Thesis). Nijmegen: Radboud Universiteit.

- Verhoeven, Jo (2008). "Perceptie van toon en vocaalduur in het dialect van Weert: toonverschillen als indicatie van voormalige polytonie". Handelingen - Koninklijke Zuid-Nederlandse maatschappij voor taal- en letterkunde en geschiedenis (in Dutch). 62: 29–40. doi:10.21825/kzm.v62i0.17436.