Watts' West Indies and Virginia expedition

Watts' West Indies and Virginia expedition also known as the Action of Cape Tiburon[6] was an English expedition to the Spanish Main during the Anglo–Spanish War.[5][8] The expedition began on 10 May and ended by 18 July 1590 and was commanded by Abraham Cocke and Christopher Newport. This was financed by the highly renowned London merchant John Watts.[9] The English ships intercepted and dispersed Spanish convoys capturing, sinking, and grounding many ships off the Spanish colonies of Hispaniola, Cuba, and Jamaica.[1] Despite losing an arm, Newport was victorious and captured a good haul of booty.[10] A breakaway expedition from this discovered that the Roanoke Colony was completely deserted and which gave the name The Lost Colony.[11]

| Watts' West Indies and Virginia expedition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo–Spanish War | |||||||

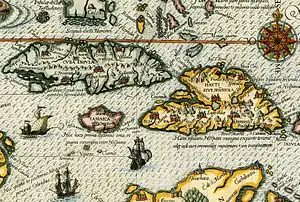

Map of the Caribbean in 1594 by Theodor de Bry - the expedition took place in Cuba, Jamaica, & Hispaniola | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Rodrigo de Rada Vicente González |

Christopher Newport Abraham Cocke | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 17 ships |

6 ships 400 men[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1 galleon captured[5] 1 galleon sunk, 4 ships captured, 3 ships run aground[6] | 60 casualties[7] | ||||||

Background

By the end of 1589 the immediate threat of a Spanish invasion of England had been abated. Attempts were now made by privateering expeditions or joint-stock companies to raid the Spanish Main. In the Spring of 1590 a privateering expedition had been raised and financed in London by merchant John Watts. Watts gathered a naval force with a mixture of armed merchants ships and naval vessels loaned by the English crown.[12] The force composed of the 22-gun, 160-ton flagship Hopewell (alias Harry and John) under Captain Abraham Cocke; the 160-ton Little John of Christopher Newport, and the 35-ton pinnace John Evangelist of William Lane (brother of Ralph Lane).[13]

Their objective was to raid the Spanish West Indies and to coup the rewards of the expedition, but also on the return voyage to help the Roanoke colonists. With them was John White, an artist and friend of Sir Walter Raleigh who had accompanied the previous expeditions to Roanoke. Raleigh had helped put together the fleet along with the aid of White himself who was desperate to go back to Roanoke and help the colonists.[12] As a result, two ships, the Hopewell and the Moonlight were intended as a break off expedition to set sail for Roanoke.[14]

Expedition

On 20 March the English set sail from Plymouth and crossed the Atlantic without hindrance and reached the island of Dominica by 10 May.[3] They replenished for victuals and two days later the Hopewell and John Evangelist had steered Northwest towards Puerto Rico, whilst leaving Little John temporarily off Dominica to intercept arriving Spanish vessels. All three later rendezvoused at Saona Island.[15]

Santo Domingo

On 29 May off the south coast of Hispaniola, Abraham Cocke's formation of three ships were joined by Edward Spicer's 80-ton Moonlight (alias Mary Terlanye) and the 30-ton pinnace Conclude of Joseph Harris in the morning. Cocke's reunited trio of vessels then blockaded the southern coast of Santo Domingo for two weeks, capturing the 60-ton Spanish merchantman Trinidad and two smaller island frigates on 17 and 24 June respectively.[6] After these captures the English broke off the blockade and moved further West towards the Tiburon peninsula of Hispaniola.[3]

Tiburon to Colony of Santiago

On 12 July whilst off the Tiburon, fourteen Spanish sail approached out of the east.[13] These ships were five days out of Santo Domingo and were bound toward the Spanish plate fleet assembly point at Havana escorted by Captain Vicente González's galleon. The English ships took up position to pursue and were just in time as Newport's Little John and John Evangelist came up to join them.[15]

Cocke gave an immediate signal to attack; the Spanish who saw the English approach decided to scatter, and the armed ships attempted to form a defensive position to allow the lighter armed vessels to escape.[13] Suddenly on seeing Newport's ships come from behind Cocke's vessels, Gonzalez decided to retreat.[6] Most of the Spanish convoy decided to scatter south west and they were pursued until nightfall by the six privateers, who took a single prize, a pinnace.[1]

The following morning, Hopewell, Moonlight, and Conclude then discovered the 350-ton, nine-gun Spanish vice flagship galleon Buen Jesús of Captain Manuel Fernández Correa and Master Leonardo Doria anchored nearby. Cocke then attacked surprising the Spanish; with the Buen Jesús unable to get away in the process of hauling its anchor a long range exchange of fire commenced in which six Spanish were killed and four wounded.[6] The English then closed amidships firing as they came alongside but as they attempted to board the vessel they were repelled.[13] Undeterred the English made a more determined attack and secured it despite a stout, four-hour resistance, most of which consisted of hand-to-hand fighting.[15] As well as the ship being captured, sixty eight Spaniards were captured with another twenty killed or wounded while English losses were around fifteen.[16]

Whilst the fight for Buen Jesus was going on Little John and John Evangelist chased González's main body which was headed South West toward the Colony of Santiago (present-day Jamaica) and all the while exchanged broadsides with the Spanish flagship.[17] As soon as the Spanish arrived off Caguaya bay the English ships immediately drove at two of them.[18] With intense fire the English were able to force the two ships aground before the six or seven Spanish vessels that survived reached Santiago de la Vega.[1] English boat parties then immediately attacked the grounded ships; the Spanish that did defend them were easily driven off.[15] An attempt to refloat both beached vessels then began as they used ropes and a helpful southerly wind.[3] The English managed to get one of the ships off the beach but the attempt was not successful with the other ship - already badly damaged it then sank.[6] The English then re-embarked their ships and together with the new prize sailed Northwest toward Cape Corrientes.[17]

On 14 July Cocke gave the Buen Jesus to Newport for protection since her cargo was immense and needed to be transported back to England with haste. The cannons and firearms from the ship were stripped off before Newport's victorious privateers withdrew from the Jamaican coastline and headed East towards Cuba.[16]

Cayo Jutias

.jpg.webp)

At sunset on 18 July, Newport's Little John and John Evangelist sighted three Spanish merchantmen off Cayo Jutias (west of Havana and north of Los Órganos).[15] They proved to be stragglers from Commodore Rodrigo de Rada's convoy from Veracruz, which had entered the Cuban capital five days earlier.[17] The English attacked in the darkness and opened fire compelling one ship to reverse course. The following morning the English closed in on the remaining pair: the 150-ton Nuestra Señora del Rosario captained by Miguel de Acosta and a 60-ton pinnace Nuestra Señora de la Victoria under Juan de Borda.[7] The Spaniards had lashed both vessels together, and a long-range artillery exchange commenced which the English got the better of, severely damaging Victoria.[3] The English then closed amidships with the Victoria and managed to board her and ferocious hand-to-hand combat soon followed.[5] Newport killed the Spanish captain in the melee that followed but soon after his right arm was struck off by another Spaniard trying to protect his captain.[6] However Newport was saved by a sergeant-at-arms who killed his would be assailant.[15] The Spanish were soon driven from the vessel and the English suffered five killed and sixteen wounded (including Newport) while the Spanish losses were higher.[16]

The English then discovered Victoria to be so badly holed that it sank within fifteen minutes, taking much of the silver within.[9] The next target, the Spanish vessel Rosario, was swiftly boarded not long after.[10] Another vicious fight took place but again the English soon forced the Spanish from the vessel having suffered two killed and eight injured.[3] The Rosario too was badly damaged and sinking; the English had no choice and drove the vessel ashore at the western end of Cayo Jutias.[7] Soon after Newport despite being in pain and shock still sent orders and released the Spanish prisoners and sent them ashore.[6] The English then pillaged the vessel but found only a small haul of valuables after which was then broken up and burnt.[18] Newport with only half his arm ordered a return to England.[16]

Newport sailed back to England leaving Cocke in charge, so the Hopewell and the Moonlight with John White sailed to Roanoke with their half of the mission complete.[19][11]

Expedition to Roanoke

Meanwhile, the other half of the expedition sought to land at the English colony of Roanoke. White's eventual landing at the Outer Banks was further imperilled by poor weather and the landing was hazardous and was beset by bad conditions and adverse currents.[16]

On August 18, 1590 he finally reached Roanoke Island, but he found his colony had been long deserted. The few clues about the colonists whereabouts included the letters "CRO" carved into a tree, and the word "CROATOAN" carved on a post of the fort. Croatoan was the name of a nearby island (modern-day Hatteras Island) and a local tribe of Native Americans.[11] The colonists had agreed that a message would be carved into a tree if they had moved and would include an image of a Maltese Cross if the decision was made by force. With no sign of the colonists and the weather becoming worse White returned to Plymouth on October 24, 1590.[20]

Aftermath

Newport returned home to a hero's welcome by early September and counted the large spoils of which was a profitable expedition.[1] The biggest and most profitable was the 300-ton Buen Jesus which sailed into Plymouth in September - the prize had been from Seville, and was typical of Spanish trade at the time. On board: 200 boxes of sugar, at least 5,000 hides, 2,000 hundredweight of ginger, 400 hundredweight of guacayan wood, twelve hogsheads of Chile pepper, twenty hundredweight of sarsaparilla, twenty hundredweight of cane, and over 4,000 ducats in pearls, gold, and silver.[16]

The English expedition and the defeat of the convoys proved frustrating to the Spanish. Their commander Rodrigo de Rada wrote afterwards:

the shamelessness of these English ships has reached a point they have come very close to this harbour [Havana] even pursuing barges which bring water from a league away.[9]

Addicted to the prize hunting, Newport set out again, despite the loss of his arm - he owed his life to the ship's surgeon.[19] The following year as captain of the Margaret he combined Barbary trade with Watt's most successfully financed expeditions; the Blockade of Western Cuba. Between 1592 and 1595, when captaining the Golden Dragon, Newport kept to the West Indies again. In 1592 he was given command of a flotilla of privateers and he pioneered attacks on the towns of the Spanish Caribbean. On his return he helped to capture the Madre de Deus off the Azores and was chosen to sail her to England, making him a very rich man.[21]

Legacy

Newport would be shown erroneously with an arm (played by Christopher Plummer) in Terrence Malick's film of the Jamestown Settlement New World and his statue at Christopher Newport University of which is named after him.[10]

References

- Citations

- Bradley pp 104-05

- Nichols p 33

- Loker pp 111-112

- The Roanoke voyages, 1584-1590: documents to illustrate the English voyages to North America under the patent granted to Walter Raleigh in 1584, Volume 104, Part 2. Hakluyt Society. 1955. p. 69.

- Andrews p 87

- Marely (2008) pp 77-78

- Nichols pp 24-28

- Appleby p 189

- Andrews p 164-65

- Bicheno p 316

- Milton pp 261-65

- Aronson p. 105

- The Roanoke voyages, 1584-1590: documents to illustrate the English voyages to North America under the patent granted to Walter Raleigh in 1584, Volume 104, Part 2. Hakluyt Society. 1955. pp. 584–590.

- Milton pp 257-58

- Milton pp 259-60

- Hakluyt Society, pp 592-603

- Marley (2005) p 150

- Southey p 210

- Nichols pp 29-33

- Milton pp 266-68

- Bicheno 2012, p. 304–06.

Bibliography

- Andrews, Kenneth R (1964). Elizabethan Privateering 1583-1603. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521040327.

- Appleby, John (2011). Under the Bloody Flag: Pirates of the Tudor Age. The History Press. ISBN 9780752475868.

- Aronson, Marc (2000). Sir Walter Ralegh and the Quest for El Dorado. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780395848272.

- Bicheno, Hugh (2012). Elizabeth's Sea Dogs: How England's Mariners Became the Scourge of the Seas. Conway. ISBN 978-1844861743.

- Bradley, Peter T (2010). British Maritime Enterprise in the New World: From the Late Fifteenth to the Mid-eighteenth Century. Edwin Mellen Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0773478664.

- Dean, James Seay (2013). Tropics Bound: Elizabeth's Seadogs on the Spanish Main. The History Press. ISBN 9780752496689.

- Loker, Aleck (2006). Walter Ralegh's Virginia. Solitude Press. ISBN 978-1928874089.

- Marley, David (2005). Historic Cities of the Americas: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1576070271.

- Marley, David (2008). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the Western Hemisphere. ABC CLIO. ISBN 978-1598841008.

- Milton, Giles (2000). Big Chief Elizabeth - How England's Adventurers Gambled and Won the New World. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0340748824.

- Nichols, Allen Bryant (2007). Captain Christopher Newport: Admiral of Virginia. Sea Venture LLC. ISBN 978-0615140018.

- Southey, C.T (2013). Chronicle History of the West Indies. Routledge. ISBN 9781136990663.

- External links