Vidor, Texas

Vidor (/ˈvaɪdər/ VY-dər) is a city in western Orange County, Texas, United States. A city of Southeast Texas, it lies at the intersection of Interstate 10 and Farm to Market Road 105, 6 miles (9.7 km) east of Beaumont. The town is mainly a bedroom community for the nearby refining complexes in Beaumont and Port Arthur and is part of the Beaumont-Port Arthur metropolitan statistical area. Its population was 9,789 at the 2020 census.

Vidor, Texas | |

|---|---|

City Hall | |

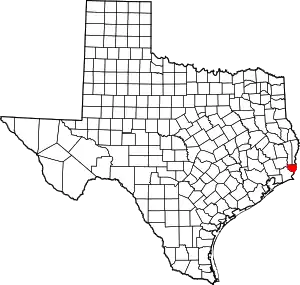

Location of Vidor, Texas | |

| |

| Coordinates: 30°7′53″N 93°59′47″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| County | Orange |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • City Council | Mayor Misty Songe Mercedes Lee (I) Nicole McGowan (II) Michael Thompson (III) Jessica Barker (IV) Gary Herrera (V) Kathryn Weldon (VI) |

| • City Manager | Robbie Hood |

| Area | |

| • Total | 12.12 sq mi (31.39 km2) |

| • Land | 12.02 sq mi (31.12 km2) |

| • Water | 0.10 sq mi (0.27 km2) |

| Elevation | 23 ft (7 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 9,789 |

| • Density | 865.83/sq mi (334.29/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 77662, 77670 |

| Area code | 409 |

| FIPS code | 48-75476[2] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1349270[3] |

| Website | cityofvidor |

The area was heavily logged after the construction of the Texarkana and Fort Smith Railway that was later part of a line that ran from Kansas City to Port Arthur, Texas. The city was named after lumberman Charles Shelton Vidor, owner of the Miller-Vidor Lumber Company and father of director King Vidor. By 1909, the Vidor community had a post office and four years later a company tram road was built. Almost all Vidor residents worked for the company. In 1924, the Miller-Vidor Lumber Company moved to Lakeview, just north of Vidor, in search of virgin timber. A small settlement remained and the Miller-Vidor subdivision was laid out in 1929.

Vidor had and still has a reputation as a "sundown town", where African Americans are not allowed after sunset. [4][5] In 1993, after district court judge William Wayne Justice ordered that 36 counties in East Texas, including Vidor, desegregate public housing by making some units available for minorities, the Klan held a march in the community after a long legal battle was lost by Vidor's leaders. Church leaders held a well-attended prayer rally in opposition to the KKK hatred.[6][7][8] After four Black families moved into the complex, the residents suffered racial threats including a bomb threat to the complex. All nine Black residents eventually moved out under this pressure.[9] One of the residents, Bill Simpson, was interviewed about his negative experiences while living there. "I've had people who drive by and tell me they're going home to get a rope and come back and hang me. . . ."[9] During the George Floyd protests of 2020, Black Lives Matter held a rally in Vidor that was attended by a diverse crowd of 150–200 people.[4][10]

In 2005, 2008, and 2017, Vidor and surrounding areas suffered extensive damage from Hurricanes Rita, Ike, and Harvey. A mandatory evacuation was imposed upon its residents for about two weeks.

Geography

Vidor is located at 30°7′53″N 93°59′47″W (30.131492, –93.996292).[11]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 10.6 square miles (27 km2), of which, 10.6 square miles (27 km2) are land and 0.09% is covered by water.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 9,738 | — | |

| 1980 | 11,834 | 21.5% | |

| 1990 | 10,935 | −7.6% | |

| 2000 | 11,440 | 4.6% | |

| 2010 | 10,579 | −7.5% | |

| 2020 | 9,789 | −7.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] | |||

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 8,671 | 88.58% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 39 | 0.4% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 47 | 0.48% |

| Asian (NH) | 50 | 0.51% |

| Some Other Race (NH) | 11 | 0.11% |

| Mixed/Multi-Racial (NH) | 294 | 3.0% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 677 | 6.92% |

| Total | 9,789 |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 9,789 people, 4,129 households, and 2,639 families residing in the city.

As of the census[2] of 2000, 11,440 people, 4,222 households, and 3,158 families were residing in the city. The population density was 1,083.6 inhabitants per square mile (418.4/km2). The 4,652 housing units averaged 440.6 per square mile (170.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 97.3% White, 0.1% African American, 0.5% Native American, 0.2% Asian, 0.73% from other races, and 1.21% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 3.49% of the population.

Of the 4,222 households, 34.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 56.3% were married couples living together, 13.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 25.2% were not families. About 22.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.66, and the average family size was 3.09.

In the city, the population distribution was 26.7% under the age of 18, 9.9% from 18 to 24, 27.4% from 25 to 44, 21.9% from 45 to 64, and 14.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.1 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $31,982, and for a family was $37,572. Males had a median income of $35,781 versus $21,054 for females. The per capita income for the city was $15,381. About 10.7% of families and 14.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 19.5% of those under age 18 and 8.9% of those age 65 or over.

Education

The City of Vidor is served by the Vidor Independent School District, which is the largest of the six school districts in the county.

Notable people

- Tracy Byrd, country music artist

- Dean Corll, prolific 1970s Houston serial killer

- David Ray Harris, suspected murderer featured in the documentary The Thin Blue Line (and later executed for a separate murder)

- Tamara Hext, 1984 Miss Texas

- John Hirasaki, NASA mechanical engineer

- Roger Mobley, former child actor, was a police detective in Vidor

- David Ozio, Professional Bowlers Association and USBC Hall of Famer

- Don Rollins, songwriter, co-author of "It's Five O'Clock Somewhere"

- Billie Jo Spears, country music artist

- Clay Walker, country music artist

Notes

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- Hooks, Christopher (June 6, 2020). "Black Lives Matter Comes to Vidor – Yes, Vidor". Texas Monthly. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- Loewen, James William (1942–2021) (2005). Sundown Towns – A Hidden Dimension of American Racism (hardcover ed.). New York: The New Press. pp. 7, 212, 276, 348, 444. ISBN 1-5658-4887-X. LCCN 2005043855. OCLC 61441130.

- Via Google Books (limited review). 2005.

- Via Google Books (limited review). 2005.

-

- CNN; Oppenheim, Keith (December 13, 2006). "Texas City Haunted by 'No Blacks After Dark' Past". Retrieved January 6, 2019.

{{cite news}}:|last1=has generic name (help)One of the first African-American residents, Bill Simpson, was murdered soon after he arrived. - Baltimore Sun, The (September 3, 1993). "Black Flees Mean Town, Dies in Next Gentle Giant Victim of Robbers" (dateline: Houston → article, by J. Michael Kennedy, is from the Los Angeles Times–Washington Post News Service). Vol. 313, no. 95 (Final ed.). p. 1 (section A). Retrieved January 12, 2021. ProQuest 306458805 (US Newsstream database).

- Los Angeles Times, The; Kennedy, J. Michael (September 3, 1993). "'Gentle Giant' Escapes Klan Fear in Vain, Dies at Hands of Gang". National Desk (Dateline: Houston). Vol. 112, no. 274. Retrieved February 12, 2021. → ISSN 0458-3035 (publication) → (US Newsstream database) (article) → ProQuest 421150595 (US Newsstream database) (article) → Alternate link 1. p. 18 (section A). Alternate link 2 (Washington ed.). p. 5 (section A) – via Newspapers.com..

- Washington Post, The; Sue Anne Pressley Montes (September 3, 1993). "A New Residence and a Tradegy – Forced Out of One Texas Town, Black Man Is Killed on Street". p. 4 (section A). Retrieved June 8, 2020. ProQuest 307675622 (US Newsstream); ProQuest 408163601 (US Newsstream).

- The Independent; Hall, Richard (June 18, 2020). "Vidor Was Known for Its KKK Past – Then Black Lives Matter Came to Town". Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- https://www.census.gov/

- "About the Hispanic Population and its Origin". www.census.gov. Retrieved May 18, 2022.