Victoria College, Jersey

Victoria College is a Government-run, fee-paying, academically selective day school[7] for boys in St Helier, Jersey. Founded in 1852, the school is named after Queen Victoria. It is owned and administered by the Government of Jersey and is located on Mont Millais adjacent to Jersey College for Girls, the Government fee-paying secondary school for girls.[7][8][5] As a fee-charging school and a member of the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference (HMC), Victoria College is often considered a private school or a public school in the British sense of the term, despite receiving government funding.[9][10]

| Victoria College | |

|---|---|

| |

| Address | |

Le Mont Millais , JE1 4HT Jersey | |

| Coordinates | 49.1856°N 2.0966°W |

| Information | |

| Type | Government fee-paying selective school |

| Motto | Latin: Amat Victoria Curam (Victory favours preparation) |

| Religious affiliation(s) | Christian; non-denominational[1] |

| Established | 1852 |

| Local authority | Government of Jersey |

| Chair of governors | Richard Stevens[2] |

| Headteacher | Gareth Hughes[3] |

| Staff | 80+[4] |

| Gender | Boys |

| Age range | 7 to 18[5] |

| Enrolment | 664 (2017)[5] |

| Houses |

|

| Colour(s) | Black and yellow |

| Song | Carmen Caesariense |

| Rival | Elizabeth College, Guernsey |

| Publication | The Victorian |

| School fees | £2,240 per term (2021/2022)[6] |

| Affiliation | Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference |

| Alumni | Old Victorians |

| Visitor | Charles III |

| Website | www |

The school's main building | |

The school is selective, meaning prospective pupils must pass an entrance exam to be offered a place. The school charges £2,240 per term, with three terms per academic year, as of 2021/2022, and was noted as being the seventh-least expensive day school in the HMC in 2014.[11] The senior school has about 650 boys aged 11 to 18, with a further 250 boys aged 7 to 11 at the associated preparatory school, which was established in 1966.

History

Foundation

The foundation stone of the school was laid on Queen Victoria's birthday, 24 May 1850. Most shops in Saint Helier closed for the day and 12,000 spectators were estimated to have attended the occasion. A military parade crossed the town of Saint Helier to the site of the ceremony, followed shortly afterwards by the members of the States of Jersey who adjourned the legislative sitting to attend. The Lieutenant-Governor of Jersey joined the dignitaries at the Temple in the grounds of the site. The Bailiff of Jersey laid in the foundations a box containing copies of the Acts of the States relating to the college, Jersey coins, and two medallions, one of silver, the other of bronze, depicting the arrival of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in Jersey in 1846, and a copper plate engraved with an inscription of the date of the founding of the college and the names of States Members, Officers of the Royal Court and the architect. With the foundation stone, carved with Masonic symbols, in place, the Lieutenant-Governor ceremonially laid the stone by striking it with a trowel. All the Members of the States in turn then proceeded to tap the stone with a mallet three times.[12]

The school was opened on 29 September 1852 with 98 students enrolled.[13] The accompanying ceremony featured a military parade, and the Lieutenant-Governor and the States of Jersey again assembled in the Temple and processed to the Great Hall where the Bailiff addressed the audience. He recalled the royal visit of 1846 and stated that the intention of memorialising that visit had inspired the construction of a college for the instruction of youth and of promenades for the recreation of the public. He stated that the interest shown by the Queen and the Prince in the college had led them to present two portraits. The Lieutenant-Governor then formally presented the portraits of the royal couple. The quality of the portraits, copies of Winterhalter, was criticised in the press.[14] The initial uniform consisted of a jacket, waistcoat and trousers in black or dark green, and a cap of the same colour.[13] The establishment of the College represented the triumph for those who wished to anglicise Jersey.[15]: 589

World war period

By the end of the 19th century, the school had gained a reputation for producing students who would go on to study at military academies in the United Kingdom, including Woolwich and Sandhurst, or take up direct appointments in the military, naval and civil service of the armed forces. At a time when the British Empire was at its height, this reputation came as no surprise, with many students' fathers being former officers and colonial administrators, and with there being a strong military influence in the island at the time. Within the first twenty-five years of the institution of the Victoria Cross in 1856, three Old Victorians were awarded the honour for their services, with two further alumni receiving the award for their service during World War I.[16]

In early 1940 the school remained largely unaffected by the outbreak of war in Europe, and although many young Jerseymen had left the island to join the war effort, several English parents had sent their sons to board at the school, believing the Channel Islands to be the safest place in the British Isles. However, developments in the war throughout May that year and the eventual collapse of French resistance meant it became clear the island was in danger. The Channel Islands were demilitarised in the belief that this would best protect the lives of the islanders, meaning many feared the imminent occupation of the islands by German forces. While many other schools in Jersey left evacuation decisions in the hands of parents, Victoria College decided to evacuate some boys and their masters to the UK where they stayed for the remainder of World War II attending English public schools, including Shrewsbury and Bedford.[17][18] However, around 130 boys and several masters remained in Jersey,[17] and the school continued to operate during the occupation.[19]

Early on during the occupation, the German forces commandeered College House building for the Reich Labour Service,[20][21] but otherwise did not significantly disrupt the normal routine of the school for much of 1941. However, in September that year, German forces took possession of the remaining school buildings, forcing the students and masters to relocate to Halkett Place school. Around a year later, another blow was dealt to the school as several English-born masters and staff were deported to Germany, though substitutes were found and the school remained open. Soon thereafter, however, in October 1942 the German forces returned the buildings to the school. Only minimal damage had been done to the buildings, with the hall windows partially painted black, and by 1943 the school had restored the building to its original state. Life in Jersey became increasingly worse for the remainder of the occupation, as there was no gas nor electricity and food supplies were increasingly scarce. As a result, afternoon schooling was discontinued, homework not issued, and sports were only played on a small scale. British food-parcels arrived early in 1945, relieving some of the hardship suffered by islanders, and eventually on 8 May 1945 the headmaster relayed news of Victory in Europe and all 175 boys were dismissed to join the celebrations.[17]

Modern period

A memorial service was held on 2 June 1946 in the main hall to remember Old Victorians who died in the war. The school quickly returned to its normal functioning, and the next few years saw a range of developments including a wider range of subjects and the building of a new sports pavilion and art building. By 1952, the school was in a state fit to celebrate its centenary, which was marked by a visit from the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester.[17] This development continued into the next decade as an associated preparatory school was opened in 1966.[5] The school's 125 year anniversary was commemorated by Jersey Post with an issue of special stamps on 29 September 1977.[22]

In the late 1990s, the school was involved in a highly publicised child abuse scandal concerning a maths teacher at the school, Andrew Jervis-Dykes, and the attempts by staff at the school to cover up the abuse. Allegations were made against Jervis-Dykes in 1992 and 1994, but on both occasions, the school's headmaster, Jack Hydes, failed to notify the police or investigate the allegations and instructed staff not to discuss the allegations.[23] In 1996, thirteen pupils alleged that Jervis-Dykes had abused them on a Navy Cadet sailing trip, but again the allegations were dismissed by the school as rumours. However, a video showing Jervis-Dykes assaulting several boys subsequently emerged and Jervis-Dykes was arrested by Jersey Police; headmaster Jack Hydes and his deputy, Piers Baker, refused to engage in the investigation or identify the boys in the video.[24] Eventually, in April 1999, Jervis-Dykes was sentenced and jailed for six counts of indecent assault against six school pupils whom he had given alcohol to before abusing them in their beds on school sailing trips between 1984 and 1993 and one count of possession of an indecent photograph of a child.[23][25]

The Sharp Report, instigated as a result of the investigation into Jervis-Dykes' actions and the actions of school staff,[26] noted that "The handling of the complaint was more consistent with protecting a member of staff and the college's reputation in the short-term than safeguarding the best interests of the pupil", continuing to say "The reaction of the political establishment was to sweep this under the carpet and keep the veneer of respectability ... This is just another example of concealment and cover up. They did the bare minimum, prosecuted one perpetrator."[27] Both Hydes and Baker subsequently resigned from the school.[23] In the Independent Jersey Care Inquiry, an inquiry investigating child abuse in Jersey launched in 2014, a member of the island's Child Protection Team said that many of his colleagues were alumni of the school and therefore did not offer any support to the investigation into Jervis-Dykes as they did not want the school's reputation "dragged through the mud."[28]

School structure

In the English public school tradition, the school operates on a house system.[29] There are five houses—Braithwaite, Bruce, Diarmid, Dunlop and Sartorius—named after alumni distinguished for their military service and each house has its own room. House flags are hung atop the east tower of the school's main building, each celebrating a variety of achievements of each house every month throughout the year.[4]

Teaching at the school is delivered over 25 periods a week divided into 60-minute lessons,[30] with a typical school day starting at 8:25 am and finishing at 3:25 pm.[31] Year groups are divided into five tutor groups of either 23 or 24 students divided by house, each overseen by a dedicated tutor.[4]

Governance

The school is owned by the States of Jersey and is governed by a board of governors made up of parent governors, invited governors selected "to reflect an appropriate balance of interests and to help provide links with the local community", and staff governors.[32][5]

All staff, including the school's head teacher, are employees of Jersey's Children, Young People, Education and Skills department. It is headed by a director general, to which all staff and the headteacher of the school directly report. Its role is supportive, providing advice and mediation practices, and to ensure accountability. The Government of Jersey’s human resources department controls the recruitment of staff and governors in conjunction with the school, making appropriate checks to ensure all are suitable.[5]

An inspection report by the Independent Schools Inspectorate (ISI) in 2017 found that "Governors provide suitable support and guidance for the college ... and they monitor the quality of procedures", noting also that "The Jersey Education Department and governors of the schools ensure that the leadership and management demonstrate good skills and knowledge, and fulfil their responsibilities effectively so that the other standards are consistently met and they actively promote the well-being of the pupils."[5]

As well as being fee-charging, the school is also a member of the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference (HMC).[10] As a result, the school is often referred to as a private school in the British sense of the term, despite being owned by the States of Jersey.[9]

Admissions

The senior school accepts pupils between the ages of 11 and 18, and its associated preparatory school accepts pupils between the ages of 7 and 11. The senior school is selective, meaning admission is based on ability which is assessed by way of an entrance examination. Pupils of the preparatory school, who make up around 75% of the senior school's intake, are not required to sit such an assessment and are admitted automatically.[33][5]

In 2017, the ISI inspection report found that pupils were admitted from across the island from families with a wide range of professional backgrounds and predominantly from white British families; around 40% of pupils were born in the United Kingdom.[5] As of 2021/2022, the school charges £2,240 per term with three terms per academic year.[6]

Curriculum

Structure

From years 7 to 9, the school curriculum follows the island's curriculum programme. Beyond year 9, the school designs its own curriculum to provide a more tailored framework for pupils which conforms to English National Curriculum requirements.[34][30] At GCSE level, in years 10 and 11, all students must take English, mathematics and physical education and they are expected to study a modern foreign language and religious studies, at least two sciences, and three optional subjects. At A-level, students will study three or four subjects over two years.[30][34] Almost all boys at the school go on to study at universities in the UK.[34] The school partially shares its teaching with the nearby Jersey College for Girls.[5]

An ISI report in 2017 noted that "The breadth of the curriculum, combined with ane extensive activity programme, provides pupils with experience in linguistic, mathematical, scientific, technological, human and social, physical, and aesthetic and creative education. Literacy, science and mathematics are emphasised with a particular focus on improving literacy standards" describing the curriculum as "well planned and timetabled with suitable schemes of work."[5]

Examinations

Students are entered for GCSE and IGCSE examinations in years 10 and 11 and A-level examinations in the sixth-form. A 2017 ISI report found that "The majority of pupils attain high standards in public examinations", finding that, for the period 2014 to 2016, GCSE results were consistently above the UK national average for maintained schools with nearly half of all papers graded A or A*, IGCSE results in biology and physics were higher than worldwide norms, and two-thirds of A-level results were graded A* to B.[5]

Extracurricular activities

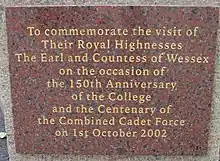

A wide range of extracurricular activities are offered at the school. Students participate in a range of sports, arts, music and local events, as well as the school's Combined Cadet Force (CCF). Students also participate in The Duke of Edinburgh's Award programme.[5] Regular contests in cricket, hockey and rifle shooting have been held against rivals Elizabeth College for over a century.[35][36][37]

An ISI report in 2017 found that the level of extracurricular achievement at the school was "excellent" and described the CCF as "a real strength of the school", noting in particular its success in target rifle shooting, where students regularly make selection for UK and British cadet teams.[5]

School site

The school occupies an extensive area on the hills above Saint Helier and facing the bay of Saint-Malo. The neo-gothic main building, finished in 1852, remains in use and houses the great hall, libraries and administrative areas.[34] Newer developments including classrooms, a music centre, science suite, design and technology suite, computer suites, theatre and sixth form centre surround the historic building.[34] The school shares some of its facilities with the Jersey College for Girls located on the adjacent site.[5]

The school owns or has access to a wide range of sporting facilities. Adjacent to the main buildings lie several playing fields, and the main site also includes a 25-yard shooting range and squash courts.[34] The school, along with the Jersey College for Girls, uses the Langford sports centre during term times, which provides a 25-metre swimming pool, dance studio, gymnasium and sports hall.[38]

The school's main building was described by David Ansted and Robert Latham as "a handsome building, well placed, overlooking the town on the eastern side, and from one direction is extremely picturesque" in their book, The Channel Islands, published in 1862.[39]

Notable alumni

The school's alumni are often referred to as Old Victorians. Notable alumni of the school in the military include five Victoria Cross holders, Henry William Pitcher,[40] William Bruce,[41] Allastair McReady-Diarmid,[42] and brothers Reginald and Euston Sartorius.[43]

Principals

The school's first headmaster was William Henderson. A graduate of Magdalen College, Oxford, Henderson was headmaster of the school for ten years from 1852 until 1862.[44] The school's current headmaster is Gareth Hughes, who took up the post in 2021 on a one-year basis following the retirement of Alun Watkins. The full list of headmasters of the school is as follows:[45]

19th century

- William Henderson (1852–1862)

- CJ Wood (1862–1863)

- WO Cleave (1863–1881)

- Robert Halley Chambers (1881–1892)

- George Stanley Farnell (1892–1895)

- Lester Vallis Lester-Garland (1896–1911)[46]

20th century

- AH Worral (1911–1933)

- GH Grummit (1933–1940)

- Percy Albert "Pat" Tatam (acting; 1940–1945)

- Ronald Postill (1946–1967)

- Martin Devenport (1967–1991)

- Brian Vibert (acting; 1991–1992)

- Jack Hydes (1992–1999)

- Philip Stevenson (acting; 1999–2000)

21st century

- Robert "Bob" Cook (2000–2010)[47]

- Alun Watkins (2010–2021)

- Gareth Hughes (2021–)

See also

References

- "Victoria College". isbi.com. isbi schools. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Meet Our Governors".

- "Our People and Community". Victoria College, Jersey.

- "Victoria College - School Life". victoriacollege.je. Victoria College. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- "Victoria College: Independent Schools Inspectorate". isi.net. Independent Schools Inspectorate (ISI). November 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Victoria College - For Parents". victoriacollege.je. Victoria College. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- Education Journey in Jersey. Government of Jersey (gov.je). Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- "Education (Provided Schools) (Jersey) Regulations 2005". Jersey Legal Information Board. 5 May 2006. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ""Major" changes planned to Jersey school funding". bailiwickexpress.com. Bailiwick Express. 4 June 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Victoria College - HMC". hmc.org.uk. The Headmasters' & Headmistresses' Conference (HMC). Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Top 40 least expensive HMC day fees". privateschoolfees.co.uk. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- La Chronique de Jersey, 25 May 1850

- La Chronique de Jersey, 29 September 1852

- La Chronique de Jersey, 2 October 1852

- Kelleher, John D. (1991). The rural community in nineteenth century Jersey (Thesis). S.l.: typescript.

- "Victoria College, Jersey - The Great War Book of Remembrance" (PDF). greatwarci.net/. The Channel Islands and the Great War. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Rowley, J.S. "Victoria College School: A Short History 1929-1956". members.societe-jersiaise.org. Société Jersiaise. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Lowe, Roy (16 May 2012). Education and the Second World War: Studies in Schooling and Social Change. Routledge. p. 193. ISBN 9781136590153. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Lowe, Roy (16 May 2012). Education and the Second World War: Studies in Schooling and Social Change. Routledge. p. 200. ISBN 9781136590153. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Lowe, Roy (16 May 2012). Education and the Second World War: Studies in Schooling and Social Change. Routledge. p. 203. ISBN 9781136590153. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Balleine's History of Jersey, Marguerite Syvret and Joan Stevens (1998) ISBN 1-86077-065-7

- "Postage stamps". Jersey Weekly Post. 1 September 1977.

- Gammell, Caroline (26 February 2008). "Jersey care home 'had shackles and trapdoor'". telegraph.co.uk. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Brown, David (12 January 2016). "Jersey child abuse was covered up, says former police chief". thetimes.co.uk. The Times. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Dykes v. Attorney General". Jersey Legal Information Board. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- Archived 11 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Ahmed, Maria (27 February 2008). "Jersey: child abuse allegations multiply – 2/27/2008". Community Care. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- "Police in cover-up bid over abuse claims against teacher". jerseyeveningpost.com. Jersey Evening Post. 20 October 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Victoria College, Jersey, 1852–1972, Cottrill, D.J., Phillimore & Co Ltd, ISBN 0850332850

- Crossley, Patrick (30 November 2019). "Victoria College - Curriculum review" (PDF). victoriacollege.je. Victoria College. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Victoria College - Uniform and Appearance" (PDF). victoriacollege.je. Victoria College. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "Victoria College Board of Governors - Annual Report 2018 to 2019" (PDF). victoriacollege.je. Victoria College. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Welcome to Victoria College Secondary School". victoriacollege.je. Victoria College. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Mott, Judy, ed. (2013). Independent Schools Yearbook 2012-2013. A&C Black. ISBN 9781408181188.

- Parker 2011, p. 97

- Collenette, Vernon (July 1953). Elizabeth College, Guernsey vs Victoria College, Jersey. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- Parker 2011, p. 88

- "Langford sports centre". gov.je. States of Jersey. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Ansted, David Thomas; Latham, Robert Gordon (1862). The Channel Islands. W.H. Allen. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- Editorial Team, Société Jersiaise, (Autumn 2006), Société Jersiaise Newsletter, vol.45, page 7, (Société Jersiaise: Jersey)

- "Victoria College, Jersey: Bruce House Webpage". Take2theweb.com. 19 December 1914. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- "Victoria College, Jersey: Diarmid House Webpage". Take2theweb.com. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- "Victoria College, Jersey: Sartorius House Webpage". Take2theweb.com. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- "Hatfield College History". Dur.ac.uk. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- "Headmasters at Victoria College". members.societe-jersiaise.org. Société Jersiaise. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "The Shirburnian" (PDF). oldshirburnian.org.uk. The Old Shirburnian Society. July 1944. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "Head retires after a decade at Victoria". jerseyeveningpost.com. Jersey Evening Post. 30 July 2010. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

Bibliography

- Buildings in the Town and Parish of Saint Helier, CEB Brett, 1977

- Victoria College, Jersey, 1852–1972, Cottrill, D.J., Phillimore & Co Ltd, ISBN 0850332850

- The Devenport Years 1967–1991, Stephen Lucas, 2002, ASIN: B0019ZPUKU

- Parker, Bruce (1 December 2011). A History of Elizabeth College, Guernsey. Third Millenium Publishing. ISBN 978-1-906507-503.