Vasojevići

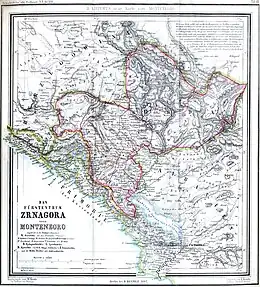

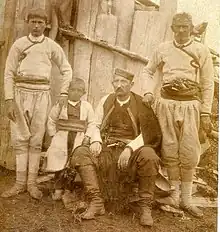

The Vasojevići (Cyrillic: Васојевићи, pronounced [ʋâso̞je̞ʋit͡ɕi]) is a historical highland tribe (pleme) and region of Montenegro, in the area of the Brda. It is the largest of the historical tribes, occupying the area between Lijeva Rijeka in the South up to Bihor under Bijelo Polje in the North, Mateševo in the West to Plav in the East. Likely of Albanian origin, most of the tribe's history prior to the 16th century has naturally been passed on through oral history.

| Part of a series on |

| Tribes of Montenegro |

|---|

|

Although the unofficial center is Andrijevica in north-eastern Montenegro, the tribe stems from Lijeva Rijeka in central Montenegro. The tribe was formed by various tribes that were united under the rule of the central Vasojević tribe. These tribes later migrated to the Komovi mountains and the area of Lim. The emigration continued into what is today Serbia and other parts of Montenegro.

Though sense of tribal affiliation diminished in recent years, is not a thing of a past. Tribal association and organizations still exist (e.g. Udruženje Vasojevića "Vaso"). It could be clearly seen during the 2006 Montenegrin independence referendum with the Vasojevići united opposition.

Geography

The Vasojevići are located in the area between Lijeva Rijeka in the south up to Bihor near Bijelo Polje in the north, Mateševo in the west to Plav in the east. To the south, the Vasojevići border the neighbouring Kuči and Bratonožići tribes. To the east is the border with Albania, while the northeastern boundary has often changed in the past and gradually the Vasojevići expanded in that direction. Lijeva Rijeka is hilly terrain with forests, interspersed with streams and straits, and the same is true of all Upper Vasojevići. However, in Lower Vasojevići, there are more plains around the rivers, so the mountainous terrain is more gentle.

In modern Montenegro, the area of Vasojevići falls into the following municipalities: Berane, Podgorica, Kolašin, Plav and Bijelo Polje (around 15% of Montenegro).[1] One of the highest mountains of Montenegro, Kom Vasojevićki (2,461 m (8,074 ft)), is named after the tribe, and the whole area that the latter inhabits is frequently called “Vasojevići”.[2][3]

Origins

| Part of a series on |

| Albanian tribes |

|---|

|

Likely of Albanian origin, the Vasojevići (Albanian: Vasaj, also Vasoviqi[4] or Vasojeviqi[5]) underwent a process of gradual cultural integration into the neighboring Slavic population.[6][4][7][8][9][10][11][12]

Vasojevići is not a tribe (pleme) with a common patrilineal ancestor, but was formed under the rule of a central tribe that extended its name to many other brotherhoods as it expanded in new territory.[13]

History

Early history

The Vasojevići are first mentioned in a Ragusan Senate report filed by Ragusan merchants and dating to October 29, 1444. At that time, they were not described as a tribe but as a people, as they had not fully formed yet but were still a clan organized as a katun typically used by Vlach and Albanian pastoral communities.[14] The report speaks of the Vasojevići (and of their leader Vaso[15]) as when, together with the Bjelopavlići and the Piperi, they attacked Ragusan merchants and did some material damage to them near the village of Rječica (now Lijeva Rijeka).[16] The Vasojevići are not mentioned in the Vranjina treaty of 1455, which may be explained by the fact that at that time they were apparently a small community in the territory of Piperi, which in the second half of the 15th century encompassed present-day Bratonožići and Lijeva Rijeka.[17] The Vasojevići are mentioned in the 1485 Ottoman defter of Shkodër, where the village of Rječica was known by the alternative name of Vasojević.[18] According to this defter, the Vasojevići and Bratonožići were not yet established tribes[19] and the formation of the Vasojevići as a tribe was a long process that most likely lasted until the end of the 16th century, when they separated from the nahiyah of Piperi as a separate and fully formed tribal unit.[20]

17th century

In 1613, the Ottomans launched a campaign against the rebel tribes of Montenegro. In response, Vasojevići along with the tribes of Kuči, Bjelopavlići, Piperi, Kastrati, Kelmendi, Shkreli and Hoti formed a political and military union known as “The Union of the Mountains” or “The Albanian Mountains”. In their shared assemblies, the leaders swore an oath of besa to resist with all their might any upcoming Ottoman expeditions, thereby protecting their self-government and disallowing the establishment of the authority of the Ottoman Spahis in the northern highlands. Their uprising had a liberating character, with the aim of getting rid of the Ottomans from their territories.[21][22] Mariano Bolizza recorded in 1614 that Vasojevići had a total of 90 houses, of the Serbian Orthodox faith. It was commanded by Nicolla Hotaseu (Nikolla Hotasev) and Lale Boiof (Lale Bojov) and could field up to 280 soldiers.[23]

In 1658, the seven tribes of Kuči, Vasojevići, Bratonožići, Piperi, Kelmendi, Hoti and Gruda allied themselves with the Republic of Venice, establishing the so-called “Seven-fold banner” or “alaj-barjak”, against the Ottomans.[24] In 1689, an uprising broke out in Piperi, Rovca, Bjelopavlići, Bratonožići, Kuči and Vasojevići, while at the same time an uprising broke out in Prizren, Peja, Pristina and Skopje, and then in Kratovo and Kriva Palanka in October (Karposh's Rebellion).[25]

18th and 19th century

During the Austro-Turkish War, which began in 1737, the Serbian patriarch Arsenije IV Jovanović Šakabenta organized an uprising and the Orthodox population of Serbia and the Brda revolted. Alongside the patriarch, chiefs of the Vasojevići and other Brda tribes joined the Austrian forces in Serbia and helped them take Niš and Novi Pazar, in July 1737.[26] Led by the Serbian patriarch and the voivode Radonja Petrović of the Kuči tribe, another 3,000 highlanders arrived in a deserted Novi Pazar, a day after the Austrian forces had withdrawn. On their way home, some of the Vasojevići and Kuči highlanders looted and burned Bihor.[27][28][29] The Ottoman reprisals against the insurgents began in October 1737 and had terrible consequences for the people living in the valleys of the Ibar, West Morava, Lim and Tara rivers. The Ottoman army of Hodaverdi Pasha Mahmudbegović burned and destroyed every village in its path, which caused the migration of thousands of Serbs and also Catholic Albanians.[28] By the end of 1737, the Ottoman army had ravaged the entire Vasojevići region, burning and destroying almost every village from Bijelo Polje to the Komovi Mountains.[30][31] Most of the churches and monasteries were also burnt and destroyed, such as the monasteries of Đurđevi Stupovi and Šudikovo in 1738, the latter never being rebuilt. The defeat of Austria against the Ottomans led to a massive migration of the population of the Upper Lim valley, which became depopulated while part of its inhabitants was enslaved or even exiled to Metohija in 1739.[27][30]

The Upper Vasojevići region was de facto incorporated into the Principality of Montenegro in 1858, after the Battle of Grahovac,[32] and confirmed 20 years later by the Treaty of Berlin, while the Lower Vasojevići area remained under Ottoman rule.[33]

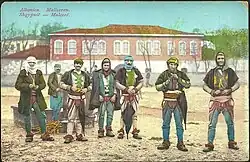

In 1860, the Montenegrin government, as part of an assimilation campaign, issued an order that certain embroideries and ornaments were to be removed from various parts of the Vasojevići women's costume, such as the džupeleta, jackets or aprons, and that traditional Montenegrin costumes were to be worn instead. Later on officials were sent to Vasojevići to enforce the ruling. Despite, the women of the Vasojevići tribe would retain their traditional folk costume until the beginning of 20th century.[34]

20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century, while still under Ottoman rule, the Lower Vasojevići had become radicalized and were quick to stir up trouble. In a region on the border between Montenegro and the Ottoman Empire, this was a challenge for both states.[35] In 1911, an Ottoman offer to bring the Lower Vasojevići back under the authority of the Porte was not successful.[35] Failing to pacify the tribesmen, the Ottoman authority decided to recruit and send them away from their homeland. This had the unexpected result that the Lower Vasojevići revolted in the summer of 1912, with the support of the Montenegrins.[36] With the help of paramilitaries from Rugova, Plav, Gusinje and other neighboring areas, the Ottoman regular army was able to suppress the revolt and devastated the Lower Vasojevići villages and crops, while the monastery of Đurđevi stupovi was looted and burned.[37]

During World War I, the Kingdom of Montenegro was occupied by the Austro-Hungarian army from January 1916 until the end of the war. A prominent member of the Vasojevići, the Brigadier-General Radomir Vešović was given the task of disbanding the Montenegrin army and negotiating terms with the occupying forces. Having failed to do so, the general killed the man sent by the Austrians to arrest him. This act of defiance triggered a resistance movement in Montenegro, especially among Vešović's Vasojevići kinsmen, followed by a harsh campaign of reprisals by the Austrians.[38]

Following the end of the war, a Great National Assembly was held in Podgorica, on 19 November 1918, to decide the future status of Montenegro. The election resulted in a victory for the Whites (Serbian: bjelaši), who supported unilateral unification with Serbia, while those who saw it as an annexation of Montenegro by Serbia were called the Greens (Serbian: zelenaši). Together with the Bjelopavlići, the Drobnjaci, part of the Nikšići and the Grahovljani, the Vasojevići were among the tribes that supported the Whites and, after their victory, celebrated an effective pan-Serbianism.[39]

World War II

During the Second World War, the Vasojevići were divided between the two armies of Serb Chetniks (royalists) and Yugoslav Partisans (communists) that were fighting each other[40] (vojvoda Pavle Đurišić formed the most successful Chetnik units out of mainly Vasojevići). As a result, the conflict spread within the tribal structures.[40] The partisans formed a distinct Vasojević battalion. In battles, against Chetniks and the Fascist Italian army, it routed 200 Chetniks and 160 Italian soldiers in defense of the position of Pešića Lake during the advance of the Chetniks from Kolašin.[41]

Breakup of Yugoslavia

As with other Montenegrin tribes, and although the sense of tribal belonging did not entirely cease, the Vasojevići as a tribe ceased to exist at the time of Communist Yugoslavia. However, the collapse of the Yugoslav state favored the resurrection of the northern Montenegrin tribes, traditionally closer to Belgrade.[42] Tribal meetings were arranged in these historical tribal areas under the influence of Momir Bulatović's Socialist People's Party and the Serbian Orthodox Church, with the aim of countering the separatist authorities in Montenegro.[42] Historically having close ties to Serbia, the Vasojevići were among the strongest supporters of Bulatović, who could count on the majority of the population of Andrijevica and Berane, the main towns in the Vasojevići region.[43] On 12 July 1994, at a traditional St. Peter's Day gathering, prominent members of the tribe decided that their region would join Serbia if Montenegro was to secede from the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.[44]

21st century

In May 2006, Montenegro gained independence after a referendum on the future of the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro. However, 72% of voters in Andrijevica municipality, the unofficial centre of the Vasojevići region, voted against Montenegrin independence. It was the second highest result against breaking the state union with Serbia (after Pluzine municipality).[45]

The People's Assembly of Vasojevići stated many times that, apart from being Montenegrin, all Vasojevići are Serb[46][47] and, thus, strongly oppose and have always opposed Montenegrin secession from Yugoslavia.[48][49] The Montenegrin census of 2003 revealed that 89,81% of the Vasojevići declared themselves as Serb while 9,43% declared themselves as Montenegrin. In the 2011 census, in most settlements linked to the Vasojevići the majority identified themselves as Serbs. In Andrijevica about 2/3 identified as Serbs and 1/3 as Montenegrins.[50]

2010s

During the War in Ukraine, some locals of villages of Andrijevica, part of the Vasojevići tribe, decided to sell and give up land for free to Russia, stating that "we are brothers".[51]

Anthropology

Culture

It is a tradition of all brotherhoods to show respect to ancestors by knowing precisely genealogy and the history of the tribe and a family. This also allows members of the clan to be unite, to act together and always to recognise kin.[52] In terms of traditional customs, up to the end of the 19th century traces of a variant of the northern Albanian kanuns remained in use in Vasojevići.[53] Two story houses were known as Kula[54]

The traditional clothing of the Vasojevići resembles that of other tribes of the Albanian-Montenegrin borderland. In particular, the woman's garment, a woolen bell-shaped skirt called oblaja or džupeleta (the latter came through Turkish from the Arabic jubba[55]), is similar to the xhubleta worn by Albanian women from neighbouring Malisor tribes.[56][57][58]

Srbljaci and Ašani

From their first mentions in the mid-15th century until the end of the 17th century, the Vasojevići remained in their Brda cradle, the centre of which was Lijeva Rijeka. At that time, the neighbouring upper Lim valley was inhabited by Serbs, with whom the Vasojevići were in regular contact and whom they called Srbljaci (sing. Srbljak).[59] However, these original Srbljaci emigrated en masse after 1651 and were slowly replaced by various brotherhoods and families from Montenegro and the Brda.[60] The Vasojevići themselves gradually expanded into the upper Lim valley in the 18th century and began to call all the other brotherhoods and families they encountered Srbljaci, whether they were recent newcomers from other Brda or Montenegrin tribes, or remaining descendants of the original Srbljaci.[61]

At the same time a similar term emerged, Ašani (sing. Ašanin), which the Vasojevići used to refer to people living in Has, the name then given to the region around Berane.[62] The name Has was then used by the Ottomans to designate an administrative unit of which Berane was the center, and its inhabitants were called the Ašani not only by the Vasojevići, but by the mountain tribes in general. And since Berane was at that time inhabited only by Srbljaci, the name Ašanin acquired the same meaning as Srbljak in the region.[63]

Therefore, while Srbljaci originally had a broader meaning than Ašani, the two terms gradually became synonymous with each other. Thus, since the 19th century, both terms have been used to refer to people of another origin living in the Vasojevići region.[2][3][52]

Folk traditions

The Vasojevići are considered to be one family or clan, descended from a single male ancestor called Vasoje. There are various folk tales about this ancestor, and the aforementioned Vasoje stands out among them, as does Vaso, who is said to be his descendant, although these two names are often mixed up in different legends.[64] This eponymous ancestor is said to have settled in Lijeva Rijeka at a time when the area was desolate, where he would have built a house on the right bank of the Nožica stream.[20] Among the legends about the origins of the tribe, one considers that Vasoje was the grandson of Vukan Nemanjić and that Vaso was himself the great grandson of Vasoje.[65] According to a folk myth, the three Vasojevići brotherhoods are descended from Raje, Novak and Mioman, the three sons of Vaso.[66]

Vaso's descendants gradually expanded to the north-east and inhabited the region by the river Lim, called Polimlje – the area around the Komovi mountains, Andrijevica and Berane.[67][3][52] Thus, they formed the largest tribe (pleme) of all seven highland tribes of Montenegro (i.e. Vasojevići, Moračani, Rovčani, Bratonožići, Kuči, Piperi and Bjelopavlići). Part of the tribe that stayed free from the Turkish rule lives in the area of Lijeva Rijeka and Andrijevica (Upper Nahija) – they are all called Upper Vasojevići. Lower Vasojevici (or Lower Nahija) inhabited the area of Berane. Most of the Lower Vasojevići were within the Turkish reign until Balkan Wars in the 20th century.[3]

Johann Georg von Hahn recorded one of the first oral traditions about Vasojevići from a Catholic priest named Gabriel in Shkodër in 1850. According to it the first direct male ancestor of the Vasojevići was Vas Keqi, son of a Keq a Catholic Albanian who fleeing from Ottoman conquest settled in a Slavic-speaking area that would become the historical Piperi region. His sons, the brothers Lazër Keqi (ancestor of Hoti), Ban Keqi (ancestor of Triepshi), Kaster Keqi (ancestor of Krasniqi) and Merkota Keqi (ancestor of Mrkojevići) had to abandon the village after committing murder against the locals, but Keq and his younger son Piper Keqi remained there and Piper Keqi became the direct ancestor of the Piperi tribe.[68][69][70]

In the 18th century, the folklore of the tribe was influenced by the Orthodox millenarianism that had developed during the mid Ottoman era. According to one such folk legend, an elder of the Vasojevići, Stanj, foretold Greek priests the advent of a Serbian messiah, a dark man (crni čovjek) who would liberate the Serbs from the Turks. These myths as part of the official Serbian Orthodox doctrine provided both a de facto recognition of Ottoman rule and the denial of its legitimacy.[71]

Ethnographic accounts

According to a memorandum created by the Austro-Hungarian consul F.Lippich, which studied the demographic structure of the area, the Vasojevići are considered the northern linguistic border of Albanian and constitute a case of slavicised Albanians.[72][73]

Marie Amelie von Godin in her travels still reported traces of bilingualism in the area of Vasojevici. According to her reports, although Albanian was no longer spoken in the area, some laments and oaths were still being sung and recited in Albanian.[74]

Brotherhoods

The people of Vasojevići consider themselves as the descendants of three Vaso sons: Rajo, Novak and Mioman. Hence the three great clans (Serbian: bratstva) of the tribe:[75][76]

- Rajevići

- Novakovići

- Miomanovići

In his book Pleme Vasojevići, published in 1935, the historian Radoslav Vešović, who was a member of the tribe, describes the structure of the Vasojevići.[77] The list of families was exhaustive at the time of writing, but new families may have developed since then. It happens that with a very distant genealogy, slight variations of names, chronology and relationships exist simultaneously, but there is no doubt among the Vasojevići members as to which family belongs to which brotherhood, branch and sub-branch.[78] In fact, no Vasojevići family has ever questioned the structure described below.[79][78]

|

Rajevići is the biggest branch. It is in turn divided into three branches Families that descend from Lopaćani are:

Families that are descendants of Dabetići are:

Families of Kovačevići branch are:

|

Novakovići is the second biggest branch. All the families of Novakovići brotherhood are as follows:

|

Miomanovići is the smallest brotherhood of the Vasojevići. The families are:

|

Notable people

By the beginning of World War II, there were around 3,600 Vasojevići “houses” in Polimlje and Lijeva Rijeka.[80] Many famous Serbs, Montenegrins, or people of Serbian or Montenegrin descent, are Vasojevići by origin, e.g.:

- Karađorđe Petrović, Serbian revolutionary, leader of the Serbian Revolution and first Grand Vožd of Serbia[81]

- Slobodan Milošević - former President of Serbia and of Yugoslavia.[82]

- Radomir Vešović - War Minister of the Kingdom of Montenegro, General of Division in III Army of Kingdom of SHS.[83]

- Gavro Vuković - a jurist, senator of the Principality of Montenegro, a military commander, Yugoslav politician and writer.[84]

- Avram Cemović, military officer who commanded Montenegrin units that captured Berane from Ottomans [85]

- Momčilo Cemović - Presidents of the Executive Council of the Socialist Republic of Montenegro (Prime Minister) from 1978 till 1982. Finance Minister of Yugoslavia from 1974 to 1978.[86]

- Milla Jovovich - American actress, model, and musician [87]

- Petar Bojović - one of four famous Serbian vojvode (field-marshal) in Balkan Wars and World War I.[88]

- Đorđije Lašić, Montenegrin Serb military officer of the Royal Yugoslav Army.

- Dragan Nikolić - one of the most recognizable actors in Serbian cinema.[89]

- Puniša Račić - Serbian and Yugoslav Radical politician who, in 1928, assassinated Croatian politician Stjepan Radić.[90]

- Svetozar Marković - an influential Serbian political activist of the 19th century.[91]

- Mihailo Lalić - a famous novelist of Serbian and Montenegrin literature. He is considered by some to be among the greatest Montenegrin authors.[91]

- Radovan Zogović - one of the greatest Montenegrin poets of the 20th century.[91]

- Jelena Janković - a Serbian professional female tennis player - formerly nr 1 ranked player in a WTA list.[91]

- Milutin Šoškić - a legendary Serbian goalkeeper who played for SFR Yugoslavia.[91]

- Borislav Milošević - Serbian diplomat [82]

- Sofija Milošević - Serbian fashion model

- Žarko Obradović - Serbian politician and a former Minister of Education in the Government of Serbia.

- Slavica Đukić Dejanović - Serbian politician, former Minister of Health and former President of the National Assembly of Serbia

- Ljubiša Jokić - former general in the Military of Serbia and Montenegro

- Divna Veković - first female medical doctor in Montenegro.

- Vjera Mujović -an actress and writer of novels

- Lidija Vukićević - Serbian actress and politician

- Slavko Labović - Serbian-Danish actor

- Milija and Pavle Bakić, co-founders of Galatasaray football club

- Dragan Labović - Serbian basketball player

- Budislav Šoškić - Montenegrin communist and President of the People's Assembly of Socialist Republic of Montenegro

- Dejan Šoškić - Serbian economist, former Governor of the National Bank of Serbia

- Milić Vukašinović - drummer, rock singer and guitarist, most notable for his stint with Bijelo dugme.

- Bora Đorđević, famous Serbian musician and singer

- Željko Joksimović, famous Serbian musician and singer

- Boban Rajović, famous Montenegrin folk singer

- Blažo Rajović, Montenegrin footballer

- Mileta Rajović, Danish footballer of Serb Montenegrin origin.

- Goran Vukošić, popular Montenegrin folk singer.

- Marko Vešović, Montenegrin footballer.

- Siniša Dobrašinović, Montenegrin-born Cypriot football player

- Žarko Zečević, former Serbian basketball player, former football administrator and businessman

- Vladimir Dašić, Montenegrin basketball player

- Bojan Bakić, Montenegrin basketball player

- Boris Bakić, Montenegrin basketball player

- Ivan Djurkovic, Montenegrin handball player

- Sonja Barjaktarović, Montenegrin handball player

- Tanja Bakić. Montenegrin poet, essay and non-fiction writer

- Vasilije Tomović, Montenegrin chess master

- Mitar Milošević famous writer

- Đorđije Pajković -Montenegrin Yugoslav politician, Presidents of the Executive Council of the Socialist Republic of Montenegro (Prime Minister) from 1962-1963

- Čedo Vuković - Montenegrin writer

- Stefan Babović - Serbian football player currently playing for FK Partizan and the Serbia national football team.

- Branislav Šoškić - Montenegrin economist and politician, President of the Socialist Republic of Montenegro's Presidency in 1985-1986

- Stevo Vasojević* - legendary ancestor of the Vasojevići tribe and character in the Kosovo Cycle

- Hadži-Prodan Gligorijević - Serbian voivode in the First Serbian Uprising[92]

References

- "Pribijanje uz rođake". Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2009-02-19.

- Vešović 1935.

- Cemović 1993.

- Elsie, Robert (2015). The Tribes of Albania: History, Society and Culture. London: I.B. Tauris. p. 3. ISBN 978-1784534011.

The now Slavic-speaking Kuçi [Kuči] tribe of Montenegro, for instance, was originally Albanian-speaking. The same may be true, at least in part, of the Montenegrin Vasoviqi [Vasojevići] and Palabardhi [Bjelopavlići] tribes. On the other hand, many of the Albanian tribes took their origins from the north, i.e. from Montenegro and even from Herzegovina, and were no doubt originally Slavic-speaking.

- Duicu, Ioana (2015). "Metal Adornments Of/With Balkan Influences, Components Of Women's Folk Costumes In Oltenia And Banat" (PDF). Cogito. “Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University: 126. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-11-11. Retrieved 2022-06-21.

- Gjergji, Andromaqi (2004). Albanian Costumes Through the Centuries: Origin, Types, Evolution. Tirana: Academy of Sciences of Albania, Institute of Folc Culture. p. 118. ISBN 9789994361441. Archived from the original on 2023-03-12. Retrieved 2021-05-17.

This also explains the severity of the measures with which the official circles of Cetinje tried to eliminate the folk costume of several Albanian clans in Montenegro, as one of the means for their denationalisation. Thus, in 1860, the government in Cetinje first issued the order that ornaments and embroideries must be removed from different parts of the costume of the women of the Vasaj tribe (Vasojevic) such as on the xhubleta, aprons, jackets etc. and Montenegrin garments worn instead; then the governor sent men to the Vasaj who "took the multicolour coats from the women's clothes chests so the people would wear the Montenegrin costume. He did the same thing in the neighbouring zones of the Moraça, Ravcaj, Bratonozhiq and other, because there too, a similar women's costume was worn" (121, p.823). Despite the drastic measure, the women of the Vasaj clan retained their folk costume until the beginning of XX century.

- Arifi, Arben; Tetaj, Luan (2020). "The Monastery of Deçan and the Attempts to Appropriate It". Journal of International Cooperation and Development. Richtmann Publishing: 67. Archived from the original on 2021-12-28. Retrieved 2022-02-02.

In Montenegro, Albanian tribes such as Kuçi, Bjellopavliq (Palabardhët), Piprraj, Vasoviq, and others were among the assimilated ones

- Miranda, Vickers (1998). Between Serb and Albanian: A History of Kosovo. Hurst & Company. p. 8.

In Kosovo, especially in its eastern part, most Albanians were gradually assimilated into the Eastern Orthodox faith by numerous methods, including the baptism of infants with Serbian names and the conducting of all religious ceremonies such as marriages in the Serbian language. In Montenegro entire tribes such as the Kuc, Bjellopavliq, Palabardha, Piprraj and Vasovic were assimilated; those who resisted assimilation retreated into the hills of what is now northern Albania.

- Murati, Qemal (2012). "Sprovë për një fjalor etimologjik onomastik Shqiptar". Studime Albanologjike. ITSH. 6: 19. Archived from the original on 2022-05-22. Retrieved 2022-06-21.

Procesi i kalimit të elementit shqiptar në atë serb me rrugë të ndryshme asimilimi ka ndodhur te shumë fise të Malit të Zi, në Kuç etj., si p.sh. te Piperët, te Vasojeviçët etj.

- Rudolf, Vogel (1964). Südosteuropa-Schriften - Volume 6. p. 176.

Auch die montenegrinischen Stämme der Piperi und Vasojevići sind ihrer Herkunft nach stark albanisch fundiert

- Zojsi, Rrok (1977). Buda, Aleks (ed.). "Survivances de l'ordre du fis dans quelques micro-régions de l'Albanie". La Conférence nationale des études ethnographiques (28-30 juin 1976): 196–197.

Pourtant, quelques groupes d'un fis, éloignés excessivement de leur base, entrèrent en rapports socio-économiques avec d'autres fis du nouvel emplacement et tombèrent sous leur influence, comme p. ex., des différents frères du fis de Keç Panta, le Hot et le Triesh restèrent albanais, cependant que les Vasojeviq et le Pipër se slavisèrent. Quoique ayant perdu la base économique commune et les traditions culturelles communes, ils n'en conservèrent pas moins l'idée d'une origine commune.

- Ulqini, Kahreman (1983). "Tradition and history about the Albanian origin of some Montenegrin tribes". Kultura Popullore. 03 (1al): 121–128. Archived from the original on 2022-07-09. Retrieved 2022-08-01.

- Vucinich, Wayne S. (1975). A study in social survival: the katun in Bileća Rudine. University of Denver. p. 30. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- Gorunović 2017, pp. 1211–1212.

- M. Vukić, Svetozar (1969). Vasojevići u ime države Crne Gore 1861: Imena učesnika u pohodu (in Serbian). Prijepolje: Izdanje pisca. p. 7.

Prema podatku Konstantina Jirečeka, koji se čuva u dubrovačkom arhivu Vasojevići se prvi put pominju 1444. godine pod nazivom apudmedomum od Rikavac. Pominju se zajedno Bjelopavlići, Piperi i et vasojevički Vaso, kao napadači na dubrovačke trgovce.

- Dašić 2011, pp. 10, 144.

- Dašić 2011, p. 146.

- Pulaha, Selami (1974). Defter i Sanxhakut të Shkodrës 1485. Academy of Sciences of Albania. pp. 371, 424–425. Archived from the original on 2020-08-09. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

- Vlado Strugar (1987). Prošlost Crne Gore kao predmet naučnog istraživanja i obrade. Crnogorska akademija nauka i umjetnosti. p. 135. ISBN 9788672150018.

- Gorunović 2017, p. 1212.

- Kola, Azeta (2017). "From Serenissima's Centralization to the Selfregulating Kanun: The Strengthening of Blood Ties and the Risie of Great Tribes in Northern Albania From 15th to 17th Century". Acta Histriae: 369.

- Mala, Muhamet (2017). "The Balkans in the anti-Ottoman projects of the European Powers during the 17th Century". Studime Historike (1–02): 276. Archived from the original on 2021-05-16. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

- Bolizza, Mariano. "Report and Description of the Sanjak of Shkodra". Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- Mitološki zbornik. Centar za mitološki studije Srbije. 2004. pp. 24, 41–45.

- Belgrade (Serbia). Vojni muzej Jugoslovenske narodne armije (1968). Fourteen centuries of struggle for freedom. The Military Museum. p. xxviii. Archived from the original on 2023-03-12. Retrieved 2016-10-13.

- Šćekić, Leković & Premović 2015, p. 86.

- Barjaktarović 1973, p. 178.

- Dašić 2011, p. 269.

- Šćekić, Leković & Premović 2015, p. 87.

- Dašić 2011, p. 271.

- Šćekić, Leković & Premović 2015, p. 89.

- Morrison 2009, p. 21.

- Miladinović 2021, p. 134.

- Gjergji, Andromaqi (2004). Albanian Costumes Through the Centuries: Origin, Types, Evolution. Tirana: Academy of Sciences of Albania, Institute of Folc Culture. p. 118. ISBN 9789994361441.

This also explains the severity of the measures with which the official circles of Cetinje tried to eliminate the folk costume of several Albanian clans in Montenegro, as one of the means for their denationalisation. Thus, in 1860, the government in Cetinje first issued the order that ornaments and embroideries must be removed from different parts of the costume of the women of the Vasaj tribe (Vasojevic) such as on the xhubleta, aprons, jackets etc. and Montenegrin garments worn instead; then the governor sent men to the Vasaj who "took the multicolour coats from the women's clothes chests so the people would wear the Montenegrin costume. He did the same thing in the neighbouring zones of the Moraça, Ravcaj, Bratonozhiq and other, because there too, a similar women's costume was worn" (121, p.823). Despite the drastic measure, the women of the Vasaj clan retained their folk costume until the beginning of XX century.

- Miladinović 2021, p. 219.

- Miladinović 2021, p. 224.

- Miladinović 2021, p. 224-225.

- Roberts 2007, p. 318.

- Banac 1988, p. 285.

- Djilas, Milovan (1977). Wartime. ISBN 9780151946099. Archived from the original on 2022-05-05. Retrieved 2016-10-13.

- Dedijer, Vladimir (1990). The War Diaries of Vladimir Dedijer. University of Michigan. p. 125. ISBN 0472101102. Archived from the original on 2022-04-28. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- Morrison 2009, p. 175.

- Morrison 2009, p. 159.

- Pavlović 2003, p. 101.

- "OSCE Referendum o drzavnom statusu" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- Jelić, Ilija (1929). Vasojevićki Zakon od Dvanaest Točaka [Vasojevići's Law in Twelve Points] (in Serbian). Belgrade: Srpska Kraljevska Akademija.

- Milija Komatina, Crna Gora I Srpsko Pitanje: Prilog Izucavanju Integrativnih i Dezintegrativnih Tokova (Montenegro and the Serbian Question: A Contribution to the Study of Integrative and Disintegrative Currents) (Belgrade: Inter Ju Press, 1966), page 171

- "Udruzenie Vasojevicia Vaso". Archived from the original on 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2009-02-19.

- "Vasojevici za Srpstvo i Jugoslaviju". Archived from the original on 2011-06-16. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- "2011 census - Montenegro". Monstat. Archived from the original on 2020-06-05. Retrieved 2021-12-28.

- "Васојевићи нуде земљу Путину". Archived from the original on 2014-12-13. Retrieved 2014-12-13.

- Dragović 1997.

- Martucci, Donato (2021). "Il mio destino balcanico" L'illirismo di Antonio Baldacci tra viaggi di esplorazione e senilità. University of Salento: Palaver. p. 317. Archived from the original on 2021-05-17. Retrieved 2021-05-17.

Nella tornata del 12 aprile 1940 al Convegno di Tirana degli Studi Albanesi, discutendosi dell'importanza del Kanun per il folklore io feci osservare che esso vigeva nel 1890 e 1891 (quando esplorai per la prima volta il Montenegro) ancora come fondamento giuridico consuetudinario nelle tribù montenegrine dei Kuči, dei Vasojevići e dei Piperi (che fino al Trattato di Berlino non facevano parte del Principato del Montenegro e continuavano ad essere considerate nel dominio ottomano): fu in quella tornata che proposi diestendere le ricerche sul Kanun nelle regioni suddette per raccogliervi le ultime vestigia colà resistenti di esso.

- Krasniqi, Mark (1982). "Gjurmë e gjurmime". Studime Etnografike: 342. Archived from the original on 2023-03-12. Retrieved 2021-05-17.

- Menković 2007, p. 176.

- Maretić, Tomislav (1962). Zbornik za narodni život i običaje južnih Slavena. Jugoslavenska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti.

- Gjergji, Andromaqi (2004). Albanian Costumes Through the Centuries Origin, Types, Evolution. Indiana University: Acad. of Sciences of Albania, Inst. of Folc Culture. p. 185. ISBN 9789994361441. Archived from the original on 2023-03-12. Retrieved 2023-02-03.

- Menković 2007, pp. 174–175.

- Lutovac 1935, p. 109.

- Lutovac 1935, p. 108.

- Lutovac 1935, pp. 108–109.

- Lutovac 1935, p. 110.

- Lutovac 1935, p. 111.

- Vešović 1935, p. 82.

- Gorunović 2017, p. 1213.

- Dragović 1997, p. 6.

- Vešović 1935, p. 104.

- von Hahn, Johan Georg; Elsie, Robert (2015). The Discovery of Albania: Travel Writing and Anthropology in the Nineteenth Century. I. B. Tauris. pp. 125–35. ISBN 978-1784532925. Archived from the original on 2023-03-12. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

- Drançolli, Jahja (2017). "ŠUFFLAY - NJERI NDËR ALBANOLOGËT MË TË SHQUAR TË BOTËS". Studime Albanologjike. ITSH: 47.

- Ulqini, Kahreman (1983). "Tradition and history about the Albanian origin of some Montenegrin tribes". Kultura Popullore. 03 (1al): 121–128. Archived from the original on 2022-07-09. Retrieved 2022-08-01.

- Roudometof, Victor (1998). "From Rum Millet to Greek Nation: Enlightenment, Secularization, and National Identity in Ottoman Balkan Society, 1453–1821" (PDF). Journal of Modern Greek Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- Stavro, Skendi (2015). The Albanian National Awakening. Princeton University Press. p. 33.

According to a memorandum sent on 20 June 1877, by the Austria-Hungary's Consul in Skodra F. Lippich to Vienna: The northern linguistic Albanian frontier runs from west to east, starting from the Adriatic coast somewhat below Antivari, above the mountain ridge and the northwestern corner of the Shkodër lake, following the Sem (Zem) upstream above Fundina through Kuči to Vasojević and Kolašin; the latter two districts, although Serbian-speaking in the majority, still seem to be in part of Albanian origin—perhaps the only instance of a slavization of Albanians.

- Verli, Marenglen (2009). "The data of the year 1877 for the main features of Albanians and the demographic structure of some sancaksjournal=Studime Historike". Studime Historike (1–02): 158. Archived from the original on 2021-05-17. Retrieved 2021-06-05.

- Gostentschnigg, Kurt (2017). Wissenschaft im Spannungsfeld von Politik und Militär Die österreichisch-ungarische Albanologie 1867-1918. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. p. 189. ISBN 9783658189112. Archived from the original on 2023-03-12. Retrieved 2021-06-05.

- Vešović 1935, pp. 178–179.

- Dašić 2011, pp. 161–162.

- Vešović 1935, pp. 179–233.

- Dragović 1997, p. 8.

- Vešović 1935, p. 179.

- Vešović 1935, p. 233.

- Banac 1988, p. 45; Roberts 2007, p. 118; Morrison 2009, p. 21.

- "Borislav Milošević laid to rest in Montenegro". B92 News. 1 February 2013. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- Лесковац, Младен; Форишковић, Александар; Попов, Чедомир (2004). Српски биографски речник (in Serbian). Будућност. p. 176. ISBN 9788683651627. Archived from the original on 2023-03-12. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

Потиче из познате официрске породице братства Вешовића. Основну школу

- Dimitrije-Dimo Vujovic, Prilozi izucavanju crnogorskog nacionalnog pitanja /The Research of the Montenegrin Nationality/ (Niksic: Univerzitetska rijec, 1987), p. 172.

- (Guberinić 1996, p. 145):"Бригадир Авро Цемовић (1864-1914) Бригадир Аврам-Авро Цемовић, рођен је на Бучу."

- Momcilo Cemovic, 1993, "Preci i potomci"

- Rakočević, Donko (August 14, 2017). "МИЛА ЈОВОВИЋ: Снимићу филм о Голом отоку!". Sedmica (in Montenegrin). Archived from the original on November 13, 2017. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- "Petar Bojović | Petar Bojović | Biography". Archived from the original on 2021-05-17. Retrieved 2021-05-17.

- "eSpona - Za Dragana Nikolića je Crna Gora bila utočište". espona.me. Archived from the original on 2016-03-27.

- "Novosti". Archived from the original on 2021-05-17. Retrieved 2021-05-17.

- "Najveće pleme u Crnoj Gori koje voli da vlada". Archived from the original on 2021-05-17. Retrieved 2021-05-17.

- Šćekić, Leković & Premović 2015, p. 98.

Bibliography

- Banac, Ivo (1988) [1st pub. 1984]. The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9493-2.

- Barjaktarović, Mirko (1973). "Etnički razvitak Gornjeg Polimlja" [Ethnic development of the upper Lim valley] (PDF). Glasnik Cetinjskog muzeja (in Serbian). VI: 161–198.

- Dašić, Miomir (2011) [1st pub. Narodna knjiga:1986]. Vasojevići: od pomena do 1860 [The Vasojevići: from mentions until 1860] (PDF) (in Serbian). Nikšić: Izdavački centar Matice srpske. ISBN 9789940580049.

- Cemović, Marko P. (1993). Vasojevići: istorijska istraživanja [The Vasojevići: historical research] (in Serbian) (2nd ed.). Belgrade: Izdavački savjet zavičajnog udruženja Vasojevića. ISBN 9788682233022.

- Dragović, Ivan R. (1997). Ko su i od koga su Dragovići i Lekići iz Đulića [Who are and from whom are the Dragovići and Lekići from Đulić?] (in Serbian). Belgrade. ISBN 9788690189717.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gorunović, Gordana (2017). "Mihailo Lalić and Serbian Ethnology: Ethnography and Mimesis of Patriarchal Society in Montenegrin Highlands". Issues in Ethnology and Anthropology. 12 (4): 1203–1232. doi:10.21301/eap.v12i4.10.

- Lalević, Bogdan; Protić, Ivan (1903). Vasojevići u crnogorskoj granici [The Vasojevići in the Montenegrin border] (in Serbian). Belgrade: Srpska Kraljevska Akademija.

- Lutovac, Milisav B. (1935). "Srbljaci u Gornjem Polimlju" [The Srbljaci in the Upper Lim Valley]. Glasnik etnografskoj muzeja u Beogradu (in Serbian). X: 108–115.

- Menković, Mirjana (2007). "Ženska suknja džubleta/džupeleta. Prilog proučavanju odevnih predmeta iz zbirke narodnih nošnji Crne Gore u Etnografskom muzeju u Beogradu" [Women's skirt džubleta/džupeleta. Contribution to studying clothing items contained in the collection of the Montenegrin national costumes of the Museum of Ethnography in Belgrade] (PDF). Glasnik etnografskoj muzeja u Beogradu (in Serbian). 71: 169–190.

- Miladinović, Jovo (27 October 2021). Heroes, Traitors, and Survivors in the Borderlands of Empires. Military Mobilizations and Local Communities in the Sandžak (1900s-1920s) (PhD). Humboldt University of Berlin.

- Morrison, Kenneth (2009). Montenegro: A Modern History. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-4416-2897-8.

- Pavlović, Srđa (2003). "Who are Montenegrins? Statehood, identity, and civic society". In Bieber, Florian (ed.). Montenegro in Transition. Problems of Identity and Statehood. Baden-Baden: Nomos. pp. 83–106. ISBN 9783832900724.

- Roberts, Elizabeth (2007). Realm of the Black Mountain. A History of Montenegro. London: C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-185065-868-9.

- Šćekić, Radenko; Leković, Žarko; Premović, Marijan (2015). "Political Developments and Unrests in Stara Raška (Old Rascia) and Old Herzegovina during Ottoman Rule". Balcanica (XLVI): 79–133. doi:10.2298/BALC1546079S.

- Vešović, Radoslav-Jagoš (1935). Pleme Vasojevići u vezi sa istorijom Crne Gore i plemenskim životom susjednih Brda [The Vasojevići tribe in connection with the history of Montenegro and the tribal life of the neighboring Brda] (in Serbian). Sarajevo: Državna štamparija u Sarajevu.

- Zlatar, Zdenko (2007). The poetics of Slavdom: the mythopoeic foundations of Yugoslavia. Vol. 1. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-8118-0.

External links

- "Васојевички Закон у 12 точака". Пројекат Растко Цетиње. 1929 [1830].

- http://sites.google.com/site/vasojevici