Zafirlukast

Zafirlukast is an orally administered leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA) used for the chronic treatment of asthma. While zafirlukast is generally well tolerated, headache and stomach upset often occur. Some rare side effects can occur, which can be life-threatening, such as liver failure. Churg-Strauss syndrome has been associated with zafirlukast, but the relationship isn't thought to be causative in nature. Overdoses of zafirlukast tend to be self-limiting.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Accolate[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697007 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Unknown |

| Protein binding | >99% (albumin)[1] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP2C9-mediated) |

| Metabolites | hydroxylated metabolites[1] |

| Elimination half-life | 10 hours |

| Excretion | Fecal[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.189.989 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C31H33N3O6S |

| Molar mass | 575.68 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 138 to 140 °C (280 to 284 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Zafirlukast, like other LTRAs, works by inhibiting the immune system. Through its action on inflammatory cells in the lungs, zafirlukast reduces the production of inflammatory mediators that are implicated in the pathogenesis of asthma. Zafirlukast is extensively hepatically metabolized by an enzyme called CYP2C9. Zafirlukast inhibits the action of CYP3A4, leading to drug–drug interactions with other drugs that are metabolized by CYP3A4. Genetic differences in LTC4 synthase and CYP2C9 may predict how a person reacts to zafirlukast treatment.

Zafirlukast (brand name Accolate) was the first cysteinyl leukotriene receptor antagonist approved in the United States. It is now approved in many other countries under other brand names.

Medical uses

Zafirlukast is FDA-approved for the prevention and treatment of asthma in adults and children older than 5 years old.[1] Like other leukotriene receptor antagonists, zafirlukast is thought to be useful for the long-term treatment of asthma, but it is generally less effective than inhaled glucocorticoids as monotherapy (which are the standard of care) or long-acting beta-2 agonists in combination therapy.[2] Notably, zafirlukast is ineffective in the event of an acute asthma attack.[1]

Available forms

There are two dosage forms for zafirlukast, notable for their age-adjustments. The 20 mg tablet is for adults and children older than age 12, whereas the 10 mg tablet is for children between the ages of 5 and 12.[1] Tablets should be stored at room temperature, out of direct sunlight, and away from sources of moisture.[1]

Tablets are for oral administration only.[1]

Pediatrics

As a general rule, leukotriene receptor antagonists like zafirlukast are more effective in children that are younger and whose asthma is less atopic.[3] Atopy refers to a predisposition towards developing allergic conditions, including asthma, hay fever, and eczema.[4]

Geriatrics

The hepatic clearance of zafirlukast is impaired in adults 65 years of age and older, resulting in a 2–3 fold increase in the maximum plasma concentration and the total area under the curve. Zafirlukast may increase the risk for infections (7.0% vs 2.9%, zafirlukast vs. placebo incidence respectively), especially lower respiratory tract infections, in older adults, though the infections noted were not severe.[1]

Pregnancy

Zafirlukast is considered to be "pregnancy category B." This is due, in part, to the wide safety margin of zafirlukast in animal studies investigating teratogenicity. No teratogenicity has been observed in doses up to 2000 mg/kg/day in cynomolgus monkeys, representing an equivalent 20x exposure of the maximum recommended daily oral dose in human adults. However, spontaneous abortions occurred in cynomolgus monkeys at 2000 mg/kg/day, though the dose itself was maternally toxic.[1]

Lactation

There is limited research on the use of zafirlukast in women whom are breastfeeding.[5] Based on data from the manufacturer, it is expected that 0.6% of the maternal weight-adjusted dose would reach a breastfed infant, though the effects in the infant are unknown.[5]

Renal impairment

Renal impairment does not appear to affect the pharmacokinetic profile of zafirlukast.[1]

Hepatic impairment

The hepatic clearance of zafirlukast is impaired by significant hepatic impairment. Cirrhosis of the liver can result in an increase in the maximum plasma concentration and the total area under the curve (a measure of drug exposure) by 50–60%.[1]

Contraindications

Zafirlukast is contraindicated in people that are hypersensitive or allergic to it.[1]

Adverse effects

Zafirlukast is generally well tolerated, though headache and gastrointestinal (GI) upset can occur. The incidence of headache is between 12 and 20%, which is similar to the incidence of headache found in patients taking placebos in the studies that lead to zafirlukast's approval. GI upset may include nausea, stomach discomfort/pain, and diarrhea. GI complaints can be lessened by taking zafirlukast with food, though this can dramatically impair the amount of drug that gets absorbed into the body (see the section on drug-food interactions below).[6]

Other common side effects include flu-like symptoms, sleep disturbances (abnormal dreams, insomnia), hallucinations, and daytime drowsiness.[6]

Neuropsychiatric effects

Neuropsychiatric side effects have been reported with the use of zafirlukast and other LTRAs. While some side effects are less severe (e.g. abnormal dreams), others are more serious (e.g. hallucinations, tremor, suicidality). These effects were discovered through post-marketing reports, as the initial trials were not designed to monitor for neuropsychiatric side effects.[7]

Hepatotoxicity

Zafirlukast can also cause rare but serious side effects like acute liver injury.[8] Zafirlukast-induced hepatotoxicity generally occurs within the first 2–6 months of initiating therapy, though cases have been reported up to 13 months after starting zafirlukast.[8] Zafirlukast-induced hepatotoxicity is characterized by a spectrum of liver damage symptoms, including fatigue, nausea, and right upper quadrant pain followed by dark urine, jaundice and pruritus.[8] Liver enzyme elevations are common, and the pattern usually reflects hepatocellular damage, resembling acute viral hepatitis.[8] It is unclear how the hepatotoxicity occurs, but it may be due to a metabolic intermediate of zafirlukast, since it is metabolized in the liver through the enzyme CYP2C9. When it does occur it can be fatal, and reexposure with zafirlukast may result in a worse injury.[8] Switching zafirlukast to another medication in the same class (e.g. montelukast) or in the related class of 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors can be attempted, but caution should be employed.[8]

According to the "Dear Health Care Provider" letter from AstraZeneca, zafirlukast-induced hepatotoxicity has occurred predominantly in females.[9]

Churg-Strauss syndrome

Several cases of Churg-Strauss syndrome, also known as allergic angiitis and granulomatosis, have been reported with the use of zafirlukast, montelukast, pranlukast, and other asthma medications.[10] When Churg-Strauss syndrome occurs, it tends to occur in people with long-standing asthma and sinus inflammation, chronic oral corticosteroid use, and the recent initiation of a new anti-asthma therapy (like zafirlukast) in conjunction with tapering the corticosteroids.[10] While the exact etiology of the development of Churg-Strauss symptoms in proximity to initiating zafirlukast is unknown, it is thought that withdrawal of chronic corticosteroids "unmasks" the previously undetected disease.[10] Because corticosteroid withdrawal often happens while starting a new anti-asthma medication (like zafirlukast), this explains the rare but notable association.[10] These cases may represent misdiagnosed asthma, as Churg-Strauss syndrome can induce symptoms of airway obstruction that are akin to an acute asthma exacerbation.[10] As these asthma-like symptoms are reduced by zafirlukast, the symptoms of Churg-Strauss (e.g. neuropathy) increase due to the lack of the broader, anti-inflammatory coverage that the steroid was providing.[10]

Overdose

The highest overdose reported with zafirlukast is 200 mg. All overdose patients have survived. Symptoms reported included rash and upset stomach.[1]

Interactions

Drug–drug interactions

Zafirlukast is an inhibitor of the hepatic drug-metabolizing enzyme cytochrome P450 family 3 subfamily A member 4 (CYP3A4).[1] Zafirlukast may increase the concentration of drugs that are metabolized through CYP3A4, such as the anticoagulant medication warfarin and the antiepileptic drugs phenytoin and carbamazepine.[1]

Drug-food interactions

The oral absorption (bioavailability) of zafirlukast is decreased by 40% when it is taken with high fat or high protein meals.[1] To avoid this interaction, zafirlukast should be taken on an empty stomach.[6] An empty stomach is classified as an hour before, or two hours after, consuming a meal.[1]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Zafirlukast is an antagonist of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 (CysLT1), a receptor found throughout the smooth muscle of the lungs, within interstitial lung macrophages (white blood cells that operate in the interstitial space of the lungs), and rarely in epithelial cells.[11] CystLT1 is a receptor for a specific class of leukotrienes that contain the amino acid cysteine.[2] These cysteinyl leukotrienes include leukotriene C4, leukotriene D4, and leukotriene E4, all of which are produced by inflammatory cells like eosinophils, basophils, and macrophages in the lungs.[2] Through their action on CysLT1 these leukotrienes can trigger bronchoconstriction, a state in which the bronchial passages of the lungs constrict,[12] leading to the characteristic, reactive airway symptoms associated with bronchial asthma.[2] The other pro-inflammatory effects of leukotrienes, such as their inhibition of mucus clearance and their stimulation of mucus secretion and edema, are thought to play a role in the characteristic symptoms of allergic rhinitis (also called hay fever[13]).[2] By inhibiting the action of these specific leukotrienes, zafirlukast is thought to exert an anti-inflammatory effect against leukotriene-mediated inflammatory conditions.[2]

Absorption

Zafirlukast is rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream following oral administration, reaching peak plasma levels within 3 hours of taking the dose.[1] The peak plasma level is the maximum concentration of zafirlukast in the blood.[14]

Distribution

Zafirlukast is moderately distributed into the body's tissues, with an apparent steady state volume of distribution of 70 liters.[1] Zafirlukast is highly plasma protein bound, 99% bound to albumin.[1] Albumin is the most abundant protein found in human plasma and is capable of carrying and transporting drugs (like zafirlukast) throughout the body.[15] In vivo research indicates that zafirlukast has low blood–brain barrier penetration.[1] The blood–brain barrier is a protective system that prevents many chemicals from entering the brain.[16]

Metabolism

Zafirlukast undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism into inactive metabolites.[1] Zafirlukast is primarily metabolized by the enzyme CYP2C9 to a hydroxylated metabolite.[1]

Elimination

Zafirlukast is primarily cleared through biliary excretion at a rate of 20 liters/hour. Zafirlukast is undetectable in urine. The mean terminal half-life ranges 8–16 hours, following linear kinetics up to doses of 80 mg.[1]

LTC4 synthase

Genetic polymorphisms in the LTC4 synthase promoter may predict response to zafirlukast. The single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) A444C (the wild-type DNA base adenine, at the 444th position on the gene, is mutated; cytosine is there instead), which is associated with a severe asthma phenotype, has been shown to decrease the clinical response to zafirlukast (both when the genetic alteration was heterozygous or homozygous).[17]

CYP2C9

Zafirlukast is metabolized through the hepatic enzyme CYP2C9. SNPs that decrease the function of CYP2C9 (such as CYP2C9*3 and CYP2C9*13) may decrease the hepatic clearance of zafirlukast, leading to increased exposure of zafirlukast.[18] Notably, the CYP2C9*3 polymorphism is more commonly encountered in people of south/central Asian ancestry (10.165%) compared to people of Caucasian (7.083%), African American (1.170%), African (1.033%), middle eastern (9.312%), and east Asian (3.365%) ancestry.[19]

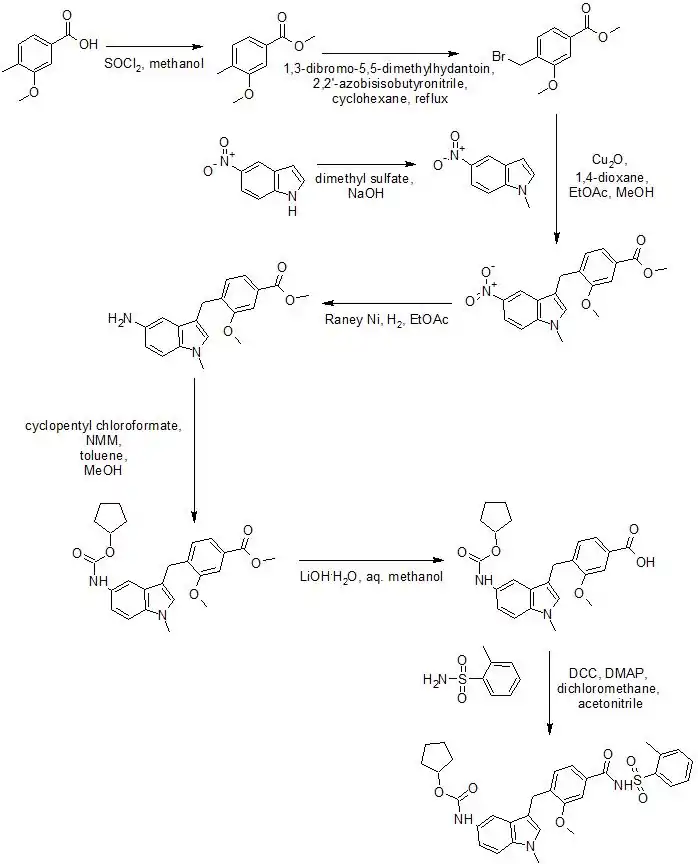

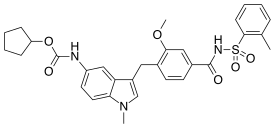

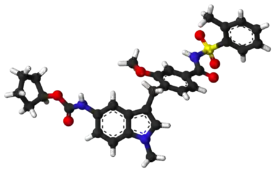

Chemistry

Physiochemical properties

Pure zafirlukast is described as a fine, white to pale yellow, amorphous powder. It is practically insoluble in water, slightly soluble in methanol, and freely soluble in tetrahydrofuran, dimethylsulfoxide, and acetone.[1]

History

Zafirlukast was the first cysteinyl leukotriene receptor antagonist approved in the United States.[10] Zafirlukast was approved in 1996.[10]

Society and culture

Economics

While preliminary evidence suggests that zafirlukast may reduce healthcare costs, the cost-effectiveness of using zafirlukast has not been established.[21]

Brand names

| A | Accolate, Accoleit, Aeronix |

| B | Benalucost |

| C | |

| D | |

| E | |

| F | Freesy |

| G | |

| H | |

| I | |

| J | |

| K | |

| L | |

| M | Monokast |

| N | |

| O | Olmoran |

| P | |

| Q | |

| R | |

| S | |

| T | |

| U | |

| V | Ventair |

| W | |

| X | |

| Y | |

| Z | Zafnil, Zalukast, Zukast |

Research

Mechanism of action

There is some research to suggest that zafirlukast actually acts as a partial inverse agonist at the CysLT1 receptor, though zafirlukast is still classified as an antagonist at this receptor. The possible clinical significance of this effect, if true, is unknown.[17]

Other indications

There is some evidence that suggests that zafirlukast may be beneficial in the treatment of chronic urticaria (hives), whether due to a known cause such as cold-exposure or due to an unknown cause (idiopathic).[17] A pilot study indicated that zafirlukast may be of some benefit in cystic fibrosis.[17] In the setting of chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD), a disease characterized by chronic inflammation of the lungs, zafirlukast has been shown to improve lung function.[17]

Veterinary use

Zafirlukast is sometimes used for the treatment of bronchial asthma in cats.[23]

References

- "ACCOLATE (zafirlukast) Package Insert" (PDF). www.accessdata.fda.gov. AstraZeneca LP. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- Mastalerz L, Kumik J (March 2010). "Antileukotriene drugs in the treatment of asthma". Polskie Archiwum Medycyny Wewnetrznej. 120 (3): 103–108. PMID 20332717.

- "Asthma in children". ClinicalKey. Elsevier BV. October 11, 2017.

- "Asthma, Hay Fever and Eczema: How to Cope with Atopic Triad". Inside Children's Blog. 29 April 2016. Archived from the original on 7 January 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- "Zafirlukast". Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. 2006. PMID 30000549. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Sorkness C, Schend V (2008). "Monitoring for Side Effects from Treatment". In Castro M, Kraft M (eds.). Clinical Asthma. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby. pp. 313–319. ISBN 978-0-323-04289-5.

- "Drug Safety Information for Heathcare [sic] Professionals – Updated Information on Leukotriene Inhibitors: Montelukast (marketed as Singulair), Zafirlukast (marketed as Accolate), and Zileuton (marketed as Zyflo and Zyflo CR)". Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- "Zafirlukast". LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. 2012. PMID 31643251. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Accolate (zafirlukast) – Labeling Changes". www.medscape.com. WebMD LLC. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- Wechsler ME, Pauwels R, Drazen JM (October 1999). "Leukotriene modifiers and Churg-Strauss syndrome: adverse effect or response to corticosteroid withdrawal?". Drug Safety. 21 (4): 241–251. doi:10.2165/00002018-199921040-00001. PMID 10514017. S2CID 8124340.

- Rovati GE, Capra V (September 2007). "Cysteinyl-leukotriene receptors and cellular signals". TheScientificWorldJournal. 7: 1375–1392. doi:10.1100/tsw.2007.185. PMC 5901261. PMID 17767356.

- "Medical Definition of Bronchoconstriction". www.merriam-webster.com. Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- "Medical Definition of Allergic Rhinitis". www.merriam-webster.com. Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- Valentine JL, Shyu WC, Grossman SJ (June 2010). "The Application of ADME Principles in Pharmaceutical Safety Assessment". In McQueen CA (ed.). Comprehensive Toxicology (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 123–136. ISBN 978-0-08-046884-6.

Cmax is the maximum concentration of the drug achieved in the plasma following dose administration and Tmax is the time at which Cmax is attained.

- "Plasma albumin". TheFreeDictionary.com. Saunders. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- de Vries HE, Kuiper J, de Boer AG, Van Berkel TJ, Breimer DD (June 1997). "The blood-brain barrier in neuroinflammatory diseases". Pharmacological Reviews. 49 (2): 143–155. PMID 9228664.

- Capra V, Thompson MD, Sala A, Cole DE, Folco G, Rovati GE (July 2007). "Cysteinyl-leukotrienes and their receptors in asthma and other inflammatory diseases: critical update and emerging trends". Medicinal Research Reviews. 27 (4): 469–527. doi:10.1002/med.20071. PMID 16894531. S2CID 24103280.

- "Clinical Annotation for CYP2C9*1CYP2C9*13CYP2C9*3 related to zafirlukast". PharmGKB. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- "CYP2C9 Allele Functionality Table". PharmGKB. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- Goverdhan G, Reddy AR, Himabindu V, Reddy GM (April 2014). "Synthesis and characterization of critical process related impurities of an asthma drug – Zafirlukast". Journal of Saudi Chemical Society. 18 (2): 129–138. doi:10.1016/j.jscs.2011.06.002.

- Dunn CJ, Goa KL (2001). "Zafirlukast: an update of its pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy in asthma". Drugs. 61 (2): 285–315. doi:10.2165/00003495-200161020-00012. PMID 11270943. S2CID 249894596.

- "Zafirlukast". Drugs.com. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- Byers CG, Dhupa N (June 2005). "Feline bronchial asthma: treatment" (PDF). Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 27 (6): 426–32.