Uriel Sebree

Uriel Sebree (February 20, 1848 – August 6, 1922) was a career officer in the United States Navy. He entered the Naval Academy during the Civil War and served until 1910, retiring as a rear admiral. He is best remembered for his two expeditions into the Arctic and for serving as acting governor of American Samoa. He was also commander-in-chief of the Pacific Fleet.

Uriel Sebree | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Rear Admiral Uriel Sebree | |

| Born | February 20, 1848 Fayette, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | August 6, 1922 (aged 74) Coronado, California, U.S. |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/ | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1863–1910 |

| Rank | Rear Admiral |

| Commands held | USC&GS Silliman USC&GS Thomas R. Gedney USS Pinta USS Wheeling (PG-14) USS Thetis USS Abarenda (AC-13) USS Wisconsin (BB-9) Commandant U.S. Naval Station Tutuila Pathfinder Squadron 2nd Division, U.S. Pacific Fleet Commander-in-Chief U.S. Pacific Fleet |

| Relations | Frank P. Sebree (brother) |

| Other work | Commandant (Acting governor) of Tutuila |

After graduating from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1867, Sebree was posted to a number of vessels before being assigned to a rescue mission to find the remaining crew of the missing Polaris expedition in the Navy's first mission to the Arctic. This attempt was only a partial success—the Polaris crew was rescued by a British ship rather than the US Navy—but this led to Sebree's selection eleven years later for a second expedition to the Arctic. That mission to rescue Adolphus Greely and the survivors of the Lady Franklin Bay expedition was a success. Sebree was subsequently appointed as the second acting governor of American Samoa. He served in this position for only a year before returning to the United States. In 1907, he was promoted to rear admiral and given command of the Pathfinder Expedition around the South American coast before being appointed commander of the 2nd Division of the Pacific Fleet and then commander-in-chief of the entire fleet. He retired in 1910 and died in Coronado, California, in 1922. Two geographical features in Alaska—Sebree Peak and Sebree Island—are named for Admiral Sebree.

Early life and career

Uriel Sebree was born in Fayette, Missouri, on February 20, 1848,[1] to Judge John Sebree, called "one of the prominent citizens of old Howard County" by the Jefferson County Tribune,[2] and his wife. Uriel was the first of two sons.[2] His brother, Frank Payne Sebree, became a lawyer. Uriel entered the United States Naval Academy on July 23, 1863, during the American Civil War. After his graduation in 1867, his first assignment was on board USS Canandaigua.[1] Over the next few years Sebree won repeated promotion: to ensign in 1868, master in 1870, and lieutenant in 1871. In 1873 he transferred to the ironclad USS Dictator.[1]

One episode in Sebree's early military history which influenced his later career was his participation in the second Polaris rescue mission. The Polaris expedition was an 1871 exploration of the Arctic that had aimed to reach the North Pole.[3]: 100 The expedition was troubled from the start: its leader, Charles Francis Hall, died in mysterious circumstances before the end of their first winter.[3]: 162–165 The following year, the Polaris remained trapped in ice and unable to return home. During a violent storm, the crew was separated into two groups: a small group of explorers was stranded on the now-crippled Polaris and the remainder were marooned on an ice floe.[3]: 198 These latter 19 survivors were discovered by chance and rescued by the civilian whaler USS Tigress.[3]: 326–331 Because of the Tigress's success, the Navy chartered the ship, temporarily rechristened her USS Tigress, and used her to launch a rescue attempt to locate the remainder of the crew. For this attempt the ship would be commanded by a group of eight navy officers, led by Captain James A. Greer, although much of the original civilian crew was retained. Lieutenant Sebree was one of the officers chosen for the mission.[4]

This rescue mission was the first official United States military expedition to the Arctic; previous expeditions, including that of the Polaris itself, had been led by civilians.[5] The Tigress sailed from New York on July 14, 1873,[4] traveling first to St. John's, Newfoundland and then to Godhavn and Upernavik in Greenland before following the coast further north. The crew searched North Star Bay, Northumberland Island, and Hartstene Bay before discovering the first sign of the Polaris crew: a camp on Littleton Island where they had wintered, now occupied by Inuit. The missing men, the rescuers were told, had constructed makeshift boats salvaged from their destroyed ship and traveled south. Acting on this clue, the Tigress searched the Baffin Island coast to Cumberland Sound, and then the Greenland coast from Ivigtut to Fiskenæsset and the Davis Strait, before returning to St. John's for fuel. Once there, they learned that the Polaris survivors had been rescued by a British ship and that their search was over.[6] After returning to New York the Tigress was transferred back to civilian use.[7]

| Midshipman – 1867 | |

|---|---|

| 1867–69 | USS Canandaigua |

| Ensign – 1868 | |

| Master – 1870 | |

| Lieutenant – 1871 | |

| 1872 | USS Saranac[8] |

| 1873 | USS Minnesota USS Dictator USS Tigress |

| 1873–76 | USS Franklin |

| 1878 | USC&GS A. D. Bache |

| 1879 | USC&GS Silliman |

| 1879–81 | USC&GS Thomas R. Gedney |

| 1882 | USS Brooklyn |

| 1883 | USS Pinta |

| 1884 | USS Powhatan |

| 1884 | USS Thetis |

| 1884–86 | United States Naval Academy |

| 1886–89 | U.S. Lighthouse Board Inspector, 13th District |

| 1889–92 | USS Baltimore |

| Lieutenant Commander – 1889 | |

| 1892–93 | 3rd Lighthouse District |

| 1893–96 | United States Naval Academy |

| 1896–98 | USS Wheeling (PG-14) |

| Commander – 1897 | |

| 1898–1901 | U.S. Lighthouse Board Inspector, 12th District |

| Captain – 1901 | |

| 1901–02 | USS Abarenda (AC-13) U.S. Naval Station Tutuila |

| 1902 | USS Wheeling |

| 1903–04 | USS Wisconsin (BB-9) |

| 1904–07 | Naval War College U.S. Lighthouse Board |

| Rear Admiral – 1907 | |

| 1907–08 | Pathfinder Squadron |

| 1908–09 | United States Pacific Fleet, 2nd Division |

| 1909–10 | United States Pacific Fleet |

After this expedition, Sebree was assigned to the screw frigate USS Franklin where he remained for three years.[1] In 1878, he was assigned to work with the United States Coast Survey on board the A. D. Bache. The following year he was given his first two commands: the Silliman and then the Thomas R. Gedney, both ships of the United States Coast Survey. He remained on the latter ship for nearly three years before being assigned to USS Brooklyn in 1882.[1] In 1883, he was given his first command of a Navy ship, USS Pinta, with orders to sail to Alaska.[9]

Court martial

On October 3, 1883, prior to leaving for Alaska, the Pinta collided with the civilian brig Tally Ho off the coast of Nantucket.[10] Sebree was not held directly responsible for the collision, as he was below deck at the time, but it was alleged that he did not do enough to determine whether the other ship was damaged before sailing away.[11] Charges were brought against him in November and in December he was found guilty of "culpable negligence and inefficiency in the performance of his duty".[12] He was sentenced to be suspended from rank and duty for three years with an official reprimand from the Secretary of the Navy.[13] Believing the sentence to be too harsh, Secretary William E. Chandler reduced it to a public reprimand only.[14] Sebree was subsequently transferred to USS Powhatan, although not as the ship's commanding officer.[1]

Greely Relief Expedition

One month after joining the Powhatan, Sebree was transferred again, this time to serve as the executive officer of USS Thetis for another trip into the Arctic.[15]: 123 In 1881, Army Lieutenant Adolphus Greely had left on an expedition to establish a base at Lady Franklin Bay on northern Ellesmere Island (now part of the Canadian territory of Nunavut). Greely was left with provisions for three years but was to expect supply ships in 1882 and 1883.[15]: 22 Both attempts to resupply the expedition failed and, with Greely's provisions running low, the Navy prepared an expedition in early 1884 to attempt a resupply or rescue. The expedition was led by Captain Winfield Scott Schley and consisted of lead ship USS Thetis (with Sebree as the executive officer and navigator), USS Bear, and the borrowed HMS Alert. Many of the officers, including Sebree, were selected for their previous Arctic experience.[15]: 118–125 The Thetis left New York on May 1, 1884, and the group slowly progressed through the ice of Melville Bay, chasing clues and records left by the expedition, to finally discover the survivors of Greely's camp off Cape Sabine on June 22, 1885. Of the 25 members of the expedition, only 6 survived (one more died on the return journey).[15]: 223 The expedition sailed first for Upernavik, Greenland, arriving on July 2, 1884, and then made its way back to the United States, landing at Portsmouth, New Hampshire on August 1, 1884. Schley later reported that a delay of just two more days would have been fatal to the remaining six members of the expedition.[15]: 257–272 Sebree and the other members of the relief expedition gained fame from the voyage. Even ten years later, in 1895, a report by The New York Times celebrating the 50th anniversary of the United States Naval Academy listed Sebree as one of the most "famous" graduates, despite his relatively low rank.[16]

After his return from the expedition Sebree taught at the Naval Academy for two years before being transferred to the 13th Lighthouse District, to serve as the lighthouse inspector for Oregon and Washington Territory. While stationed there he was promoted to lieutenant commander in March 1889.[1][17]

Valparaíso riots

In September 1889 he was made the executive officer of USS Baltimore,[18] again under Captain Schley. Both men were still serving aboard the Baltimore when its sailors were attacked in Valparaiso, Chile in October 1891, and gave testimony toward the events during the later investigation.[19]

From September 1892 to July 1893, Sebree served as assistant to the inspector of the 3rd Lighthouse District.[20][21]

Sebree taught at the Academy from 1893 to 1896.[1] At the end of his time there, he was briefly given command of USS Wheeling (PG-14) before being put in command of the Thetis, which was doing survey work off the coast of California.[22] In 1897 he was promoted to commander.[23] During the Spanish–American War, Sebree again commanded the Wheeling in the Pacific for the duration of the war.[24] His assignment was to patrol the coast of Alaska and the Aleutian Islands, far from both the Caribbean and Pacific theaters of the war, and he saw no significant action.[25] After the war, he was transferred to the 12th Lighthouse District as an inspector.[26]

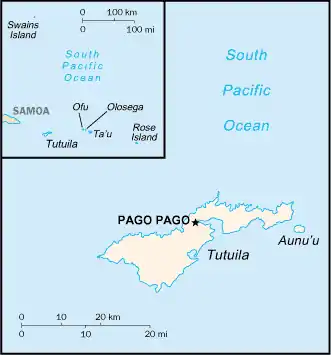

American Samoa

On October 9, 1901, Sebree was promoted to captain and received orders to travel to American Samoa to take command of USS Abarenda (AC-13) and to be commandant of the United States Naval Station Tutuila.[27] Three days later, he was promoted to captain.[28] At this time the commandant of the naval station was considered the acting governor of the territory as Congress had not yet formalized the U.S. Navy's role there. Sebree was the replacement for Commandant Benjamin Franklin Tilley, who had recently had charges brought against him for immorality and drunkenness. While Sebree was in transit to the islands, Tilley was tried and acquitted of the charges against him but the decision to replace him was not changed.[29]: 139 Captain Sebree arrived in Samoa and took up his new post on November 27, 1901.[30]

Acting governor

Unlike Tilley, who had been the first acting governor of the territory, Sebree was very concerned about his legal status. Officially, he was only commandant of the naval station then under construction, although the deed of cession of the territory acknowledged his theoretical authority to govern the people. He was concerned that lawsuits could be brought against him or future acting governors until the situation was clarified and made official by the United States government.[29]: 150–153 To this end, he made a recommendation to the United States Congress to assemble a panel to consider the territory's status and requested that an Assistant Secretary of the Navy come to the territory to meet with him. Both requests were refused.[29]: 150–153 A further example of this ambiguity came in March 1902, when Sebree received orders to give up command of the Abarenda to give him additional time as commandant and "governor".[31] To these orders, he responded that he still had not been officially made "governor" and that, if he were to act as a governor, he should be given the proper credentials and legal authority to do so.[29]: 150–153 The Navy did not respond directly to Sebree's request, but he was given command of USS Wheeling three months later.[32]

Despite his protests, Sebree did act as the governor of the territory. During his administration, the United States Congress approved $35,000 to pay off debts related to construction costs for the naval station, and planning began for the construction of a lighthouse on Aunu'u. The Fita Fita Guard, the local militia that Tilley had organized, continued its training, and Sebree arranged to train some members of the force as a military-style brass band. Sebree also attempted to improve local agriculture and even petitioned the Department of Agriculture for assistance, but was turned down.[29]: 150–153

Petition for civilian government

Tensions escalated between foreign traders on Samoa and the local populace, due in part to controls which Tilley had put in place to protect Samoan farmers from exploitation.[29]: 150–153 Dr. David Starr Jordan, a prominent American biologist doing research in the territory, was so concerned by these tensions that he sent a letter to President Theodore Roosevelt asking that a trader not be made governor of the territory, if a civil administration were created. Shortly after, many traders and locals, including a Samoan tax collector, circulated a petition requesting a change in the way the copra crop was taxed and asking for the Navy to cease governing the territory. The petition was sent to members of Congress and the cause was picked up by California representative Julius Kahn and gathered significant press coverage. This movement eventually reached President Roosevelt; his decision was not to act on the petition.[29]: 150–153

On December 16, 1902, Sebree was granted a leave of absence to return to the United States and care for his wife who had been badly hurt in a fall.[33] In his place, Lieutenant Commander Henry Minett, Sebree's executive officer, was made acting commandant of the station and therefore acting governor of the territory. He was also given command of the Wheeling. Captain Edmund Beardsley Underwood was selected as Sebree's replacement, but that decision was not made official immediately, and Underwood remained in Washington to consult with Sebree and President Roosevelt on the governance of the territory. Underwood's selection was not announced until May 1903.[34]

Later career

Following his wife's recovery, Sebree returned to service and was given command of USS Wisconsin (BB-9) on February 11, 1903. The Wisconsin was the flagship of the North Squadron of the Pacific fleet under Robley D. Evans.[35] While under Sebree's command, the Wisconsin and her crew were evaluated as one of the best, according to annual targeting exercises.[36]

Nicholson court-martial

In the late summer of 1903, Paymaster Rishworth Nicholson of USS Don Juan de Austria assaulted a German Consul at a ball in Yantai, China. He was promptly brought up on charges of "drunkenness", "scandalous conduct tending to the destruction of good morals", and "falsehood" and taken to the Wisconsin for his court martial.[37] Sebree and a group of six other officers found him guilty of the first charge, guilty of a lesser offense for the second charge, and not guilty on the third. His sentence was determined to be a reduction in grade equivalent to one year of seniority. Three of the officers, not including Sebree, wrote a supplementary opinion requesting clemency for Nicholson.[38]

However, Rear Admiral Evans, the commander of the Asiatic Squadron, rejected the verdict as inadequate and requested that the court reconsider the decision. The court reconvened and returned the same judgment and sentence. In response, Evans wrote a scathing critique of the process, calling it a "travesty of justice" and stating that Nicholson's actions were "less reprehensible than his judges".[37] This critical essay was required to be posted at every naval base and on every ship in the Pacific and was reprinted in full by The New York Times and other civilian newspapers. Evans banned the three officers who had publicly requested clemency from participating in future courts martial. Press reports questioned whether Evans had that authority as the military justice system was intended to be impartial.[37] In late September 1903, the three officers who had been named in the critique filed a protest with Secretary of the Navy William Henry Moody stating that Admiral Evans had overstepped his authority by publicly reprimanding them without a court martial and that charges should be brought against him. On November 18, 1903, Moody denied the petition and the sentences were left to stand.[39]

During this controversy, Sebree remained silent on the issue, and it is unknown whether he was a member of the majority or not. Evans commented in his critique that he was unsure who the other supporters of the majority decision were. As criticism swirled around the trial itself, the editors of the magazine United Service defended Sebree and stated that he had "universal esteem throughout the Navy service" and that he had a "large experience, sound judgment, even temper and most excellent record".[40] Following this announcement, Sebree was transferred to the Naval War College in Rhode Island to work as an instructor and as Secretary of the Lighthouse Board.[41][42]

Lightship No. 58 incident

In December 1905, a storm and mechanical failures caused major problems for the crew of the lightvessel Lightship No. 58 anchored off of Nantucket. Her crew, led by Captain James Jorgensen, fought for two days to prevent the vessel from foundering, but were ultimately unsuccessful. They were rescued by Captain Gibbs of the Azalea.[43] The fallout over this incident caused enough of a stir that the military had to respond to it directly. Under Navy rules, the eleven officers and crew members of the No. 58 were denied pay while they were recovering from their injuries and until they were posted to new vessels under a regulation that prohibited pay to sailors whose ships had sunk. The sailors appealed to Sebree, as Secretary of the Lighthouse Board, but he did not or could not accommodate them. Instead, the officers were given commendations by Secretary Victor H. Metcalf and "preference in future appointments".[43] Admiral Dewey and Captain Sebree made a second recommendation, which was approved, that Captain Gibbs receive a commendation and a pay increase for his service.[44]

Pathfinder Squadron

Sebree was promoted to rear admiral in 1907 and was given command of a squadron of two ships: his flagship, USS Tennessee, and USS Washington.[45] This so-called "Pathfinder Squadron" would travel from New York to California via Cape Horn. This mission allowed the Navy to show off two of its newest cruisers to South American governments as well as transfer ships to the Pacific Fleet in what was seen as an example of American gunboat diplomacy. Along the way, Sebree had formal meetings with Brazilian President Afonso Pena,[46] Peruvian President José Pardo y Barreda, and United States diplomatic staff in both countries.[47] He also met with representatives in Chile and other countries.[48] When the squadron finally arrived in California, it was joined by USS California and participated in public-relations events at West Coast ports.[49] The diplomatic mission over, the Pathfinder Squadron, with the California and others, became the 2nd division of the United States Pacific Fleet, with Sebree remaining in command. Rear Admiral William T. Swinburne was placed in command of the full fleet.[50]

On June 5, 1908, Sebree was nearly killed during a speed trial of the Tennessee off the coast of California. He had just completed a tour of the starboard boiler room when a steam pipe burst, instantly killing two officers and wounding ten others, three fatally. Witnesses reported that Sebree and other officers had left the boiler room only 50 seconds earlier.[51]

In August 1908, the full Pacific Fleet was dispatched to numerous ports in the Pacific Ocean on a diplomatic mission similar to the one undertaken by Sebree in South America the previous year.[52] On this voyage, Sebree and Swinburne met with leaders and representatives from the Territory of Hawaii,[53] the Philippines,[54] Western Samoa,[55] and Panama.[56] While visiting the Western Samoan capital of Apia, Sebree was presented with a souvenir album of Samoan scenery in honor of his time as governor of neighboring American Samoa.[55]

Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet

On April 15, 1909, Admiral Swinburne, the commander-in-chief of the Pacific Fleet, announced his retirement, and Sebree was appointed to replace him on May 17.[57] Good public relations remained a major goal of the fleet, and in June, the fleet was displayed at the Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition. President William Howard Taft led the exposition's opening ceremony, and many American dignitaries were in attendance.[58]

Sebree's final mission before his retirement saw him lead the Pacific Fleet on a tour of ports in east Asia. The fleet left San Francisco on September 5, 1909, sailing west to the Philippines, with only brief stops en route.[59] Speed testing was a major goal of the early part of the voyage and he and his fleet of eight ships broke speed records by sailing to Honolulu in just over four days. Six of the eight ships were able to make the voyage in that time; the Colorado and West Virginia had mechanical failures which prevented them from completing the voyage on time. On the Colorado, those failures led to the deaths of two crewmen due to a steam pipe explosion.[60] From Hawaii, the fleet moved on to Manila where the ships performed target practices and exercises, as well as being cleaned and repainted, before resuming their primary mission by sailing to Yokohama, Japan. In Japan, the fleet dispersed and small groups of cruisers were dispatched to the ports of British-controlled Hong Kong, Wusong in China, and Kobe, Japan. Afterwards, the fleet returned home.[59] Just before Sebree's retirement the Pacific Fleet was split into two: a smaller Pacific Fleet and an Asiatic Fleet commanded by Rear Admiral John Hubbard.[61] On February 19, 1910, Sebree officially retired and was replaced as head of the Pacific Fleet by Rear Admiral Giles B. Harber.[62]

Shortly after retiring, Sebree was given a farewell banquet which included British Field Marshal Herbert Kitchener as a notable guest and California Governor James Gillett as toastmaster.[63] In retirement, Sebree continued to attend Navy functions. In 1916, Sebree reported that the United States Navy lagged behind the world's other major navies. A single dreadnought, he claimed, could ravage the entire Pacific Fleet which was at that time relying on submarines for defense.[64] The Atlantic Fleet already had dreadnoughts in commission.[65]

Sebree died at his home in Coronado, California on August 6, 1922. He and his wife, Anne Bridgman Sebree, are buried in Arlington National Cemetery. They had one son, John Bridgman Sebree (1889–1948), who served in the United States Marine Corps.[66]

Honors and awards

Sebree Peak[67] and Sebree Island,[68] both in Alaska, are named for the admiral.

References

- Hamersly, Lewis Randolph (1898). The Records of Living Officers of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps (6th ed.). New York: L. R. Hamersly.

- "Missourians Meet in Africa". The Atlanta Constitution. 1898-04-23. p. 7. (reprinted from the Jefferson County Tribune)

- Blake, E. Vale (1874). Arctic Experience. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- "Departure of the Tigress". The New York Times. 1883-07-15. p. 8.

- "Another Arctic Expedition Begun". Scientific American. Vol. 29, no. 5. 1973-08-02. p. 64.

- Dieck, Herman (1885). The Marvellous Wonders of the Polar World. National Publishing Company. pp. 109–112.

- "Tigress". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 2015-06-09.

- "The "Saranac"". Daily Alta California. No. Volume XXIV, Number 8277. November 24, 1872. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- "Pinta Ordered to Sea". Washington Post. 1883-06-14. p. 4.

- "Inquiring Into a Collision". The New York Times. 1883-10-27. p. 8.

- "Two Naval Officers Reprimanded". The New York Times. 1883-12-28. p. 3.

- "Court-Martial Sentences and Orders to Officers". The New York Times. 1883-12-15. p. 3.

- "Army and Navy Matters". The New York Times. 1883-11-17. p. 3.

- "Army and Navy News". The New York Times. 1883-12-22. p. 3.

- Schley, Winfield Scott; Soley, J. R. (1885). The Rescue of Greely. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- "Fifty Years of the Nation's Naval Academy". The New York Times. 1895-10-06. p. 20.

- "Navy Gazette". Army and Navy Journal: 965. July 20, 1889. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Navy Gazette". Army and Navy Journal: 65. September 21, 1889. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Grave Difficulties: the Chilean Situation has an Ugly Aspect". Los Angeles Herald. Los Angeles, California. January 14, 1892. p. 1. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Navy Gazette". Army and Navy Journal: 23. September 3, 1892. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Navy Gazette". Army and Navy Journal: 747. July 1, 1893. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "The Thetis Arrives". Los Angeles Times. 1896-10-04. p. 29.

- "North Carolina District Judge Named". Washington Post. 1897-02-26. p. 4.

- Chadwick, French Ensor (1911). The Relations of the United States and Spain: The Spanish–American War. C. Scribner's Sons. p. 398.

- "U.S.S. Wheeling, Gunboat No. 14". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 2015-06-09.

- "The United Service". The New York Times. 1898-10-21. p. 4.

- "The United Service". The New York Times. 1901-10-09. p. 5.

- "Orders to Naval Officers". Washington Post. 1901-12-25. p. 3.

- Gray, J. A. C. (1960). Amerika Samoa: History Of American Samoa And Its United States Naval Administration. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 978-0-87021-074-7.

- "Sebree Takes Up Reigns of Government". Los Angeles Times. 1901-12-17. p. A4.

- "The United Service". The New York Times. 1902-03-01. p. 3.

- "Public Buildings Bill". Los Angeles Times. 1902-06-07. p. 4.

- "Sparks from the Wires". Atlanta Constitution. 1902-12-31. p. 7.

- "Greetings from Samoa". Washington Post. 1903-01-22. p. 4.

- "Orders to Naval Officers". Washington Post. 1903-01-07. p. 5.

- "Navy's Target Competition". The New York Times. 1905-07-09. p. 6.

- "Naval Court Denounced". The New York Times. 1903-09-22. p. 3.

- "Demoralizing the Navy". The Independent. Vol. 55, no. 2861. October 1903. pp. 2360–2361.

- "Admiral Evans Upheld for Censure of Court". The New York Times. 1903-11-19. p. 1.

- "Service Salad". United Service. 4 (4): 426. October 1903.

- "The United Service". The New York Times. 1904-05-14. p. 13.

- Bureau of Naval Personnel (1906). Register of Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy and Marine Corps and Reserve Officers on Active Duty. Washington DC: Government Printing Office. p. 8. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Sailors Saved; Lose Jobs". Chicago Tribune. 1905-12-14. p. 6.

- "Navy Recognizes Bravery". The Washington Post. 1905-12-27. p. 4.

- "Cruisers' Trip to the Pacific". Washington Post. 1907-10-02. p. 11.

- "Cruisers at Rio de Janeiro". Washington Post. 1907-11-06. p. 4.

- "Admiral Sebree Visits Callao". Washington Post. 1907-12-07. p. 4.

- "Pathfinders of Navy Stop at Many Ports". Los Angeles Times. 1908-01-14. p. II14.

- "Open All Three For Visitors". Los Angeles Times. 1908-03-24. p. II8.

- Johnson, Robert Erwin (1980). Thence Round Cape Horn. Ayer Publishing. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-405-13040-3.

- "Explosion Kills Four on Cruiser". Washington Post. 1908-06-06. p. 1.

- "Pacific Fleet Sails Away to South Seas". Los Angeles Times. 1908-08-25. p. I2.

- "Rear-Admirals Dined". Los Angeles Times. 1908-09-07. p. I1.

- "Scare Won't Stop Fleet". The New York Times. 1908-09-23. p. 4.

- "Pacific Fleet at Apia". The New York Times. 1908-09-21. p. 3.

- "Cruisers at Panama". The New York Times. 1908-12-14. p. 4.

- "Sebree for Pacific Fleet". Los Angeles Times. 1909-04-16. p. I5.

- "Alaska-Yukon Opened By Taft". Atlanta Constitution. 1909-06-02. p. 2.

- "Big Cruiser Fleet for East". The New York Times. 1909-08-02. p. 4.

- "Pacific Fleet Breaks Record". Los Angeles Times. 1909-09-11. p. I5.

- "Hubbard Heads Asiatic Fleet". Atlanta Constitution. 1910-01-01. p. 2.

- "Admiral Sebree Retires". Atlanta Constitution. 1910-02-20. p. B3.

- "Kitchener is Noted Guest". Los Angeles Times. 1910-04-08. p. I4.

- "One Dreadnought Could Whip Fleet". Los Angeles Times. 1916-04-06. p. II2.

- "USS Michigan (Battleship # 27, later BB-27)". Naval Historical Center. p. 159. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- "Births, Marriages and Deaths". Army and Navy Register. 72. 1922-08-12.

- Baker, Marcus (1906). Geographic Dictionary of Alaska (PDF) (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. p. 559.

- Orth, Donald J (1967). Dictionary of Alaska Place Names. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. p. 849. Archived from the original on 2015-10-02.

Further reading

- Blake, E. Vale (1874). Arctic Experience. New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 978-0-8154-1189-5.

- Clare, Israel Smith (1898). Unrivaled History of the World. Vol. 5. Chicago: The Werner Company. pp. 1860–1861.

- Chadwick, French Ensor (1911). The Relations of the United States and Spain: The Spanish–American War. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Dieck, Herman (1885). The Marvellous Wonders of the Polar World. Philadelphia, Chicago, and St. Louis: National Publishing Company.

- Gray, J. A. C. (1960). Amerika Samoa: History Of American Samoa And Its United States Naval Administration. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 978-0-87021-074-7.

- Johnson, Robert Erwin (1980). Thence Round Cape Horn (Reprint ed.). Ayer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-405-13040-3.

- Schley, Winfield Scott (September 1904). Forty-five Years Under the Flag. New York: D. Appleton and Company. ISBN 978-0-548-23465-5.

- Schley, Winfield Scott; Soley, J. R. (1885). The Rescue of Greely. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.