Typhoon Omar

Typhoon Omar of 1992, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Lusing,[1] was the strongest and costliest typhoon to strike Guam since Typhoon Pamela in 1976. The cyclone formed on August 23 from the monsoon trough across the western Pacific Ocean. Moving westward, Omar slowly intensified into a tropical storm, although another tropical cyclone nearby initially impeded further strengthening. After the two storms became more distant, Omar quickly strengthened into a powerful typhoon. On August 28, it made landfall on Guam with winds of 195 km/h (120 mph). The typhoon reached its peak intensity the next day, with estimated 1‑minute winds of 240 km/h (150 mph), making it a "super typhoon" according to the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC).[nb 1] Omar weakened significantly before striking eastern Taiwan on September 4, proceeding into eastern China the next day and dissipating on September 9.

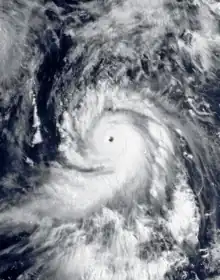

Omar over the Pacific Ocean at peak intensity on August 29 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 23, 1992 |

| Dissipated | September 9, 1992 |

| Very strong typhoon | |

| 10-minute sustained (JMA) | |

| Highest winds | 185 km/h (115 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 920 hPa (mbar); 27.17 inHg |

| Category 4-equivalent tropical cyclone | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/JTWC) | |

| Highest winds | 240 km/h (150 mph) |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 15 |

| Damage | $561 million (1991 USD) |

| Areas affected | Guam, Philippines, Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan, China, Vietnam |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1992 Pacific typhoon season | |

On Guam, Omar caused one death and $457 million (1992 USD) in damage.[nb 2] Strong gusts up to 248 km/h (154 mph) left nearly the entire island without power for several days. The outages disrupted the water system and prevented the island-based JTWC from issuing advisories for 11 days. Omar damaged or destroyed 2,158 houses, leaving 3,000 people homeless. In response to the destruction, the island's building codes were updated to withstand winds of 250 km/h (155 mph), and insurance companies discontinued new policies for structures not made of concrete. While passing well north of the Philippines, the typhoon killed 11 people and wrought ₱903 million ($35.4 million) worth of damage to 538 houses. Omar then brushed the southern islands of Japan with strong gusts and light rainfall, causing ¥476 million JPY (US$3.8 million) in crop losses. In Taiwan, scattered flooding caused three deaths and $65 million in damage, mostly to agriculture.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

Typhoon Omar originated from a tropical disturbance that was first noted on August 20 over the open Pacific Ocean, which exhibited persistent convection, or thunderstorms. During this early phase, two tropical cyclones dissipated and another became extratropical across the western Pacific basin; this caused the monsoon trough, which spawned most of the storms in the basin, to realign in a more climatologically appropriate manner.[2] According to the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), Omar developed into a tropical depression at 1800 UTC on August 23.[4] The Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) assessed a slower pace of strengthening, issuing a tropical cyclone formation alert at 2100 UTC before initiating advisories on Tropical Depression 15W on August 24.[2]

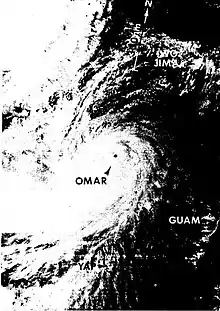

As the depression traveled generally westward, the JTWC upgraded it to Tropical Storm Omar on August 25,[2] and the JMA followed suit on the next day.[4] Omar began to slow as it tracked westward. Outflow from nearby Tropical Storm Polly to the west produced a stream of strong wind shear over Omar, slowing intensification. The JTWC noted that the shear could decouple Omar's wind circulation from its convection, possibly weakening the storm. However, as Omar and Polly moved farther apart, a high-pressure ridge developed between the storms. This caused Omar to drift northward and then west-northwestward into a region with decreased shear, which allowed it to resume strengthening. Early on August 27, the JTWC upgraded the system to a typhoon, and an eye began to appear around 23:00 UTC that day.[5] Omar entered a phase of rapid intensification on August 28,[2] at which point the JMA also classified it as a typhoon.[4] The typhoon made landfall on Guam soon after, with 1‑minute sustained winds of about 195 km/h (120 mph).[2] The eye, 37 km (23 mi) in diameter,[2] slowly crossed the northern portion of the small island over a period of 2.5 hours.[5]

At 1800 UTC on August 29, Omar reached its peak intensity with 10‑minute sustained winds of 185 km/h (115 mph) and a minimum barometric pressure of 920 mbar (hPa; 27.17 inHg) as estimated by the JMA; this intensity was maintained for 24 hours before a steady weakening trend began.[4] The JTWC estimated higher 1‑minute winds of around 240 km/h (150 mph), making Omar a super typhoon.[2] Two days later, the typhoon came close enough to the Philippines to warrant monitoring from PAGASA,[nb 3] who named the storm Lusing.[1] By 1500 UTC on September 3, the JMA downgraded Omar to a tropical storm,[4] although the JTWC maintained its typhoon intensity through the next day.[2] Heading generally westward, the storm made landfall on the east coast of Taiwan near Hualien City on September 4.[6] After traversing the island in seven hours, Omar exited the coast of Yunlin County and emerged into the Taiwan Strait.[7] The storm crossed the body of water and moved ashore in eastern China near Xiamen, Fujian, on September 5.[6] Inland, Omar quickly degenerated into a tropical depression before turning west-southwest. It proceeded across southern China while heavily weakening, and completely dissipated over northern Vietnam on September 9.[4]

Preparations and impact

Guam

Ahead of the storm on August 25, the United States Department of Defense set the Condition of Readiness (COR) at stage 3 on Guam, indicating destructive winds were possible within 48 hours. A day later, the COR was raised to stage 2; all but two United States Navy ships were sortied from the harbor to prevent damage, and the remainder rode out the storm southwest of Guam.[9] On August 28, COR 1 was declared, the highest level. In response, all fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters on the island were moved into hangars or transported to Japan or the Philippines.[9] All schools were closed for the duration of Omar's passage over Guam.[10] Flight operations were suspended for at least two days,[11] stranding 5,000 passengers on the island. About 3,100 people rode out the storm in emergency shelters.[12]

Omar was the strongest and most damaging typhoon to hit Guam since Typhoon Pamela in 1976.[2][5] The typhoon was felt on all parts of Guam;[13] tropical-storm-force winds affected the island for 16 hours,[2] and wind gusts were estimated to have reached 248 km/h (154 mph) in areas beneath the western eyewall.[5] However, the high winds caused the anemometer at Hagåtña to fail during the eye's passage, and the radar at Andersen Air Force Base was lost,[2] preventing accurate wind speed assessments. The lowest barometric pressure was 940 mbar (27.76 inHg) at Apra Harbor. Omar's slow movement resulted in prolonged heavy rainfall, peaking at 519 mm (20.44 in) at the Guam National Weather Service Office in Tiyan and reaching 417 mm (16.41 in) at Andersen AFB.[5][14]

Damage on Guam was heaviest from the central region to the northern coast, in particular to tourist areas and military bases.[11][15] The Naval Computer and Telecommunications Area Master Station was shut down due to power outages and water damage to the generators. Two US Navy ships, the USS Niagara Falls (AFS-3) and the USS White Plains (AFS-4)—both naval supply ships—went aground due to rough seas and strong winds,[16] and the dry dock at Apra Harbor was washed ashore. Omar destroyed dozens of businesses on the island.[17] High winds knocked a crane into an apartment building[18] and downed 400 wooden and 20 concrete power poles across Tumon,[2] leaving 70% of the island without power.[16] Throughout Guam, Omar disrupted transportation and communication systems, and led to the failure of water pumping systems.[2] Landslides covered roads, and low-lying areas were flooded.[11] About 2,000 homes were destroyed and another 2,200 were damaged to varying degrees,[12] displacing nearly 3,000 people.[2] Destruction was heaviest to wooden structures; buildings made of concrete fared relatively well during the storm. Island-wide, damage totaled $457 million,[2] split nearly evenly between the military bases and civilian damage.[17] One person died on Guam, and more than 200 people required emergency treatment[2]—including about 80 injured by flying debris.[15]

Elsewhere

While over the open Pacific Ocean, Omar passed well northeast of the Philippines just days after Tropical Storm Polly caused flooding and deaths in the country. The nation's chief weather specialist noted that Omar was "more powerful than Polly and [able to] induce monsoon rains over a wide area."[19] Omar ultimately affected northern Luzon, primarily the Cordillera Administrative Region, Ilocos Region, and the Cagayan Valley.[20] Across the country, the storm killed 11 people.[1] The typhoon destroyed 393 houses and damaged another 145,[20] leaving 1,965 people homeless.[1] Damage was estimated at ₱903 million ($35.4 million),[nb 4] much of it to agriculture.[20]

After its destructive landfall in Guam, Omar struck Wuqi District in Taiwan with maximum winds of 78 km/h (49 mph).[2][22] The worst effects in the country were from widespread rain; the strongest rainfall rates remained concentrated in southern regions, peaking at 375.4 mm (14.78 in) in Kaohsiung.[7][22] The storm flooded five counties and left 766,000 people without power. High waves washed ashore four ships in Kaohsiung,[6] and farmland and fisheries there, as well as in Yunlin, Chiayi City, and Pingtung County, suffered heavy damage.[7] Throughout Taiwan, Omar resulted in three deaths (two of which drownings), twelve injuries, and more than $65 million (USD) in damage.[2][22]

The fringes of the typhoon dropped light rainfall in the outer regions of Japan, peaking at 28 mm (1.1 in) on Iriomote-jima. The highest wind gust was 72 km/h (45 mph) on Yonaguni.[23] Omar damaged the sugar cane and okra in the southern Japanese islands, leading to crop losses of ¥476 million JPY (US$3.8 million).[nb 5] In addition, traffic was disrupted and 38 flights were canceled.[25] Later, Omar spread rainfall along its path through southern China, flooding parts of northwestern Hong Kong on September 7.[2][6]

Aftermath

Immediately after Omar's landfall in Guam, former Governor Joseph Franklin Ada declared a state of emergency,[26] and former U.S. President George H. W. Bush declared the island a federal disaster area.[27] In the wake of the storm, several people were arrested for looting.[15] The Federal Emergency Management Agency opened up disaster assistance centers where residents were able to apply for federal aid; it ultimately provided about $18.4 million in assistance, including disaster housing, storm-related unemployment benefits, and grant programs for families or businesses,[28] helping over 11,000 people.[17] The federal government paid for 100% of the debris removal, emergency work, and reconstruction of uninsured public buildings, although it usually only provides 75% of the cost for typical disasters. This was due to the sequence of three significant tropical cyclones affecting the United States in three weeks; in addition to Omar, Hurricane Andrew struck Florida in August and Hurricane Iniki hit Hawaii in September. The Department of Defense assisted the affected areas with 27 members of the Guam National Guard and 700 members of the military. The military provided temporary housing, generators, and construction supplies, at a cost of $5.75 million, though most of the disaster needs were handled by the government.[16] The local Red Cross provided $6 million in assistance after the storm.[28] Due to the combined damages from Andrew, Iniki, and Omar, the United States Congress passed the Dire Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act, 1992, which provided additional funding for the agencies responding to the disasters through the fiscal year ending on September 30.[29]

For 11 days, the JTWC on Guam was unable to continue operations, relying on a backup agency. The damage to the airport radar prompted the NEXRAD—a network of high-resolution weather radars—to be installed earlier than scheduled, in February 1993,[2] and limited incoming and outgoing flights to the daytime.[12] On August 30, a naval ship docked at Apra Harbor to provide a temporary mobile radar. By September 15, both ships that had been washed ashore were refloated. In the aftermath of the destruction, insurance companies decided to stop issuing new policies for structures not made of concrete.[28] In January 1996, former Governor Carl Gutierrez issued an executive order, mandating that homes or storm shutters on the island withstand winds of at least 250 m/h (155 mph).[30]

The citizens left homeless by Omar resided in a tent city nicknamed Camp Omar, consisting of 200 tents holding more than 1,000 people.[2][17] Volunteers and military efforts cleaned most of the debris on the island within a few weeks.[2] Many important roads were reopened by three days after the storm.[12] The power took four weeks to be restored island-wide, disrupting schools and businesses,[31] although water access was expected to be restored within a few days of the storm.[12] Schools reopened on September 14, and most businesses resumed their work by the end of the month.[17] The United States military ceased relief operations on September 19, though complete recovery was disrupted by the passage of several subsequent typhoons. These storms caused less damage than normal after Omar wrecked the more vulnerable structures. As a result, it became difficult to discern the damage between Omar and Typhoon Gay in December 1992.[5] A 1993 study in the medical journal Anxiety found that 7.2% of 320 participants affected by Omar developed acute stress reaction, and another 15% developed early traumatic stress response, especially those affected by the later typhoons. About 5.9% of the participants displayed symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, similar to the levels shown after Hurricane Hugo in 1989.[31]

Due to the destruction in Guam, the name Omar was retired and was replaced with Oscar in 1993.[2][32]

See also

- Typhoon Rita (1978)

- Typhoon Andy (1982)

- Typhoon Herb (1996)

- Typhoon Mawar (2023)

Notes

- Wind estimates averaged over one minute are derived from the American-based Joint Typhoon Warning Center in Hagåtña, Guam.[2] Winds averaged over ten minutes are derived from the Japan Meteorological Agency, which is the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the western Pacific Ocean.[3]

- All damage totals are in 1992 values of their respective currencies.

- PAGASA stands for the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration

- The total was originally reported in Philippine pesos. Total converted via the footnoted site.[21]

- The total was originally reported in Japanese yen. Total converted via the Oanda Corporation website.[24]

References

- Top 25 Natural Disasters in Philippines According to Number of Killed (1901–2000) (PDF) (Dataset). Kobe, Japan: Asian Disaster Reduction Center. 2003. p. 12. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- Mautner, Donald A.; Guard, Charles P. (1992). 1992 Annual Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). Annual Tropical Cyclone Reports. Hagåtña, Guam: Joint Typhoon Warning Center. pp. 80–89. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- "Latest Advisories on Current Tropical Cyclones Hurricanes Typhoons". Tropical Cyclone Programme. Geneva, Switzerland: World Meteorological Organization. n.d. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- "RSMC Best Track Data (1990–1999)" (TXT) (Database). Tokyo, Japan: Japan Meteorological Agency. June 2, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- Angel, William; Hammer, Greg; Hollifield, Jay; Weaver, Sharon (September 1992). "Typhoon Omar strikes Guam on August 28, 1992" (PDF). Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena. 34 (9): 31–33. ISSN 0039-1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2015.

- "Section 2: Tropical Cyclone Overview for 1992" (PDF). Tropical Cyclones in 1992. Kowloon, Hong Kong: Hong Kong Observatory. September 1994. pp. 14–15. 551.515.2:551.506.1(512.317). Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- 1992 年歐馬(OMAR)颱風 (PDF). Typhoon Data Bank (Report) (in Chinese). Taipei, Taiwan: Central Weather Bureau. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 11, 2015. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- "Tropical storm heads for Guam". The Free-Lance Star. Vol. 108, no. 202. Fredericksburg, Virginia. Associated Press. August 26, 1992. p. A2. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- "Tropical storm moves closer to Guam". Associated Press News. Hagåtña, Guam. August 26, 1992. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- "After the storm: Thousands on Guam lose homes in typhoon". New York Times. New York, New York. August 30, 1992. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- "Guam typhoon mop up begins". The Prescott Courier. Vol. 110, no. 200. Prescott, Arizona. Associated Press. August 31, 1992. p. 2A. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- "Federal assistance to typhoon-stricken Guam". New York, New York. PR Newswire. August 28, 1992.

- Roth, David M. (April 30, 2015). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. College Park, Maryland: Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

- "Guam hit hard by Typhoon Omar". TimesDaily. Vol. 123, no. 242. Florence, Alabama. Associated Press. August 29, 1992. p. 7A. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- Disaster Assistance: DOD's Support for Hurricanes Andrew and Iniki and Typhoon Omar. Report to the Chairman, Subcommittee on Readiness, Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: United States General Accounting Office. June 23, 1993. GAO/NSIAD-93-180. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- "A month after Typhoon Omar, residents of Guam rebuilding". Star-News. Vol. 125, no. 302. Wilmington, North Carolina. Associated Press. September 20, 1992. p. 8A. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- "Typhoon Omar pummels Guam". The Telegraph. Vol. 122, no. 446. London, UK. Associated Press. August 28, 1992. p. 20. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- "Typhoon Omar roars closer to the Philippines". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. September 3, 1992. p. 23. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- "Destructive Typhoons 1970-2003" (Dataset). Quezon City, Philippines: National Disaster Coordinating Council. November 9, 2004. entries 121–140. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- "Historical exchange rates". x-rates.com. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- 本颱風摘要. Typhoon Data Bank (Report) (in Chinese). Taipei, Taiwan: Central Weather Bureau. August 5, 2011. Archived from the original on April 11, 2015. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- Typhoon 199215 (Omar). Digital Typhoon (Report). Tokyo, Japan: National Institute of Informatics. n.d. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- "Historical Exchange Rates" (Database). Toronto, Canada: Oanda Corporation. n.d. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- Weather Disaster Report (1992-918-05). Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). Tokyo, Japan: National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- "Typhoon Omar devastates Guam". The Spokesman-Review. Vol. 6, no. 95 (State ed.). Spokane, Washington. August 29, 1992. p. A3. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- "Bush declares Guam federal disaster area". Washington, D.C. United Press International. August 28, 1992.

- Guard, Charles; Hamnett, Michael; Newmann, Charles; Lander, Mark; Siegrist, H. Galt Jr. (1999). Typhoon Vulnerability Study for Guam (PDF) (Report). Mangilao, Guam: Water and Environmental Research Institute of the Western Pacific. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 24, 2012. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- "Dire Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act, 1992, Including Disaster Assistance To Meet the Present Emergencies Arising From the Consequences of Hurricane Andrew, Typhoon Omar, Hurricane Iniki, and Other Natural Disasters, and Additional Assistance to Distressed Communities". Title II: Department of Defense – Military, Bill No. H.R.5620 of 1992. Washington, D.C.: 102nd Congress of the United States of America (1991–1992). Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- Gutierrez, Carl (January 11, 1996). Executive Order No. 96-01 (PDF) (Report). Officer of the Governor of the Territory of Guam. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 22, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- Staab, Jeffrey P.; Grieger, Thomas A.; Fullerton, Carol S.; Ursano, Robert J. (1996). "Acute stress disorder, subsequent posttraumatic stress disorder and depression after a series of typhoons". Anxiety. 2 (5): 219–225. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1522-7154(1996)2:5<219::AID-ANXI3>3.0.CO;2-H. PMID 9160626.

- Lei, Xiaotu; Zhou, Xiao (February 2012). "Summary of retired typhoons within the western North Pacific Ocean". Tropical Cyclone Research and Review. 1 (1): 23–32. doi:10.6057/2012TCRR01.03.