Tropic Shale

The Tropic Shale is a Mesozoic geologic formation. Dinosaur remains are among the fossils that have been recovered from the formation,[2] including Nothronychus graffami. The Tropic Shale is a stratigraphic unit of the Kaiparowits Plateau of south central Utah. The Tropic Shale was first named in 1931 after the town of Tropic where the Type section is located.[3] The Tropic Shale outcrops in Kane and Garfield counties, with large sections of exposure found in the Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument.

| Tropic Shale | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: Cenomanian to Turonian | |

Tropic Shale at its type location at Tropic, Utah | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Kaiparowits Plateau |

| Underlies | Straight Cliffs Formation |

| Overlies | Dakota Formation |

| Thickness | Maximum 1,450 feet (440 m), average 600 feet (180 m) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Shale |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 37.629°N 112.076°W |

| Region | |

| Country | |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Exposures near Tropic, Garfield County, Utah |

| Named by | Gregory and Moore, 1931[1] |

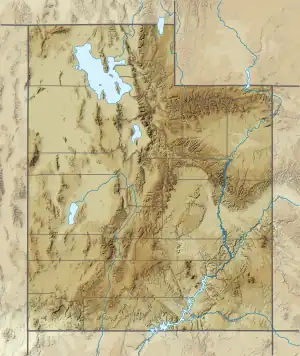

Tropic Shale (the United States)  Tropic Shale (Utah) | |

Geology

The Tropic Shale is predominantly marine mudstone and claystone, with several radioisotopically-dated bentonite marker beds, and occasional sandstone layers deposited during the late Cretaceous Period during the Upper Cenomanian through the Middle Turonian (95-92 Ma). The Tropic Shale has an average thickness range from 183–274 m.

The Tropic Shale conformity overlies the Dakota Formation and underlies the Straight Cliffs Formation. The top of the Dakota Formation is known for its sandier coarsening up sequences and estuarine shell beds. The distinction between the Tropic Shale and underlying Dakota is marked by the appearance of marine mudstones. In some localities there is a sharp non conformable contact between the Dakota Formation and Tropic Shale. The contact with the overlying Straight Cliffs is gradational with the distinction between the two units defined as the point where sandstone becomes more abundant than shale.

The Tropic Shale has two dominate lithologies, with the lower two thirds of the formation consisting of a bluish gray calcareous mudstone that encompasses eleven ammonoid biozones, and the upper third that is a darker gray and non-calcareous that encompasses only one or two ammonoid biozones. Additionally the upper portion, hummocky cross stratified and turbiditic sandstone beds become more common.

Stratigraphy and age

The Tropic Shale has been correlated temporally with the Tununk Member of the Mancos Shale in central Utah, the Allen Valley Shale of the western Wasatch Range in Utah,[4] the Mancos Shale exposed at Black Mesa, Arizona, and additionally the Bridge Creek Member of the Greenhorn Limestone at Pueblo, Colorado. Bentonite layers present in all these formations have been correlated throughout deposits associated with the Western Interior Seaway.

Solid and septarian carbonate concretionary nodule horizons are characteristic of the lower and middle parts of the formation informally named as concretionary layer 1-4. The statigraphically lowest is layer one with the stratigraphically highest being layer 4. Layers 1 and 2 seem to be in isolated sections while layers 3 and 4 seem to have a wide distribution and act as marker beds between Bentonite "A" and "B". The ammonites Sciponoceras gracile and Euomphaloceras septemseriatum are commonly preserved in these concretionary nodules.

The bentonites of the Tropic Shale form erosional benches that can be easily traced throughout the formation. These bentonites have been correlated with other formations that are interpreted as part of the Western Interior Seaway. They are white to light grey when freshly exposed or can have a yellowish discoloration when weathered. The average thickness of these bentonite beds is 1–6 mm. They are organized using a lettered system (A-E) with the lowest stratigraphically positioned bentonite being "A" and the highest stratigraphically positioned bentonite being "E". Several of these bentonites have also been related to known ammonoid biozones. Bentonites "A" and "B" are associated with massive accumulations of clam fossils.

Radioisotopically dated beds:[5]

| Bentonite | Date | Error +/- | Correlated Ammonoid Zone |

|---|---|---|---|

| "A" | 93.49 | 0.89 | Upper Cenomanian biozone Euomphaloceras septemseriatum |

| "B" | 93.59 | 0.58 | upper Cenomanian biozone of Neocardioceras juddii |

| "C" | 93.25 | 0.55 | Lower Turonia biozone of Vascoceras birchbyi |

| "D" | 93.40 | 0.63 | - |

| "E" | - | - | - |

| Genus | Species | Date | Error +/- | Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prionocyclus | hyatti | 92.46 | 0.58 | Middle Turonian |

| Collignoniceras | praecox | - | - | Middle Turonian |

| Collignoniceras | woollgari | - | - | Middle Turonian |

| Mammites | nodosoides | - | - | Lower Turonian |

| Vascoceras | birchbyi | 93.48 | 0.58 | Lower Turonian |

| Pseudoaspidoceras | flexuosum | 93.1 | 0.42 | Lower Turonian |

| Watinoceras | devonense | - | - | Lower Turonian |

| Nigericeras | scotti | - | - | Upper Cenomanian |

| Neocardioceras | juddii | 93.32 / 93.82 | .38 / .3 | Upper Cenomanian |

| Burroceras | clydense | - | - | Upper Cenomanian |

| Euomphaloceras | septemseriatum | 93.68 | 0.5 | Upper Cenomanian |

| Vascoceras | diartianum | 93.99 | 0.72 | Upper Cenomanian |

Paleontology

Fossils have been found throughout the entire section of the Tropic Shale. Invertebrates such as ammonites and innoceramid clams seem to dominate. Shark remains consist almost entirely of tooth remains while marine reptiles vary in preservation from isolated fragments to articulated specimens.

The Tropic Shale is known for a wide assortment of marine vertebrates with minor contributions from terrestrial vertebrates. Recovered fossils include sharks, fishes, marine reptiles, turtles and dinosaurs. The marine deposition of vertebrates such as dinosaurs is interpreted as animals being washed out to sea while still alive in a storm event that then drowned or decomposing animals that were washed out to sea in a bloat and float model of transportation.[7]

Dinosaurs

| Dinosaurs reported from the Tropic Shale | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Presence | Material | Notes | Images |

| Nothronychus | N. graffami | Kaiparowits Basin, Kane County, Utah.[8] | UMNH VP 16420 (nearly complete postcranial skeleton).[7][8] | A therizinosaur. |  |

Mosasaurs

| Mosasaurs reported from the Tropic Shale | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Presence | Material | Notes | Images |

| Sarabosaurus | S. dahli | GLCA site 327, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area.[9] | Fragments of cranium, mandible, and vertebrae (UMNH VP21800). | A plioplatecarpine. | |

Plesiosaurs

| Plesiosaurs reported from the Tropic Shale | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Presence | Material | Notes | Images |

| Brachauchenius | B. lucasi | Partial skeleton (MNA V9433).[7] | A pliosaurid. |  | |

| Dolichorhynchops | D. tropicensis | Nearly complete specimen with associated gastroliths (MNA V10046).[7] | A polycotylid. | ||

| Eopolycotylus | E. rankini | Partial skeleton (MNA V9445).[7] | A polycotylid. |  | |

| Palmulasaurus | P. quadratus | Partial skeleton (MNA V9442).[7] | A polycotylid. |  | |

| Trinacromerum | T. ?bentonianum | Multiple specimens.[7] | A polycotylid. | ||

Turtles

| Turtles reported from the Tropic Shale | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Presence | Material | Notes | Images |

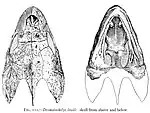

| Desmatochelys | D. lowi | Partial skeleton (MNA V9446).[7] | A protostegid. |  | |

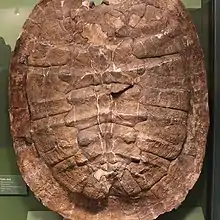

| Naomichelys | N. sp. | Fragmentary carapace & plastron with a limb fragment (MNA V9461).[7] | A helochelydrid. |  | |

| Protostegidae Genus et sp. indet. | Indeterminate | MNA V9458.[7] | Provisionally identified as a possible new genus.[7] | ||

Bony fish

| Bony fish reported from the Tropic Shale | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Presence | Material | Notes | Images |

| Gillicus | G. arcuatus | Nearly complete articulated skeleton (MNA V10081).[7] | An ichthyodectiform. | ||

| Ichthyodectes | I. ctenodon | A specimen with dentaries, 6 vertebrae & skull fragments (MNA V9467).[7] | An ichthyodectid. |  | |

| I. sp., cf. I. ctenodon | Fragmentary lower jaw (MNA V9483).[7] | An ichthyodectid. | |||

| Pachyrhizodus | P. leptopsis | Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument[10] | A disarticulated specimen (MNA V10651).[10] | A crossognathiform. |  |

| Pycnodontoidei | Genus & species undetermined | Premaxillae with dentition (MNA V10076).[7] | A pycnodont. | ||

| Xiphactinus | X. sp., cf. X. audax | Fin, vertebral & skull elements.[7] | An ichthyodectid. |  | |

Cartilaginous fish

| Cartilaginous fish reported from the Tropic Shale | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Presence | Material | Notes | Images |

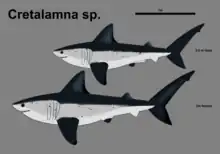

| Cretalamna | C. appendiculata | Teeth.[7] | A megatooth shark. |  | |

| Cretoxyrhina | C. mantelli | 7 teeth.[7] | A mackerel shark. |  | |

| Ptychodus | P. anonymus | 16 teeth.[7] | A ptychodontid. |  | |

| P. decurrens | Vertebrae & hundreds of teeth.[7] | A ptychodontid. |  | ||

| P. occidentalis | 4 teeth.[7] | A ptychodontid. | |||

| P. sp. cf. P. mammillaris | Numerous teeth.[7] | A ptychodontid. |  | ||

| P. sp. indet. | A tooth (MNA V9982).[7] | A ptychodontid. | |||

| P. whipplei | Multiple teeth.[7] | A ptychodontid. | |||

| Ptychotrygon | cf. P. sp. | Partial tooth (MNA V10097).[7] | A sawskate. |  | |

| Scapanorhynchus | S. raphiodon | Teeth.[7] | A mitsukurinid. |  | |

| Squalicorax | S. curvatus | Multiple teeth.[7] | An anacoracid. | ||

Invertebrates

The Tropic Shale is known for its large invertebrate assemblage. Ammonites seem to be major contributors to the ecosystem with oysters and gastropods rounding out the ecosystem. Cold hydrocarbon seeps seem to have their own invertebrate biozone located at the bottom of the formation. Rudists and solitary corals seem to be quite rare and have not been studied due to their lack of presence in the Tropic Shale as they are recorded from other formations associated with the Western Interior Seaway.[11]

| Genus | Species | Common Name |

|---|---|---|

| Callianassa | ?sp. | Mud Shrimp |

| Turritella | ?sp | Gastropod |

| Goniocylichna | ?sp | Gastropod |

| Paleopsephaea | ?sp | Gastropod |

| Toruatellaea | ?sp | Gastropod |

| Preissoptera | prolabiata | Gastropod |

| Mytiloides | hattini | Bivalve |

| Nymphalucina | cf. linearia | Bivalve |

| Solemyid | ?sp | Bivalve |

| Arcoid | ?sp | Bivalve |

| Inoceramus | pictus | Bivalve |

| Rudistid | Bivalve | |

| Pycnodonte | newberryi | Oyster |

| Prionocyclus | hyatti | Ammonite |

| Collignonicras | praecox | Ammonite |

| Collignonicras | woollgari | Ammonite |

| Mammites | nodosoides | Ammonite |

| Vascoceras | birchbyi | Ammonite |

| Pseudaspidoceras | flexuosum | Ammonite |

| Watinoceras | devonense | Ammonite |

| Nigericeras | scotti | Ammonite |

| Neocardioceras | juddii | Ammonite |

| Burroceras | clydense | Ammonite |

| Euomphaloceras | septemseriatum | Ammonite |

| Vascoceras | diartianum | Ammonite |

| Sciponoceras | gracile | Ammonite |

Paleobotany

Limited occurrences of petrified wood have been reported in the Tropic Shale. These are interpreted predominately as drift wood that settled to the bottom of the inland seaway.[12]

Paleoecology

During the late Cretaceous the Western Interior Seaway was occupied by a sea that is regressing by the Turonian. There was a brief transgression as the estuary like Dakota Formation was replaced by deeper marine shelf deposits. This transgression/regression (named the Greenhorn) cycle lasted about four million years and correlates to an oceanic anoxic event. Evidence of the change is characterized by massive deposits of calcium carbonate in the marine mudstones that can be seen in the upper third of the Tropic Shale when calcium carbonate is absent.

During the late Cretaceous widespread conditions of oceanic anoxia occurred across the Cenomanian–Turonian (C-T) stage boundary between about 94.2 and 93.5 million years ago (Oceanic Anoxic Event II, OAE II).[12] This Cenomanian–Turonian Boundary Event is reflected by one of the most extreme carbon cycle perturbations in Earth's history. Studies have been done on the marine reptiles to determine the impact of OAE II on the biodiversity of the group in the Western Interior Seaway. Results from that study seem to suggest that at least locally the OAE II had little to no effect on marine reptile diversity.[13]

Cold hydrocarbon seep bioherms in the lower portion of the Tropic Shale during the Cenomanian give glimpses of different ecosystems to the marine shelf deposits. These bioherms tend to be around one meter tall and up to three meters wide with large concentrations of invertebrates surrounding the seeps.

References

- Geolex — Unit Summary, USGS

- Weishampel, et al. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution." Pp. 517-607.

- Gregory, H.E. and Moore, R.C., 1931, The Kaiparowits region, a geographic and geologic reconnaissance of parts of Utah and Arizona: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper, 164, 161 p.

- Hintze, L.F., 1988. Geologic History of Utah. Frigham Young University Geology Studies, Special Publication 7.

- Obradovich, D., 1993. A Cretaceous time scale. W.G.E. Caldwell, E.G. Kauffman (Eds.), Evolution of the Western Interior Basin, Geological Association of Canada (1993), Special Paper 39 pp. 379-396

- Cobban, W.A., Dyman, T.S., Pollock, G.L., Takahashi, K.I., Davis, L.E., & Riggin, D.B., 2000. Inventory of Dominantly Marine and Brackish-Water Fossils from Late Cretaceous Rocks in and near Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument, Utah. Geology of Utah's Parks and Monuments, Utah Geological Association, 28

- Albright, L.B., Gillette, D.D., Titus, A.L., 2013. Fossil vertebrates from the Tropic Shale (Upper Cretaceous), southern Utah. In: Titus, A.L., Loewen, M.A. (Eds.), At the Top of the Grand Staircaes, The Late Cretaceous of Southern Utah. Indiana University Press.

- Zanno, Lindsay E.; Gillette, David D.; Albright, L. Barry; Titus, Alan L. (2009-10-07). "A new North American therizinosaurid and the role of herbivory in 'predatory' dinosaur evolution". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1672): 3505–3511. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1029. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 2817200. PMID 19605396.

- Polcyn, Michael J.; Bardet, Nathalie; Albright, L. Barry; Titus, Alan (June 2023). "A new lower Turonian mosasaurid from the Western Interior Seaway and the antiquity of the unique basicranial circulation pattern in Plioplatecarpinae". Cretaceous Research. 151: 105621. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2023.105621.

- Schmeisser McKean, Rebecca L.; Shackelton, Allison L.; Gillette, David D. (2018). "First Occurrence of Pachyrhizodus leptopsis in the Tropic Shale (Cenomanian-Turonian) of southern Utah". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. doi:10.1130/abs/2018RM-313905.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Titus, A.L., Roberts, E.M., & Albright, L.B., 2013. Geologic overview. In: Titus, A.L., Loewen, M.A. (Eds.), At the Top of the Grand Staircase, The Late Cretaceous of Southern Utah. Indiana University Press.

- Dean, W.E., Kauffman, E.G. & Arthur, M.A. 2013. Accumulation of Organic Carbon-Rich Strata along the Western Margin and in the Center of the North American Western Interior Seaway during the Cenomanian-Turonian Transgression. At the top of the Grand Staircase (42-56)

- Schmeisser McKean, R.L. & Gillette, D.D. 2015. Taphonomy of large marine vertebrates in the Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian-Turonian) Tropic Shale of southern Utah. Cretaceous Research, 56(278-292)

- Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pp. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.