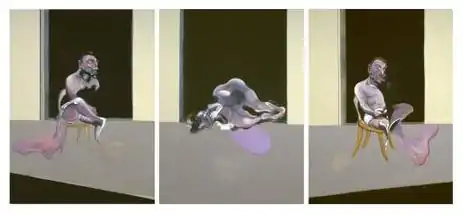

Triptych, May–June 1973

Triptych, May–June 1973 is a triptych completed in 1973 by the Irish-born artist Francis Bacon (1909–1992). The oil-on-canvas was painted in memory of Bacon's lover George Dyer, who committed suicide on the eve of the artist's retrospective at Paris's Grand Palais on 24 October 1971. The triptych is a portrait of the moments before Dyer's death from an overdose of pills in their hotel room.[1] Bacon was haunted and preoccupied by Dyer's loss for the remaining years of his life[2] and painted many works based on both the actual suicide and the events of its aftermath. He admitted to friends that he never fully recovered, describing the 1973 triptych as an exorcism of his feelings of loss and guilt.[3]

The work is stylistically more static and monumental than Bacon's earlier triptychs of Greek figures and friends' heads. It has been described as one of his "supreme achievements" and is generally viewed as his most intense and tragic canvas.[3] Of the three Black Triptychs Bacon painted when confronting Dyer's death, Triptych, May–June 1973 is generally regarded as the most accomplished.[4] In 2006, The Daily Telegraph's art critic Sarah Crompton wrote that "emotion seeps into each panel of this giant canvas ... the sheer power and control of Bacon's brushwork take the breath away".[5] Triptych, May–June 1973 was purchased at auction in 1989 by Esther Grether for $6.3 million, then a record for a Bacon painting.[6][7]

Biographical context

Francis Bacon met George Dyer in a Soho pub. According to Bacon "George was down the far end of the bar and he came over and said 'You all seem to be having a good time, can I buy you a drink?'" (Francis Bacon quoted in: Michael Peppiat, Francis Bacon: Anatomy of an Enigma, London 2008, p. 259). From that point on, Dyer became devoted to Bacon. He admired his intellect and power and was in awe of his self-confidence. He felt as if he had found a purpose, as the prominent artist's companion.[8] Dyer was then about thirty years old and had grown up in the East End of London in a family steeped in crime. He had spent his life drifting between theft, juvenile detention center and jail. Typical of Bacon's taste in men, Dyer was fit, masculine, and not an intellectual.

Bacon's relationships prior to Dyer had all been with older men who were as tumultuous in temperament as the artist himself, but each had been the dominating presence. Peter Lacy, his first lover, would often tear up the young artist's paintings, beat him up in drunken rages, and leave him on the street half-conscious.[9] Bacon was attracted to Dyer's vulnerability and trusting nature. Dyer was impressed by Bacon's self-confidence and his artistic success, and Bacon acted as a protector and father figure to the insecure younger man.[10] Dyer was, like Bacon, a borderline alcoholic and similarly took obsessive care with his appearance. Pale-faced and a chain-smoker, Dyer typically confronted his daily hangovers by drinking again. His compact and athletic build belied a docile and inwardly tortured personality; the art critic Michael Peppiatt described him as having the air of a man who could "land a decisive punch". Their behaviours eventually overwhelmed their affair, and by 1970, Bacon was merely providing Dyer with enough money to stay more or less permanently drunk.[10]

As Bacon's work moved from the extreme subject matter of his early paintings to portraits of friends in the mid-1960s, Dyer became a dominating presence in the artist's work.[11] Bacon's treatment of his lover in these canvasses emphasises his subject's physicality while remaining uncharacteristically tender. More than any other of the artist's close friends portrayed during this period, Dyer came to feel inseparable from his effigies. The paintings gave him stature, a raison d'être, and offered meaning to what Bacon described as Dyer's "brief interlude between life and death".[12] Many critics have cited Dyer's portraits as favourites, including Michel Leiris and Lawrence Gowling. Yet as Dyer's novelty diminished within Bacon's circle of sophisticated intellectuals, the younger man became increasingly bitter and ill at ease. Although Dyer welcomed the attention the paintings brought him, he did not pretend to understand or even like them. "All that money an' I fink they're reely 'orrible", he observed with choked pride.[13] He abandoned crime but soon descended into alcoholism. Bacon's money allowed Dyer to attract hangers-on who would accompany him on massive benders around London's Soho. Withdrawn and reserved when sober, Dyer was insuppressible when drunk, and would often attempt to "pull a Bacon" by buying large rounds and paying for expensive dinners for his wide circle. Dyer's erratic behaviour inevitably wore thin—with his cronies, with Bacon, and with Bacon's friends. Most of Bacon's art world associates regarded Dyer as a nuisance—an intrusion into the world of high culture to which their Bacon belonged.[14] Dyer reacted by becoming increasingly needy and dependent. By 1971, he was drinking alone and was only in occasional contact with his former lover.

In October 1971, Dyer accompanied Bacon to Paris for the opening of the artist's retrospective at the Grand Palais. The show was the high point of Bacon's career to date, and he was now being described as Britain's "greatest living painter". Dyer was now a desperate man, and although he was "allowed" to attend, he was well aware that he was "slipping", in every sense, out of the picture. To draw Bacon's attention he earlier planted cannabis in Bacon's flat, then phoned the police,[15] and he had attempted suicide on a number of occasions.[16] Dyer committed suicide, via an overdose of barbiturates, on the eve of the Paris exhibition in their shared hotel room. Bacon spent the following day surrounded by people eager to meet him. In mid-evening he was informed that Dyer had taken an overdose of barbiturates and was dead. Though devastated, Bacon continued with the retrospective and displayed powers of self-control "to which few of us could aspire", according to Russell.[2] Bacon was deeply affected by the loss of Dyer, and he had recently lost four other friends and his nanny. From this point on, death haunted his life and work.[17] Though he gave a stoic appearance at the time, he was inwardly broken. He did not express his feelings to critics, but later admitted to friends that "daemons, disaster and loss" now stalked him as if his own version of the Eumenides.[18] Bacon spent the remainder of his stay in Paris attending to promotional activities and funeral arrangements. He returned to London later that week to comfort Dyer's family. The funeral proved to be an emotional affair for all, and many of Dyer's friends, including hardened East-End criminals, broke down in tears. As the coffin was lowered into the grave one attendant screamed "you bloody fool!". Although Bacon remained stoic throughout, in the following months Dyer preoccupied his imagination as never before. To confront his loss, he painted a number of tributes on small canvasses and his three "Black Triptych" masterpieces.[19]

Description

In each panel, Dyer is framed by a doorway, and set against a flat, anonymous foreground coloured with black and brown hues. In the left frame, he is seated on a toilet with his head crouched between his knees as if in pain.[20] Although his arched back, thighs and legs are according to the Irish critic Colm Tóibín, "lovingly painted", Dyer is by now clearly a broken man. The central panel shows Dyer sitting on the toilet bowl in a more contemplative pose, his head and upper body writhing beneath a hanging lightbulb which throws a large bat-like shadow formed in the shape of a demon or Eumenide. The art critic Sally Yard has noted that in the portrayal of Dyer's flesh, "life seems to visibly drain ... into the substantial character of the shadow beneath him".[21] Dyer's posture suggests he is seated on a lavatory bowl, though the object is not described.[1] Schmied has proposed that in this frame the blackness of the background has enveloped the subject, and it "seems to be advancing forward over the threshold, threatening the viewer like a flood or a giant bat with flapping wings and extended claws."[20]

In the right panel, Dyer is shown with his eyes shut, vomiting into a hand basin. In the two outer frames his figure is shadowed by arrows, pictorial devices that Bacon often used to place a sense of energy into his paintings. In this work, the arrows point to a man about to die, and according to Tóibín they scream "Here!", "Him!".[1] The arrow of the right panel, according to Tóibín, points to a "dead figure on the lavatory bowl, as though telling the Furies where to find him".[1] The triptych is centralised by the lightbulb, and by the fact that Dyer faces inwards in the two outer canvasses. The triptych's composition and setting are poised to suggest instability, and the doors in each side panel are splayed outwards as if to look into the darkness of the foreground.[22]

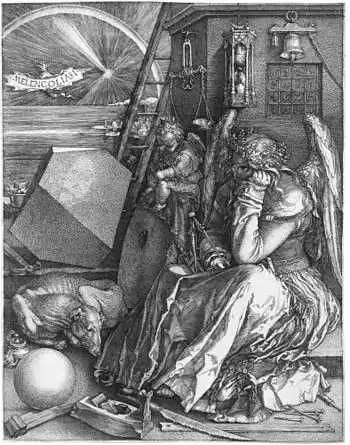

Triptych, May–June 1973 has been said to achieve its tension by locating voluptuously described figures in an austere, cage-like space. The foreground of each panel is bounded by a wall, which runs parallel to a framing door. Each door admits a stark black into its frame, while the walls establish a link between each of the three Black Triptychs.[23] In 1975, the curator Hugh M. Davis noted that while Bacon's earlier triptychs had been set in public spaces "open to all kinds of visitor", the Black Triptychs are set in a "deeply private realm, to which only the individual—accompanied, perhaps, by one or two of his closest friends—has access".[24] In 1999, Yard wrote that the sense of foreboding and ill-omen conjured by the Eumenides of Bacon's Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944) reappears in the triptych as a "batlike void that snared the figure of George Dyer as he subsides into the supple curves of death".[25] John Russell observed that the painting's background describes an area which is half studio, half condemned cell. A reviewer of the 1975 Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition found a resemblance between the concept of the central panel and Albrecht Dürer's engraving Melencolia I (1514)—in the figure's pose, the bat form, and the panel's radiance—suggesting that Bacon's late triptychs evoke "memorable figural formulations" of classic Western culture.[26]

Bacon later stated that "painting has nothing to do with colouring surfaces", and in general he was not preoccupied with detailing his backgrounds: "When I feel that I have to some extent formed the image, I put the background in to see how it's going to work and then I go with the image itself." He told David Sylvester that he intended his "hard, flat, bright ground" to juxtapose with the complexity of the central images, and noted that "for this work, it can work more starkly if the background is very united and clear. I think that probably is why I have used a very clear background against which the image can articulate itself". Bacon usually applied paint to the background quickly, and with "great energy"; however, he thought of it as a secondary element. He used its colour to establish tone, but in his mind the real work began when he came to paint the figures.

Critics have argued whether the triptych should be read sequentially from left to right.[27] Davies believes the work is a narrative, panoramic view of Dyer's suicide, and that the triptych's format implies a temporal continuity between each frame. Ernst van Alphen has argued that, notwithstanding spatial inconsistencies—the light bulb featured in the central panel is missing from the two outer canvasses, while the doorway view is reversed in the center panel—the triptych is a "plain representation of a story".[28]

The Black Triptychs

Bacon's work from the 1970s has been described by the art critic Hugh Davies as the "frenzied momentum of a struggle against death". Bacon admitted during a 1974 interview that he thought the most difficult aspect of aging was "losing your friends". This was a bleak period in his life, and though he was to live for another seventeen years, he felt that his life was almost over, "and all the people I've loved are dead". His concern is reflected in the darkened flesh and background tones of his paintings from this period.[29] His acute sense of mortality and awareness of the fragility of life were heightened by Dyer's death in Paris. In the next three years he painted many images of his former lover, including the series of three "Black Triptychs" which have come to be seen as among his best work. A number of characteristics bind the triptychs together: the form of a monochromatically rendered doorway features centrally in all, and each is framed by flat and shallow walls.[29] In each three Dyer is stalked by a broad shadow; which takes the form of pools of blood or flesh in the outer panels and the wings of the angel of death in the left hand and central images.[30] In its display caption for Triptych–August 1972 the Tate gallery wrote, "What death has not already consumed seeps incontinently out of the figures as their shadows."[31]

Each of the three Black Triptychs displays sequential views of a single figure, and each seems to be intended to be viewed as if stills from a film.[22] The figures rendered are not drawn from any of Bacon's usual intellectual sources; they do not depict Golgotha, Handes, or Leopold Bloom. In these pictures Bacon strips Dyer from the context of both Dyer's own life and the artist's life, and presents him as a nameless, slumped, gathering of flesh, awaiting the onset of death.[32] Describing the Black Triptychs in 1993, the art critic Juan Vicente Aliaga wrote that "the horror, the abjection that oozed from the crucifixes has been transformed in his last paintings into quiet solitude. The masculine bodies entwined in a carnal embrace have given way to the solitary figure leaning over the washbasin, standing firm on the smooth ground, neutral, bald-headed, his convex back deformed, his testicles contracted in a fold."[33]

When asked by the broadcaster Melvyn Bragg in 1984 if the portraits painted in the wake of Dyer's death were depictions of his emotional reaction to the event, Bacon replied that he did not consider himself to be an "expressionist painter". He explained that he was "not trying to express anything, I wasn't trying to express the sorrow about somebody committing suicide ... but perhaps it comes through without knowing it".[34] When Bragg inquired if he often thought about death, the artist replied that he was always aware of it, and that although "it's just around the corner for [me], I don't think about it, because there's nothing to think about. When it comes, it's there. You've had it." Reflecting on the loss of Dyer, Bacon observed that as part of aging, "life becomes more of a desert around you". He told Bragg that he believed in "nothing. We are born and we die and that's it. There is nothing else." Bragg asked Bacon what he did about that reality, and after the artist told him he did nothing about it, Bragg pleaded, "No Francis, you try and paint it."[34]

Throughout his career, Bacon consciously and carefully avoided explaining the meaning behind his paintings, and pointedly observed that they were not intended as narratives, nor open to interpretation. When Bragg challenged him with the observation that Triptych, May–June 1973 was the nearest the artist had come to telling a story, Bacon admitted that "it is in fact the nearest I've ever done to a story, because you know that is the triptych of how [Dyer] was found". He went on to say that the work reflected not just his reaction to Dyer's death, but his general feelings about the fact that his friends were then dying around him "like flies".[35] A borderline alcoholic himself, Bacon continued to explain that his dead friends were "generally heavy drinkers", and that their deaths led directly to his composition of a series of meditative self-portraits which emphasised his own aging and awareness of the passage of time.[34]

See also

Notes

- Tóibín, Colm. "Such a Grip and Twist". The Dublin Review, 2000.

- Russell 1971, p. 151

- Dawson (2000), p. 108.

- Davis, Yard (1986), p. 65.

- Crompton, Sarah. "Long live mortality". The Daily Telegraph, 11 July 2006. Retrieved on 4 July 2007.

- Thornton, Sarah. "Francis Bacon claims his place at the top of the market]". The Art Newspaper, 29 August 2008

- "Post-War Works Shine at Christie's" Artnet News, 16 November 2000. Retrieved on 7 May 2007.

- Sotheby's

- Heaney, Joe. "Love is the Devil". Gay Times, September 2006.

- Peppiatt (1996), p. 211.

- Harrison, Martin. "Francis Bacon: lost and found". Apollo Magazine, 1 March 2005.

- Peppiatt (1996), p. 213.

- Peppiatt (1996), p. 214.

- Peppiatt (1996), p. 215.

- Norton, James. "The six loves of Francis Bacon". Sunday Herald, 13 March 2005.

- "George Dyer". Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, 2001

- Russell (1971), p. 178.

- Russell (1970), p. 179.

- Peppiatt (1996), p. 243.

- Schmied (1996), p. 82.

- Davis, Yard (1986), p. 69.

- Davies; Yard (1986), p. 74.

- Schmied (1996), p. 81.

- Davis, Hugh M. (1975). "Francis Bacon". Exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- Farr, Peppiatt, Yard (1999), p. 16.

- Canedy, Norman W. "Francis Bacon at the Metropolitan Museum (Current and Forthcoming Exhibitions)". The Burlington Magazine, 1975. Volume 117, issue 867. pp. 425–426.

- Wullschlager, Jackie. "Humanity in all its agony and emptiness". The Financial Times, 29 June 2006.

- van Alphen (1992), pp. 25–26.

- Davies; Yard (1986), p. 65.

- Davies; Yard (1986), pp. 67–76.

- "Triptych – August 1972". tate.org.uk. Retrieved on 13 June 2007.

- Schmied (1996), p. 84.

- Aliaga, Juan Vicente. "Francis Bacon — "Galerie Marlborough, Madrid, Spain". ArtForum, February 1993

- Bragg, Melvyn. "Francis Bacon". South Bank Show. BBC documentary film, first aired 9 June 1985.

- Sylvester (1987), p. 129. "People have been dying around me like flies and I've had nobody else to paint but myself ... I loathe my own face, and I've done self-portraits because I've had nothing else to do".

Sources

- van Alphen, Ernst (1992). Francis Bacon and the Loss of Self. (London) Reaktion Books. ISBN 0-948462-33-7

- Davies, Hugh; Yard, Sally, (1986). Francis Bacon. (New York) Cross River Press. ISBN 0-89659-447-5

- Dawson, Barbara; Sylvester, David,(2000). Francis Bacon in Dublin. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28254-4

- Farr, Dennis; Peppiatt, Michael; Yard, Sally (1999). Francis Bacon: A Retrospective. Harry N Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-2925-2

- Muir, Robin (2002). A Maverick Eye. (London) Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-54244-6.

- Peppiatt, Michael (1996). Anatomy of an Enigma. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3520-5

- Russell, John (1971). Francis Bacon (World of Art). Norton. ISBN 0-500-20169-2

- Schmied, Wieland (1996). Francis Bacon: Commitment and Conflict. (Munich) Prestel. ISBN 3-7913-1664-8

- Sylvester, David (1987). The Brutality of Fact: Interviews With Francis Bacon. (London) Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27475-4