Treaty of Fontainebleau (1631)

The Treaty of Fontainebleau (German: Vertrag von Fontainebleau) was signed on 30 May 1631 during the Thirty Years' War, at the Palace of Fontainebleau. It was a pact of mutual assistance between Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria, and France, for a period of eight years.

| |

| Signed | 30 May 1631 |

|---|---|

| Location | Palace of Fontainebleau, France |

| Expiration | 30 May 1639 |

| Original signatories |

|

| Parties | |

| Languages | German, French |

The treaty provides an example of the complex relationships between the various participants. In it, France agreed to protect Maximilian from Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, also a French ally and opponent of Emperor Ferdinand, Maximilian's overlord.

Attempts to keep it secret proved impossible, but Gustavus' death at Lützen in September 1632 ended Swedish ambitions in Bavaria.

Background

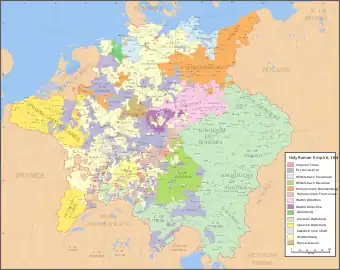

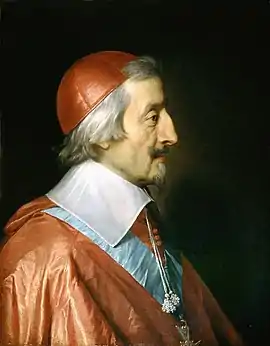

From around 1520 to 1750, European politics was dominated by the rivalry between France and the Habsburgs, rulers of Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. During the 1620s, France was divided by renewed religious wars and Cardinal Richelieu, chief minister from 1624 to 1642, avoided open conflict with the Habsburgs. Instead, he financed their opponents, including the Dutch, the Ottomans, and Danish intervention in the Thirty Years' War.[1]

Richelieu also tried to create an alternative power centre by backing the Wittelsbachs, rulers of Bavaria, Cologne, Jülich and Berg. Although held by a Habsburg since 1470, the Holy Roman Emperor was chosen by seven Prince-electors; Mainz, Cologne, Trier, Saxony, Brandenburg, Bohemia and the Palatinate. This provided France another way to influence Imperial politics.[2]

The Thirty Years War began in 1618 when the Protestant Frederick, ruler of the Palatinate, accepted the crown of Bohemia. Many German Protestants remained neutral, viewing it as an inheritance dispute and with Bavarian support, Emperor Ferdinand quickly suppressed the Bohemian Revolt. He then invaded the Palatinate and by 1622, Frederick was in exile, leaving Maximilian in possession. In 1623, the electoral vote previously held by the Palatinate was transferred to Bavaria, giving the Wittelsbachs control of two votes.[3]

However, depriving Frederick of his inheritance changed the nature and extent of the war, drawing in foreign powers. In 1625, the Protestant Christian IV of Denmark invaded Northern Germany but after some success, was defeated by the Imperial general Wallenstein and forced to withdraw in 1629. Ferdinand now enacted the Edict of Restitution; this required any property that had changed hands since 1552 restored to its original owner, which in nearly every case meant the Catholic Church. By effectively undoing the 1555 Peace of Augsburg, it forced moderate Protestants like John George of Saxony and George William of Brandenburg into opposition.[4]

This reignited the Protestant cause and in 1630, Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden landed in the Duchy of Pomerania, expelling Wallenstein. Richelieu used this to create an anti-Habsburg alliance, including Sweden, Saxony, Brandenburg and other German Protestants. Adding Catholic Bavaria balanced the alliance's appeal to other members of the Empire, and countered domestic accusations Richelieu favoured Protestants.[5]

Negotiations

In the January 1631 Franco-Swedish Treaty of Bärwalde, Richelieu agreed to fund Swedish military intervention for five years. In return, Gustavus promised to respect the neutrality of Bavaria and the lands of the Catholic League, but only so long as they did the same. The terms were so poorly drafted that as Richelieu himself pointed out, the presence of Bavarian officers in the Imperial army technically violated Maximilian's neutrality.[6]

Richelieu relied on his ability to restrain the Swedish king, but Maximilian was less confident; Gustavus had quickly established his superiority over the Imperial armies, and insisted Frederick be restored. One alternative was a proposal from Philip IV of Spain; sixty years of continuous warfare in the Spanish Netherlands and elsewhere had severely stretched the Spanish Empire. To exclude France and Sweden from Germany, he suggested a 'Habsburg alliance', consisting of Spain, Austria, the Spanish Netherlands, and as many German states as possible, Catholic or Protestant.[7]

Gaining Protestant support meant rescinding the Edict, which Ferdinand showed no desire to do, while Philip wanted the alliance to provide Spain with military support against France and the Dutch in the Low Countries. Both conditions were problematic, and Maximilian viewed a French alliance as an insurance policy against Sweden.[8]

Terms

Clauses One and Two set the period of the agreement as eight years, with each party providing the other military assistance, if their 'inherited or acquired' territories were attacked, which essentially confirmed Bavarian possession of the Palatinate. French assistance was set at 9,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry, or the financial equivalent, for Bavaria, 3,000 and 1,000 respectively. In Clauses Three and Four, they further undertook not to support attacks on either by another party.[9]

Clause Five confirmed French support for Bavaria's acquisition of the Palatinate's electoral vote, agreed by the Imperial Diet in 1623. Clause Six required the treaty and its terms to be kept secret, and Clause Seven qualified Maximilian's obligations as being subject to 'his oath to the Emperor and the Empire.'[10]

Aftermath

On 20 May, ten days before the treaty was signed, forces of the Catholic League, sacked the Protestant town of Magdeburg; over 20,000 were alleged to have died in the most serious atrocity of the entire war.[11]

At an Imperial conference held in August, Catholic hardliners succeeded in blocking concessions on the Edict; the combination meant Saxony allied with Gustavus and their combined army won an overwhelming victory over the League at Breitenfeld in September. This dramatically changed the balance of power and by early 1632, Swedish forces occupied much of Southwest Germany and Bavaria, including Munich. Gustavus' death at Lützen in September 1632 allowed Maximilian to regain his lost territories.[12]

References

- Wedgwood 1938, pp. 385–386.

- Bireley 2003, pp. 108–109.

- Spielvogel 2006, p. 447.

- Bireley 2003, p. 111.

- Bireley 2003, p. 110.

- O'Connell 1968, pp. 255–256.

- Bireley 2003, p. 122.

- O'Connell 1968, p. 252.

- Wilson 2010, p. 142.

- Wilson 2010, p. 143.

- O'Connell 1968, p. 255.

- Bireley 2003, p. 139.

Sources

- Bireley, Robert (2003). The Jesuits and the Thirty Years War: Kings, Courts, and Confessors. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521820172.

- O'Connell, Daniel Patrick (1968). Richelieu. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Spielvogel, Jackson J (2006). Western Civilization: Volume II: Since 1500. Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 9780534646042.

- Wedgwood, CV (1938). The Thirty Years War (2005 ed.). New York Review of Books. ISBN 978-1590171462.

- Wilson, Peter (2010). The Thirty Years War: A Sourcebook. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230242050.