Transmission medium

A transmission medium is a system or substance that can mediate the propagation of signals for the purposes of telecommunication. Signals are typically imposed on a wave of some kind suitable for the chosen medium. For example, data can modulate sound, and a transmission medium for sounds may be air, but solids and liquids may also act as the transmission medium. Vacuum or air constitutes a good transmission medium for electromagnetic waves such as light and radio waves. While a material substance is not required for electromagnetic waves to propagate, such waves are usually affected by the transmission media they pass through, for instance, by absorption or reflection or refraction at the interfaces between media. Technical devices can therefore be employed to transmit or guide waves. Thus, an optical fiber or a copper cable is used as transmission media.

Electromagnetic radiation can be transmitted through an optical medium, such as optical fiber, or through twisted pair wires, coaxial cable, or dielectric-slab waveguides. It may also pass through any physical material that is transparent to the specific wavelength, such as water, air, glass, or concrete. Sound is, by definition, the vibration of matter, so it requires a physical medium for transmission, as do other kinds of mechanical waves and heat energy. Historically, science incorporated various aether theories to explain the transmission medium. However, it is now known that electromagnetic waves do not require a physical transmission medium, and so can travel through the vacuum of free space. Regions of the insulative vacuum can become conductive for electrical conduction through the presence of free electrons, holes, or ions.

Optical medium

Telecommunications

A physical medium in data communications is the transmission path over which a signal propagates. Many different types of transmission media are used as communications channel.

In many cases, communication is in the form of electromagnetic waves. With guided transmission media, the waves are guided along a physical path; examples of guided media include phone lines, twisted pair cables, coaxial cables, and optical fibers. Unguided transmission media are methods that allow the transmission of data without the use of physical means to define the path it takes. Examples of this include microwave, radio or infrared. Unguided media provide a means for transmitting electromagnetic waves but do not guide them; examples are propagation through air, vacuum and seawater.

The term direct link is used to refer to the transmission path between two devices in which signals propagate directly from transmitters to receivers with no intermediate devices, other than amplifiers or repeaters used to increase signal strength. This term can apply to both guided and unguided media.

Simplex versus duplex

A signal transmission may be simplex, half-duplex, or full-duplex.

In simplex transmission, signals are transmitted in only one direction; one station is a transmitter and the other is the receiver. In the half-duplex operation, both stations may transmit, but only one at a time. In full-duplex operation, both stations may transmit simultaneously. In the latter case, the medium is carrying signals in both directions at the same time.

Types

In general, a transmission medium can be classified as

- linear, if different waves at any particular point in the medium can be superposed;

- bounded, if it is finite in extent, otherwise unbounded;

- uniform or homogeneous, if its physical properties are unchanged at different points;

- isotropic, if its physical properties are the same in different directions.

There are two main types of transmission media:

- guided media—waves are guided along a solid medium such as a transmission line;

- unguided media—transmission and reception are achieved by means of an antenna.

One of the most common physical media used in networking is copper wire. Copper wire to carry signals to long distances using relatively low amounts of power. The unshielded twisted pair (UTP) is eight strands of copper wire, organized into four pairs.[1]

Twisted pair

Twisted pair cabling is a type of wiring in which two conductors of a single circuit are twisted together for the purposes of improving electromagnetic compatibility. Compared to a single conductor or an untwisted balanced pair, a twisted pair reduces electromagnetic radiation from the pair and crosstalk between neighboring pairs and improves rejection of external electromagnetic interference. It was invented by Alexander Graham Bell.[2]

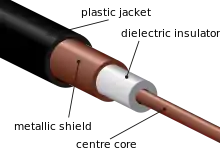

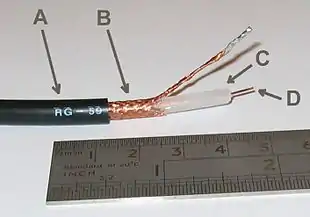

Coaxial cable

- Outer plastic sheath

- Woven copper shield

- Inner dielectric insulator

- Copper core

Coaxial cable, or coax (pronounced /ˈkoʊ.æks/) is a type of electrical cable that has an inner conductor surrounded by a tubular insulating layer, surrounded by a tubular conducting shield. Many coaxial cables also have an insulating outer sheath or jacket. The term coaxial comes from the inner conductor and the outer shield sharing a geometric axis. Coaxial cable was invented by English physicist, engineer, and mathematician Oliver Heaviside, who patented the design in 1880.[3]

Coaxial cable is a type of transmission line, used to carry high frequency electrical signals with low losses. It is used in such applications as telephone trunk lines, broadband internet networking cables, high-speed computer data busses, carrying cable television signals, and connecting radio transmitters and receivers to their antennas. It differs from other shielded cables because the dimensions of the cable and connectors are controlled to give a precise, constant conductor spacing, which is needed for it to function efficiently as a transmission line.

Optical fiber

Optical fiber, which has emerged as the most commonly used transmission medium for long-distance communications, is a thin strand of glass that guides light along its length. Four major factors favor optical fiber over copper: data rates, distance, installation, and costs. Optical fiber can carry huge amounts of data compared to copper. It can be run for hundreds of miles without the need for signal repeaters, in turn, reducing maintenance costs and improving the reliability of the communication system because repeaters are a common source of network failures. Glass is lighter than copper allowing for less need for specialized heavy-lifting equipment when installing long-distance optical fiber. Optical fiber for indoor applications cost approximately a dollar a foot, the same as copper.[4]

Multimode and single mode are two types of commonly used optical fiber. Multimode fiber uses LEDs as the light source and can carry signals over shorter distances, about 2 kilometers. Single mode can carry signals over distances of tens of miles.

An optical fiber is a flexible, transparent fiber made by drawing glass (silica) or plastic to a diameter slightly thicker than that of a human hair.[5] Optical fibers are used most often as a means to transmit light between the two ends of the fiber and find wide usage in fiber-optic communications, where they permit transmission over longer distances and at higher bandwidths (data rates) than electrical cables. Fibers are used instead of metal wires because signals travel along them with less loss; in addition, fibers are immune to electromagnetic interference, a problem from which metal wires suffer excessively.[6] Fibers are also used for illumination and imaging, and are often wrapped in bundles so they may be used to carry light into, or images out of confined spaces, as in the case of a fiberscope.[7] Specially designed fibers are also used for a variety of other applications, some of them being fiber optic sensors and fiber lasers.[8]

Optical fibers typically include a core surrounded by a transparent cladding material with a lower index of refraction. Light is kept in the core by the phenomenon of total internal reflection which causes the fiber to act as a waveguide.[9] Fibers that support many propagation paths or transverse modes are called multi-mode fibers, while those that support a single mode are called single-mode fibers (SMF). Multi-mode fibers generally have a wider core diameter[10] and are used for short-distance communication links and for applications where high power must be transmitted. Single-mode fibers are used for most communication links longer than 1,000 meters (3,300 ft).

Being able to join optical fibers with low loss is important in fiber optic communication.[11] This is more complex than joining electrical wire or cable and involves careful cleaving of the fibers, precise alignment of the fiber cores, and the coupling of these aligned cores. For applications that demand a permanent connection a fusion splice is common. In this technique, an electric arc is used to melt the ends of the fibers together. Another common technique is a mechanical splice, where the ends of the fibers are held in contact by mechanical force. Temporary or semi-permanent connections are made by means of specialized optical fiber connectors.[12]

The field of applied science and engineering concerned with the design and application of optical fibers is known as fiber optics. The term was coined by Indian physicist Narinder Singh Kapany, who is widely acknowledged as the father of fiber optics.[13]

Radio

Radio propagation is the behavior of radio waves as they travel, or are propagated, from one point to another, or into various parts of the atmosphere.[14] As a form of electromagnetic radiation, like light waves, radio waves are affected by the phenomena of reflection, refraction, diffraction, absorption, polarization, and scattering.[15] Understanding the effects of varying conditions on radio propagation has many practical applications, from choosing frequencies for international shortwave broadcasters, to designing reliable mobile telephone systems, to radio navigation, to operation of radar systems.

Different types of propagation are used in practical radio transmission systems. Line-of-sight propagation means radio waves that travel in a straight line from the transmitting antenna to the receiving antenna. Line of sight transmission is used to medium-range radio transmission such as cell phones, cordless phones, walkie-talkies, wireless networks, FM radio and television broadcasting and radar, and satellite communication, such as satellite television. Line-of-sight transmission on the surface of the Earth is limited to the distance to the visual horizon, which depends on the height of transmitting and receiving antennas. It is the only propagation method possible at microwave frequencies and above. At microwave frequencies, moisture in the atmosphere (rain fade) can degrade transmission.

At lower frequencies in the MF, LF, and VLF bands, due to diffraction radio waves can bend over obstacles like hills, and travel beyond the horizon as surface waves which follow the contour of the Earth. These are called ground waves. AM broadcasting stations use ground waves to cover their listening areas. As the frequency gets lower, the attenuation with distance decreases, so very low frequency (VLF) and extremely low frequency (ELF) ground waves can be used to communicate worldwide. VLF and ELF waves can penetrate significant distances through water and earth, and these frequencies are used for mine communication and military communication with submerged submarines.

At medium wave and shortwave frequencies (MF and HF bands) radio waves can refract from a layer of charged particles (ions) high in the atmosphere, called the ionosphere. This means that radio waves transmitted at an angle into the sky can be reflected back to Earth beyond the horizon, at great distances, even transcontinental distances. This is called skywave propagation. It is used by amateur radio operators to talk to other countries and shortwave broadcasting stations that broadcast internationally. Skywave communication is variable, dependent on conditions in the upper atmosphere; it is most reliable at night and in the winter. Due to its unreliability, since the advent of communication satellites in the 1960s, many long-range communication that previously used skywaves now use satellites.

In addition, there are several less common radio propagation mechanisms, such as tropospheric scattering (troposcatter) and near vertical incidence skywave (NVIS) which are used in specialized communication systems.

Digital encoding

Transmission and reception of data is typically performed in four steps:[16]

- At the transmitting end, the data is encoded to a binary representation.

- A carrier signal is modulated as specified by the binary representation.

- At the receiving end, the carrier signal is demodulated into a binary representation.

- The data is decoded from the binary representation.

See also

References

- Agrawal, Manish (2010). Business Data Communications. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 37. ISBN 978-0470483367.

- McBee, Jim; Barnett, David; Groth, David (2004). Cabling : the complete guide to network wiring (3rd ed.). San Francisco: SYBEX. p. 11. ISBN 9780782143317.

- Nahin, Paul J. (2002). Oliver Heaviside: The Life, Work, and Times of an Electrical Genius of the Victorian Age. ISBN 0-8018-6909-9.

- Agrawal, Manish (2010). Business Data Communications. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 41–43. ISBN 978-0470483367.

- "Optical Fiber". www.thefoa.org. The Fiber Optic Association. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- Senior, John M.; Jamro, M. Yousif (2009). Optical fiber communications: principles and practice. Pearson Education. pp. 7–9. ISBN 978-0130326812.

- "Birth of Fiberscopes". www.olympus-global.com. Olympus Corporation. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- Lee, Byoungho (2003). "Review of the present status of optical fiber sensors". Optical Fiber Technology. 9 (2): 57–79. Bibcode:2003OptFT...9...57L. doi:10.1016/s1068-5200(02)00527-8.

- Senior, pp. 12–14

- The Optical Industry & Systems Purchasing Directory. Optical Publishing Company. 1984.

- Senior, p. 218

- Senior, pp. 234–235

- "Narinder Singh Kapany Chair in Opto-electronics". ucsc.edu.

- H. P. Westman et al., (ed), Reference Data for Radio Engineers, Fifth Edition, 1968, Howard W. Sams and Co., ISBN 0-672-20678-1, Library of Congress Card No. 43-14665 page 26-1

- Demetrius T Paris and F. Kenneth Hurd, Basic Electromagnetic Theory, McGraw Hill, New York 1969 ISBN 0-07-048470-8, Chapter 8

- Agrawal, Manish (2010). Business Data Communications. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 54. ISBN 978-0470483367.