Transjordan in the Bible

Transjordan (Hebrew: עבר הירדן, Ever HaYarden) is an area of land in the Southern Levant lying east of the Jordan River valley. It is also alternatively called Gilead.

Etymology

In the Hebrew Bible, the term used to refer to the future Transjordan is Hebrew: עבר הירדן (Ever HaYarden), "beyond the Jordan". This term occurs, for example, in the Book of Joshua (1:14). It was used by people on the west side of the Jordan, including the biblical writers, to refer to the other side of the Jordan River.

In the Septuagint, the Hebrew: בעבר הירדן מזרח השמש (מזרחית לנהר הירדן), romanized: hay·yar·dên miz·raḥ, lit. 'beyond the Jordan towards the sunrise'[1] is translated to Ancient Greek: πέραν τοῦ Ιορδάνου,, romanized: translit. péran toú Jordánou,, lit. 'beyond the Jordan'.

The term was translated to Latin: trans Iordanen, lit. 'beyond the Jordan' in the Vulgate Bible.[2] However some authors give the Hebrew: עבר הירדן, romanized: Ever HaYarden, lit. 'beyond the Jordan', as the basis for Transjordan, which is also the modern Hebrew usage.[3] The prefix trans- is Latin and means "across" or beyond, so "Transjordan" refers to the land on the other side of the Jordan River. The equivalent Latin term for the west side is the Cisjordan - literally, "on this side of the [River] Jordan".

The term "East", as in "towards the sunrise", is also used in Arabic: شرق الأردن, romanized: Sharq al ʾUrdun, lit. 'East of the Jordan'.

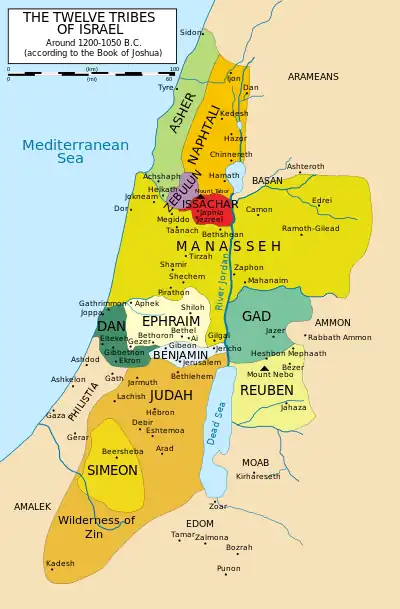

Transjordanian tribes

The Book of Numbers (chapter 32) tells how the tribes of Reuben and Gad came to Moses to ask if they could settle “beyond the Jordan”. Moses was dubious, but the two tribes promise to join in the conquest of the land, and so Moses grants them this region to live in. The half tribe of Manasseh are not mentioned until verse 33. David Jobling suggests that this is because Manasseh settled in land which previously belonged to Og, north of the Jabbok, while Reuben and Gad settled Sihon's land, which lay south of the Jabbok. Since Og's territory was not on the route to Canaan, it was "more naturally part of the Promised Land", and so the Manassites' status is less problematic than that of the Reubenites or Gadites.[4]

In the Book of Joshua (1), Joshua affirms Moses' decision, and urges the men of the two and a half tribes to help in the conquest, which they are willing to do. In Joshua 22, the Transjordanian tribes return, and build a massive altar by the Jordan. This causes the "whole congregation of the Israelites" to prepare for war, but they first send a delegation to the Transjordanian tribes, accusing them of making God angry and suggesting that their land may be unclean. In response to this, the Transjordanian tribes say that the altar is not for offerings, but is only a "witness". The western tribes are satisfied, and return home. Assis argues that the unusual dimensions of the altar suggest that it "was not meant for sacrificial use," but was, in fact, "meant to attract the attention of the other tribes" and provoke a reaction.[5]

Per the settlement of the Israelite tribes east of the Jordan, Burton MacDonald notes;

There are various traditions behind the Books of Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, and 1 Chronicles’ assignment of tribal territories and towns to Reuben, Gad, and the half-tribe of Manasseh. Some of these traditions provide only an idealized picture of Israelite possessions east of the Jordan; others are no more than vague generalizations. Num 21.21–35, for example, says only that the land the people occupied extended from Wadi Arnon to Wadi Jabbok, the boundary of the Amorites.[6]

Status

There is some ambiguity about the status of the Transjordan in the mind of the biblical writers. Horst Seebass argues that in Numbers "one finds awareness of Transjordan as being holy to YHWH."[8] He argues for this on the basis of the presence of the cities of refuge there, and because land taken in a holy war is always holy. Richard Hess, on the other hand, asserts that "the Transjordanian tribes were not in the land of promise."[9] Moshe Weinfeld argues that in the Book of Joshua, the Jordan is portrayed as "a barrier to the promised land,"[7] but in Deuteronomy 1:7 and 11:24, the Transjordan is an "integral part of the promised land."[10]

Unlike the other tribal allotments, the Transjordanian territory was not divided by lot. Jacob Milgrom suggests that it is assigned by Moses rather than by God.[11]

Lori Rowlett argues that in the Book of Joshua, the Transjordanian tribes function as the inverse of the Gibeonites (mentioned in Joshua 9). Whereas the former have the right ethnicity, but wrong geographical location, the latter have the wrong ethnicity, but are "within the boundary of the 'pure' geographical location."[12]

Other Transjordanian nations

According to the Hebrew Bible, Ammon and Moab were nations that occupied parts of Transjordan in ancient times.

According to Genesis, (19:37–38), Ammon and Moab were descendants of Lot by Lot's two daughters, in the aftermath of the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. The Bible refers to both the Ammonites and Moabites as the "children of Lot", which may also translate as “descendants of Lot”. Throughout the Bible, the Ammonites and Israelites are portrayed as mutual antagonists. During the Exodus, the Israelites were prohibited by the Ammonites from passing through their lands (Deuteronomy 23:4). In the Book of Judges, the Ammonites work with Eglon, king of the Moabites against Israel. Attacks by the Ammonites on Israelite communities east of the Jordan were the impetus behind the unification of the tribes under Saul (1 Samuel 11:1–15).

According to both Books of Kings (14:21–31) and Books of Chronicles (12:13), Naamah was an Ammonite. She was the only wife of King Solomon to be mentioned by name in the Tanakh as having borne a child. She was the mother of Solomon's successor, Rehoboam.[13]

The Ammonites presented a serious problem to the Pharisees because many marriages with Ammonite (and Moabite) wives had taken place in the days of Nehemiah (Nehemiah 13:23). The men had married women of the various nations without conversion, which made the children not Jewish.[14] The legitimacy of David's claim to royalty was disputed on account of his descent from Ruth, the Moabite.[15] King David spent time in the Transjordan after he had fled from the rebellion of his son Absalom (2 Samuel 17–19).

References

- "Joshua 1:16". Hebrew Bible. Trowitzsch. 1892. p. 155.

בעבר הירדן מזרח השמש (Image of p. 155 at Google Books)

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - "Joshua 1:15". The Septuagint Version of the Old Testament, with an English translation; and with various readings and critical notes. Gr. & Eng. S. Bagster & Sons. 1870. p. 281.

Image of p. 281 at Google Books

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - Merrill, Selah (1881). East of the Jordan: A Record of Travel and Observation in the Countries of Moab, Gilead and Bashan. C. Scribner's sons. p. 444.

Image of p. 444 at Google Books

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - David Jobling, The Sense of Biblical Narrative II: Structural Analyses in the Hebrew Bible (JSOTSup. 39; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1986) 116

- Elie Assis, "For it shall be a witness between us: a literary reading of Josh 22," Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 18 (2004) 216.

- MacDonald, Burton (2000). "Settlement of the Israelite Tribes East of the Jordan". In Matthews, Victor (ed.). EAST OF THE JORDAN: Territories and Sites of the Hebrew Scriptures (PDF). American Schools of Oriental Research. p. 149.

- Moshe Weinfeld, The Promise of the Land: The Inheritance of the Land of Canaan by the Israelites (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 54.

- Horst Seebass, "Holy Land in the Old Testament: Numbers and Joshua," Vetus Testamentum 56 (2006) 104.

- Richard S. Hess, "Tribes of Israel and Land Allotments/Borders," in Bill T. Arnold and H. G. M. Williamson (eds.), Dictionary of the Old Testament Historical Books (Downers Grove: IVP, 2005), 970.

- Moshe Weinfeld, "The Extent of the Promised Land – the Status of Transjordan," in Das Land Israel in biblischer Zeit (ed. G. Strecker; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1983) 66-68.

- Jacob Milgrom, Numbers (JPS Torah Commentary; Philadelphia: JPS, 1990), 74.

- Lori Rowlett, "Inclusion, Exclusion and Marginality in the Book of Joshua," JSOT 55 (1992) 17.

- "Naamah". Jewish Encyclopedia. 1906. Retrieved 2014-08-10.

- The identity of those particular tribes had been lost during the mixing of the nations caused by the conquests of Assyria. As a result, people from those nations were treated as complete gentiles and could convert without restriction.

- The Babylonian Talmud points out that Doeg the Edomite was the source of this dispute. He claimed that since David was descended from someone who was not allowed to marry into the community, his male ancestors were no longer part of the tribe of Judah (which was the tribe the King had to belong to). As a result, he could neither be the king, nor could he marry any Jewish woman (since he descended from a Moabite convert). The Prophet Samuel wrote the Book of Ruth in order to remind the people of the original law that women from Moab and Ammon were allowed to convert and marry into the Jewish people immediately.

External links

- Transjordan, Encyclopaedia Judaica, (c) 2008 The Gale Group, via Jewish Virtual Library, accessed 16 December 2019

Further reading

- Aharoni, Yohanan (1 January 1979). "The Transjordanian Highlands". The Land of the Bible: A Historical Geography. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 36–42. ISBN 978-0-664-24266-4.