Tinder

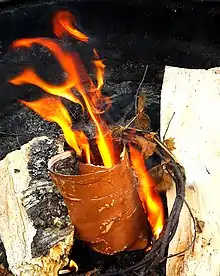

Tinder is easily combustible material used to start a fire. Tinder is a finely divided, open material which will begin to glow under a shower of sparks. Air is gently wafted over the glowing tinder until it bursts into flame. The flaming tinder is used to ignite kindling, which in turn is used to ignite the bulk material, to produce a fire.[1][2]

Tinder can be made of any flammable substance, as long as it is finely divided and has an open structure.

Technique

Any flammable material may be used as long as it is finely divided. As the tinder gets thinner, the surface area and edges increase, making it ignite more easily.

Wood tinder can be made by carefully shaving thin slivers off a larger piece. Another method which keeps these slivers together, is to make a feather stick. The driest wood, which makes the best tinder, is that of dead branches that have not yet fallen to the ground.

If a fire is to be lit by sparks rather than matches, char cloth, punkwood, fungus or down are commonly used to catch the sparks. However, fungi should be selected with care as some release toxic fumes on combustion. Char cloth can be made by placing plant-based fabric (usually cotton) in a tin box into a campfire; like charcoal, it is the product of anhydrous pyrolysis. It is very fragile, and should usually be prepared only in small quantities.

Pitchwood is the resinous wood which decays last from dead conifers. It can be found on the ground where conifer tree trunks have fallen and decayed. The parts of the deadwood that would form the knots in lumber, i.e. the places where branches entered the trunk, are impregnated with resin which has the combustibility of wood soaked in lighter fluid. Pitchwood can also be found in the stumps left in the ground when conifers die. These stumps contain spires of resin-impregnated wood, called fatwood, which can easily be lighted using only a single match or lighter. Pitchwood that has been shaved into small splinters is easy to ignite, and it does not absorb water, so it remains easy to ignite in any weather as long as the flame is sheltered from rain and wind. In the southeastern United States, pitchwood is known as "fat lighter" or "lighter'd" (a shortening of lighter-wood).[3]

Embers of burned paper, leaves and other sheetlike materials are easily carried off by air currents, where they can alight upon other objects and ignite them. In outdoor campfires, paper can be wadded up to reduce this hazard; wadded paper also burns more quickly.

Magnesium is sold in stores in shaved or bar form. Shavings burn white-hot, are impossible to smother with carbon dioxide or sand, and can ignite even wet kindling. Solid bars are impossible to ignite under normal conditions (and difficult even with a welding torch), and are thus very safe to carry. Magnesium powder and shavings are pyrophoric (they oxidise rapidly when exposed to the air). It is dangerous to carry pre-shaved magnesium — at best, it loses potency, at worst, it can spontaneously ignite and is then nearly unquenchable. Magnesium bars are sometimes sold with a length of ferrocerium cast into one edge.[4]

The gathering of tinder, and perhaps more importantly, its dry storage is one of the most critical aspects of many survival situations.

Materials

Materials used as tinder around the world include:[5]

- Small twigs (poor tinder but commonly available)[6]

- Paper, paper towels, toilet paper, etc.

- Dry pine needles, leaves or grass[7]

- Birch bark

- Dead, standing (usually one season old) goldenrod

- Cloth, lint, or frayed rope (if made from plant fibers and not treated with fire retardant)

- Char cloth

- Cotton balls, cotton swabs, tampons

- Some types of fungus, such as chaga and amadou (or horse's hoof fungus)

- Dry bread or knäckebröd and shoe polish

- Punk wood (in the process of rotting) or charred wood

- Bird down

- Fatwood, also known as rich pine or pine knot

- Fine-grade soap-coated steel wool

- Shaved magnesium or other alkaline earth metals[4]

- Specially prepared stringybark, known as morthi, used by the Kaurna people of South Australia[8]

References

- "Wild Wood Survival". Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- Uploaded on September 30, 2008 (2008-09-30). "Test Your Fire-Building IQ | Field & Stream". Fieldandstream.com. Archived from the original on 2008-09-19. Retrieved 2011-06-23.

- Ratliff, Donald E. Sr., Map, Compass and Campfire, Binford & Mort, Publishers, 1964, page 45.

- Cooper, Donald C. (2005). Fundamentals of search and rescue. National Association for Search and Rescue (U.S.) (illustrated ed.). Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 341. ISBN 0-7637-4807-2. Retrieved 14 Apr 2009.

- "Char Mastery: Charred Tinder How-To". Real World Survivor. 19 March 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- "Billy Goat Mountain Adventures" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-22. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- "Whipperleys". Archived from the original on 2022-03-05. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- Schultz, Chester (22 October 2018). "Place Name Summary 6/23: Brukangga and Tindale's uses of the word bruki" (PDF). Adelaide Research & Scholarship. University of Adelaide. Retrieved 16 November 2020.