Tigers in Korean culture

The tiger has been strongly associated with Korean people and Korean culture. It appears in not only the Korean foundation mythology but also in folklore, as well as a favorite subject of Korean art such as painting and sculpture. The mascot of the 1988 Summer Olympics held in Seoul, South Korea, is Hodori, a stylized tiger to represent Korean people.[1]

| Tigers in Korean culture | |

Minhwa (Korean folk painting) | |

| Korean name | |

|---|---|

| Hangul | 호랑이, 범 |

| Hanja | 虎郞이, none |

| Revised Romanization | horang-i, beom, ho |

| McCune–Reischauer | horang-i, pŏm, ho |

History

The oldest historical record about the tiger can be found in the myth of Dangun, the legendary founding father of Gojoseon, told in the Samguk Yusa, or the Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms. According to the myth, a bear and a tiger wished to become human beings. The bear turned into a woman by observing the commandments to eat only mugwort and garlic for 100 days in the cave. But the tiger could not endure the ordeal and ran off, failing to realize its wish.

There are 635 historical records about tigers in the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty.[2] The story of a tiger that began from a myth can be also found in daily life as well. For example, the 19th-century painting named "Sansindo" depicts the guardian spirit of a mountain leaning against a tiger or riding on the back of the animal. The animal is also known to do the errands for the mountain's guardian spirit which is known to wish for peace and the well-being of the village. So, the tiger was ordered by the spiritual guardian of the mountain to give protection and wish for peace in the village. People drew such paintings and hung them in the shrine built in the mountain of the village where memorial rituals were performed regularly. In Buddhism, there is also a shrine that keeps the painting of the guardian spirit of the mountain. Called "Sansintaenghwa", it is depiction of the guardian spirit of the mountain and a tiger.

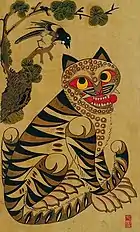

The painting "Jakhodo" (in leopard paintings, "Jakpyodo"; "pyo" means leopard) is about a magpie and a tiger. The letter "jak" means magpie; "ho" means tiger; and "do" means painting. Since the work is known to keep away evil influence, there is a tradition to hang the art piece in the house in the first month of the lunar calendar. On a branch of a green pine tree sits a magpie and the tiger (or leopard), with a humorous expression, looks up at the bird. The tiger in "Jakhodo" does not look anything like a strong creature with power and authority.

Kkachi horangi, paintings depicting magpies and tigers, was a prominent motif in the minhwa folk art of the Joseon period. Kkachi pyobeom paintings depict magpies and leopards. In kkachi horangi paintings, the tiger, which is intentionally given a ridiculous and stupid appearance (hence its nickname "idiot tiger" 바보호랑이), represents authority and the aristocratic yangban, while the dignified magpie represents the common people. Hence, kkachi horangi paintings of magpies and tigers were a satire of the hierarchical structure of Joseon's feudal society.[3][4]

They can be also found around the royal tombs. In front of the burial mound stands the stone tiger sculptures. People believed that tigers also safeguarded the tomb, the permanent home for the dead. The sacredness of the tiger was also utilized for holding rituals that pray for rain. According to the historical records of the early Joseon era, the head of a tiger was offered as the sacrificial offering when performing a ritual praying for rain while Joseon was under the reign of kings such as Taejong, Sejong, Munjong, and Danjong.

Gallery

Painting by Gim Hongdo

Painting by Gim Hongdo Joseon period folk painting depicting a tiger smoking pipe. The tiger had leopard patterns on its head.

Joseon period folk painting depicting a tiger smoking pipe. The tiger had leopard patterns on its head.

"Jakpyodo" painting Minhwa, depicting a leopard instead of a tiger

"Jakpyodo" painting Minhwa, depicting a leopard instead of a tiger

References

- 호랑이 [Horang-i (Tiger)] (in Korean). Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- "사냥-전통수렵 방법과 도구". 문화콘텐츠닷컴 (in Korean). Retrieved 14 August 2018.

『조선왕조실록』에 실린 호랑이 관련 기사는 모두 635건에 이른다.

- "까치호랑이". Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture. National Folk Museum of Korea. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- KOREA Magazine March 2017. Korean Culture and Information Service. 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.