The horse in Nordic mythology

The horse in Nordic mythology is the most important animal in terms of its role, both in the texts, Eddas and saga, and in representations and cults. Almost always named, the horse is associated with the gods Æsir and Vanir, with heroes or their enemies in Nordic mythology. The horse is more than just a means of transport, as it is at the heart of numerous fertility rituals in connection with the god Freyr. Closely associated with the cosmogony of the ancient Germanic-Scandinavians and with profound shamanic symbolism, this psychopomp is entrusted with the task of carrying the dead to Valhalla. The horse pulls the chariot of the sun and moon and lights up the world with its mane. It is linked to many vital elements, such as light, air, water and fire. The male horse is also highly valued in comparison with the mare.

This importance in the founding texts and sagas reflects the high value of the horse among Nordic peoples, as also attested by the rituals linked to its sacrifice, the consumption of its meat or the use of its body parts, reputed to bring protection and fertility. His bones were used as instruments of black magic in the sagas. Demonizing and combating equestrian traditions and rituals, such as hippophagy, was a key element in the Christianization of the Nordic regions of Germania, Scandinavia and Iceland.

Generalities

In archaeology, as in Prose Edda, the horse is the most important animal in Nordic mythology.[1] Sacrificial horses associated with deities are among the oldest archaeological finds in these regions.[2] The texts reflect the society and customs of the time, clearly showing, according to Marc-André Wagner, that the horse was considered a "double of man" and a "form of the powers", both in the founding texts, rites and mentality of the Germans.[3]

This is due to a worldview based on the perception of nature, which is at the origin of the myths. Horses (like gods, plants and people) embody the forces of the cosmos and nature.[4] In 1930, W. Steller postulated the existence of an original Germanic horse-god.[5] The first real study on the subject was Gutorm Gjessing's Hesten i forhistorisk kunst og kultus (1943), in which he develops the idea of the horse as an ancient symbol of fertility in Nordic mythology, in connection with the god Freyr. Secondly, he saw a connection with the Odinic cult of warrior death.[6]

Horses in texts

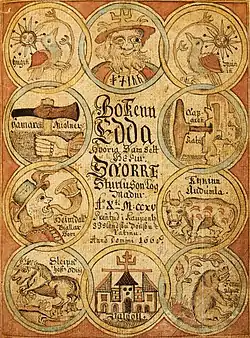

Written sources come mainly from the Prose Edda and the Poetic Edda, but also from the saga. Although they do not always contain many mythological elements, they do provide a precise idea of the cults paid to this animal and its importance for the ancient German-Scandinavians, and hence the reasons for its place in the founding texts. The Nafnaþulur, a form of mnemonic enumeration in Snorri Sturluson's prose Edda, provide a large number of horse names: Hrafn, Sleipnir, Valr, Lettfeti, Tjaldari, Gulltoppr, Goti, Soti, Mor, Lungr, Marr, Vigg, Stuffr, Skaevadr, Blakkr, Thegn, Silfrtoppr, Fakr, Gullfaxi, Jor, and Blóðughófi.[7]

Horses of the Aesir gods

Horses belonging to the Aesir gods are mentioned in the Grímnismál (30) and in the Gylfaginning (15). Gulltopp is attributed to the god Heimdall in Baldrs draumar, where the god rides this animal as part of the funeral procession to celebrate Baldr's cremation.[8][9]

In the Grímnismál

The eddic poem Grímnismál cites the following names:

Glad and Gyllir,

Gler and Skeidbrimir,

Sillfrintopp and Sinir,

Gisl and Falhofnir,

Gulltopp and Lettfeti;

On these mounts the Aesir

Ride every day

When they go to council,

At the root of Yggdrasill.

-Grímnismál (30)[10]

In the Gylfaginning

The Gylfaginning, in Snorri Sturluson's prose Edda, repeats this list, adding Sleipnir "He who glides", Odin's eight-legged horse; and Glen or Glenr.[Note 1]

Every day, the Aesir ride over the Bifröst bridge, also known as the Aesir Bridge. Here are the names of the Aesir horses: Sleipnir is the best, belonging to Odin and having eight legs. The second is Gladr, the third Gyllir, the fourth Glenr, the fifth Skeidbrimir, the sixth Silfrintoppr, the seventh Sinir, the eighth Gisl, the ninth Falhófnir, the tenth Gulltoppr, the eleventh Léttfeti. Baldr's horse was burned with him; and Thor walks to judgment.

Sleipnir

Sleipnir holds a very special place in mythological texts, being both the best described and most frequently mentioned of the Aesir horses. Sleipnir means "glider".[12] It appears in Grímnismál,[13] Sigrdrífumál,[14] Baldrs draumar,[15] Hyndluljóð[16] and Skáldskaparmál.[17] This eight-legged animal could move over the sea as well as in the air, and was the son of the god Loki and the powerful stallion Svaðilfari.[18] "Best of all horses" and fastest of all, according to Snorri Sturluson,[19] he became Odin's mount, riding him to the region of Hel and lending him to his messenger Hermóðr to accomplish the same journey;[20] however, the god used him mainly to cross the Bifröst bridge to reach the third root of Yggdrasil, where the council of the gods was held. The Prose Edda gives many details on the circumstances of Sleipnir's birth, and specifies, for example, that he is gray in color. He is also the ancestor of the Grani horse.

Other divine and cosmogonic horses

Other horses linked to divinities or playing a role in cosmogony are mentioned in Nordic mythology. The Gylfaginning (35) reveals the origin of Sleipnir and mentions the horse Svadilfari at length. The horse was also frequently the object of admiration in the Poetic Edda, for its shape and speed. Kennings have been found comparing ships and horses, notably in the Poetic Edda, section of the Song of Sigurd, the Dragon Slayer (16). Árvakr and Alsviðr ("Early riser" and "Very swift") are the two horses that pull the goddess Sól's chariot across the sky every day,[21][22] their manes emitting daylight. Skinfaxi and Hrímfaxi ("Shining mane" and "Mane of frost") are, according to Snorri Sturluson, two other cosmogonic horses. One belongs to the personification of night, Nótt, who rides him during the night, the other to the personification of day, Dagr, who rides him during the day.[22] The first drools foam that becomes morning dew, while the second lights up the world with its mane.[23]

In the Nafnaþulur of the Prose Edda, Blóðughófi, sometimes anglicized as Blodughofi "bloody hoof",[24] was a horse capable of passing through fire and darkness, and belonged to Freyr.[25][26] In the Skírnismál of the Poetic Edda, Freyr gave Skírnir a horse capable of running through fire to Jötunheimr to meet the giantess Gerðr; the animal was not named, but it was most likely Blóðughófi.[27] Gullfaxi ("Golden Mane") was, in Skáldskaparmál (17), a horse originally belonging to the giant Hrungnir. After defeating the giant, Thor gave it to his son Magni as a reward for his help.[17]

Hófvarpnir "He who throws his hooves"[Note 2][28][29] or "He who kicks his hooves"[30] was the horse of the goddess Gná, capable of moving through the air and over the sea.[30] Mentioned in the prose Edda, he was the son of Hamskerpir[Note 3] and Garðrofa, "Breaker of Fences".[31]

I don't fly

Though I think

To cross the skies

Over Hofvarpnir

The one Hamskerpir had

With Garðrofa

-Gylfaginning (35)[32]

Jacob Grimm noted that Gná was not considered a winged goddess, but that her mount Hófvarpnir may have been a winged horse, like Pegasus in Greek mythology.[33] John Lindow added that Hamskerpir and Garðrofa are totally unknown to other sources of Nordic mythology, and that if they had an associated myth, it may not have survived.[31]

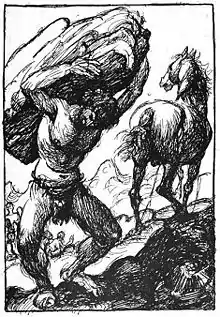

Svadilfari or Svaðilfari[Note 4] "He who makes arduous journeys,"[29][34] or "He who makes unhappy journeys"[35] is the stallion who begot Sleipnir with Loki transformed into a mare according to the Hyndluljód (40). Snorri's Gylfaginning (42) states that he belongs to the giant master builder and contributed to the construction of Asgard.[19]

The Valkyrie horses are described in the Helgakvida Hjörvardssonar:

Quand les chevaux dressaient la tête, la rosée, de leurs crinières

tombait dans les vallées profondes

— Helgakvida Hjörvardssonar (28)[36]

This description recalls Hrimfaxi.[37]

Horses of heroes and sagas

The horse features prominently in the sagas and heroic tales of the Poetic Edda. In the Swedish saga of the Ynglingar, the king can give three very precious things, which are, in order: a good horse, a golden saddle and a fine ship.[38] Freyfaxi, "Freyr's Mane", is the horse dedicated to the god Freyr, belonging to the protagonist of the Hrafnkell saga. He had sworn that he alone would ride it, and that he would kill anyone who tried to climb onto it. The breaking of this oath is a major plot element in the saga. When his neighbor's son rides Freyfaxi to retrieve his runaway sheep, Hrafnkell remains true to his oath and kills him.[39]

Grani is a gray horse descended from Odin's mount Sleipnir. It is captured and ridden by the hero Sigurd (or Siegfried) in the Völsunga saga (13) on the advice of an old man who is in fact the god Odin in disguise.[40] This horse then accompanies Sigurd on all his adventures. Grani possesses marvelous powers, great strength and remarkable intelligence,[41] as he proved when he broke through the ring of flames surrounding the valkyrie Brunhilde (27),[42] then mourned his master's death with his wife Gudrun. In Richard Wagner's opera Der Ring des Nibelungen, Grane is the name of Brunehilde's horse. Goti, another horse mentioned in the Sigurd legend, is the mount of Sigurd's blood brother, Gunther. Goti flees the inferno surrounding the valkyrie Brunhilde, forcing Sigurd to lend his own mount, Grani, to Gunther.[43]

Other horses

Snorri Sturluson mentions several horses belonging to kings and highlights their passion for these animals on numerous occasions. According to Heimskringla,[7] the Norwegian king Eadgils loved generous steeds and fed the two best of his time. One was named Slöngvir, the other Hrafn. The mare he took after the death of King Ala gave birth to another destier with the same name. Adils presented Hrafn to Godgest, King of Heligoland, but the chieftain rode her one day, unable to stop her, and fell to his death.[44]

Kings Allrek and Kirek tamed steeds and surpassed all others in the art of horsemanship. They vied with each other to see who could win through skill as a rider or beauty of mount. One day, the two brothers, carried away by the ardor of their horses, didn't return. Only their corpses were found. They had fallen victim to their favorite passion.[45] Other traces of horses from Nordic mythology can be found in the name of the English hero Hengist (meaning "stallion") and his brother Horsa, "horse".[2]

Analysis

According to the Prose Edda, only the male gods owned horses; the twelve Aesir gods shared eleven, and Thor was the only one without a horse, since he made the journey across the Bifröst bridge on foot.[46] The highly "humanized" Scandinavian gods seem to have the same concerns as men on earth, for a good horse is indispensable even to a god.[47] Most Aesir horses were not associated with any particular deity, apart from Sleipnir and Gulltopp. There is no other written information on these mounts, apart from that provided by the etymology of their names

Etymology of Aesir horse

Several translations of the Aesir horses' names from Old Norse have been proposed, notably in French by Régis Boyer and François-Xavier Dillmann, in German by Rudolf Simek, and in English by John Lindow and Carolyne Larrington. Glad, or Glaðr means "Joyful"[28][48][49] or "Radiant";[34][29] Gyllir "Golden"; Glær "Clear"[29][28] or "Transparent";[48][49] Skeidbrimir or Skeiðbrimir "He who snorts during the race"[28][34] or "He who snorts during the race";[29] Silfrintopp or Silfrintoppr "Silver toupet" or "Silver mane" ; Sinir "Nervous";[28][29] Gísl "Radiant";[34][49][29][48][28] Falhófnir "He whose hooves are covered with hair"[29][34][48] or "He whose hooves are light";[28][49] Gulltopp or Gulltoppr "Golden head" or "Golden mane",[9] and Léttfeti "Light hoof".

Disdain for the mare

A constant feature of Nordic mythology texts is their disdain for the mare, which explains the shame Loki suffered when he transformed himself into a mare to seduce Svadilfari and give birth to Sleipnir.[50] This contempt is echoed in the Skáldskaparmál, where Hrungnir, the clay man conceived by the giants, has the heart of a mare: frightened, he urinates himself when he sees Thor.[51] In the sagas, the mare is a symbol of passive homosexuality, and the mere use of this name to designate a man became an insult.[52] This peculiarity is to be found in the conception of German-Scandinavian society, which is rather patriarchal and warlike.[53] The exchange of insults in Helgakvida Hjörvardssonar[54] highlights the symbol of domination and power represented by the stallion's phallus, while the mare represents a raped person or a passive homosexual.[55] This contrasts with ancient Celtic and Greek traditions of the "mare-goddess".[56] Freyja is associated with many animals (cat, hawk) and sometimes nicknamed Jodis, "Dise-stallion",[57] but there is no association of a mare with a deity in Nordic mythology.[56]

Archaeological and iconographic sources

The horse is also present in artistic representations from the periods of Nordic mythology. During the Bronze Age, a Swedish rock engraving shows a figure whose phallus ends in a horse's head;[58] it could be dedicated to Odin or Freyr[59] and constitutes the earliest known attestation of the fertility cult in these regions.[60] Another possible attestation, found at Faardal in Norway, takes the form of a generously-shaped female statuette accompanied by a snake-bodied horse. This could be a female fertility deity or a priestess presiding over a cult of this type with the horse.[61]

It is generally accepted that Sleipnir is depicted on several Gotland pictured stones from around the 7th century, including the Tjängvide stone and the Ardre VIII stone.[62] One of the possible interpretations of these Gotland stones, due to their phallic or "keyhole" shape, is also the cult of fertility.[63][64] The presence of horses in the texts of runic amulets refers to the same function.[65]

Trundholm solar chariot

Proof of the ancient association of the horse and the Sun among Germanic-Scandinavian peoples is provided by the discovery in Denmark of an ancient bronze, known as the "Trundholm solar chariot", representing the Sun pulled by a horse and dating from around 1,400 BC. The animal pulls the star during the day (or summer), in opposition to the boat it uses at night (or winter), according to a dualism also evidenced by Bronze Age rock engravings.[66]

Ehwaz

The Ehwaz rune is entirely devoted to the horse in the futhark alphabet, but the name itself is not associated with equestrian myths. The shapes of the bracteates with horses themselves seem unrelated to the text they contain. On the other hand, the rune "e" in "Ehwaz" is itself directly related to fertility,[2] linking the rune to kings, deities and the supernatural realm rather than to a warrior function.[67]

Symbolism

As in all other traditions,[68] the horse has varying meanings in Nordic mythology. The ancient Scandinavian peoples were a mystical, horse-riding civilization, where shamanism held great importance, and it's natural that they attributed many powers to the horse. The horse is neither inherently good nor evil, as it is associated with gods and giants alike, with night (through Hrimfaxi) and day. The horse is a central mediator in Nordic society, and may have played an intermediary role between wild and domestic animals, since large herds of wild horses were still to be found, at least until the 10th century. It could be ridden across plains as easily as over mountainous terrain, a feature that may have contributed to its special place in the founding texts.[22]

The Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung, who carried out several studies on the symbolism of the horse in psychoanalysis, notes an intimate relationship between rider and horse in fairy tales and legends. The hero and his steed "seem to him to represent the idea of man with the instinctual sphere subject to him".[69] Legends attribute to the horse characters that he believes are psychologically linked to the unconscious of man, for horses are endowed with clairvoyance, have mantic faculties and can also see ghosts. The horse's hoof, often anthropomorphized, has an important symbolic quality, and he shows this in critical moments: during Hadding's abduction, Sleipnir's hoof suddenly appears under Wotan's cloak, for example, and Jung sees in this the irruption of a symbolized unconscious content.[70] There are parallels between Celtic and Viking beliefs. In the Laxdoela saga, written in Iceland, the hero Kjartan (whose grandmother is Irish) rejects white horses with red ears.[71] In Celtic literature, this is the color of horses from the Otherworld.

Vehicle and psychopump

One of the earliest symbolism of the horse seems to be, as in most religions, that of a vehicle driven by the will of man, as shown by Odin riding Sleipnir between the nine worlds. The rune raido, present in the futhark, means both "ride" and "journey". In his thesis, Marc-André Wagner points out that the notion of movement, in the sense of vital impetus, is most frequently present in the etymology of German equestrian terms.[72] The horse is seen as the link between the two worlds, that of the living and that of the dead,[73] which defines its place as a sacred animal. He adds that the horse's role as guide to the souls of the dead (" Psychopump ") abounds in the texts, particularly when Hermodr visits Hel's home on horseback.[74]

Carl Gustav Jung, who also notes the psychopompic aspect of Sleipnir and the Valkyries' mounts, sees the horse as one of the most fundamental archetypes of mythology, close to the symbolism of the tree of life. Like the Tree of Life, it links all levels of the cosmos: the earthly plane, where it runs, the subterranean plane, with which it is familiar, and the celestial plane.[75] Ulla Loumand cites Sleipnir and the flying horse Hófvarpnir as "prime examples" of intermediate horses between earth and sky, between Ásgarðr, Miðgarðr and Útgarðr, between the mortal world and the underworld in Nordic mythology. This makes the horse the best animal for guiding the dead on their journey to the other world, its very first quality being mobility.[22]

Life and fertility

According to Jean Clottes and André Leroi-Gourhan, the association of the horse with phallic cults may date back to Indo-European prehistory,[76] but this cult is only attested in the Germanic area in the Bronze Age, with other animals also being involved.[77] As a phallic symbol, the horse (only the male) is a symbol of sexual domination and fertilizing power.[78] Among the Vanir gods, the horse appears as a being that maintains and preserves life. This association also encompasses the notion of sexual energy, present today in Germanic etymology.[79]

Death

The horse is associated with death in many ways: it announces it, gives it and protects the deceased. This symbolism should be seen in the broader context of the Nordic pagan vision of death as part of a whole and a cycle,[80] in association with hippomancy, divination using horses.[81] Many horses were servants or harbingers of death. The Vatnsdœla saga tells of Thorkell Silfri's dream of a red horse. His wife sees this as a threat of death to come, for "this horse is called Marr, and marr is the guardian spirit (fylgja) of a man". Thokell Silfri dies shortly afterwards.[82] In the Sturlungar saga, Sighvatr Sturluson dreams that his horse Fölski enters the room where he is, devours all the food and plates, and asks why he was not invited. Régis Boyer also interprets it as a death omen.[83] In the Svarfdœla saga, written around 1300, Klaufi, who had been murdered, reappears riding a grey horse harnessed in the air and foretells his cousin's death, which inevitably comes true.[84]

Fire and light

Horses are also linked to the symbolism of fire and light, and by extension to that of lightning; thus, Sigurd jumped over the Waterlohe inferno surrounding Brunehild "mounted on Grani, the horse of thunder, which descends from Sleipnir and which alone does not shrink from fire", says Carl Gustav Jung.[75] Freyr's horse could ride through fire. Horses are frequently involved in pulling the sun and lighting up the world: Skinfaxi lights up the world with his mane of light, Árvak and Alsviðr pull the sun's chariot.

Water

The ancient Scandinavians of the Baltic and North Seas also put forward a close link between horse and water, and according to Marlene Baum, they were the first people to do so. This association can be seen in kenning, meaning "wave horse", which referred to the longest boats used by the Vikings.[85]

Air

The aerial symbolism of the horse is highlighted many times, notably through Sleipnir, whose eight feet enabled him to run on land as well as in the air, and who also possessed a special link with the wind and, by extension, with speed.[86] Jung saw in Sleipnir an "anguish impulse, but also a migratory impulse, the symbol of the wind that blows across the plains and invites man to flee from home",[87] and the clouds were described as the horses of the valkyries.

Horses in worship

Prior to Christianization, the horse was at the heart of numerous cultural practices. The vast majority were related to maintaining fertility.[88] Considered a link between the spirits of the earth, the earth itself, and mankind, according to Marc-André Wagner, the horse embodied the cosmic vital cycle, and its regular sacrifice was intended to maintain it. Its head reveals a close link with the notion of royalty[89] and as the embodiment of the fertilizing principle.[90] The horse's skull was used in apotropaic rituals.[91]

Fertility cults

The vast majority of equine cults involve agrarian rites of fecundity and fertility, with the horse largely eclipsing other animals in this role.[92] Archaeological evidence is scarce, but the many surviving forms in Germanic rural traditions attest to their existence in earlier times.[93] Most of these rituals show a close relationship with the god Freyr. According to the Flateyjarbók, King Óláfr discovered a pagan shrine in Trondheim, Norway, with horses consecrated to the god for sacrifice, which he was forbidden to ride.[94] Further evidence of this association can be found in the Hrafnkell saga, where Freyfaxi ("Freyr's mane") is dedicated to the god.[67]

Fertility sacrifice

Horses were traditionally sacrificed for protection and fertility rituals, and their meat was then eaten.[95] The strength of this animal, considered a fertility genie, was believed to be transmitted to its owner or executioner. The mainland Vikings of Gern sacrificed white horses and regularly consumed their meat.[95]

Völsa þáttr

The Völsa þáttr, a 14th-century text, reveals a close association between the horse and this ancient fertility cult. A Norwegian farming couple prepare their horse to eat after its death, following pagan tradition. They keep the animal's penis, regarding it as a god (this is a partial presentation, as the object is actually an offering to Mörnir). Every evening, the penis is passed from hand to hand and an incantatory stanza is recited, until the day King Olaf finds out about it and converts the whole household to Christianity. Régis Boyer and other specialists believe that the Völsa þáttr bears witness to "very ancient ritual practices ",[96] and emphasizes the sacred nature of the horse, which is confirmed by numerous other sources, as well as its association with Freyr.[97][98] It would seem that the preservation and veneration of the animal's penis was common practice right up to christianization (and continued in Norway until the 14th century), and that either the sex itself or the deity to whom it was offered were purveyors of abundance and fertility, as part of an agrarian rite to regenerate nature. According to this belief, the fertilizing power attributed to the horse influenced the growth of vegetation.[99]

Stallion fighting

The Icelandic practice of stallion fighting is documented in the sagas.[100] Régis Boyer sees in this brutal form of entertainment[101] a possible unconscious survival[102] of the cult of Freyr.[103] These fights continued throughout Scandinavia until the 19th century,[104] and ethnological evidence links them to a fertility rite.[105]

Funerary worship

Archaeological findings, particularly in Iceland in the 10th century, suggest that horses played an important role in burial practices: horses endowed with fabulous powers are mentioned in the founding texts of both Valhalla and Hel, confirming their status as psychopomp animals.[22] Horses found buried in Iceland most frequently appear to have been buried individually with their master, sometimes saddled and bridled, presumably to carry the latter to Valhalla. Although it's not certain that horses were the most frequently ritually sacrificed animal among the ancient Scandinavians, there's every indication that a large number were sacrificed and eaten at funeral feasts.[22]

Shamanism and sorcery

The horse is the animal of shamanism, the instrument of trances and a mask during initiation rituals, but also a demon of death and an instrument of black magic through its bones. According to the Egill saga, the niðstöng is a stake into which the skull of a horse is driven, which is then pointed in the direction of the victim and cursed. The exact meaning of the niðstöng, however, is difficult to ascertain.[22] The Vatnsdæla saga also mentions a stake with a horse's head.[22] These rites have not been taken up by neopaganist movements such as Heathenry.[89]

Sacred weddings and royalty

Fragments of information suggest that white horse sacrifice was practiced as part of a sacred marriage.[95] In the Heimskringla, the saga of Haakon I of Norway recounts how he had to drink a broth made from the flesh of a ritually sacrificed horse. This story fits in with the Germanic perception of the horse as a symbol of sovereignty, and the need for the king to be ritually linked to his kingdom. The rites of fertility and abundance were a way for the sovereign to ensure the good health of the lands over which he reigned.[67]

Christianization

During the Christianization of Germania and Scandinavia, all rites and traditions associated with the horse were combated by the Christian authorities in order to promote religious conversion. According to specialists such as Ulla Loumand and François-Xavier Dillmann, the consumption of horse meat after the animal's sacrifice was a custom that the evangelizers of Germania, Scandinavia and Iceland tried to eradicate.[22] Pope Gregory III banned hippophagy in 732, denouncing it as a "filthy practice".[106] In Iceland, one of the first prohibitions issued by the Church was that of hippophagy.[107] At first, the Pope demanded that local populations who had become Christians abandon this practice, which was assimilated to paganism, before reversing this demand and tolerating it. Rituals linked to funeral offerings of the horse were also prohibited, and at the same time, the animal was eliminated from the religious sphere, as evidenced by the ban on parades and rogations on horseback.

Horse demonization

Throughout pagan times, and especially among the ancient Germans, the horse was considered sacred and of divine essence, but now it has acquired a demonic and evil character. The Christian church made the gods it worshipped seem like demons. According to Jacob Grimm, people were not so quick to abandon their belief in the old gods. They assigned them another place, and, without forgetting them altogether, hid them behind the new God, so to speak. Odin came at the head of his wild hunt, and was later gradually replaced by the Devil in popular belief. Among the animals, the horse was mainly dedicated to Odin. The people then attributed Odin's horse to the Devil; they believed that he and his followers could sometimes take its form; that sometimes, in certain circumstances, he could change a man into a horse, to be transported by him.[108] Christianization and the struggle against pagan practices associated with the horse led to a modification of its symbolism among the peoples of the ancient Nordic religion. The horse was associated with sin in the preaching of clerics, although its value remained positive in mystical bestiaries. Belief in the horse's apotropaic and beneficial virtues persisted, notably through organotherapy, but the animal acquired a dark, negative image, as evidenced by the horses mentioned in Nordic and Germanic folklore, such as the Danish Helhest, which spread pestilence, the German Schimmel Reiter, which destroyed dykes during storms, and the Swedish Nixie, which drowned riders riding it.

Representations in Art

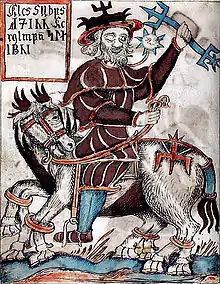

Sleipnir is depicted on several old Icelandic parchments, notably from the 18th century. In the 19th century, horses from Nordic mythology featured in the works of Norwegian painter Peter Nicolai Arbo.

18th-century Icelandic manuscript SÁM 66, depicting Odin and Sleipnir; now in the possession of the Árni Magnússon Institute in Iceland.

18th-century Icelandic manuscript SÁM 66, depicting Odin and Sleipnir; now in the possession of the Árni Magnússon Institute in Iceland. An illustration of Odin riding Sleipnir, in an 18th-century Icelandic manuscript of the "Prose Edda", source: Danish Royal Library.

An illustration of Odin riding Sleipnir, in an 18th-century Icelandic manuscript of the "Prose Edda", source: Danish Royal Library._-_Nationalmuseum_-_18255.tif.jpg.webp) The valkyries on their cloud horses, by Peter Nicolai Arbo.

The valkyries on their cloud horses, by Peter Nicolai Arbo.

Survival in folklore

Nordic place names refer to the horse, such as the two islands of Hestur and Koltur, whose names mean "horse" and "foal" respectively. Equine fertility cults can be found in German folklore with the Schimmelreiter, in Sweden with Julhäst, or Jul horses (equine-shaped cakes traditionally made at Christmas time),[109] in Alsace with the Pentecost riders,[110] and just about everywhere with the survival of agrarian offerings, blessings and horse races around Christmas or in May, to celebrate the arrival of summer.[111] Olaus Magnus described an equestrian joust celebrating May 1st and the victory of summer over winter.[112] The apotropaic use of horse body parts (skull,[113] whole head on house beams,[114] mare's placenta, skin[115]) to promote fertility continued long after Christianization, until the early 20th century.[116] Jacob Grimm noted the Lower Saxon tradition of decorating roof timbers with the heads of wooden horses, pointing out that they would protect against evil:[117] the same tradition was found in Hamburg, Reichenau (in the 10th century), Vindaus (Norway) and throughout Scandinavia in Viking times.[118] According to Marc-André Wagner, these popular traditions probably mirrored the equine cults of Nordic paganism.[90]

According to Jacob Grimm, the goddess of the underworld, Hel, possessed a "three-legged" mount, which survives in Danish folklore in the form of the Helhest, or "three-legged horse of hell", which goes to cemeteries to fetch the dead and spread pestilence.[119] However, Régis Boyer assures that there is no trace of this mount in the sources of Nordic mythology, and that it is essentially a matter of folklore.

According to Icelandic folklore, Sleipnir is the creator of the Ásbyrgi canyon, which he shaped into a horseshoe[120] with one blow of his hoof. Sleipnir seems to be the only horse in Nordic mythology to have survived under its own name, as Odin's mount on the wild hunt. In Mecklenburg, in the 16th century, a popular harvest song dedicated the last harvested sheaf to Odin's horse.[121] James George Frazer also notes numerous connections between the horse and the "spirit of wheat".[122]

Popular culture

Nordic equine myths and their symbolism are abundantly reproduced in popular culture. These horses probably inspired Tolkien to create the fictional cavalry of Middle-earth. Shadowfax is very close to Sleipnir, both symbolically and etymologically. The names of the horses of the lords of the kingdom of Rohan also resemble those of Nordic mythology.[123]

Notes

- Glen is mentioned instead of Glær in Codex Wormianus and Codex Trajectinus. Codex Upsaliensis, on the other hand, mentions neither.

- This literal translation could mean that the horse is kicking (according to Simek) or moving fast (according to Dillmann).

- According to John Lindow, the name Hamskerpir has no precise meaning.

- The spelling varies from manuscript to manuscript: Svaðilfari, Svaðilferi, Svaðilfori or Svaðilfǫri.

References

- Jennbert 2011, p. 122

- McLeod & Mees 2006, p. 106

- Wagner 2005, p. 4° de couverture

- Wagner 2005, pp. 10–11

- W. Steller, Phol ende Wotan, zfvk 40, 1930 (in French), pp. 61-71

- Gjessing 1943, p. 5-143

- Snorri Sturluson (2009). The Prose Edda. BiblioBazaar. pp. 209–212. ISBN 978-0-559-13108-0..

- Société des études germaniques (1954). Études germaniques. Vol. 9–10. Didier-Érudition. p. 264.

- Lindow 2002, p. 154

- Thorpe, Benjamin (1866). Edda Sæmundar Hinns Froða: The Edda Of Sæmund The Learned. Londres: Trübner & Co.

- Brodeur, Arthur Gilchrist (1916). Snorri Sturluson: The Prose Edda. New York: The American-Scandinavian Foundation.

- Orchard 1997, p. 151

- Larrington 1999, p. 58

- Larrington 1999, p. 169

- Larrington 1999, p. 243

- Larrington 1999, p. 258

- Faulkes 1995, p. 77

- Faulkes 1995, p. 35

- Faulkes 1995, pp. 35–36

- Faulkes 1995, pp. 49–50

- Simek 2007, pp. 10–11

- Loumand 2006, pp. 130–134

- Boyer 2002, pp. 519–520

- Sturluson, Snorri (2005). The Prose Edda: Translated with an Introduction and Notes by Jesse L. Byock. New York: Penguin Books.

- Schayes, Antonin Guillaume Bernard (1858). La Belgique et les Pays-Bas, avant et pendant la domination romaine,. Vol. 1. Emm. Devroye. p. 251.

- Turner, Patricia; Russell Coulter, Charles (2001). Dictionary of ancient deities. New York: Oxford University Press US. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-19-514504-5.

- Leonie Picard, Barbara (2001). Tales of the Norse Gods: Oxford Myths and Legends. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-19-275116-4.

- Rudolf Simek, Dictionnaire de la mythologie germano-scandinave, 1996.

- Snorri Sturluson (2003). François-Xavier Dillmann: L'Edda : Récits de mythologie nordique.

- Snorri Sturluson (2005). The Prose Edda: translated by Jesse Byock. Penguin Classics. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-14-044755-2.

- Lindow 2002, p. 147

- Byock, Jesse (2005). The Prose Edda. Londres: Penguin Classics. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-14-044755-2.

- Grimm 1883, pp. 896–897

- Boyer 2002

- Orchard 1997

- Boyer 2002, pp. 281–282

- Wagner 2005, p. 48

- Snorri Sturluson, Ynglinga saga

- Boyer 1987

- Magnússon, Eiríkr (2008). The Story of the Volsungs. Forgotten Books. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-60506-469-7.

- Tremain, Ruthven (1982). The animals' who's who : 1,146 celebrated animals in history, popular culture, literature, and lore. Londres: Routledge and Kegan Paul. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-7100-9449-0.

- "The story of the Volsungs (Völsunga saga) Chapter XXVII : The Wooing of Brynhild". omacl.org. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- Rosenberg, Donna (1994). World mythology : an anthology of the great myths and epics. NTC Pub. Group. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-8442-5767-9.

- Académie royale des sciences, des lettres et des beaux-arts de Belgique (1845). Bulletins. Vol. 12. M. Hayez. p. 181.

- Académie royale des sciences, des lettres et des beaux-arts de Belgique 1845, pp. 175–176

- "Raido". nordic-life.org/nmh. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- Alexandra Kelpin. "Le cheval islandais". Tempus Vivit. A Horseman. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- Larrington 1999

- Lindow 2002

- Wagner 2005, p. 31

- Snorri Sturluson, Skáldskaparmál, translation from Dillmann 2003, p. 113

- Wagner 2005, p. 33

- Wagner 2005, p. 34

- Helgakvida Hjörvardssonar, translated by Boyer 2002, pp. 281–182

- Wagner 2005, p. 35

- Wagner 2005, p. 36

- Régis Boyer, La Grande déesse du Nord, Berg international, 1995, p. 114

- Gossina, G. (1936). Die deutsche Vorgeschichte (in German). Leipzig. p. 105.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gossina 1936, pp. 104–106.

- Wagner 2005, p. 40.

- Gjessing 1943, pp. 12–13.

- Lindow 2002, p. 277

- en. Erik Nylen et Jan Peder Lamm, Stones, Ships and Symbols. The picture stones of Gotland from the Viking age and before, Stockholm, 1988, p. 12; 171

- de. B. Arrhenius, « Tür der Toten » dans Frühmittelalterliche Studien 4, 1970, p. 384-394

- McLeod & Mees 2006, p. 105

- Boyer 1997, p. 32.

- McLeod & Mees 2006, p. 107

- Wagner 2005, pp. 21–22

- Jung 1993, p. 456

- Jung 1993, p. 460

- J. Renaud, Les Vikings et les Celtes

- Wagner 2005, p. 23

- Wagner 2005, p. 89

- Wagner 2005, p. 89, citant le Gylfaginning, chap. 49

- Jung 1993

- Clottes, Jean; Lewis-Williams, David (1996). Les chamanes de la préhistoire: transe et magie dans les grottes ornées. Arts rupestres (in French). Paris: Seuil. p. 72. ISBN 2-02-028902-4. BNF: 36157930h..

- Wagner 2005, p. 39

- Wagner 2005, p. 58

- Wagner 2005, p. 26

- Wagner 2005, p. 61

- Wagner 2005, p. 63

- Boyer 1987, p. 1037

- Boyer 1979, p. 382

- Svarfdœla saga, chap. 23, cited by Claude Lecouteux, Fantômes et revenants au Moyen Âge, Paris, 1996, pp. 101-102

- Baum, Marlene (1991). Das Pferd als Symbol: zur kulturellen Bedeutung einer Symbiose (in German). Francfort-sur-le-Main: Fischer. ISBN 978-3-596-10473-4.

- Renauld-Krantz (1972). Structures de la mythologie nordique. G.-P. Maisonneuve & Larose. p. 103.

- Bouttes, Jean-Louis (1990). Jung : la puissance de l'illusion: La Couleur des idées. Paris: Seuil. p. 94. ISBN 978-2-02-012101-9.

- McLeod & Mees 2006, p. 108

- Rhys Mountfort, Paul (2003). Nordic Runes: Understanding, Casting, and Interpreting the Ancient Viking Oracle. Rochester: Inner Traditions / Bear & Company. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-89281-093-2.

- Wagner 2005, p. 49

- Wagner 2005, p. 55

- Wagner 2005, pp. 44–45

- Wagner 2005, p. 59

- McLeod & Mees 2006, pp. 106–107

- Rhys Mountfort, Paul (2003). Nordic Runes: Understanding, Casting, and Interpreting the Ancient Viking Oracle. Rochester: Inner Traditions / Bear & Company. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-89281-093-2.

- Boyer 1991, pp. 74–75

- Boyer 1991, pp. 172–173

- Andrea Heusler, « Die Geschichte vom Völsi; Eine altnordische Bekehrungsanekdote » (in German), ZfVk, 1903, p. 24-39

- Wagner 2005, p. 43

- Boyer 1987, chap 13 ; chap 18 ; chap 58-59

- Wagner 2005, p. 51

- Boyer 1987, p. 1925

- Boyer 1987, pp. 1296–1297

- Eric Oxenstierna, Les Vikings, histoire et civilisation (in French). Paris, 1962, p. 194

- W. Grönbech, Kultur und Religion der Germanen, vol. 2, Darmstadt, (in German) 1991, p. 189-190

- Académie royale de médecine de Belgique (1847). Bulletin de l'Académie royale de médecine de Belgique (in French). Vol. 6. De Mortier. p. 603, 604. ISSN 0377-8231.

- & Boyer 1979, pp. 381–382

- Fédération des sociétés d'histoire et d'archéologie d'Alsace (1851). Revue d'Alsace (in French). Vol. 111. Fédération des sociétés d'histoire et d'archéologie d'Alsace. p. 554.

- R. Hindringer, Weiheross und Rossweihe, Munich (in German), 1932, pl. 3, ill. 3

- Bertrand Hell, « Éléments du bestiaire populaire alsacien » dans Revue des sciences sociales de la France de l'Est (in French), n° 12 et 12 bis, 1983, p. 209

- Wagner 2005, pp. 45–46

- Olaus Magnus, Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus (in Latin), XV, 8 et 9, cited by Wagner 2005, p. 47

- Grimm & Meyer 1968, p. 1041

- Franz Lipp, « Pferdeschätel- und andere Tieropfer im Mondseeland » (in German) in Mitteilungen der Anthropolischen Gesellschaft in Wien 95, 1965, p. 296-305

- Kolbe, Hessische Volkssitten und Gebräuche im Lichte der heidnischen Vorzeit, (in German) 1888, p. 105

- Wagner 2005, p. 57

- Grimm & Meyer 1968, p. 550

- R. Wolfram, « Die gekreuzten Pferdeköpfe als Giebelzeichenn », Veröffentlichungen des instituts für Volkskunde an der Universität Wien 3, (in German) Vienna, 1968, p. 78, 84, 85

- Grimm 1883, p. 844

- Simek 1993, p. 294

- Nicolaus Gryse, Spegel des Antichristlichen Pawestdoms vnd Lutterischen Christendoms, S. Müllman, Rostock, cited by Karl Meisen, Die sagen vom Wûtenden Heer und Wilden Jäger. Münster (in German) in Westphalie, 1935, p. 121

- James George Frazer, Le Rameau d'or, vol. III, chap VIII, p. 192-193

- Burns 2005, pp. 105–106

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Boyer, Régis (2002). L'Edda poétique. L'Espace intérieur (in French). Paris: Fayard.

- Boyer, Régis (1987). Sagas islandaises. Bibliothèque de la Pléiade (in French). Gallimard. ISBN 978-2-07-011117-6.

- Larrington, Carolyne (1999). Poetic Edda. Oxford University Press.

- Dillmann, François-Xavier [in French] (2003), Notes from : Snorri Sturluson, L'Edda : Récits de mythologie nordique

- Faulkes, Anthony (1995). Edda. Londres: Everyman. ISBN 978-0-460-87616-2.

Academic publications

- Boyer, Régis (1979). La vie religieuse en Islande (1116-1264): D'après la Sturlunga Saga et les Sagas des Evêques (in French). Paris: Fondation Singer-Polignac.

- Boyer, Régis (1991). Yggdrasill: la religion des anciens Scandinaves. Bibliothèque historique (in French). Paris: Payot. ISBN 978-2-228-88469-3.

- Boyer, Régis (1997). "Cheval". Héros et Dieux du Nord: Guide iconographique. Tout l’Art. Flammarion. p. 32-33. ISBN 2-08-012274-6.

- Burns, Marjorie (2005). Perilous Realms: Celtic and Norse in Tolkien's Middle-earth. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-3806-7.

- Jennbert, Kristina (2011). Animals and Humans: Recurrent Symbiosis in Archaeology and Old Norse Religion. Vol. 14 de Vägar till Midgård. Nordic Academic Press. ISBN 978-91-85509-37-9.

- Lindow, John (2002). Norse Mythology : A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs.

- Wagner, Marc-André (2005). Le cheval dans les croyances germaniques: paganisme, christianisme et traditions. Vol. 73 de Nouvelle bibliothèque du moyen âge. Paris: Honoré Champion. ISBN 978-2-7453-1216-7.

Additional

- Grimm, Jacob; Meyer, Elard Hugo (1968). Deutsche Mythologie (in German). Graz, Akademische Druck-u. Verlagsanstalt. OCLC 1998774.

- Grimm, Jacob (1883). Teutonic Mythology: traduction de la quatrième édition par James Steven Stallybrass. Vol. 2. Londres: George Bell and Sons.

- Farrar, Janet; Russell, Virginia (1992). The magical history of the horse. Londres: Robert Hale. ISBN 978-0-7090-4366-9.

- Hausman, Loretta (2003). The Mythology of Horses: Horse Legend and Lore Throughout the Ages. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-609-80846-7.

- Jung, Carl Gustav (1993). Métamorphose de l'âme et ses symboles (in French). Paris: Georg. ISBN 978-2-253-90438-0.

- McLeod, Mindy; Mees, Bernard (2006). Runic Amulets and Magic Objects. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-205-8.

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Londres: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-34520-5.

- Simek, Rudolf (1993). Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Translated by Angela Hall. Suffolk: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-513-7. (Reissued in 2007 : Simek, Rudolf (2007). Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Translated by Angela Hall. D.S. Brewer.

- Marc-André Wagner (2006). Dictionnaire mythologique et historique du cheval. Cheval chevaux. Monaco: Éditions du Rocher. ISBN 978-2-268-05996-9.

Articles and conferences

- Loumand, Ulla (2006). "The Horse and its Role in Icelandic Burial Practices, Mythology, and Society". In Nordic Academic Press (ed.). Old Norse Religion in Long Term Perspectives: Origins, Changes and Interactions, an International Conference in Lund, Sweden, June 3-7, 2004. Vol. 8. Lund. ISBN 978-91-89116-81-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gjessing, Gutorm (1943). "Hesten i forhistorisk kunst og kultus". Viking (in Norwegian) (7): 5–143.