The Entombment of Christ (Caravaggio)

Caravaggio created one of his most admired altarpieces, The Entombment of Christ, in 1603–1604 for the second chapel on the right in Santa Maria in Vallicella (the Chiesa Nuova), a church built for the Oratory of Saint Philip Neri.[1] A copy of the painting is now in the chapel, and the original is in the Vatican Pinacoteca. The painting has been copied by artists as diverse as Rubens,[2] Fragonard, Géricault and Cézanne.[1]

| The Entombment of Christ | |

|---|---|

| Italian: Deposizione | |

.jpg.webp) | |

| Artist | Caravaggio |

| Year | 1603–1604 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 300 cm × 203 cm (120 in × 80 in) |

| Location | Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City |

History

On 11 July 1575, Pope Gregory XIII (1572-1585) issued a bull confirming the formation of a new society called the Oratory and granting it the church of Santa Maria in Vallicella. Two months after the bull, the rebuilding of the church commenced. Envisaged in the planned reconstruction of the Chiesa Nuova (new church), as it became known, was the dedication of all the altars to the mysteries of the Virgin. Starting in the left transept and continuing around the five chapels on either side of the nave to the right transept, the altars are dedicated to the Presentation of the Temple, the Annunciation, the Visitation, the Nativity, the Adoration of the Shepherds, the Circumcision, the Crucifixion, the Pietà, the Resurrection, the Ascension, the Descent of the Holy Ghost, the Assumption and the Coronation.[3]

The Entombment was probably planned and begun in 1602/3.[1] The chapel in which the Entombment was to be hung, was dedicated to the Pietà, and was founded by Pietro Vittrice, a friend of Pope Gregory XIII and close follower of Filippo Neri.[4] The Capella della Pietà occupied a 'privileged' position in the Chiesa Nuova: Mass could be celebrated from it and it was granted special indulgences.[3]

The chapel, placed in the right nave of the Chiesa Nuova, was conceded to Vittrice in June 1577, and the foundation of the chapel ratified in September 1580. Some time after his death in March 1600, a legacy of 1,000 scudi became available for the maintenance of the chapel, and it was built in 1602, which is then held to be the earliest date for the commission of Caravaggio's painting.[5] Indeed, on 1 September 1604, it is described as 'new' in a document recording that it had been paid for by Girolamo Vittrice, Pietro's nephew and heir.[1][6]

Girolamo Vittrice had a direct connection with Caravaggio: in August 1586 he married Orinzia di Lucio Orsi, the sister of Caravaggio's friend Prospero Orsi and the niece of the humanist Aurelio Orsi. Aurelio, in turn, was a one-time mentor to the young Maffeo Barberini, who became Pope Urban VIII in 1623. It is through these connections that Girolamo's son, Alessandro, became bishop of Alatri in 1632, and was able to bestow the gift of Caravaggio's Fortune Teller (now in the Louvre) on Pope Innocent X Pamphilij after being appointed governor of Rome in 1647.[5]

The painting was universally admired and written about by such critics as Giulio Mancini,[lower-alpha 1] Giovanni Baglione (1642),[8][lower-alpha 2] Gian Pietro Bellori (1672)[9][lower-alpha 3] and Francesco Scanelli (1657).[11][lower-alpha 4]

The painting was taken to Paris in 1797 for the Musée Napoléon, returned to Rome and installed in the Vatican in 1816.[5][7][lower-alpha 5]

Composition

This counter-reformation painting – with a diagonal cascade of mourners and cadaver-bearers descending to the limp, dead Christ and the bare stone – is not a moment of transfiguration, but of mourning. As the viewer's eye descends from the gloom there is, too, a descent from the hysteria of Mary of Clopas through subdued emotion to death as the final emotional silencing. Unlike the gory post-crucifixion Jesus in morbid Spanish displays, Italian Christs die generally bloodlessly, and slump in a geometrically challenging display. As if emphasizing the dead Christ's inability to feel pain, a hand enters the wound at his side. His body is one of a muscled, veined, thick-limbed laborer rather than the usual, bony-thin depiction.

Two men carry the body. John the Evangelist, identified only by his youthful appearance and red cloak supports the dead Christ on his right knee and with his right arm, inadvertently opening the wound. Nicodemus (with the face of Michelangelo) grasps the knees in his arms, with his feet planted at the edge of the slab. Caravaggio balances the stable, dignified position of the body and the unstable exertions of the bearers.[12]

While faces are important in painting generally, in Caravaggio it is important always to note where the arms are pointing. Skyward in The Conversion of Saint Paul on the Road to Damascus, towards Levi in The Calling of Saint Matthew. Here, the dead God's fallen arm and immaculate shroud touch stone; the grieving Mary of Cleophas gesticulates to Heaven. In some ways, that was the message of Christ: God come to earth, and mankind reconciled with the heavens. As usual, even with his works of highest devotion, Caravaggio never fails to ground himself. In the center is Mary Magdalene, drying her tears with a white handkerchief, face shadowed. Tradition held that the Virgin Mary be depicted as eternally young, but here Caravaggio paints the Virgin as an old woman. The figure of the Virgin Mary is also partially obscured behind John; we see her in the robes of a nun and her arms are held out to her side, imitating the line of the stone they stand upon. Her right hand hovers above his head as if she is reaching out to touch him. Seen together, the three women constitute different, complementary expressions of suffering.[13]

The left figure imitates the costume from Caravaggio's Penitent Magdalene (Doria Pamphilj Gallery, Rome); the right figure reminds us of his Mary in Conversion of the Magdalene (Detroit Institute of Art).[12] Andrew Graham-Dixon asserts that these figures were modelled by Fillide Melandroni, a frequent model in his works and about 22 years old at the time.[6]

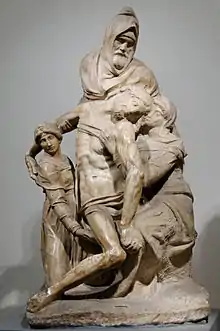

Caravaggio's composition also seems to be related to Michelangelo's Pietà as St. Peters (especially in the figure of the Madonna),[1] and his Florentine Pietà (Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence), from which he takes the figure of Nicodemus. In the latter case, Caravaggio transports Michelangelo's self-portrait to his own painting.[14]

Although Caravaggio's Entombment of Christ is related to Michelangelo's Pieta, it is not a Pieta because even if there is the presence of the Virgin Mary in the painting there are not the right number nor types of people present.[15]

Caravaggio also sets up a comparison with Raphael by using as a source for the main group, that of Raphael's Borghese Deposition. This comparison contrasts High Renaissance idealism with Caravaggio's own naturalism.

Caravaggio's Entombment of Christ is not a Burial because the body of Christ is not being lowered on to a tomb but instead being laid on a stone slab.[15]

Interpretations

Caravaggio's painting is a visual counterpart to the Mass, with the priest raising the newly consecrated host with the Entombment as a backdrop. The privileged placement of the altar would have meant that this was a daily occurrence; the act perfectly juxtaposing the body in the picture with the host as the priest intones "This is my very body." Jacopo Pontormo's Deposition (ca. 1525–1528) in Florence performs a similar function, similarly displayed over an altar. Such pictures are presentations of the Corpus Domini rather than enactments of the deposition of entombment of Christ.[1]

Starting in the 17th-century, Caravaggio's picture has been considered a scene of active burial. This interpretation was based on heroic formula derived from antique sources, that of Adonis or Meleager: head thrown back and one arm hanging limply by the side. Indeed, Raphael's Borghese Deposition is an example of this formula. The placing of Christ's body on a flat stone also had precedents in painting, notably Rogier van der Weyden's Lamentation in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence.[3]

On closer inspection, Caravaggio painting does not fit this formula, since these ancient types are transportation scenes, whereas his, as in Van der Weyden's case, is decidedly not. Instead the composition assumes the traditional pyramidal shape of a traditional Pietà type. Given the interpretation of the picture as a Pietà type, the flat stone (previously interpreted as a lid or door to a tomb) can be reinterpreted as a reference to the Stone of Unction, today enshrined in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem. This stone was used to place Christ's body when it was anointed and wound in linen clothes, as related in the Gospel of John.[3]

Seldom noticed by modern viewers is Caravaggio's insertion of the plant in the lower left of the Entombment. Commonly called mullein, Verbascum thapsus was thought to have medicinal properties and was said to ward off evil spirits. It was associated with the iconography of Saint John the Baptist.[16] Caravaggio also uses it in his Saint John the Baptist and Rest on the Flight into Egypt.[17]

Derivative works

Peter Paul Rubens, The Entombment (1611/12), National Gallery of Canada

Peter Paul Rubens, The Entombment (1611/12), National Gallery of Canada Dirck van Baburen, Lamentation (1617-1621), copy after original in Church of San Pietro in Montorio, Rome

Dirck van Baburen, Lamentation (1617-1621), copy after original in Church of San Pietro in Montorio, Rome Guy François, The Entombment of Christ, Ashmolean Museum

Guy François, The Entombment of Christ, Ashmolean Museum Pietro Fontana after Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Entombment of Christ, 1835/1910, engraving, Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC

Pietro Fontana after Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Entombment of Christ, 1835/1910, engraving, Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC

See also

Notes

- "The Cristo Deposto is in the Chiesa Nuova." Trattato..., 59v[7]

- "In the Chiesa Nuova, in the second chapel to the right, is the Cristo Morto about to be buried and some other figures, all done in oil; they say that it is his best work."[7]

- "Truly among the best works to issue from Michele's brush, the Deposition of Christ in the Chiesa Nuova of the Fathers of the Oratory is deservedly held in esteem; the figures are situated on a slab at the opening of the sepulcher. The sacred body appears in the middle, Nicodemus supports it at the feet with his arms under the knees, and as the thighs are lowered, the legs protrude. Caravaggio has used Michelangelo's face for the face of Nicodemus. On the far side, Saint John places an arm under the shoulder of the Redeemer, whose face and deathly pale breast remain upturned, while his arm hangs down with the sheet; and all the nudity is portrayed with the power of the most accurate imitation. Behind Nicodemus the grieving Marys are partially visible, one with upraised arms, another with her veil to her eyes, and the third gazing at the Lord."[10]

- "Of extraordinary excellence is the dead Christ being carried to burial, in the Chiesa Nuova."[7]

- The painting currently hanging in the Chiesa Nuova is a copy by Michelle Koeck.[5]

References

- Hibbard, Howard (1985). Caravaggio. Oxford: Westview Press. pp. 171–179. ISBN 9780064301282.

- Glen, Thomas (1988). "Rubens after Caravaggio: The "Entombment"". RACAR: Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review. 15 (1): 19–22. doi:10.7202/1073430ar. JSTOR 42630378.

- Graeve, Mary Ann (September 1958). "The Stone of Unction in Caravaggio's Painting for the Chiesa Nuova". The Art Bulletin. 40 (3): 223–238. doi:10.2307/3047779. JSTOR 3047779.

- Langdon, Helen (2000). Caravaggio: A Life. Westview Press. ISBN 9780813337944.

- Sickel, Lothar (July 2001). "Remarks on the Patronage of Caravaggio's 'Entombment of Christ'". The Burlington Magazine. 143 (1180): 426–429. JSTOR 889098.

- Graham-Dixon, Andrew (2011). Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 9780241954645.

- Friedländer, Walter (1974). Caravaggio Studies. Princeton and London: Princeton University Press. pp. 186–189. ISBN 0691003084.

- Baglione, Giovanni (1642). Le Vite De' Pittori, Scultori Et Architetti (in Italian). Rome: Nella stamperia d'Andrea Fei. p. 137.

- Bellori, Giovanni Pietro (1672). Vite de'Pittori, Scultori et Architetti Moderni, Parte Prima. Rome: Mascardi. p. 207.

- Bellori, Giovanni Pietro; Wohl, Alice Sedgwick; Wohl, Hellmut; Montanari, Tomaso (2005). Giovan Pietro Bellori: The Lives of the Modern Painters, Sculptors and Architects: A New Translation and Critical Edition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521781879. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- Scannelli, Francesco (1657). Il microcosmo della pittura (in Italian). Peril Neri. p. 199.

- Wright, Georgia (March 1978). "Caravaggio's Entombment Considered in Situ". The Art Bulletin. 60 (1): 35–42. doi:10.2307/3049742. JSTOR 3049742.

- The Museo del Prado. The Entombment of Christ, Caravaggio. n.d. 3 July 2015. <https://www.museodelprado.es/en/exhibitions/exhibitions/at-the-museum/la-obra-invitada-emel-descendimientoem-caravaggio/la-obra/>

- Wolfgang Stechow (1964). "Joseph of Arimathea or Nicodemus". In Lotz, Wolfgang; Moeller, Lise Lotte (eds.). Studien zur toskanischen Kunst : Festschrift für Ludwig Heinrich Heydenreich. Munich. pp. 289–302.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bertoldi, Susanna (2011). The Vatican Museums, Discover the history, the works of art, the collections. Vatican City: Sillabe. p. 272. ISBN 978-88-8271-210-5.

- White, Eric Marshall (Winter 1996). "Albrecht Altdorfer's botanical attribute for Saint John the Baptist". Notes in the History of Art. 15 (2): 15–21. doi:10.1086/sou.15.2.23205516. JSTOR 23205516. S2CID 191366409.

- Witting, Felix; Patrizi, M.L. (2012). Michelangelo da Caravaggio. New York: Parkstone International. p. 90. ISBN 9781780427270.

External links

Media related to Entombment of Christ by Caravaggio at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Entombment of Christ by Caravaggio at Wikimedia Commons