The Battle of Maldon

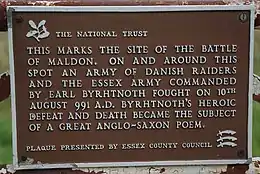

"The Battle of Maldon" is the name given to an Old English poem of uncertain date celebrating the real Battle of Maldon of 991, at which an Anglo-Saxon army failed to repulse a Viking raid. Only 325 lines of the poem are extant; both the beginning and the ending are lost.

The poem

The poem is told entirely from the perspective of the Anglo-Saxons, and names many individuals that Mitchell and Robinson[1] believe were real Englishmen.

Mitchell and Robinson conjecture that the lost opening of the poem must have related how Byrhtnoth, an Anglo-Saxon ealdorman, hearing of the Viking raid, raised his troops and led them to the shore.[1]

The poem as we have it begins with the Anglo-Saxon warriors dismounting to prepare for battle. A Viking force is encamped on an island that can be reached by a causeway. A Viking messenger offers Byrhtnoth peace if he will consent to pay tribute. Byrhtnoth angrily refuses, telling the messenger that he will fight the heathen Vikings in defence of his land, and the land of his king, Æthelred. In his "ofermōde"*, Byrhtnoth allows the Vikings to cross to the mainland, giving them room in which to do battle, rather than keeping them penned in on the island.

Individual episodes from the ensuing carnage are described, and the fates of several Anglo-Saxon warriors depicted – notably that of Byrhtnoth himself, who dies urging his soldiers forward and commending his soul to God. Not all the English are portrayed as heroic however: one, Godric the son of Odda (there are two Godrics in the poem), flees the battle with his brothers and, most improperly, does so on Byrhtnoth's horse. Several lines later, the English lord Offa claims that the sight of Byrhtnoth's horse (easily recognisable from its trappings) fleeing, and so Byrhtnoth, as it would appear from a distance, has bred panic in the ranks and left the English army in danger of defeat. There follow several passages in which English warriors voice their defiance and their determination to die with their lord, and descriptions of how they are then killed by the un-personified "sea-wanderers". The poem as it has come down to us ends with another Godric disappearing from view. This time, it is Godric, the son of Æthelgar, advancing into a body of Vikings and being killed.

- "ofermōde," occurring in line 89, has caused much discussion. Literally "high spirits" or "overconfidence", "ofermōde" is usually translated as "pride", and occurs in Anglo-Saxon Genesis poems when referring to Lucifer. Both Glenn and Alexander translate it as "arrogance"[2] and Bradley as "extravagant spirit".[3]

History of the text

In 1731, the only known manuscript of the poem (which, as with the modern version, was missing its beginning and ending[3]) was destroyed in the fire at Ashburnham House that also damaged and destroyed several other works in the Cotton library. The poem has come down to us thanks to the transcription of it made c. 1724, which was published by Thomas Hearne in 1726. After being lost, the original transcription was found in the Bodleian Library in the 1930s.[4][5] Who made this original transcription is still unclear; some favour John Elphinstone,[2][3][4][5] and others David Casley.[1][6]

Date of composition

According to some scholars, the poem must have been written close to the events that it depicts, given the historical concreteness and specificity of the events depicted in the poem.[7] According to Irving, the specific events told with such clarity could only have been composed shortly after the events had taken place, and before legend had been introduced into the poem.[7] While this may seem strange to a modern audience, who are used to “realistic fiction,” this is in fact a fairly strong argument for an early composition date. The lack of legendary elements seems to indicate that this poem was written at a time when witnesses or close descendants of witnesses would have been able to attest to the validity and accuracy of the facts.

John D. Niles, in his essay “Maldon and Mythopoesis”, also argues for an early composition date. He states that the three direct references to Æthelred the Unready necessitate an early composition date, before Æthelred had achieved his reputation for ineffectiveness.[8] This argument hinges upon Byrhtnoth's, and the poet's, degree of knowledge of Aethelred's ill reputation. If Byrhtnoth had known of Aethelred's nature, would he have been willing to sacrifice himself for an undeserving king, effectively throwing away his own life and those of his men? Niles indicates that this does not appear to be supportable through the actions and statements of Byrhtnoth throughout the poem.[8] Apparently Byrhtnoth did not know of the king's nature, and most likely the poet himself did not know of the king's nature either. If the poet had known, he would likely have mentioned it in an aside, similar to the way he treats the coward Godric when he is first introduced within the poem.

Some of these arguments have been rebutted; George Clark, for instance, argues against an early composition date, rebutting Irving, and states that the detail and specificity found in the poem do not necessarily necessitate an early composition date.[9] Clark argues that if one accepts the detail and specificity as indicators that the events were related to the poet by a witness or close descendant, then the presenter or narrator must have either been “one of the cowards or a retainer who missed the battle by legitimate accident and later chatted with one or more of the men who abandoned his lord”.[9]

Other arguments against an early date focus on vocabulary and spelling, which, it is argued, suggest that the poem had its origins in the 11th century in western England, rather than from the 10th century in eastern England (where Maldon is located).[9][10] These arguments are not based upon one or two spellings which may have been transcribed poorly, but rather upon the uniform spelling of specific indicative words in Old English which are often associated with dialectical writing, such as “sunu” and “swurd”.[10] Clark further argues against an early composition date by exposing the contradictory descriptions of Byrhtnoth, both within the poem and against historical record. According to Clark, the poet of Maldon describes Byrhtnoth as an old warrior, but able-bodied (paraphrased); however, later in the poem Byrhtnoth is disarmed easily by a Viking. Clark argues that these two events are conflicting and therefore demonstrate the lack of historical accuracy within the poem.[9] Clark also argues that the poet never mentions the great height of Byrhtnoth, nor does he mention Byrhtnoth “enfeebled by age”,[9] which indicates that the poet was removed from the event, for the historical records show that Byrhtnoth was tall, which the poet would not have left out due to its indicative nature.[9]

Scholarship

George K. Anderson dated "The Battle of Maldon" to the 10th century and felt that it was unlikely that much was missing.[11] R. K. Gordon is not so specific, writing that this "last great poem before the Norman Conquest ... was apparently written very soon after the battle",[12] while Michael J. Alexander speculates that the poet may even have fought at Maldon.[2]

S. A. J. Bradley reads the poem as a celebration of pure heroism – nothing was gained by the battle, rather the reverse: not only did Byrhtnoth, "so distinguished a servant of the Crown and protector and benefactor of the Church," die alongside many of his men in the defeat, but the Danegeld was paid shortly after – and sees in it an assertion of national spirit and unity, and in the contrasting acts of the two Godrics the heart of the Anglo-Saxon heroic ethos.[3] Mitchell and Robinson are more succinct: "The poem is about how men bear up when things go wrong".[1] Several critics have commented on the poem's preservation of a centuries-old Germanic ideal of heroism:

Maldon is remarkable (apart from the fact that it is a masterpiece) in that it shows that the strongest motive in a Germanic society, still, nine hundred years after Tacitus, was an absolute and overriding loyalty to one's lord.

— Michael J. Alexander, The Earliest English Poems

Modern sequel

The Anglo-Saxon scholar and writer J. R. R. Tolkien was inspired by the poem to write The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm's Son, an alliterative dialogue between two characters at the end of the battle. In publishing the work, Tolkien included alongside it an essay on the original poem and another on the word "ofermōde".

In 1959, author Pauline Clarke wrote Torolv the Fatherless, a children's novel set in the Anglo-Saxon era. The novel focuses on a lost Viking child, Torolv, who is adopted by the Anglo-Saxon court, and eventually witnesses the Battle of Maldon, in which the child's father may be one of the attacking Vikings. Clarke ends the novel with her own Modern English translation of the Anglo-Saxon poem The Battle of Maldon. In the early 1940s, Clarke had been an undergraduate at Oxford University, and attended lectures by Tolkien.

See also

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle – records the battle and the paying of the Danegeld.

- Liber Eliensis – or the Book of Ely; features another retelling of the battle.

- Sermo Lupi ad Anglos – or The Sermon of the Wolf to the English; in which this and other Viking raids are seen as punishment for England's lax morals.

- Byrhtferth – whose Life of Oswald also features the battle and the death of Byrhtnoth.

Notes

- A Guide to Old English, 5th ed. by Bruce Mitchell and Fred C. Robinson, Blackwell, 1999 reprint ISBN 978-0-631-16657-3

- The Earliest English Poems translated by Michael J. Alexander, Penguin Books, 1966

- Anglo-Saxon Poetry translated and edited by S. A. J. Bradley, Everyman's Library, 2000 reprint ISBN 978-0-460-87507-3

- The poem translated into modern English by Jonathan A. Glenn Archived 2009-09-30 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 27 October 2009

- Commentary Retrieved on 27 October 2009

- The Battle of Maldon: Fiction and Fact, edited by Janet Cooper, Hambledon , 1993 ISBN 978-1-85285-065-4

- The Heroic Style in "The Battle of Maldon". Author(s): Edward B. Irving, Jr. Source: Studies in Philology, Vol. 58, No. 3 (July , 1961), pp. 457–67. Published by: University of North Carolina Press. JSTOR 4173350

- "Maldon and Mythopoesis" by John D. Niles, in Old English Poetry (2002), ed. by Roy Liuzza, pp. 445–74.

- The Battle of Maldon: A Heroic Poem. Author(s): George Clark. Source: Speculum, Vol. 43, No. 1 (January , 1968), pp. 52–71. Published by: Medieval Academy of America. JSTOR 2854798

- The Cambridge Old English Reader (2004). Richard Marsden. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

- Old and Middle English Literature From the Beginnings to 1485 by George K. Anderson, OUP, 1950, pp. 29–30

- Anglo-Saxon Poetry selected and translated by R. K. Gordon, J.M. Dent & Sons, London, pp. vii, 361

Further reading

- Atherton, Mark (2021). The Battle of Maldon: War and Peace in Tenth-Century England. London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781350167506. (on the poem, not the battle)

- Neidorf, Leonard. "II Æthelred and the Politics of The Battle of Maldon." Journal of English and Germanic Philology 111 (2012): 451–73.

- Robinson, Fred C. "Some Aspects of the Maldon Poet's Artistry." Journal of English and Germanic Philology 75 (1976): 25–40 JSTOR 27707983

- Scragg, Donald. The Return of the Vikings: The Battle of Maldon 991. Tempus Publishing, 2006, ISBN 978-0-7524-2833-8.

External links

- "The Battle of Maldon" is edited, annotated and linked to digital images of its manuscript transcription and original printing, with modern translation, in the Old English Poetry in Facsimile Project: https://oepoetryfacsimile.org/

- The Battle of Maldon Online modern English translation

- Hypertext version of the poem with translations and commentary

- The poem in original Anglo-Saxon

- The poem in original Anglo-Saxon

- Read aloud in Anglo-Saxon

- The poem translated into modern English by Jonathan A. Glenn

- Translated by James M. Garnett at Project Gutenberg

- The poem translated into modern English by Wilfrid Berridge

- Bartleby Essay from The Cambridge History of English and American Literature

- Review of an edition and translation of the text