The Art of Computer Programming

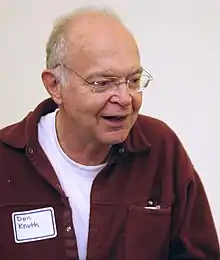

The Art of Computer Programming (TAOCP) is a comprehensive monograph written by the computer scientist Donald Knuth presenting programming algorithms and their analysis. Volumes 1–5 are intended to represent the central core of computer programming for sequential machines.

The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1: Fundamental Algorithms | |

| Author | Donald Knuth |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Non-fiction Monograph |

| Publisher | Addison-Wesley |

Publication date | 1968– (the book is still incomplete) |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover) |

| ISBN | 0-201-03801-3 |

| 519 | |

| LC Class | QA76.75 |

When Knuth began the project in 1962, he originally conceived of it as a single book with twelve chapters. The first three volumes of what was then expected to be a seven-volume set were published in 1968, 1969, and 1973. Work began in earnest on Volume 4 in 1973, but was suspended in 1977 for work on typesetting prompted by the second edition of Volume 2. Writing of the final copy of Volume 4A began in longhand in 2001, and the first online pre-fascicle, 2A, appeared later in 2001.[1] The first published installment of Volume 4 appeared in paperback as Fascicle 2 in 2005. The hardback Volume 4A, combining Volume 4, Fascicles 0–4, was published in 2011. Volume 4, Fascicle 6 ("Satisfiability") was released in December 2015; Volume 4, Fascicle 5 ("Mathematical Preliminaries Redux; Backtracking; Dancing Links") was released in November 2019.

Volume 4B consists of material evolved from Fascicles 5 and 6.[2] The manuscript was sent to the publisher on August 1, 2022, and the volume was published in September 2022.[3] Fascicle 7, planned for Volume 4C, was the subject of Knuth's talk on August 3, 2022.[4]

History

After winning a Westinghouse Talent Search scholarship, Knuth enrolled at the Case Institute of Technology (now Case Western Reserve University), where his performance was so outstanding that the faculty voted to award him a master of science upon his completion of the bachelor's degree. During his summer vacations, Knuth was hired by the Burroughs Corporation to write compilers, earning more in his summer months than full professors did for an entire year.[5] Such exploits made Knuth a topic of discussion among the mathematics department, which included Richard S. Varga.

In January 1962, when he was a graduate student in the mathematics department at Caltech, Knuth was approached by Addison-Wesley to write a book about compiler design, and he proposed a larger scope. He came up with a list of twelve chapter titles the same day. In the summer of 1962 he worked on a FORTRAN compiler for UNIVAC. During this time, he also came up with a mathematical analysis of linear probing, which convinced him to present the material with a quantitative approach. After receiving his Ph.D. in June 1963, he began working on his manuscript, of which he finished his first draft in June 1965, at 3000 hand-written pages.[6] He had assumed that about five hand-written pages would translate into one printed page, but his publisher said instead that about 1+1⁄2 hand-written pages translated to one printed page. This meant he had approximately 2000 printed pages of material, which closely matches the size of the first three published volumes. At this point, Knuth received support from Richard S. Varga, who was the scientific adviser to the publisher. Varga was visiting Olga Taussky-Todd and John Todd at Caltech. With Varga's enthusiastic endorsement, the publisher accepted Knuth's expanded plans. In its expanded version, the book would be published in seven volumes, each with just one or two chapters.[7] Due to the growth in Chapter 7, which was fewer than 100 pages of the 1965 manuscript, per Vol. 4A p. vi, the plan for Volume 4 has since expanded to include Volumes 4A, 4B, 4C, 4D, and possibly more.

In 1976, Knuth prepared a second edition of Volume 2, requiring it to be typeset again, but the style of type used in the first edition (called hot type) was no longer available. In 1977, he decided to spend some time creating something more suitable. Eight years later, he returned with TEX, which is currently used for all volumes.

The offer of a so-called Knuth reward check worth "one hexadecimal dollar" (100HEX base 16 cents, in decimal, is $2.56) for any errors found, and the correction of these errors in subsequent printings, has contributed to the highly polished and still-authoritative nature of the work, long after its first publication. Another characteristic of the volumes is the variation in the difficulty of the exercises. Knuth even has a numerical difficulty scale for rating those exercises, varying from 0 to 50, where 0 is trivial, and 50 is an open question in contemporary research.[8]

Knuth's dedication reads:

This series of books is affectionately dedicated

to the Type 650 computer once installed at

Case Institute of Technology,

with whom I have spent many pleasant evenings.[lower-alpha 1]

Assembly language in the book

All examples in the books use a language called "MIX assembly language", which runs on the hypothetical MIX computer. Currently, the MIX computer is being replaced by the MMIX computer, which is a RISC version. Software such as GNU MDK[9] exists to provide emulation of the MIX architecture. Knuth considers the use of assembly language necessary for the speed and memory usage of algorithms to be judged.

Critical response

Knuth was awarded the 1974 Turing Award "for his major contributions to the analysis of algorithms […], and in particular for his contributions to the 'art of computer programming' through his well-known books in a continuous series by this title."[10] American Scientist has included this work among "100 or so Books that shaped a Century of Science", referring to the twentieth century,[11]and within the computer science community it is regarded as the first and still the best comprehensive treatment of its subject. Covers of the third edition of Volume 1 quote Bill Gates as saying, "If you think you're a really good programmer… read (Knuth's) Art of Computer Programming… You should definitely send me a résumé if you can read the whole thing."[12] The New York Times referred to it as "the profession's defining treatise".[13]

Volumes

Completed

- Volume 1 – Fundamental Algorithms

- Chapter 1 – Basic concepts

- Chapter 2 – Information structures

- Volume 2 – Seminumerical Algorithms

- Chapter 3 – Random numbers

- Chapter 4 – Arithmetic

- Volume 3 – Sorting and Searching

- Volume 4A – Combinatorial Algorithms

- Chapter 7 – Combinatorial searching (part 1)

- Volume 4B – Combinatorial Algorithms

- Chapter 7 – Combinatorial searching (part 2)

Planned

- Volume 4C, 4D, ... Combinatorial Algorithms (chapters 7 & 8 released in several subvolumes)

- Chapter 7 – Combinatorial searching (continued)

- Chapter 8 – Recursion

- Volume 5 – Syntactic Algorithms

- Chapter 9 – Lexical scanning (also includes string search and data compression)

- Chapter 10 – Parsing techniques

- Volume 6 – The Theory of Context-Free Languages

- Volume 7 – Compiler Techniques

Chapter outlines

Volume 1 – Fundamental Algorithms

- Chapter 1 – Basic concepts

- 1.1. Algorithms

- 1.2. Mathematical Preliminaries

- 1.2.1. Mathematical Induction

- 1.2.2. Numbers, Powers, and Logarithms

- 1.2.3. Sums and Products

- 1.2.4. Integer Functions and Elementary Number Theory

- 1.2.5. Permutations and Factorials

- 1.2.6. Binomial Coefficients

- 1.2.7. Harmonic Numbers

- 1.2.8. Fibonacci Numbers

- 1.2.9. Generating Functions

- 1.2.10. Analysis of an Algorithm

- 1.2.11. Asymptotic Representations

- 1.2.11.1. The O-notation

- 1.2.11.2. Euler's summation formula

- 1.2.11.3. Some asymptotic calculations

- 1.3 MMIX (MIX in the hardback copy but updated by fascicle 1)

- 1.3.1. Description of MMIX

- 1.3.2. The MMIX Assembly Language

- 1.3.3. Applications to Permutations

- 1.4. Some Fundamental Programming Techniques

- 1.4.1. Subroutines

- 1.4.2. Coroutines

- 1.4.3. Interpretive Routines

- 1.4.3.1. A MIX simulator

- 1.4.3.2. Trace routines

- 1.4.4. Input and Output

- 1.4.5. History and Bibliography

- Chapter 2 – Information Structures

- 2.1. Introduction

- 2.2. Linear Lists

- 2.2.1. Stacks, Queues, and Deques

- 2.2.2. Sequential Allocation

- 2.2.3. Linked Allocation (topological sorting)

- 2.2.4. Circular Lists

- 2.2.5. Doubly Linked Lists

- 2.2.6. Arrays and Orthogonal Lists

- 2.3. Trees

- 2.3.1. Traversing Binary Trees

- 2.3.2. Binary Tree Representation of Trees

- 2.3.3. Other Representations of Trees

- 2.3.4. Basic Mathematical Properties of Trees

- 2.3.4.1. Free trees

- 2.3.4.2. Oriented trees

- 2.3.4.3. The "infinity lemma"

- 2.3.4.4. Enumeration of trees

- 2.3.4.5. Path length

- 2.3.4.6. History and bibliography

- 2.3.5. Lists and Garbage Collection

- 2.4. Multilinked Structures

- 2.5. Dynamic Storage Allocation

- 2.6. History and Bibliography

Volume 2 – Seminumerical Algorithms

- Chapter 3 – Random Numbers

- 3.1. Introduction

- 3.2. Generating Uniform Random Numbers

- 3.2.1. The Linear Congruential Method

- 3.2.1.1. Choice of modulus

- 3.2.1.2. Choice of multiplier

- 3.2.1.3. Potency

- 3.2.2. Other Methods

- 3.2.1. The Linear Congruential Method

- 3.3. Statistical Tests

- 3.3.1. General Test Procedures for Studying Random Data

- 3.3.2. Empirical Tests

- 3.3.3. Theoretical Tests

- 3.3.4. The Spectral Test

- 3.4. Other Types of Random Quantities

- 3.4.1. Numerical Distributions

- 3.4.2. Random Sampling and Shuffling

- 3.5. What Is a Random Sequence?

- 3.6. Summary

- Chapter 4 – Arithmetic

- 4.1. Positional Number Systems

- 4.2. Floating Point Arithmetic

- 4.2.1. Single-Precision Calculations

- 4.2.2. Accuracy of Floating Point Arithmetic

- 4.2.3. Double-Precision Calculations

- 4.2.4. Distribution of Floating Point Numbers

- 4.3. Multiple Precision Arithmetic

- 4.3.1. The Classical Algorithms

- 4.3.2. Modular Arithmetic

- 4.3.3. How Fast Can We Multiply?

- 4.4. Radix Conversion

- 4.5. Rational Arithmetic

- 4.5.1. Fractions

- 4.5.2. The Greatest Common Divisor

- 4.5.3. Analysis of Euclid's Algorithm

- 4.5.4. Factoring into Primes

- 4.6. Polynomial Arithmetic

- 4.6.1. Division of Polynomials

- 4.6.2. Factorization of Polynomials

- 4.6.3. Evaluation of Powers (addition-chain exponentiation)

- 4.6.4. Evaluation of Polynomials

- 4.7. Manipulation of Power Series

Volume 3 – Sorting and Searching

- Chapter 5 – Sorting

- 5.1. Combinatorial Properties of Permutations

- 5.1.1. Inversions

- 5.1.2. Permutations of a Multiset

- 5.1.3. Runs

- 5.1.4. Tableaux and Involutions

- 5.2. Internal sorting

- 5.2.1. Sorting by Insertion

- 5.2.2. Sorting by Exchanging

- 5.2.3. Sorting by Selection

- 5.2.4. Sorting by Merging

- 5.2.5. Sorting by Distribution

- 5.3. Optimum Sorting

- 5.3.1. Minimum-Comparison Sorting

- 5.3.2. Minimum-Comparison Merging

- 5.3.3. Minimum-Comparison Selection

- 5.3.4. Networks for Sorting

- 5.4. External Sorting

- 5.4.1. Multiway Merging and Replacement Selection

- 5.4.2. The Polyphase Merge

- 5.4.3. The Cascade Merge

- 5.4.4. Reading Tape Backwards

- 5.4.5. The Oscillating Sort

- 5.4.6. Practical Considerations for Tape Merging

- 5.4.7. External Radix Sorting

- 5.4.8. Two-Tape Sorting

- 5.4.9. Disks and Drums

- 5.5. Summary, History, and Bibliography

- 5.1. Combinatorial Properties of Permutations

- Chapter 6 – Searching

Volume 4A – Combinatorial Algorithms, Part 1

- Chapter 7 – Combinatorial Searching

- 7.1. Zeros and Ones

- 7.1.1. Boolean Basics

- 7.1.2. Boolean Evaluation

- 7.1.3. Bitwise Tricks and Techniques

- 7.1.4. Binary Decision Diagrams

- 7.2. Generating All Possibilities

- 7.2.1. Generating Basic Combinatorial Patterns

- 7.2.1.1. Generating all n-tuples

- 7.2.1.2. Generating all permutations

- 7.2.1.3. Generating all combinations

- 7.2.1.4. Generating all partitions

- 7.2.1.5. Generating all set partitions

- 7.2.1.6. Generating all trees

- 7.2.1.7. History and further references

- 7.2.1. Generating Basic Combinatorial Patterns

- 7.1. Zeros and Ones

Volume 4B – Combinatorial Algorithms, Part 2

- Chapter 7 – Combinatorial Searching (continued)

- 7.2. Generating all possibilities (continued)

- 7.2.2. Backtrack programming

- 7.2.2.1. Dancing links (includes discussion of Exact cover)

- 7.2.2.2. Satisfiability

- 7.2.2. Backtrack programming

- 7.2. Generating all possibilities (continued)

Volumes 4C, 4D, 4E, 4F – Combinatorial Algorithms[14]

- Chapter 7 – Combinatorial Searching (continued)

- 7.2. Generating all possibilities (continued)

- 7.2.2. Backtrack programming (continued)

- 7.2.2.3. Constraint satisfaction

- 7.2.2.4. Hamiltonian paths and cycles

- 7.2.2.5. Cliques

- 7.2.2.6. Covers (Vertex cover, Set cover problem, Exact cover, Clique cover)

- 7.2.2.7. Squares

- 7.2.2.8. A potpourri of puzzles (includes Perfect digital invariant)

- 7.2.2.9. Estimating backtrack costs (chapter 6 of "Selected Papers on Analysis of Algorithms", and Fascicle 5, pp. 44−47, under the heading "Running time estimates")

- 7.2.3. Generating inequivalent patterns (includes discussion of Pólya enumeration theorem) (see "Techniques for Isomorph Rejection", chapter 4 of "Classification Algorithms for Codes and Designs" by Kaski and Östergård)

- 7.2.2. Backtrack programming (continued)

- 7.3. Shortest paths

- 7.4. Graph algorithms

- 7.4.1. Components and traversal

- 7.4.1.1. Union-find algorithms

- 7.4.1.2. Depth-first search

- 7.4.1.3. Vertex and edge connectivity

- 7.4.2. Special classes of graphs

- 7.4.3. Expander graphs

- 7.4.4. Random graphs

- 7.4.1. Components and traversal

- 7.5. Graphs and optimization

- 7.5.1. Bipartite matching (including maximum-cardinality matching, Stable marriage problem, Mariages Stables)

- 7.5.2. The assignment problem

- 7.5.3. Network flows

- 7.5.4. Optimum subtrees

- 7.5.5. Optimum matching

- 7.5.6. Optimum orderings

- 7.6. Independence theory

- 7.6.1. Independence structures

- 7.6.2. Efficient matroid algorithms

- 7.7. Discrete dynamic programming (see also Transfer-matrix method)

- 7.8. Branch-and-bound techniques

- 7.9. Herculean tasks (aka NP-hard problems)

- 7.10. Near-optimization

- 7.2. Generating all possibilities (continued)

- Chapter 8 – Recursion (chapter 22 of "Selected Papers on Analysis of Algorithms")

Volume 5 – Syntactic Algorithms

- Chapter 9 – Lexical scanning (includes also string search and data compression)

- Chapter 10 – Parsing techniques

English editions

Current editions

These are the current editions in order by volume number:

- The Art of Computer Programming, Volumes 1-4B Boxed Set. (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 2023), 3904pp. ISBN 978-0-13-793510-9, 0-13-793510-2

- Volume 1: Fundamental Algorithms. Third Edition (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1997), xx+650pp. ISBN 978-0-201-89683-1, 0-201-89683-4. Errata: (2011-01-08), (2022, 49th printing). Addenda: (2011).

- Volume 2: Seminumerical Algorithms. Third Edition (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1997), xiv+762pp. ISBN 978-0-201-89684-8, 0-201-89684-2. Errata: (2011-01-08), (2022, 45th printing). Addenda: (2011).

- Volume 3: Sorting and Searching. Second Edition (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1998), xiv+780pp.+foldout. ISBN 978-0-201-89685-5, 0-201-89685-0. Errata: (2011-01-08), (2022, 45th printing). Addenda: (2011).

- Volume 4A: Combinatorial Algorithms, Part 1. First Edition (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Addison-Wesley, 2011), xv+883pp. ISBN 978-0-201-03804-0, 0-201-03804-8. Errata: (2011), (2022, 22nd printing).

- Volume 4B: Combinatorial Algorithms, Part 2. First Edition (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Addison-Wesley, 2023), xviii+714pp. ISBN 978-0-201-03806-4, 0-201-03806-4. Errata: (2023, 1st printing).

- Volume 1, Fascicle 1: MMIX – A RISC Computer for the New Millennium. (Addison-Wesley, 2005-02-14) ISBN 0-201-85392-2. Errata: (2020-03-16) (will be in the fourth edition of volume 1)

Complete volumes

These volumes were superseded by newer editions and are in order by date.

- Volume 1: Fundamental Algorithms. First edition, 1968, xxi+634pp, ISBN 0-201-03801-3.[16]

- Volume 2: Seminumerical Algorithms. First edition, 1969, xi+624pp, ISBN 0-201-03802-1.[16]

- Volume 3: Sorting and Searching. First edition, 1973, xi+723pp+foldout, ISBN 0-201-03803-X. Errata: .

- Volume 1: Fundamental Algorithms. Second edition, 1973, xxi+634pp, ISBN 0-201-03809-9. Errata: .

- Volume 2: Seminumerical Algorithms. Second edition, 1981, xiii+ 688pp, ISBN 0-201-03822-6. Errata: .

- The Art of Computer Programming, Volumes 1-3 Boxed Set. Second Edition (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1998), pp. ISBN 978-0-201-48541-7, 0-201-48541-9

- The Art of Computer Programming, Volumes 1-4A Boxed Set. Third Edition (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 2011), 3168pp. ISBN 978-0-321-75104-1, 0-321-75104-3

Fascicles

Volume 4, Fascicles 0–4 were revised and published as Volume 4A.

- Volume 4, Fascicle 0: Introduction to Combinatorial Algorithms and Boolean Functions. (Addison-Wesley Professional, 2008-04-28) vi+240pp, ISBN 0-321-53496-4. Errata: (2011-01-01).

- Volume 4, Fascicle 1: Bitwise Tricks & Techniques; Binary Decision Diagrams. (Addison-Wesley Professional, 2009-03-27) viii+260pp, ISBN 0-321-58050-8. Errata: (2011-01-01).

- Volume 4, Fascicle 2: Generating All Tuples and Permutations. (Addison-Wesley, 2005-02-14) v+127pp, ISBN 0-201-85393-0. Errata: (2011-01-01).

- Volume 4, Fascicle 3: Generating All Combinations and Partitions. (Addison-Wesley, 2005-07-26) vi+150pp, ISBN 0-201-85394-9. Errata: (2011-01-01).

- Volume 4, Fascicle 4: Generating All Trees; History of Combinatorial Generation. (Addison-Wesley, 2006-02-06) vi+120pp, ISBN 0-321-33570-8. Errata: (2011-01-01).

Volume 4, Fascicles 5–6 were revised and published as Volume 4B.

Pre-fascicles

Volume 1

- Pre-fascicle 1 was revised and published as Volume 1, fascicle 1.

Volume 4

- Pre-fascicles 0A, 0B, and 0C were revised and published as Volume 4, fascicle 0.

- Pre-fascicles 1A and 1B were revised and published as Volume 4, fascicle 1.

- Pre-fascicles 2A and 2B were revised and published as Volume 4, fascicle 2.

- Pre-fascicles 3A and 3B were revised and published as Volume 4, fascicle 3.

- Pre-fascicles 4A and 4B were revised * and published as Volume 4, fascicle 4.

- Pre-fascicles 5A, 5B, and 5C were revised and published as Volume 4, fascicle 5.

- Pre-fascicle 6A was revised and published as Volume 4, fascicle 6.

The remaining pre-fascicles contain draft material that is set to appear in future fascicles and volumes.

- Volume 4, Pre-fascicle 7A: Constraint Satisfaction

- Volume 4, Pre-fascicle 8A: Hamiltonian Paths and Cycles

- Volume 4, Pre-fascicle 8B: Cliques

- Volume 4, Pre-fascicle 9B: A Potpourri of Puzzles

- Volume 4, Pre-fascicle 9C: Estimating Backtrack Costs

- Volume 4, Pre-fascicle 12A: Components and Traversal (PDF Version)

- Volume 4, Pre-fascicle 14A: Bipartite Matching

- Volume 4, Pre-fascicle 16A: Introduction to Recursion

See also

References

Notes

- The dedication was worded slightly differently in the first edition.

Citations

- "note for box 3, folder 1".

- "Pearson InformIT webpage book Content tab".

- "Pearson InformIT webpage".

- "CP 2022 All Questions Answered, July 31–August 5, 2022, Haifa, Israel".

- Frana, Philip L. (2001-11-08). "An Interview with Donald E. Knuth". hdl:11299/107413.

- Knuth, Donald E. (1993-08-23). "This Week's Citation Classic" (PDF). Current Contents. p. 8.

- Albers, Donald J. (2008). "Donald Knuth". In Albers, Donald J.; Alexanderson, Gerald L. (eds.). Mathematical People: Profiles and Interviews (2 ed.). A. K. Peters. ISBN 978-1-56881-340-0.

- "Reflections on a year of reading Knuth". infinitepartitions.com. Retrieved 2020-07-25.

I worked, or at least attempted to work, every single problem in the first volume. In some cases I settled for just understanding what the question was trying to ask for. In some cases I failed even to accomplish that (don't judge me until you try it yourself). Each problem is assigned a difficulty rating from 0-50 where 0 is trivial and 50 is "unsolved research problem" (in the first edition, Fermat's last theorem was listed as a 50, but since Andrew Wiles proved it, it's bumped down to a 45 in the current edition). I think I was able to solve most of the problems rated < 20 — it was hit and miss beyond that. Most of the problems fell into the 20-30 difficulty range, but Knuth's idea of "difficult" is subjective, and problems that he considers to be of average difficulty ended up stretching my comparatively tiny brain painfully. I've never climbed Mount Everest, but I imagine the whole ordeal feels similar: painful while you're going through it, but triumphant when you reach the pinnacle.

- "GNU MDK - GNU Project - Free Software Foundation". www.gnu.org. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- "Donald E. Knuth – A. M. Turing Award Winner". AM Turing. Retrieved 2017-01-25.

- Morrison, Philip; Morrison, Phylis (November–December 1999). "100 or so Books that shaped a Century of Science". American Scientist. Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society. 87 (6). Archived from the original on 2008-08-20. Retrieved 2008-01-11.

- Weinberger, Matt. "Bill Gates once said 'definitely send me a résumé' if you finish this fiendishly difficult book". Business Insider. Retrieved 2016-06-13.

- Lohr, Steve (2001-12-17). "Frances E. Holberton, 84, Early Computer Programmer". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- D'Agostino, Susan (2020-04-16). "The Computer Scientist Who Can't Stop Telling Stories". Quanta Magazine. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

Now 82, he's hard at work on part B of volume 4, and he anticipates that the book will have at least parts A through F.

- "TAOCP – Future plans".

- Wells, Mark B. (1973). "Review: The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1. Fundamental Algorithms and Volume 2. Seminumerical Algorithms by Donald E. Knuth" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 79 (3): 501–509. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1973-13173-8.

Sources

- Slater, Robert (1987). Portraits in Silicon. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-19262-4.

- Shasha, Dennis; Lazere, Cathy (1995). Out of Their Minds: The Lives and Discoveries of 15 Great Computer Scientists. Copernicus. ISBN 0-387-97992-1.

External links

- Overview of topics (Knuth's personal homepage)

- Oral history interview with Donald E. Knuth at Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Knuth discusses software patenting, structured programming, collaboration and his development of TeX. The oral history discusses the writing of The Art of Computer Programming.

- "Robert W Floyd, In Memoriam", by Donald E. Knuth - (on the influence of Bob Floyd)

- TAoCP and its Influence of Computer Science (Softpanorama)