Taiwanese tea

Taiwanese tea includes four main types: oolong tea, black tea, green tea and white tea. The earliest record of tea trees found in Taiwan is from 1717 in Shui Sha Lian (水沙連), present-day Yuchi and Puli, Nantou County.[1] Some of the teas retain the island country's former name, Formosa.

Oolongs grown in Taiwan account for about 20% of world production.[2]

History

According to Lian Heng's General History of Taiwan, in the late 18th century, Ke Chao (柯朝) brought some tea trees from Fujian into Taiwan and planted them in Jieyukeng (櫛魚坑), in the area of modern-day Ruifang District, New Taipei City. However, transaction records indicate that tea business in Muzha area started as early as late 18th century. These records indicate that tea has been sold in Taiwan for more than two centuries.

In 1855, Lin Fengchi (林鳳池) brought the Qingxin oolong (青心烏龍) plants from the Wuyi Mountains of Fujian to Taiwan and planted them in Dongding Village (Lugu, Nantou County). This is said to be the origin of Tung-ting tea.

After the Treaty of Tientsin was ratified in 1860 and the port of Tamsui was opened for trade, Scottish entrepreneur John Dodd began working with tea merchants and farmers to promote Taiwanese tea, slowly developing it as an export item. Before long, tea ranked first among Taiwan's top three exports, ahead of sugar and camphor. The earliest teas exported during the Qing dynasty were oolong and baozhong tea, which began to be sold abroad in 1865 and 1881, respectively.[3]

In 1867, Dodd started a tea company in Wanhua, Taipei and started to sell Taiwanese oolong tea to the world under the name "Formosa Oolong". Aware of British plans to develop a tea industry in India, he successfully sought profit in developing an alternative tea product on the island.[4] Pouchong oolong was considered to be more flowery than Baihao oolong. Pouchong was exported under the name "Formosa Pouching". Other types of Taiwanese Oolongs include Dongding oolong (凍頂烏龍茶), white tip oolong (白毫烏龍茶), and baochong oolong (包種烏龍茶). Oolong tea was practically synonymous with Taiwanese tea in the late 19th century, and competitors in Ceylon sought a US market advantage by publishing materials emphasizing the use of human foot trampling during its production.[5] This was countered by the mechanization of tea processing, publicized at the St. Louis Exhibition.[5]

After acquiring Taiwan the Japanese set out to turn their new colonial possession into “another Darjeeling.” Formal efforts began in 1906 with early production exported to Turkey and Russia. The Mitsui Corporation led development of the industry in the north however they found the region to be unsuitable for the major tea varieties from Assam and Sri Lanka. In the 1920s plantations of Indian tea varieties were developed in Yuchi Township, Nantou County. In 1926 the Yuchi Black Tea Research Institute was founded. The Research Institute focused on hybridizing commercial tea varieties with Taiwan's indigenous varieties. The development of the industry continued through World War II. After the war Yuchi Black Tea Research Institute head Kokichiro Arai staying on under the Kuomintang regime. The industry continued to expand until the 1960s before declining. After the 1999 Jiji earthquake the government paid heavily to rebuild the industry.[6]

China was subject to trade embargos during the 1950s and 1960s, and during this time Taiwanese tea growers and marketers focused on existing, well-known varieties.[7] After the mainland's products became more widely available and the market for teas became more competitive, the Taiwanese tea industry changed its emphasis to producing special varieties of tea, especially of Oolong.[7] The Government Tea Inspection Office grades teas into 18 categories ranging from standard to choice.[8]

The government-supported Tea Research and Extension Station, established to promote Taiwanese tea in 1903, conducts research and experimentation.[9]

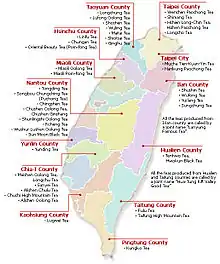

Tea areas

Major tea growing areas:

- Northern Taiwan: Includes Hsindian, Pinglin, Muzha, Shenkeng, Shidian, Sanhsia, Nangang, and Yilan.

- Mid-central Area: Includes Miaoli and Hsinchu.

- Eastern Taiwan: Includes Taitung and Hualien.

- South-central Taiwan: Includes Nantou, Pingtung, Chiayi, Taichung, and Yunlin.

- High Mountain Regions: Includes Alishan, Yu Shan, Hsueh Shan, and Taitung mountain ranges.

Oolong teas

Taiwan's climate, along with the development of tea technology, has contributed to the production of high-quality teas. The best known ones include "Formosa Dongding oolong", "Formosa Alishan oolong", "Formosa Wenshan pouchong", "Formosa oriental beauty", "Formosa Shanlinxi oolong", and "Formosa jade oolong". According to the 1997 version of the Joy of Cooking, Taiwanese oolongs are considered to be some of the finest by tea connoisseurs.[10] The US cooks Julee Rosso and Sheila Lukins describe three Taiwanese oolongs as the "Champagne of tea".[11] Their special quality may be due to unique growing conditions.[8]

Oolong is harvested five times per year in Taiwan, between April and December.[8] The July and August crops generally receive the highest grades.[8]

Dongding Tea

This tea, grown on Dongding (凍頂) mountain in Nantou County, was brought to Taiwan during the 19th century from the mainland's Wuyi Mountains.[12] Its special qualities have been attributed to an almost continuous fog.[12] Teas harvested in the spring are entered in a competition and the winners go for premium prices, fetching US$2,000 for a 600-gram package during the 1990s.[12] Dongding oolong undergoes less oxidization than most oolongs.[2] A 40-minute roasting over charcoal contributes to its flavor, which also has "nutty, caramel, and chestnut" elements.[13][14]

Tongding Oolong tea is a semi-oxidized tea with a hemispherical shape, created through a baking process. The tea leaves are rolled into round balls through multiple kneading and undergo post-oxidization, resulting in a more pronounced flavor profile for Oolong tea.

Pouchong (or Baozhong) Tea

Pouchong oolong, also called light oolong, is a lightly oxidized tea, twist shape, with floral notes, and usually not roasted, somewhere between green tea and what is usually considered oolong tea (Chinese: 烏龍; pinyin: wǔlóng; lit. 'dark dragon'), though often classified with the latter due to its lack of the sharper green tea flavours. Pouchong refers to its paper wrapping.[15]

Oriental Beauty (Dongfang Meiren) Tea

White tip oolong is very fruity in taste and got the name "Oriental Beauty" from Queen Elizabeth II in the 1960s, thus "Formosa oolong" became popular in the western world for "oriental beauty" (東方美人茶). Along with Lishan oolong, it was one of the most costly exported Taiwanese teas during the 2000s.[13] Its unique flavor originates in part from the inclusion of insect eggs and egg sacs during harvesting, contributing an element that has been described as "earthier and more robust" than Earl Grey tea.[13] The acceptance of this flavor has led to tolerance of the presence of insects and organic growing practices for this tea.[13]

Iron Goddess (Tie Guanyin) Tea

This variety originated on the mainland, and is associated with a legend in which a tea grower found a unique tea plant near an iron statue of Kuan Yin.[16] Taiwan Muzha Iron Goddess tea (木柵鐵觀音), also known as Tie Guan Yin, is a traditional oolong. It is roasted and has a stronger taste and a roast nutty character; the tea liquid is reddish brown. Muzha Iron Goddess tea is different from Anxi Iron Goddess tea, which is not roasted and green in character.

High Mountain (Gao Shan) Teas

Also called Alpine oolong, grown at altitudes of 1,000 meters or above.

- Lishan (梨山) oolong

Grown at altitudes above 2,200 meters, was the costliest Taiwanese tea during the 2000s, sometimes commanding prices of over $200 USD per 600 grams.[13]

- Dayuling (大禹嶺) oolong

Grown at altitudes above 2,500 meters. Some people call it the king of Taiwan high mountain tea. Due to the limited production of this tea, the price per 500 grams is usually around $200 to $500 USD. Because of its popularity, there are unscrupulous businessmen selling fake/unqualified tea using Dayuling's brand name.

- Ali Mountain (阿里山), or other high mountains.

This is the most widely known general name for lightly oxidized oolong tea, much of it picked in winter and therefore termed “winter tea”. Among the oolongs grown on Ali Mountain, tea merchants tend to stress the special qualities of the gold lily (Chinese: 金萱; pinyin: Jin Xuan; Wade–Giles: Chin-Hsuan) tea variety, which is the name of a cultivar developed in Taiwan in the 1980s. The oolong tea made with this cultivar has a particular milky flavor. However, in some regions, such as where Alishan zhulu tea is grown, the most prized are the ones made with the Qing Xin cultivar. Tea made with this cultivar has a floral and ripe-fruity aroma.

Osmanthus Oolong

An oolong scented with osmanthus flowers, the tea is also packaged with some flowers added after the scenting process. This tea is roasted, with floral and warming notes.

Black tea

Black Jade Taiwan Tea TTES #18 is a cultivar developed by the Taiwan Tea Research and Experiment Station during the 1990s.[17] The now popular tea is a hybrid of Camellia sinensis v. assamica and a native variety (Camellia sinensis forma formosensis), and is said to have notes of honey, cinnamon, and mint.[17] The tea's natural sweetness is a result of the fostered relationship with insects. The native Leafhopper (Jacobiasca formosana) spends its time throughout the growing season laying eggs and biting the tea plant, which causes the plant to produce two compounds, monoterpene diol and hotrienol. This defense mechanism, in addition to Leafhopper eggs, results in this Taiwanese Black tea's unique flavor.

Green tea

Green tea, such as Dragon Well (Longjing tea) and Green Spiral (Biluochun), are grown in Sanxia District, New Taipei City.

Bubble tea

Bubble tea originated in Taiwan during the 1980s and is now popular worldwide.[18]

See also

- Taiwanese tea culture

- Tea Research and Extension Station Taiwan TRES

- Fo Shou tea

- Heike Matthiesen: „Taiwanesischer Tee. Teesorten, ihre Anbaugebiete sowie die jüngere Entwicklung des Teemarktes.“ Berlin 2005, 1. Auflage August 2020, grin.com: ISBN 978-3-346-21601-4 (Ebook), ISBN 978-3-346-21602-1 (Buch).

References

- Mark Anton Allee (1994), "Tea", Law and local society in late imperial China: northern Taiwan in the nineteenth century, Stanford University Press, pp. 97 et seq, ISBN 978-0-8047-2272-8

- "Agriculture - sectors". Government of Taiwan. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- "The Art of Tea". Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- Michael Harney (7 October 2008). The Harney & Sons Guide to Tea. Penguin. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-59420-138-7. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- Marcus Bourne Huish (1903). Fifty years of new Japan (Kiakoku gojūnen shi). Smith, Elder, & Co. p. 542. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- Cheung, Han. "Taiwan in Time: Taiwan's Darjeeling". taipeitimes.com. Taipei Times. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- Michael Harney (7 October 2008). The Harney & Sons Guide to Tea. Penguin. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-1-59420-138-7. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- Joel Schapira; David Schapira; Karl Schapira (15 March 1996). The book of coffee & tea: a guide to the appreciation of fine coffees, teas, and herbal beverages. Macmillan. pp. 212–213. ISBN 978-0-312-14099-1. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- "Tea Research and Extension Station". Tea Research and Extension Station. Archived from the original on 2012-07-20. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- Irma von Starkloff Rombauer; Marion Rombauer Becker; Ethan Becker; Maria Guarnaschelli (5 November 1997). Joy of cooking. Simon and Schuster. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-684-81870-2. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- Julee Rosso; Sheila Lukins; Michael McLaughlin (5 March 2007). Silver Palate Cookbook 25th Anniversary Edition. Workman Publishing. p. 406. ISBN 978-0-7611-4597-4. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- "Lost in the Fog:Touring Tungting Oolong Country". Academia Sinica. Retrieved 2011-03-18.

- Phil Macdonald (20 November 2007). Taiwan. National Geographic Books. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-4262-0145-5. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- Mary Lou Heiss; Robert J. Heiss (30 March 2010). The Tea Enthusiast's Handbook: A Guide to the World's Best Teas. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-58008-804-6. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- Kit Boey Chow; Ione Kramer (September 1990). All the tea in China. China Books. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-8351-2194-1. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- Laura C. Martin (10 April 2007). Tea: the drink that changed the world. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 219–220. ISBN 978-0-8048-3724-8. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- "Morphological Comparisons of Taiwan Native Wild Tea Plant (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze forma formosensis Kitamura) and Two Closely Related Taxa Using Numerical Methods" (PDF). Taiwania, 52(1): 70-83, 2007. Retrieved 2011-03-18.

- Janet A. Flammang (20 October 2009). The taste for civilization: food, politics, and civil society. University of Illinois Press. pp. 220. ISBN 978-0-252-07673-2. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

18. ^ Heike Matthiesen: „Taiwanesischer Tee. Teesorten, ihre Anbaugebiete sowie die jüngere Entwicklung des Teemarktes.“ Berlin 2005, 1. Auflage August 2020, grin.com: ISBN 978-3-346-21601-4 (Ebook), ISBN 978-3-346-21602-1 (Buch).

External links

- 台北市茶商業同業公會

- 預見,行銷全球的未來!- 以Formosa 之名行銷農產品於世界,農訓雜誌,2006,23(7): 22-25

- Taiwanese Oolong Tea

- Han Cheung (12 June 2022). "Taiwan in Time: Taiwan's Darjeeling". Taipei Times. Retrieved 12 June 2022.