Swahili coast

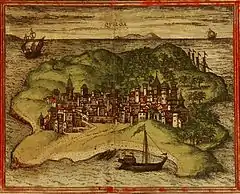

The Swahili coast (Swahili: Pwani ya Waswahili) is a coastal area of the Indian Ocean in East Africa inhabited by the Swahili people. It includes Dar es Salaam; Sofala (located in Mozambique); Mombasa, Gede, Pate Island, Lamu, and Malindi (in Kenya); and Kilwa (in Tanzania).[1] In addition, several coastal islands are included in the Swahili coast such as Zanzibar and Comoros.

Swahili coast

Pwani ya Waswahili (Swahili) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 6.8113°S 39.2844°E | |

| Countries | Tanzania Kenya Mozambique Comoros |

| Major cities | Dar es Salaam (Mzizima) Malindi Mombasa Sofala Lamu Zanzibar |

| Ethnic groups | |

| • Bantu | Swahili |

Areas of what is today considered the Swahili coast were historically known as Azania or Zingion in the Greco-Roman era, and as Zanj or Zinj in Middle Eastern, Indian, and Chinese literature from the 7th to the 14th century.[2][3] The word "Swahili" means people of the coasts in Arabic and is derived from the word sawahil ("coasts").[4]

The Swahili people and their culture formed from a distinct mix of African and Arab origins.[4] The Swahilis were traders and merchants and readily absorbed influences from other cultures.[5] Historical documents including the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea and works by Ibn Battuta describe the society, culture, and economy of the Swahili coast at various points in its history. The Swahili coast has a distinct culture, demography, religion, and geography, and as a result—along with other factors, including economic—has witnessed rising secessionism.[6]

History

In the pre-Swahili period, the region was occupied by smaller societies whose main socioeconomic activities were pastoralism, fishing, and mixed farming.[7] Early on, those living on the Swahili coast prospered because of agriculture helped by regular yearly rainfall and animal husbandry.[4] The shallow coast was important as it provided seafood.[4] Starting in the early 1st millennium CE, trade was crucial.[4][8] Submerged river estuaries created natural harbors as well as the yearly monsoon winds helped trade.[4][8] Later in the 1st millennium there was a huge migration of Bantu people.[4] The communities settling along the coast shared archaeological and linguistic features with those from the interior of the continent. Archeological data has revealed the use of Kwale and Urewe ceramics both along the coast and within the interior parts, showing that the regions had a shared way of life in the Late Stone and Early Iron Ages.[7]

From the earliest times of which there is any record the African seaboard from the Red Sea to an unknown distance southwards was subject to Arabian influence and dominion. At a later period the coast towns were founded or conquered by Persian and Arabs who, for the most part, fled to East Africa between the 8th and 11th centuries on account of the religious differences of the times, the refugees being schismatics. Various small states thus grew up along the coast, they are sometimes spoken of as the Zanj empire, though they were never, probably, united under one ruler.[9]

According to Berger et al., this shared way of life began to diverge at least around 13th century CE (362). In the wake of trading activities along the coast, Arab merchants would pour scorn on non-Muslims and some African practices. This attitude of scorn allegedly pushed African elites to deny connections to the interior and to claim descent from Shirazis and to have already converted to Islam. The interactions that ensued led to the formation of the unique Swahili culture and city states, especially those facilitated by trade.[10]

At the zenith of its power in the 15th century, the Kilwa Sultanate owned or claimed overlordship over the mainland cities of Malindi, Inhambane and Sofala and the island-states of Mombassa, Pemba, Zanzibar, Mafia, Comoro and Mozambique (plus numerous smaller places).[11]

The voyage of Vasco da Gama around the Cape of Good Hope into the Indian Ocean in 1498 marked the Portuguese entry into trade, politics, and society in the Indian Ocean world. The Portuguese gained control of the Island of Mozambique and the port city of Sofala in the early 16th century. Vasco da Gama having visited Mombasa in 1498 was then successful in reaching India thereby permitting the Portuguese to trade with the Far East directly by sea, thus challenging older trading networks of mixed land and sea routes, such as the spice trade routes that used the Persian Gulf, Red Sea and caravans to reach the eastern Mediterranean. Initially, Portuguese rule in East Africa focused mainly on a coastal strip centred in Mombasa. With voyages led by Vasco da Gama, Francisco de Almeida and Afonso de Albuquerque, the Portuguese dominated much of southeast Africa's coast, including Sofala and Kilwa, by 1515.

The Portuguese were able to wrest much of the coastal trade from Arabs between 1500 and 1700, but, with the Arab seizure of Portugal's key foothold at Fort Jesus on Mombasa Island (now in Kenya) in 1698 by Omani ruler Saif bin Sultan, the Portuguese had to retreat south.[12]

Omani ruler Said bin Sultan (1806–1856) moved his court from Muscat to Stone Town on the island of Unguja (that is, Zanzibar Island). He established a ruling Arab elite and encouraged the development of clove plantations, using the island's slave labour. As a regional commercial power in the 19th century, Oman held the island of Zanzibar and the Zanj region of the East African coast, including Mombasa and Dar es Salaam.

When Said ibn Sultan died in 1856, his sons quarrelled over the succession. As a result of this struggle, the empire was divided in 1861 into two separate principalities: Sultanate of Zanzibar and the area of "Muscat and Oman".[13]

Until 1884, the Sultans of Zanzibar controlled a substantial portion of the Swahili Coast, known as Zanj. That year, however, the Society for German Colonization forced local chiefs on the mainland to agree to German protection, prompting Sultan Bargash bin Said to protest. Coinciding with the Berlin Conference and the Scramble for Africa, further German interest in the area was soon shown in 1885 by the arrival of the newly created German East Africa Company, which had a mission to colonize the area.

In 1886, the British and Germans secretly met and discussed their aims of expansion in the African Great Lakes, with spheres of influence already agreed upon the year before, with the British to take what would become the East Africa Protectorate (now Kenya) and the Germans to take present-day Tanzania. Both powers leased coastal territory from Zanzibar and established trading stations and outposts. Over the next few years, all of the mainland possessions of Zanzibar came to be administered by European imperial powers, beginning in 1888 when the Imperial British East Africa Company took over administration of Mombasa.

The same year the German East Africa Company acquired formal direct rule over the coastal area previously submitted to German protection. This resulted in a native uprising, the Abushiri revolt, which was suppressed by the Kaiserliche Marine and heralded the end of Zanzibar's influence on the mainland.

With the signing of the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty between the United Kingdom and the German Empire in 1890, Zanzibar itself became a British protectorate. In August 1896, following the death of Sultan Hamad bin Thuwaini, Britain and Zanzibar fought a 38-minute war, the shortest in recorded history. A struggle for succession took place as the Sultan's cousin Khalid bin Barghash seized power. The British instead wanted Hamoud bin Mohammed to become Sultan, believing that he would be much easier to work with. The British gave Khalid an hour to vacate the Sultan's palace in Stone Town. Khalid failed to do so, and instead assembled an army of 2,800 men to fight the British. The British launched an attack on the palace and other locations around the city after which Khalid retreated and later went into exile. Hamoud was then peacefully installed as Sultan.[14]

In 1886, the British government encouraged William Mackinnon, who already had an agreement with the Sultan and whose shipping company traded extensively in the African Great Lakes, to increase British influence in the region. He formed a British East Africa Association which led to the Imperial British East Africa Company being chartered in 1888 and given the original grant to administer the territory. It administered about 240 km (150 mi) of coastline stretching from the River Jubba via Mombasa to German East Africa which were leased from the Sultan. However, the company began to fail, and on 1 July 1895 the British government proclaimed a protectorate, the East Africa Protectorate, the administration being transferred to the Foreign Office.[15]

In 1891, after it became apparent that the German East Africa Company could not handle its dominions, it sold out to the German government, which began to rule German East Africa directly. During World War I German East Africa was gradually occupied by forces from the British Empire and Belgian Congo during the East Africa Campaign, although German resistance continued until 1918. After this, the League of Nations formalised control of the area by the UK, who renamed it "Tanganyika". The UK held Tanganyika as a League of Nations mandate until the end of World War II after which it was held as a United Nations trust territory.

On 23 July 1920, the inland areas of the East Africa Protectorate were annexed as British dominions by Order in Council.[16] That part of the former Protectorate was thereby constituted as the Colony of Kenya and from that time, the Sultan of Zanzibar ceased to be sovereign over that territory. The remaining 16 km (10 mi) wide coastal strip (with the exception of Witu) remained a Protectorate under an agreement with the Sultan of Zanzibar.[17] That coastal strip, remaining under the sovereignty of the Sultan of Zanzibar, was constituted as the Protectorate of Kenya in 1920.[18][19]

In 1961, Tanganyika gained its independence from the UK as Tanganyika, joining the Commonwealth. It became a republic a year later.

The Colony of Kenya came to an end in 1963 when an ethnic Kenyan majority government was elected for the first time and eventually declared independence.

On 10 December 1963, the Protectorate that had existed over Zanzibar since 1890 was terminated by the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom did not grant Zanzibar independence, as such, because the UK never had sovereignty over Zanzibar. Rather, by the Zanzibar Act 1963 of the United Kingdom,[20] the UK ended the Protectorate and made provision for full-self government in Zanzibar as an independent country within the Commonwealth. Upon the Protectorate being abolished, Zanzibar became a constitutional monarchy within the Commonwealth under the Sultan. Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah was overthrown a month later during the Zanzibar Revolution. Jamshid fled into exile, and the Sultanate was replaced by the People's Republic of Zanzibar. In April 1964, the existence of this socialist republic was ended with its union with Tanganyika to form the United Republic of Tanganyika and Zanzibar, which became known as Tanzania six months later.

Indian Ocean trade

Trade along the Eastern African coast started as early as the first century CE. Bantu farmers, who are considered the initial settlers within the region, built communities along the coast. These farmers eventually started trading with traders from southeast Asia, southern Arabia, and sometimes Rome and Greece (Berger et al. 362). The rise of the Swahili coast city-states can be largely attributed to the region's extensive participation in a trade network that spanned the Indian Ocean.[21][22] The Indian Ocean's trade network has been likened to that of the Silk Road, with many destinations being linked through trade. It has been claimed that the Indian Ocean trade network actually connected more people than the Silk Road.[8] The Swahili coast largely exported raw products like timber, ivory, animal skins, spices, and gold.[8] Finished products were imported from as far as east Asia such as silk and porcelain from China, spices and cotton from India, and black pepper from Sri Lanka.[23] Some of the other imports received from Asia and Europe include cottons, silks, woolens, glass and stone beads, metal wire, jewelry, sandalwood, cosmetics, fragrances, kohl, rice, spices, coffee, tea, other foods and flavorings, teak, iron and brass fittings, sailcloth, pottery, porcelain, silver, brass, glass, paper, paints, ink, carved wood, books, carved chests, arms, ammunition, gunpowder, swords and daggers, gold, silver, brass, bronze, religious specialists, and craftsmen.[21] Other places that traded with the Swahili coast include Egypt, Greece, Rome, Assyria, Sumeria, Phoenicia, Arabia, Somalia, and Persia.[24] Trade in the region decreased during the Pax Mongolica due to overland trade being cheaper during that period, however, trade by ships provided the advantage that the goods that were transported on them were in bulk, meaning they could be available to the mass market.[8] Many different ethnic groups were involved in the Indian Ocean's trade network, however, especially in the western part of the Indian Ocean, Swahili coast being included, Muslim merchants dominated trade due to their ability to fund the construction of vessels.[8] The yearly monsoon winds carried ships from the Swahili coast to the eastern Indian Ocean and back. These yearly winds were the catalyst for trade in the region as they reduced the risk associated with sailing and made it predictable. The monsoon winds were less strong and reliable as one travelled further South along Africa's coast resulting in settlements being smaller and less frequent towards the South.[4] Trade was further encouraged by the invention of lateen sails which allowed merchants to travel apart from the monsoon winds.[8] Evidence for Indian Ocean trade includes the presence of pot shards on coastal archaeological sites that can be traced back to China and India.[25]

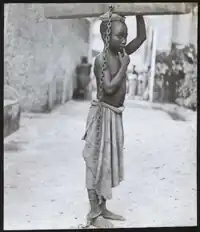

Slave trade

It has been estimated that between 1450 and 1900 CE as many as 17 million people were sold into slavery from Europe, Africa, and Asia and transported by Asian slave traders through the Mediterranean Sea, Silk Road, Indian Ocean, Red Sea, and Sahara desert to distant locations. As many as 5 million of these may have come from Africa, though most would have been from West Africa, rather than East Africa.[26] Before the 18th Century, the slave trade on the East African coast was fairly minor. Women and children were preferred since the main roles of enslaved persons in the Asian World were as domestic servants and concubines. Most of the enslaved would have been absorbed into Swahili households. The children of enslaved concubines were born as free members of their father's lineage without distinction and manumissions were a common act of piety for elderly Muslims.[27][28] A series of slave uprisings took place between 869 and 883 CE in Basra, a city of present-day Iraq, referred to as the Zanj Rebellion. The enslaved Zanj were likely transported from the more southern areas of East Africa.[29] The uprising grew to more than 500,000 slaves and free men as well, who were used in strenuous agriculture labor.[30] The Zanj Rebellion was a guerilla war mounted by slaves against the Abbasids. This revolt lasted 14 years. Slaves with numbers as high as 15,000 would raid towns, set slaves free, and seize weapons and food. These revolts greatly destabilized the grip that the Abbasids had over slaves. During the Rebellion, the slaves, under the leadership of Ali ibn Muhammad, captured Basra and even threatened to raid the capital, Baghdad.[10] The vast majority of the slave rebels were Black Africans, and the 9th century Zanj revolts in Iraq is some of the best evidence of a large number of people being sold into slavery from Eastern Africa. As a result of this uprising, Abbasid Caliphate largely abandoned the large-scale importation of slaves from East Africa.[31]

Coins

On the Swahili coast, coin minting can be correlated to an increase in Indian Ocean trade.[32] The earliest coins share many similarities to coins from Sindh. Some estimate that coins were minted on the Swahili coast as early as the mid 9th century until the end of the 15th century CE.[32] The making of coins came comparatively late to this area with many other cultures starting to make coins several centuries earlier. There are archaeological records of foreign coins being used in the area but few coins of foreign origin have been excavated. Previously, it was believed that the coins from the Swahili coast were of Persian origin, but now it is recognized that these are in fact indigenous coins.[32] The coins found on the coast only have inscriptions in Arabic, not Swahili. The coins from this region can be put into five categories: Shanga silver, Tanzanian silver, Kilwa copper, Kilwa gold and Zanzibar copper. Silver is not found locally on the Swahili coast, so the metal had to be imported.[32]

Coastal islands

There are many islands close to the Swahili coast including Zanzibar, Kilwa, Mafia and Lamu in addition to distant Comoros which is sometimes considered part of the Swahili coast. Several of these islands became very powerful through trade including Zanzibar and Kilwa. Before these islands became trade hubs, it is likely that the abundant local resources were very important to the islands' inhabitants. These resources include mangroves, fishing, and crustaceans.[33] Mangroves were important as they provided wood for boats. However, archaeological digs reveal that the culture of the Swahili people living on these islands was adapted to trade and their maritime surroundings quite early on.[33]

Kilwa

Although today Kilwa is in ruins, historically it was one of the most powerful city states on the Swahili coast.[5] One of the main exports along the Swahili coast was gold and in the 13th century the city of Kilwa took control of the gold trade from Banadir in modern-day Somalia.[34][35] By the mid-14th century the sultan of Kilwa was able to assert his power over several other city states. Kilwa levied a customs duty on the gold that was shipped north from Zimbabwe that stopped in Kilwa's port. In Kilwa's Husuni Kabwa, or Great Fort, there is evidence of gardens, a pool, and commercial activities. The fort served as a palace and area to store commercial goods and was built by sultan Al-Hasan Ibn Suleman.[5] The fort consists of a public courtyard, and a private area. Due to the intricate architecture present in Kilwa Ibn Battuta, a Moroccan explorer, described the town as "one of the most beautiful towns in the world."[4] Although Kilwa had been trading for centuries, the city's wealth and control of the gold trade attracted the Portuguese who were in search of gold. During the period of Portuguese subjugation, trade essentially stopped in Kilwa.[5]

Zanzibar

Today, Zanzibar is a semi-autonomous region of Tanzania made up of the Zanzibar Archipelago. The archipelago is 25-50 kilometers (16-31 mi) from the mainland. Its main industries are tourism, spice production such as cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, and black pepper, and raffia palm trees.[36] In 1698, Zanzibar became part of the Omani sultanate after sultan Saif bin Sultan defeated the Portuguese at Mombasa. In 1832 the sultan of Oman moved his capital from Muscat to Stone Town, the main city of the Zanzibar archipelago.[37] He encouraged the creation of clove plantations as well as the settlement of Indian traders. Until 1890 the sultans of Zanzibar controlled part of the Swahili coast known as Zanj which included Mombasa and Dar es Salaam. At the end of the 19th century, the British and German empires brought Zanzibar into their spheres of influence.[38]

Culture

The culture of the Swahili coast had unique characteristics emerging from the diversity of its founders. The Swahili coast was essentially an urban civilization which revolved around trade activities.[7] A few individuals in the Swahili coast were wealthy and made up the elite, ruling class. These elite families were instrumental in the fashioning of Swahili urban life by establishing a Muslim ancestry, embracing Islam, financing mosques in the region, stimulating trade, and practicing the seclusion of women. The majority of the people in the Swahili coast were less wealthy and engaged in such jobs as clerks, craftsmen, sailors, and artisans.[7] The Swahili culture is predominantly Islamic by religion. Archeological records have shown that mosques in the Swahili cities were built as early as the eight century CE. Muslim burial grounds of similar age have also been discovered.[10] Despite being predominantly Muslim, the culture was distinctly African as indicated by the Swahili language used. This language was largely African characterized by many Arab and Persian words. Irrespective of their economic status, the Swahili drew a clear difference between them and the people from interior of the continent whom they considered as uncultured. For the elite, this distinction was important in selling into slavery Africans from neighboring, non-Muslim communities.[10] Fish and shellfish are common in the Swahili coast's food due to its proximity and reliance on the coast.[39] In addition, coconuts and many different spices as well as tropical fruits are often used. The Arabic influence can be seen in the small cups of coffee that are available in the area and the sweet meats that can be tasted. The Arab influence is also seen in the Swahili language, architecture, and boat design including food as aforementioned.[23]

Language

Swahili is the lingua franca of East Africa and the national language of Kenya and Tanzania in addition to being one of the languages of the African Union.[4][40] Estimates of the number of speakers vary greatly but are usually around 50, 80 and 100 million people.[41] Swahili is a Bantu language with heavy influence from Arabic with the word "Swahili" itself descending from the Arabic word "sahil," meaning "coast"; "Swahili" meaning "people of the coast."[4][42] Some hold that Swahili is a completely Bantu language with only a few Arabic loanwords, while others suggest that Bantu and Arabic mixed to form Swahili.[42] It has been hypothesized that the mixing of languages was facilitated by intermarriage between natives and Arabs in addition to general interactions.[42] Most likely, Swahili was around in some form before Arab contact but then was heavily influenced. Swahili syntax is very similar to that of other Bantu languages as, like other Bantu languages, Swahili has five vowels (a,e,i,o,u).[42]

Religion

The primary religion of the Swahili coast is Islam.[4][43] Initially, unorthodox Muslims fleeing persecution in their homelands may have settled in the region, but it is likely that the religion took hold through Arab traders.[4] The majority of Muslims on the Swahili coast are Sunni, but many people continue non-Islamic traditions.[4] For example, spirits who bring illness and misfortune are appeased and people are buried with valuable items. In addition, teachers of Islam are allowed to become medicine men; having medicine men being a practice carried over from local tribal religions.[4][43] Men wear protective amulets with Quran verses.[43] The historian P. Curtis said about Islam and the Swahili coast, "The Muslim religion ultimately became one of the central elements of Swahili identity."[4]

Architecture

The earliest known Mosques on the Swahili coast were built of wood and date back to the 9th century CE.[4] Swahili Mosques are typically smaller than elsewhere in the Muslim world and have little decorations.[4] In addition, they typically do not have minarets or inner courtyards.[4] Domestic housing was usually constructed of mud-bricks and were mostly one storey high.[4] Often, they had two long and narrow rooms.[4] Housing is often decorated by carved door frames and window grilles. Larger houses sometimes have gardens and orchards.[4] Houses were constructed close together which resulted in twisty narrow streets.[4]

See also

References

- Kemezis, K., 2010. East African City States (1000-1500). Blackpast.org. Available at: <https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/east-african-city-states/> [Accessed 23 April 2020].

- Felix A. Chami, "Kaole and the Swahili World," in Southern Africa and the Swahili World (2002), 6.

- A. Lodhi (2000), Oriental influences in Swahili: a study in language and culture contacts, ISBN 978-9173463775, pp. 72-84

- "Swahili Coast". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2019-11-14.

- Kilwa Kisiwani, Tanzania, retrieved 2019-10-30

- "Contagion of discontent: Muslim extremism spreads down east Africa coastline," The Economist (3 November 2012)

- LaViolette, Adria. Swahili Coast, In: Encyclopedia of Archaeology, ed. by Deborah M. Pearsall. (2008): 19-21. New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Int'l Commerce, Snorkeling Camels, and The Indian Ocean Trade: Crash Course World History #18, archived from the original on 2021-12-15, retrieved 2019-10-30

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Berger, Eugene, et al. World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500. University of North Georgia Press, 2016.

- Kevin Shillington (1995). History of Africa. St. Martin's press. pp. 126. ISBN 978-0312125981.

- "Brief History of Fort Jesus". www.mombasa-city.com. Retrieved 2022-04-03.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Cana, Frank Richardson (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 604–606.

- Kenya (Annexation) Order in Council, 1920, S.R.O. 1902 No. 661, S.R.O. & S.I. Rev. 246.

- Agreement of 14 June 1890: State pp. vol. 82. p. 653

- Kenya Protectorate Order in Council, 1920 S.R.O. 1920 No. 2343, S.R.O. & S.I. Rev. VIII, 258, State Pp., Vol. 87 p. 968

- Zanzibar Act 1963: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1963/55/contents/

- Horton, Mark; Middleton, John (2000). The Swahili: The social landscape of a mercantile society. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 063118919X.

- Philippe Beaujard "East Africa, the Comoros Islands and Madagascar before the sixteenth century, Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa" (2007)

- "AFRICA - Explore the Regions - Swahili Coast". www.thirteen.org. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- Finke, Jens (2010-01-04). The Rough Guide to Tanzania. Penguin. ISBN 9781405380188.

isbn:1405380187.

- BBC Kilwa Pot Sherds http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/about/transcripts/episode60/

- "Focus on the slave trade". BBC. 3 September 2001. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017.

- Suzuki, Hideaki. Slave Trade Profiteers In the Western Indian Ocean: Suppression and Resistance In the Nineteenth Century. 1st ed. 2017. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017.

- Alpers, Edward A. The Indian Ocean In World History. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Rodriguez, Junius P. (2007). Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion, Volume 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 585. ISBN 978-0313332739.

- "Islam, From Arab To Islamic Empire: The Early Abbasid Era". History-world.org. Archived from the original on 2012-10-11. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Asquith, Christina. "Revisiting the Zanj and Re-Visioning Revolt: Complexities of the Zanj Conflict – 868-883 Ad – slave revolt in Iraq". Archived from the original on 2016-03-06.

- Perkins, John (2015-12-25). "The Indian Ocean and Swahili Coast coins, international networks and local developments". Afriques. Débats, Méthodes et Terrains d'Histoire (6). doi:10.4000/afriques.1769. ISSN 2108-6796.

- Crowther, Alison; Faulkner, Patrick; Prendergast, Mary E.; Morales, Eréndira M. Quintana; Horton, Mark; Wilmsen, Edwin; Kotarba-Morley, Anna M.; Christie, Annalisa; Petek, Nik; Tibesasa, Ruth; Douka, Katerina (2016-05-03). "Coastal Subsistence, Maritime Trade, and the Colonization of Small Offshore Islands in Eastern African Prehistory". The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology. 11 (2): 211–237. doi:10.1080/15564894.2016.1188334. ISSN 1556-4894.

- "Historic Sites of Kilwa". World Monuments Fund. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- "The Story of Africa| BBC World Service". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- "Exotic Zanzibar and its seafood". 2011-05-21. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- Ingrams, William H. (1967), Zanzibar: Its History and Its People, Abingdon: Routledge, p. 162, ISBN 0-7146-1102-6, OCLC 186237036

- Appiah; Gates, Henry Louis Jr., eds. (1999), Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, New York: Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-00071-1, OCLC 41649745

- "dishes". www.mwambao.com. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- "Development and Promotion of Extractive Industries and Mineral Value Addition". East African Community.

- "HOME – Home". Swahililanguage.stanford.edu. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

After Arabic, Swahili is the most widely used African language but the number of its speakers is another area in which there is little agreement. The most commonly mentioned numbers are 50, 80, and 100 million people. [...] The number of its native speakers has been placed at just under 2 million.

- "History and Origin of Swahili". www.swahilihub.com. Archived from the original on 2016-06-21. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- "Swahili - Art & Life in Africa - The University of Iowa Museum of Art". africa.uima.uiowa.edu. Retrieved 2019-10-31.