Patagonia

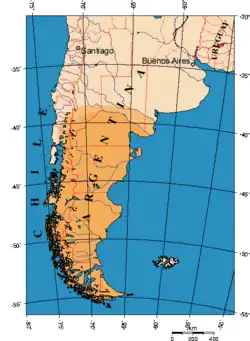

Patagonia (Spanish pronunciation: [pataˈɣonja]) is a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and glaciers in the west and deserts, tablelands and steppes to the east. Patagonia is bounded by the Pacific Ocean on the west, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, and many bodies of water that connect them, such as the Strait of Magellan, the Beagle Channel, and the Drake Passage to the south.

Patagonia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,043,076 km2 (402,734 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,999,540 |

| • Density | 1.9/km2 (5.0/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Patagonian |

| Demographics | |

| • Languages | Rioplatense Spanish, Chilean Spanish, Mapudungun, Welsh |

The Colorado and Barrancas rivers, which run from the Andes to the Atlantic, are commonly considered the northern limit of Argentine Patagonia.[1] The archipelago of Tierra del Fuego is sometimes included as part of Patagonia. Most geographers and historians locate the northern limit of Chilean Patagonia at Huincul Fault, in Araucanía Region.[2][3][4][5]

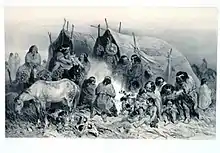

At the time of the Spanish arrival, Patagonia was inhabited by multiple indigenous tribes. In a small portion of northwestern Patagonia, indigenous peoples practiced agriculture, while in the remaining territory, peoples lived as hunter-gatherers, traveling by foot in eastern Patagonia or by dugout canoe and dalca in the fjords and channels. In colonial times indigenous peoples of northeastern Patagonia adopted a horseriding lifestyle.[6] While the interest of the Spanish Empire had been chiefly to keep other European powers away from Patagonia, independent Chile and Argentina began to colonize the territory slowly over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries. This process brought a decline of the indigenous populations, whose lives and habitats were disrupted, while at the same time thousands of Europeans, Argentines, Chilotes and mainland Chileans settled in Patagonia. Border disputes between Argentina and Chile were recurrent in the 20th century.

The contemporary economy of eastern Patagonia revolves around sheep farming and oil and gas extraction, while in western Patagonia fishing, salmon aquaculture, and tourism dominate. Culturally, Patagonia has a varied heritage, including Criollo, Mestizo, Indigenous, German, Croat, Italian, English, Scot, and Welsh influences.

Etymology and toponomies

The name Patagonia comes from the word patagón.[7] Magellan used this term in 1520 to describe the native tribes of the region, whom his expedition thought to be giants. The people he called the Patagons are now believed to have been the Tehuelche, who tended to be taller than Europeans of the time.[8][9] Argentine researcher Miguel Doura observed that the name Patagonia possibly derives from the ancient Greek region of modern Turkey called Paphlagonia, possible home of the patagon personage in the chivalric romances Primaleon printed in 1512, ten years before Magellan arrived in these southern lands. This hypothesis was published in a 2011 New Review of Spanish Philology report.[10]

There are various placenames in the Chiloé Archipelago with Chono etymologies despite the main indigenous language of the archipelago at the arrival of the Spanish being Mapudungun.[11][12] A theory postulated by chronicler José Pérez García explains this holding that the Cuncos (also known as Veliches) settled in Chiloé Island in Pre-Hispanic times as a consequence of a push from more northern Huilliches who in turn were being displaced by Mapuches.[13] While being outside traditional Huilliche territory the western Patagonian volcanoes Michimahuida, Hornopirén and Chaitén have Huilliche etymologies.[12]

In Chubut Province modern toponymy comes from the word "chupat" belonging to a transitional language between the southern and northern Tehuelche ethnic groups that were located in that region called Tewsün or Teushen. The word means transparency and is related to the clarity and purity of the river that bears that name and runs through the province. It is also related to the origin of the Welsh pronunciation of the word "chupat" which later became "Chubut". It is called "Camwy" in Patagonian Welsh. Chupat, Chubut and Camwy have the same meaning and are used to talk about the river and the province. Welsh settlers and placenames are associated with one of the projects of the country of Wales, Project Hiraeth.[14]

Due to the language, culture and location, many Patagonians do not consider themselves Latinos and proudly call themselves Patagonians instead. People from Y Wladfa, Laurie Island, the Atlantic Islands, Antarctica (including the Chilean town in Antarctica, "The Stars Village", and the Argentine civilian settlement, "Hope Base"), other non-latin speaking areas use this term as a patriotic and inclusive demonym. A Patagonian is a person that is part of the Patagonia region, language and culture. That person could be a citizen from Chilean Patagonia, Argentine Patagonia, or of native communities that existed before the land was divided by The Boundary Treaty of 1881.

Patagonia is divided between Western Patagonia (Chile) and Eastern Patagonia (Argentina) and several territories are still under dispute and claiming their rights. Mapuche people came from the Chilean Andes and voted to remain in different sides of Patagonia. Welsh settlers came from Wales and North America and voted to remain in Patagonia; when the treaty was signed, they voted for culture and administration to be apart from the country keeping the settlement, language, schools, traditions, regional dates, flag, anthems, and celebrations. Patagonians also live abroad in settlements like Saltcoats, Saskatchewan, Canada; New South Wales, Australia; South Africa; the Falkland Islands; and North America.

Population and land area

Largest cities

| City | Population | Province / Region | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuquén | 377,500 (Metropolitan area) | Neuquén Province | Argentina |

| Temuco | 200,529 (Metropolitan area) | Araucanía Region | Chile |

| Comodoro Rivadavia | 182,631 | Chubut Province | Argentina |

| Puerto Montt | 169,736 (Metropolitan area) | Los Lagos Region | Chile |

| Valdivia | 150,048 | Los Ríos Region | Chile |

| Osorno | 147,666 | Los Lagos Region | Chile |

| Punta Arenas | 123,403 | Magallanes Region | Chile |

| General Roca | 120,883 | Río Negro Province | Argentina |

| Puerto Madryn | 115,353 | Chubut Province | Argentina |

| San Carlos de Bariloche | 112,887[15] | Río Negro Province | Argentina |

| Santa Rosa | 103,241 | La Pampa Province | Argentina |

| Trelew | 97,915 | Chubut Province | Argentina |

| Río Gallegos | 95,796 | Santa Cruz Province | Argentina |

| Viedma | 80,632 | Río Negro Province | Argentina |

| Ushuaia | 77,819 | Tierra del Fuego Province | Argentina |

| Río Grande | 67,038 | Tierra del Fuego Province | Argentina |

| Coyhaique | 49,667 | Aysén Region | Chile |

| Esquel | 34,900 | Chubut Province | Argentina |

| Pucón | 28,923 | Araucanía Region | Chile |

Physical geography

Argentine Patagonia is for the most part a region of steppe-like plains, rising in a succession of 13 abrupt terraces about 100 m (330 ft) at a time, and covered with an enormous bed of shingle almost bare of vegetation.[16][17] In the hollows of the plains are ponds or lakes of fresh and brackish water. Towards Chilean territory, the shingle gives way to porphyry, granite, and basalt lavas, and animal life becomes more abundant.[16] Vegetation is more luxuriant, consisting principally of southern beech and conifers. The high rainfall against the western Andes (Wet Andes) and the low sea-surface temperatures offshore give rise to cold and humid air masses, contributing to the ice fields and glaciers, the largest ice fields in the Southern Hemisphere outside of Antarctica.[17]

Among the depressions by which the plateau is intersected transversely, the principal ones are the Gualichu, south of the Río Negro, the Maquinchao and Valcheta (through which previously flowed the waters of Nahuel Huapi Lake, which now feed the Limay River), the Senguerr (spelled Senguer on most Argentine maps and within the corresponding region), and the Deseado River. Besides these transverse depressions (some of them marking lines of ancient interoceanic communication), others were occupied by either more or less extensive lakes, such as the Yagagtoo, Musters, and Colhue Huapi, and others situated to the south of Puerto Deseado in the center of the country.[16]

Across much of Patagonia east of the Andes, volcanic eruptions have created formation of basaltic lava plateaus during the Cenozoic.[18] The plateaus are of different ages with the older –of Neogene and Paleogene age– being located at higher elevations than Pleistocene and Holocene lava plateaus and outcrops.[18]

Erosion, which is caused principally by the sudden melting and retreat of ice aided by tectonic changes, has scooped out a deep longitudinal depression, best in evidence where in contact with folded Cretaceous rocks, which are lifted up by the Cenozoic granite. It generally separates the plateau from the first lofty hills, whose ridges are generally called the pre-Cordillera. To the west of these, a similar longitudinal depression extends all along the foot of the snowy Andean Cordillera. This latter depression contains the richest, most fertile land of Patagonia.[16] Lake basins along the Cordillera were also gradually excavated by ice streams, including Lake Argentino and Lake Fagnano, as well as coastal bays such as Bahía Inútil.[17]

The establishment of dams near the Andes in Argentina in the 20th century has led to a sediment shortage along the Atlantic coast of Patagonia.[19]

Geology

The geological limit of Patagonia has been proposed to be Huincul Fault, which forms a major discontinuity. The fault truncates various structures including the Pampean orogen found further north. The ages of base rocks change abruptly across the fault.[20] Discrepancies have been mentioned among geologists on the origin of the Patagonian landmass. Víctor Ramos has proposed that the Patagonian landmass originated as an allochthonous terrane that separated from Antarctica and docked in South America 250 to 270 Mya in the Permian period.[21] A 2014 study by R.J. Pankhurst and coworkers rejects any idea of a far-traveled Patagonia, claiming it is likely of parautochtonous (nearby) origin.[22]

The Mesozoic and Cenozoic deposits have revealed a most interesting vertebrate fauna. This, together with the discovery of the perfect cranium of a turtle (chelonian) of the genus Niolamia, which is almost identical to Ninjemys oweni of the Pleistocene age in Queensland, forms an evident proof of the connection between the Australian and South American continents. The Patagonian Niolamia belongs to the Sarmienti Formation.[23] Fossils of the mid-Cretaceous Argentinosaurus, which may be the largest of all dinosaurs, have been found in Patagonia, and a model of the mid-Jurassic Piatnitzkysaurus graces the concourse of the Trelew airport (the skeleton is in the Trelew paleontological museum; the museum's staff has also announced the discovery of a species of dinosaur even bigger than Argentinosaurus[24]). Of more than paleontological interest,[25] the middle Jurassic Los Molles Formation and the still richer late Jurassic (Tithonian) and early Cretaceous (Berriasian) Vaca Muerta formation above it in the Neuquén basin are reported to contain huge hydrocarbon reserves (mostly gas in Los Molles, both gas and oil in Vaca Muerta) partly accessible through hydraulic fracturing.[26] Other specimens of the interesting fauna of Patagonia, belonging to the Middle Cenozoic, are the gigantic wingless birds, exceeding in size any hitherto known, and the singular mammal Pyrotherium, also of very large dimensions. In the Cenozoic marine formation, considerable numbers of cetaceans have been discovered.

During the Oligocene and early Miocene, large swathes of Patagonia were subject to a marine transgression, which might have temporarily linked the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, as inferred from the findings of marine invertebrate fossils of both Atlantic and Pacific affinity in La Cascada Formation.[27][28] Connection would have occurred through narrow epicontinental seaways that formed channels in a dissected topography.[27][29] The Antarctic Plate started to subduct beneath South America 14 million years ago in the Miocene, forming the Chile Triple Junction. At first, the Antarctic Plate subducted only in the southernmost tip of Patagonia, meaning that the Chile Triple Junction was located near the Strait of Magellan. As the southern part of the Nazca Plate and the Chile Rise became consumed by subduction, the more northerly regions of the Antarctic Plate began to subduct beneath Patagonia so that the Chile Triple Junction advanced to the north over time.[30] The asthenospheric window associated to the triple junction disturbed previous patterns of mantle convection beneath Patagonia inducing an uplift of c. 1 km that reversed the Miocene transgression.[29][31]

Political divisions

At a state level, Patagonia visually occupies an area within two countries: approximately 10% in Chile and approximately 90% in Argentina.[32] Both countries have organized their Patagonian territories into nonequivalent administrative subdivisions: provinces and departments in Argentina, as well as regions, provinces, and communes in Chile. As Chile is a unitary state, its first-level administrative divisions—the regions—enjoy far less autonomy than analogous Argentine provinces. Argentine provinces have elected governors and legislatures, while Chilean regions had government-appointed intendants prior to the adoption of elected governors from 2021.

The Patagonian Provinces of Argentina are Neuquén, Río Negro, Chubut, Santa Cruz, and Tierra del Fuego. The southernmost part of Buenos Aires Province can also be considered part of Patagonia.

The two Chilean regions undisputedly located entirely within Patagonia are Aysén and Magallanes. Palena Province, a part of the Los Lagos Region, is also located within Patagonia. By some definitions, Chiloé Archipelago, the rest of the Los Lagos Region, and part of the Los Ríos Region are also part of Patagonia.

Climate

Patagonia's climate is mostly cool and dry year round. The east coast is warmer than the west, especially in summer, as a branch of the southern equatorial current reaches its shores, whereas the west coast is washed by a cold current. However, winters are colder on the inland plateaus east of the slopes and further down the coast on the southeast end of the Patagonian region. For example, at Puerto Montt, on the inlet behind Chiloé Island, the mean annual temperature is 11 °C (52 °F) and the average extremes are 25.5 and −1.5 °C (77.9 and 29.3 °F), whereas at Bahía Blanca near the Atlantic coast and just outside the northern confines of Patagonia, the annual temperature is 15 °C (59 °F) and the range much greater, as temperatures above 35 °C and below −5 °C are recorded every year. At Punta Arenas, in the extreme south, the mean temperature is 6 °C (43 °F) and the average extremes are 24.5 and −2 °C (76.1 and 28.4 °F). The prevailing winds are westerly, and the westward slope has a much heavier precipitation than the eastern in a rainshadow effect;[33][17] the western islands close to Torres del Paine receive an annual precipitation of 4,000 to 7,000 mm, whilst the eastern hills are less than 800 mm and the plains may be as low as 200 mm annual precipitation.[17]

Precipitation is highly seasonal in northwestern Patagonia. For example, Villa La Angostura in Argentina, close to the border with Chile, receives up to 434 mm of rain and snow in May, 297 mm in June, and 273 in July, compared to 80 in February and 72 in March. The total for the city is 2074 mm, making it one of the rainiest in Argentina. Further west, some areas receive up to 4,000 mm and more, especially on the Chilean side. In the northeast, the seasons for rain are reversed; most rain falls from occasional summer thunderstorms but totals barely reach 500 mm in the northeast corner, and rapidly decrease to less than 300 mm. The Patagonian west coast, which belongs exclusively to Chile, has a cool oceanic climate, with summer maximum temperatures ranging from 14 °C in the south to 19 °C in the north (and nights between 5 and 11 °C) and very high precipitation, from 2,000 to more than 7,000 mm in local microclimates. Snow is uncommon at the coast in the north but happens more often in the south, and frost is usually not very intense.

Immediately east from the coast are the Andes, cut by deep fjords in the south and by deep lakes in the north, and with varying temperatures according to the altitude. The tree line ranges from close to 2,000 m on the northern side (except for the Andes in northern Neuquén in Argentina, where sunnier and dryer conditions allow trees to grow up to close to 3,000 m), and diminishes southward to only 600–800 m in Tierra del Fuego. Precipitation changes dramatically from one spot to the other and diminishes very quickly eastward. An example of this is Laguna Frías, in Argentina, which receives 4,400 mm yearly. The city of Bariloche, about 40 km further east, receives about 1,000 mm, and the airport, another 15 km east, receives less than 600 mm. The easterly slopes of the Andes are home to several Argentine cities: San Martín de los Andes, Bariloche, El Bolsón, Esquel, and El Calafate. Temperatures there are milder in the summer (in the north, between 20 and 24 °C, with cold nights between 4 and 9 °C; in the south, summers are between 16 and 20 °C, at night temperatures are similar to the north) and much colder in the winter, with frequent snowfall (although snow cover rarely lasts very long). Daytime highs range from 3 to 9 °C in the north, and from 0 to 7 °C in the south, whereas nights range from −5 to 2 °C everywhere. Cold waves can bring much colder values; a temperature of −25 °C has been recorded in Bariloche, and most places can often have temperatures between −12 and −15 °C and highs staying around 0 °C for a few days.

.jpg.webp)

Directly east of these areas, the weather becomes much harsher; precipitation drops to between 150 and 300 mm, the mountains no longer protect the cities from the wind, and temperatures become more extreme. Maquinchao is a few hundred kilometers east of Bariloche, at the same altitude on a plateau, and summer daytime temperatures are usually about 5 °C warmer, rising up to 35 °C sometimes, but winter temperatures are much more extreme: the record is −35 °C, and some nights not uncommonly reach 10 °C colder than Bariloche. The plateaus in Santa Cruz province and parts of Chubut usually have snow cover through the winter, and often experience very cold temperatures. In Chile, the city of Balmaceda is known for being situated in this region (which is otherwise almost exclusively in Argentina), and for being the coldest place in Chile, with temperatures below −20 °C every once in a while.

The northern Atlantic coast has warm summers (28 to 32 °C, but with relatively cool nights at 15 °C) and mild winters, with highs around 12 °C and lows about 2–3 °C. Occasionally, temperatures reach −10 or 40 °C, and rainfall is very scarce. The weather only gets a bit colder further south in Chubut, and the city of Comodoro Rivadavia has summer temperatures of 24 to 28 °C, nights of 12 to 16 °C, and winters with days around 10 °C and nights around 3 °C, and less than 250 mm of rain. However, a drastic drop occurs as one moves south to Santa Cruz; Rio Gallegos, in the south of the province, has summer temps of 17 to 21 °C, (nights between 6 and 10 °C) and winter temperatures of 2 to 6 °C, with nights between −5 and 0 °C, despite being right on the coast. Snowfall is common despite the dryness, and temperatures are known to fall to under −18 °C and to remain below freezing for several days in a row. Rio Gallegos is also among the windiest places on Earth, with winds reaching 100 km/h occasionally.

Tierra del Fuego is extremely wet in the west, relatively damp in the south, and dry in the north and east. Summers are cool (13 to 18 °C in the north, 12 to 16 °C in the south, with nights generally between 3 and 8 °C), cloudy in the south, and very windy. Winters are dark and cold, but without the extreme temperatures in the south and west (Ushuaia rarely reaches −10 °C, but hovers around 0 °C for several months, and snow can be heavy). In the east and north, winters are much more severe, with cold snaps bringing temperatures down to −20 °C all the way to the Rio Grande on the Atlantic coast. Snow can fall even in the summer in most areas, as well.

Fauna

The guanaco (Lama guanicoe), South American cougar (Puma concolor concolor), the Patagonian fox (Lycalopex griseus), Patagonian hog-nosed skunk (Conepatus humboldtii), and Magellanic tuco-tuco (Ctenomys magellanicus; a subterranean rodent) are the most characteristic mammals of the Patagonian plains.[33] The Patagonian steppe is one of the last strongholds of the guanaco and Darwin's rheas (Rhea pennata),[34] which had been hunted for their skins by the Tehuelches, on foot using boleadoras, before the diffusion of firearms and horses;[35] they were formerly the chief means of subsistence for the natives, who hunted them on horseback with dogs and bolas. Vizcachas (Lagidum spp.) and the Patagonian mara[34] (Dolichotis patagonum) are also characteristic of the steppe and the pampas to the north.

Bird life is often abundant. The crested caracara (Caracara plancus) is one of the characteristic objects of a Patagonian landscape; the presence of austral parakeets (Enicognathus ferrugineus) as far south as the shores of the strait attracted the attention of the earlier navigators, and green-backed firecrowns (Sephanoides sephaniodes), a species of hummingbird, may be seen flying amid the snowfall. One of the largest birds in the world, the Andean condor (Vultur gryphus) can be seen in Patagonia.[36] Of the many kinds of waterfowl[34] the Chilean flamingo (Phoenicopterus chilensis), the upland goose (Chloephaga picta), and in the strait, the remarkable steamer ducks are found.[33]

Signature marine fauna include the southern right whale, the Magellanic penguin (Spheniscus magellanicus), the killer whale, and elephant seals. The Valdés Peninsula is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, designated for its global significance as a site for the conservation of marine mammals.[37]

The Patagonian freshwater fish fauna is relatively restricted compared to other similar Southern Hemisphere regions. The Argentine part is home to a total of 29 freshwater fish species, 18 of which are native.[38] The introduced are several species of trout, common carp, and various species that originated in more northerly parts of South America. The natives are osmeriforms (Aplochiton and Galaxias), temperate perches (Percichthys), catfish (Diplomystes, Hatcheria and Trichomycterus), Neotropical silversides (Odontesthes) and characiforms (Astyanax, Cheirodon, Gymnocharacinus, and Oligosarcus).[38] Other Patagonian freshwater fauna include the highly unusual aeglid crustaceans.[39]

History

Pre-Columbian Patagonia (10,000 BC – AD 1520)

Human habitation of the region dates back thousands of years,[40] with some early archaeological findings in the area dated to at least the 13th millennium BC, although later dates around the 10th millennium BC are more securely recognized. Evidence exists of human activity at Monte Verde in Llanquihue Province, Chile, dated to around 12,500 BC.[17] The glacial-period ice fields and subsequent large meltwater streams would have made settlement difficult at that time.

The region seems to have been inhabited continuously since 10,000 BC, by various cultures and alternating waves of migration, the details of which are as yet poorly understood. Several sites have been excavated, notably caves such as Cueva del Milodon[41] in Última Esperanza in southern Patagonia, and Tres Arroyos on Tierra del Fuego, that support this date.[17] Hearths, stone scrapers, and animal remains dated to 9400–9200 BC have been found east of the Andes.[17]

The Cueva de las Manos is a famous site in Santa Cruz, Argentina. This cave at the foot of a cliff is covered in wall paintings, particularly the negative images of hundreds of hands, believed to date from around 8000 BC.[17]

Based on artifacts found in the region, apparently hunting of guanaco, and to a lesser extent rhea (ñandú), were the primary food sources of tribes living on the eastern plains.[17] Whether the megafauna of Patagonia, including the ground sloth and horse, were extinct in the area before the arrival of humans is unclear, although this is now the more widely accepted account. It is also not clear if domestic dogs were part of early human activity. Bolas are commonly found and were used to catch guanaco and rhea.[17] A maritime tradition existed along the Pacific coast,[42] whose latest exponents were the Yaghan (Yámana) to the south of Tierra del Fuego, the Kaweshqar between Taitao Peninsula and Tierra del Fuego, and the Chono people in the Chonos Archipelago. The Selk'nam, Haush, and Tehuelche are generally thought to be culturally and linguistically related peoples physically distinct from the sea-faring peoples.[43]

It is possible that Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego was connected to the mainland in the Early Holocene (c. 9000 years BP) much in the same way that Riesco Island was back then.[44] A Selk'nam tradition recorded by the Salesian missionary Giuseppe María Beauvoir relate that the Selk'nam arrived in Tierra del Fuego by land, and that the Selk'nam were later unable to return north as the sea had flooded their crossing.[45]

Agriculture was practised in Pre-Hispanic Argentina as far south as southern Mendoza Province.[46] Agriculture was at times practised beyond this limit in nearby areas of Patagonia but populations reverted at times to non-agricultural lifestyles.[46] By the time of the Spanish arrival to the area (1550s) there is no record of agriculture being practised in northern Patagonia.[46] The extensive Patagonian grasslands and an associated abundance of guanaco game may have contributed for the indigenous populations to favour a hunter-gathered lifestyle.[46]

The indigenous peoples of the region included the Tehuelches, whose numbers and society were reduced to near extinction not long after the first contacts with Europeans. Tehuelches included the Gununa'kena to the north, Mecharnuekenk in south-central Patagonia, and the Aonikenk or Southern Tehuelche in the far south, north of the Magellan strait. On Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, the Selk'nam (Ona) and Haush (Manek'enk) lived in the north and southeast, respectively. In the archipelagos to the south of Tierra del Fuego were Yámana, with the Kawéskar (Alakaluf) in the coastal areas and islands in western Tierra del Fuego and the southwest of the mainland.[17] In the Patagonian archipelagoes north of Taitao Peninsula lived the Chonos. These groups were encountered in the first periods of European contact with different lifestyles, body decoration, and language, although it is unclear when this configuration emerged.

Towards the end of the 16th century, Mapuche-speaking agriculturalists penetrated the western Andes and from there across into the eastern plains and down to the far south. Through confrontation and technological ability, they came to dominate the other peoples of the region in a short period of time, and are the principal indigenous community today.[17]

Early European exploration (1520–1669)

Navigators such as Gonçalo Coelho and Amerigo Vespucci possibly had reached the area (his own account of 1502 has it that they reached the latitude 52°S), but Vespucci's failure to accurately describe the main geographical features of the region such as the Río de la Plata casts doubts on whether they really did so.

The first or more detailed description of part of the coastline of Patagonia is possibly mentioned in a Portuguese voyage in 1511–1512, traditionally attributed to captain Diogo Ribeiro, who after his death was replaced by Estevão de Frois, and was guided by the pilot and cosmographer João de Lisboa). The explorers, after reaching Rio de la Plata (which they would explore on the return voyage, contacting the Charrúa and other peoples) eventually reached San Matias Gulf, at 42°S. The expedition reported that after going south of the 40th parallel, they found a "land" or a "point extending into the sea", and further south, a gulf. The expedition is said to have rounded the gulf for nearly 300 km (186 mi) and sighted the continent on the southern side of the gulf.[47][48]

The Atlantic coast of Patagonia was first fully explored in 1520 by the Spanish expedition led by Ferdinand Magellan, who on his passage along the coast named many of its more striking features – San Matías Gulf, Cape of 11,000 Virgins (now simply Cape Virgenes), and others.[33] Magellan's fleet spent a difficult winter at what he named Puerto San Julián before resuming its voyage further south on 21 August 1520. During this time, it encountered the local inhabitants, likely to be Tehuelche people, described by his reporter, Antonio Pigafetta, as giants called Patagons.[49]

The territory became the Spanish colony of the Governorate of New Léon, granted in 1529 to Governor Simón de Alcazaba y Sotomayor, part of the Governorates of the Spanish Empire of the Americas. The territory was redefined in 1534 and consisted of the southernmost part of the South American continent and the islands towards Antarctica.

Rodrigo de Isla, sent inland in 1535 from San Matías by Simón de Alcazaba y Sotomayor (on whom western Patagonia had been conferred by Charles I of Spain, is presumed to have been the first European to have traversed the great Patagonian plain. If the men under his charge had not mutinied, he might have crossed the Andes to reach the Pacific coast.

Pedro de Mendoza, on whom the country was next bestowed, founded Buenos Aires, but did not venture south. Alonso de Camargo (1539), Juan Ladrilleros (1557), and Hurtado de Mendoza (1558) helped to make known the Pacific coasts, and while Sir Francis Drake's voyage in 1577 down the Atlantic coast, through the Strait of Magellan and northward along the Pacific coast, was memorable,[33] yet the descriptions of the geography of Patagonia owe much more to the Spanish explorer Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa (1579–1580), who, devoting himself especially to the south-west region, made careful and accurate surveys. The settlements that he founded at Nombre de Jesús and San Felipe was neglected by the Spanish government, the latter being abandoned before Thomas Cavendish visited it in 1587 during his circumnavigation, and so desolate that he called it Port Famine.[33] After the discovery of the route around Cape Horn, the Spanish Crown lost interest in southern Patagonia until the 18th century, when the coastal settlements Carmen de Patagones, San José, Puerto Deseado, and Nueva Colonia Floridablanca were established, although it maintained its claim of a de jure sovereignty over the area.

In 1669, the district around Puerto Deseado was explored by John Davis and was claimed in 1670 by Sir John Narborough for King Charles II of England, but the English made no attempt to establish settlements or explore the interior.

Patagonian giants: early European perceptions

The first European explorers of Patagonia observed that the indigenous people in the region were taller than the average Europeans of the time, prompting some of them to believe that Patagonians were giants.

According to Antonio Pigafetta,[7] one of the Magellan expedition's few survivors and its published chronicler, Magellan bestowed the name Patagão (or Patagón) on the inhabitants they encountered there, and the name "Patagonia" for the region. Although Pigafetta's account does not describe how this name came about, subsequent popular interpretations gave credence to a derivation meaning "land of the big feet". However, this etymology is questionable. The term is most likely derived from an actual character name, "Patagón", a savage creature confronted by Primaleón of Greece, the hero in the homonymous Spanish chivalry novel (or knight-errantry tale) by Francisco Vázquez.[50] This book, published in 1512, was the sequel of the romance Palmerín de Oliva;it was much in vogue at the time, and a favorite reading of Magellan. Magellan's perception of the natives, dressed in skins, and eating raw meat, clearly recalled the uncivilized Patagón in Vázquez's book. Novelist and travel writer Bruce Chatwin suggests etymological roots of both Patagon and Patagonia in his book, In Patagonia,[51] noting the similarity between "Patagon" and the Greek word παταγος, which means "a roaring" or "gnashing of teeth" (in his chronicle, Pigafetta describes the Patagonians as "roaring like bulls").

The main interest in the region sparked by Pigafetta's account came from his reports of their meeting with the local inhabitants, whom they claimed to measure some 9 to 12 feet in height – "so tall that we reached only to his waist" – hence the later idea that Patagonia meant "big feet". This supposed race of Patagonian giants or Patagones entered into the common European perception of this then little-known and distant area, to be further fueled by subsequent reports of other expeditions and famous travelers such as Sir Francis Drake, which seemed to confirm these accounts. Early charts of the New World sometimes added the legend regio gigantum ("region of the giants") to the Patagonian area. By 1611, the Patagonian god Setebos (Settaboth in Pigafetta) was familiar to the hearers of The Tempest.[33]

The concept and general belief persisted for a further 250 years and was to be sensationally reignited in 1767 when an "official" (but anonymous) account was published of Commodore John Byron's recent voyage of global circumnavigation in HMS Dolphin. Byron and crew had spent some time along the coast, and the publication (Voyage Round the World in His Majesty's Ship the Dolphin) seemed to give proof positive of their existence; the publication became an overnight bestseller, thousands of extra copies were to be sold to a willing public, and other prior accounts of the region were hastily republished (even those in which giant-like folk were not mentioned at all).

However, the Patagonian giant frenzy died down substantially only a few years later, when some more sober and analytical accounts were published. In 1773, John Hawkesworth published on behalf of the Admiralty a compendium of noted English southern-hemisphere explorers' journals, including that of James Cook and John Byron. In this publication, drawn from their official logs, the people Byron's expedition had encountered clearly were no taller than 6-foot-6-inch (1.98 m), very tall but by no means giants. Interest soon subsided, although awareness of and belief in the concept persisted in some quarters even into the 20th century.[52]

Spanish outposts

The Spanish failure at colonizing the Strait of Magellan made Chiloé Archipelago assume the role of protecting the area of western Patagonia from foreign intrusions.[53] Valdivia, reestablished in 1645, and Chiloé acted as sentries, being hubs where the Spanish collected information and rumors from all over Patagonia.[54]

As a result of the corsair and pirate menace, Spanish authorities ordered the depopulation of the Guaitecas Archipelago to deprive enemies of any eventual support from native populations.[11] This then led to the transfer of the majority of the indigenous Chono population to the Chiloé Archipelago in the north while some Chonos moved south of Taitao Peninsula effectively depopulating the territory in the 18th century.[11]

The publication of Thomas Falkner's book A Description of Patagonia and the Adjacent Parts of South America in England fuelled speculations in Spain about renewed British interest in Patagonia. In response an order from the King of Spain was issued to settle the eastern coast of Patagonia.[55] This led to the brief existence of colonies at the Gulf of San Jorge (1778–1779) and San Julián (1780–1783) and the more longlasting colony of Carmen de Patagones.[55]

Scientific exploration (1764–1842)

In the second half of the 18th century, European knowledge of Patagonia was further augmented by the voyages of the previously mentioned John Byron (1764–1765), Samuel Wallis (1766, in the same HMS Dolphin which Byron had earlier sailed in) and Louis Antoine de Bougainville (1766). Thomas Falkner, a Jesuit who resided near forty years in those parts, published his Description of Patagonia (Hereford, 1774); Francisco Viedma founded El Carmen, nowadays Carmen de Patagones and Antonio settled the area of San Julian Bay, where he founded the colony of Floridablanca and advanced inland to the Andes (1782). Basilio Villarino ascended the Rio Negro (1782).[33]

_p131_UNA_FIESTA_EN_CALEUFU.JPG.webp)

Two hydrographic surveys of the coasts were of first-rate importance; the first expedition (1826–1830) included HMS Adventure and HMS Beagle under Phillip Parker King, and the second (1832–1836) was the voyage of the Beagle under Robert FitzRoy. The latter expedition is particularly noted for the participation of Charles Darwin, who spent considerable time investigating various areas of Patagonia onshore, including long rides with gauchos in Río Negro, and who joined FitzRoy in a 200 mi (320 km) expedition taking ships' boats up the course of the Santa Cruz River.[33]

Spanish American independence wars

During the independence wars rumours about the imminent arrival of Spanish troops to Patagonia, either from Peru or Chiloé, were common among indigenous peoples of the Pampas and northern Patagonia.[56] In 1820 Chilean patriot leader José Miguel Carrera allied with the indigenous Ranquel people of the Pampas in order to fight the rival patriots in Buenos Aires.[56] José Miguel Carrera ultimately planned to cross the Andes into Chile and oust his rivals in Chile.

The last royalist armed group in what is today Argentina and Chile, the Pincheira brothers, moved from the vicinities of Chillán across the Andes into northern Patagonia as patriots consolidated control of Chile. The Pincheira brothers was an outlaw gang made of Europeans Spanish, American Spanish, Mestizos and local indigenous peoples.[57] This group was able to move to Patagonia thanks to its alliance with two indigenous tribes, the Ranqueles and the Boroanos.[57][56] In the interior of Patagonia, far from the de facto territory of Chile and the United Provinces, the Pincheira brothers established permanent encampment with thousands of settlers.[57] From their bases the Pincheiras led numerous raids into the countryside of the newly established republics.[56]

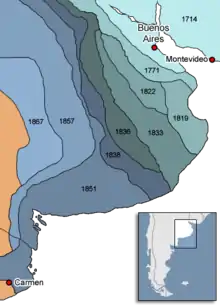

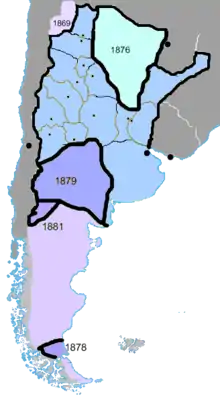

Chilean and Argentine colonization (1843–1902)

In the early 19th century, the araucanization of the natives of northern Patagonia intensified, and many Mapuches migrated to Patagonia to live as nomads that raised cattle or pillaged the Argentine countryside. The cattle stolen in the incursions (malones) were later taken to Chile through the mountain passes and traded for goods, especially alcoholic beverages. The main trail for this trade was called Camino de los chilenos and runs a length around 1000 km from the Buenos Aires Province to the mountain passes of Neuquén Province. The lonco Calfucurá crossed the Andes from Chile to the pampas around 1830, after a call from the governor of Buenos Aires, Juan Manuel de Rosas, to fight the Boroano people. In 1859, he attacked Bahía Blanca in Argentina with 3,000 warriors. As in the case of Calfucura, many other bands of Mapuches got involved in the internal conflicts of Argentina until Conquest of the Desert. To counter the cattle raids, a trench called the Zanja de Alsina was built by Argentina in the pampas in the 1870s.

In the mid-19th century, the newly independent nations of Argentina and Chile began an aggressive phase of expansion into the south, increasing confrontation with the Indigenous peoples of the region. In 1860, French adventurer Orelie-Antoine de Tounens proclaimed himself king of the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia of the Mapuche.

Following the last instructions of Bernardo O'Higgins, the Chilean president Manuel Bulnes sent an expedition to the Strait of Magellan and founded Fuerte Bulnes in 1843. Five years later, the Chilean government moved the main settlement to the current location of Punta Arenas, the oldest permanent settlement in Southern Patagonia. The creation of Punta Arenas was instrumental in making Chile's claim of the Strait of Magellan permanent. In the 1860s, sheep from the Falkland Islands were introduced to the lands around the Straits of Magellan, and throughout the 19th century, sheepfarming grew to be the most important economic sector in southern Patagonia.

George Chaworth Musters in 1869 wandered in company with a band of Tehuelches through the whole length of the country from the strait to the Manzaneros in the northwest, and collected a great deal of information about the people and their mode of life.[33][63]

Conquest of the Desert and the 1881 treaty

Argentine authorities worried that the strong connections araucanized tribes had with Chile would allegedly give Chile certain influence over the pampas.[64] Argentine authorities feared that in an eventual war with Chile over Patagonia, the natives would side with the Chileans and the war would be brought to the vicinity of Buenos Aires.[64]

The decision to plan and execute the Conquest of the Desert was probably catalyzed by the 1872 attack of Cufulcurá and his 6,000 followers on the cities of General Alvear, Veinticinco de Mayo, and Nueve de Julio, where 300 criollos were killed, and 200,000 heads of cattle taken. In the 1870s, the Conquest of the Desert was a controversial campaign by the Argentine government, executed mainly by General Julio Argentino Roca, to subdue or, some claim, to exterminate the native peoples of the south.

In 1885, a mining expeditionary party under the Romanian adventurer Julius Popper landed in southern Patagonia in search of gold, which they found after traveling southwards towards the lands of Tierra del Fuego. This led to the further opening up of the area to prospectors. European missionaries and settlers arrived throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, notably the Welsh settlement of the Chubut Valley. Numerous Croatians also settled in Patagonia.[65]

During the first years of the 20th century, the border between the two nations in Patagonia was established by the mediation of the British crown. Numerous modifications have been made since then, the last conflict having been resolved in 1994 by an arbitration tribunal constituted in Rio de Janeiro. It granted Argentina sovereignty over the Southern Patagonia Icefield, Cerro Fitz Roy, and Laguna del Desierto.[66][67]

Until 1902, a large proportion of Patagonia's population were natives of Chiloé Archipelago (Chilotes), who worked as peons in large livestock-farming estancias. Because they were manual laborers, their social status was below that of the gauchos and the Argentine, Chilean, and European landowners and administrators.

Before and after 1902, when the boundaries were drawn, Argentina expelled many Chilotes from their territory, as they feared that having a large Chilean population in Argentina could pose a risk to their future control. These workers founded the first inland Chilean settlement in what is now the Aysén Region;[68][69] Balmaceda. Lacking good grasslands on the forest-covered Chilean side, the immigrants burned down the forest, setting fires that could last more than two years.[69]

Economy

The area's principal economic activities have been mining, whaling, livestock (notably sheep throughout) agriculture (wheat and fruit production near the Andes towards the north), and oil after its discovery near Comodoro Rivadavia in 1907.[70]

Energy production is also a crucial part of the local economy. Railways were planned to cover continental Argentine Patagonia to serve the oil, mining, agricultural, and energy industries, and a line was built connecting San Carlos de Bariloche to Buenos Aires. Portions of other lines were built to the south, but the only lines still in use are La Trochita in Esquel, the Train of the End of the World in Ushuaia, both heritage lines,[71] and a short run Tren Histórico de Bariloche to Perito Moreno.

In the western forest-covered Patagonian Andes and archipelagoes, wood logging has historically been an important part of the economy; it impelled the colonization of the areas of the Nahuel Huapi and Lácar lakes in Argentina and Guaitecas Archipelago in Chile.

Livestock

Sheep farming introduced in the late 19th century has been a principal economic activity. After reaching its heights during the First World War, the decline in world wool prices affected sheep farming in Argentina. Nowadays, about half of Argentina's 15 million sheep are in Patagonia, a percentage that is growing as sheep farming disappears in the pampas to the north. Chubut (mainly Merino) is the top wool producer with Santa Cruz (Corriedale and some Merino) second. Sheep farming revived in 2002 with the devaluation of the peso and firmer global demand for wool (led by China and the EU). Still, little investment occurs in new abattoirs (mainly in Comodoro Rivadavia, Trelew, and Rio Gallegos), and often phytosanitary restrictions reduce the export of sheep meat. Extensive valleys in the Cordilleran Range have provided sufficient grazing lands, and the low humidity and weather of the southern region make raising Merino and Corriedale sheep common.

Livestock also includes small numbers of cattle, and in lesser numbers, pigs and horses. Sheep farming provides a small but important number of jobs for rural areas with little other employment.

Tourism

In the second half of the 20th century, tourism became an ever more important part of Patagonia's economy. Originally a remote backpacking destination, the region has attracted increasing numbers of upmarket visitors, cruise passengers rounding Cape Horn or visiting Antarctica, and adventure and activity holiday-makers. Principal tourist attractions include the Perito Moreno glacier, the Valdés Peninsula, the Argentine Lake District and Ushuaia and Tierra del Fuego (the city is also a jumping-off place for travel to Antarctica, bringing in still more visitors). Tourism has created new markets locally and for export for traditional crafts such as Mapuche handicrafts, guanaco textiles, and confectionery and preserves.[70]

A spin-off from increased tourism has been the buying of often enormous tracts of land by foreigners, often as a prestige purchase rather than for agriculture. Buyers have included Sylvester Stallone, Ted Turner, and Christopher Lambert, and most notably Luciano Benetton, Patagonia's largest landowner.[70] His "Compañia de Tierras Sud" has brought new techniques to the ailing sheep-rearing industry and sponsored museums and community facilities, but has been controversial particularly for its treatment of local Mapuche communities.[72]

Energy

Due to its sparse rainfall in agricultural areas, Argentine Patagonia already has numerous dams for irrigation, some of which are also used for hydropower. The Limay River is used to generate hydroelectricity at five dams built on its course: Alicurá, Piedra del Águila, Pichi Picún Leufú, El Chocón, and Arroyito. Together with the Cerros Colorados Complex on the Neuquén River, they contribute more than one-quarter of the total hydroelectric generation in the country.

Patagonia has always been Argentina's main area, and Chile's only area, of conventional oil and gas production. Oil and gas have played an important role in the rise of Neuquén-Cipolleti as Patagonia's most populous urban area, and in the growth of Comodoro Rivadavia, Punta Arenas, and Rio Grande, as well. The development of the Neuquén basin's enormous unconventional oil and gas reserves through hydraulic fracturing has just begun, but the YPF-Chevron Loma Campana field in the Vaca Muerta formation is already the world's largest producing shale oil field outside North America according to former YPF CEO Miguel Gallucio.

Patagonia's notorious winds have already made the area Argentina's main source of wind power, and plans have been made for major increases in wind power generation. Coal is mined in the Rio Turbio area and used for electricity generation.

Cuisine

Argentine Patagonian cuisine is largely the same as the cuisine of Buenos Aires – grilled meats and pasta – with extensive[73] use of local ingredients and less use of those products that have to be imported into the region. Lamb is considered the traditional Patagonian meat, grilled for several hours over an open fire. Some guide books have reported that game meats, especially guanaco and introduced deer and boar, are popular in restaurant cuisine. However, since guanaco is a protected animal in both Chile and Argentina, it is unlikely to appear commonly as restaurant fare. Trout and centolla (king crab) are also common, though overfishing of centolla has made it increasingly scarce. In the area around Bariloche, a noted Alpine cuisine tradition remains, with chocolate bars and even fondue restaurants, and tea rooms are a feature of the Welsh communities in Gaiman and Trevelin, as well as in the mountains.[70] Since the mid-1990s, some success with winemaking has occurred in Argentine Patagonia, especially in Neuquén.

Foreign land buyers issue

Foreign investors, including Italian multinational Benetton Group, Ted Turner, Joseph Lewis[74] and the conservationist Douglas Tompkins, own major land areas. This situation has caused several conflicts with local inhabitants and the governments of Chile and Argentina, for example, the opposition by Douglas Tompkins to the planned route for Carretera Austral in Pumalín Park. A scandal is also brewing about two properties owned by Ted Turner: the estancia La Primavera, located inside Nahuel Huapi National Park, and the estancia Collón Cura.[74] Benetton has faced criticism from Mapuche organizations, including Mapuche International Link, over its purchase of traditional Mapuche lands in Patagonia. The Curiñanco-Nahuelquir family was evicted from their land in 2002 following Benetton's claim to it, but the land was restored in 2007.[75][76]

In fiction

In Jules Verne's 1867–1868 novel Les Enfants du capitaine Grant (The Children of Captain Grant, alternatively 'In Search of the Castaways'), the search for Captain Grant gets underway when the Duncan, a vessel in the ownership of Lord Glenarvan, is taken on a journey to the western shore of South America's Patagonian region where the crew is split up, and Lord Glenarvan proceeds to lead a party eastwards across Patagonia to eventually reunite with the Duncan (which had doubled the Cape in the meanwhile).

The future history depicted in Olaf Stapledon's 1930 novel Last and First Men includes a far future time in which Patagonia becomes the center of a new world civilization while Europe and North America are reduced to the status of backward poverty-stricken areas.

In William Goldman’s 1987 movie The Princess Bride, Westley, the current inheritor of the moniker "the Dread Pirate Roberts", states that the "real" (original) Dread Pirate Roberts is retired and "living like a king in Patagonia".

See also

- Apostolic Prefecture of Southern Patagonia

- Apostolic Vicariate of Northern Patagonia

- Beagle conflict

- Domuyo

- Francisco Moreno Museum of Patagonia

- Lago Puelo National Park

- Lanín National Park

- Lanín Volcano

- List of deserts by area

- Los Alerces National Park

- Los Glaciares National Park

- Mount Hudson

- Nahuel Huapi National Park

- Patagonian Expedition Race

- Patagonian Ice Sheet

- Southern Cone

- Y Wladfa

References

- The Late Cenozoic of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego Volumen 11 de Developments in quaternary science, pág. 13. Autor: Jorge Rabassa. Editor: Jorge Rabassa. Editor: Elsevier, 2008. ISBN 0-444-52954-3, 9780444529541

- Manuel Enrique Schilling; Richard WalterCarlson; AndrésTassara; Rommulo Vieira Conceição; Gustavo Walter Bertotto; Manuel Vásquez; Daniel Muñoz; Tiago Jalowitzki; Fernanda Gervasoni; Diego Morata (2017). "The origin of Patagonia revealed by Re-Os systematics of mantle xenoliths." Precambrian Research, volumen 294: 15–32.

- Zunino, H.; Matossian, B.; Hidalgo, R. (2012). "Poblamiento y desarrollo de enclaves turísticos en la Norpatagonia chileno-argentina. Migración y frontera en un espacio binacional." (Population and development of tourist enclaves in the Chilean-Argentine Norpatagonia. Migration and the border in a binational space), Revista de Geografía Norte Grande, 53: 137–158.

- Zunino, M.; Espinoza, L.; Vallejos-Romero A. (2016) Los migrantes por estilo de vida como agentes de transformación en la Norpatagonia chilena, Revista de Estudios Sociales, 55 (2016): 163–176.

- Ciudadanía, territorio y desarrollo endógeno: resistencias y mediaciones de las políticas locales en las encrucijadas del neoliberalismo. Pág. 205. Autores: Rubén Zárate, Liliana Artesi, Oscar Madoery. Editor: Editorial Biblos, 2007. ISBN 950-786-616-7, 9789507866166

- Cayuqueo, Pedro (2020). Historia secreta mapuche 2. Santiago de Chile: Catalonia. pp. 34–37. ISBN 978-956-324-783-1.

- Antonio Pigafetta, Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo, 1524: "Il capitano generale nominò questi popoli Patagoni." A Brief Declaration of the Vyage abowte the Worlde by Antonie Pygafetta Vincentine, Rycharde Eden, The Decades of the Newe Worlde or West India, London, William Powell, 1555. The original word was likely in Magellan's native Portuguese (patagão) or the Spanish of his men (patagón). It was later interpreted later as "bigfoot", but the etymology refers to a literary character in a Spanish novel of the early 16th century:

Patagon, said to be engendred by a beast in the woods, being the strangest, most misshapen, and counterfeit creature in the world. He hath good understanding, is amorous of women, and keepeth company with one of whom, it is said, he was engendred. He hath the face of a Dogge, great ears, which hang down upon his shoulders, his teeth sharp and big, standing out of his mouth very much: his feet are like a Harts, and he runneth wondrous lightly. Such as have seen him, tell marvelous matters of him, because he chaseth ordinarily among the mountains, with two Lyons in a chain like a lease, and a bow in his hand.Anthony Munday, The Famous and Renowned Historie of Primaleon of Greece, 1619, cap.XXXIII: "How Primaleon... found the Grand Patagon".

- Fondebrider, Jorge (2003). "Chapter 1 – Ámbitos y voces". Versiones de la Patagonia (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Buenos Aires, Argentina: Emecé Editores S.A. p. 29. ISBN 978-950-04-2498-1.

- Robert Silverberg (2011). "The Strange Case of the Patagonian Giants" (PDF). Asimov's Science Fiction.

To the voyagers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when the average height of an adult European male was just over five feet [1.55 meters], the Patagonians surely must have looked very large, as, to any child, all adults seem colossal. Then, too, an element of understandable human exaggeration must have entered these accounts of men who had traveled so far and endured so much, and the natural wish not to be outdone by one's predecessors helped to produce these repeated fantasies of Goliaths ten feet tall or even more.

- Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica 59 (1): pp. 37–78. 2011. ISSN 0185-0121

- Ibar Bruce, Jorge (1960). "Ensayo sobre los indios Chonos e interpretación de sus toponimías". Anales de la Universidad de Chile (in Spanish). 117: 61–70.

- Latorre, Guillermo (1998). "Sustrato y superestrato multilingües en la toponimia del extremo sur de Chile" [Multilingual substratum and superstratum in the toponymy of the south of Chile]. Estudios Filológicos (in Spanish). 33: 55–67.

- Alcamán, Eugenio (1997). "Los mapuche-huilliche del Futahuillimapu septentrional: Expansión colonial, guerras internas y alianzas políticas (1750-1792)" (PDF). Revista de Historia Indígena (in Spanish) (2): 29–76. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Stefani, Catalina Lidia (2020). "Una mirada historiográfica sobre la construcción de la toponimia departamental del Territorio Nacional del Chubut". Revista TEFROS. 18 (2): 139–151.

- "Aseguran que en Bariloche viven 30 mil personas más que las censadas ::: ANGOSTURA DIGITAL - DIARIO DE VILLA LA ANGOSTURA Y REGION DE LOS LAGOS - PATAGONIA ARGENTINA - Actualidad, cuentos, efemerides, turismo, nieve, pesca, montañismo, cursos, historia, reportajes". Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 899.

- Patagonia: Natural History, Prehistory and Ethnography at the Uttermost End of the Earth, C. McEwan, L.A. and A. Prieto (eds), Princeton University Press with British Museum Press, 1997. ISBN 0-691-05849-0

- Mazzoni, Elizabeth; Rabassa, Jorge (2010). "Inventario y clasificación de manifestaciones basálticas de Patagonia mediante imágenes satelitales y SIG, Provincia de Santa Cruz" [Inventory and classification of basaltic occurrences of Patagonia based on satellite images and G.I.S, province of Santa Cruz] (PDF). Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina (in Spanish). 66 (4): 608–618.

- Isla, Federico Ignacio; Isla, Manuel Fermín (2022). "Geological Changes in Coastal Areas of Patagonia, Argentina, and Chile". In Helbling, E. Walter; Narvarte, Maite A.; González, Raul A.; Villafañe, Virginia E. (eds.). Global Change in Atlantic Coastal Patagonian Ecosystems. Natural and Social Sciences of Patagonia. Springer. pp. 73–89. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-86676-1_4. ISBN 978-3-030-86675-4.

- Ramos, V.A.; Riccardi, A.C.; Rolleri, E.O. (2004). "Límites naturales del norte de la Patagonia". Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina (in Spanish). 59 (4).

- Jaramillo, Jessica (6 April 2014). "Entrevista al Dr. Víctor Alberto Ramos, Premio México Ciencia y Tecnología 2013" (in Spanish).

Incluso ahora continúa la discusión sobre el origen de la Patagonia, la cual lleva más de veinte años sin lograr un consenso entre la comunidad científica. Lo que propone el grupo de investigación en el que trabaja el geólogo es que la Patagonia se originó en el continente Antártico, para después separarse y formar parte de Gondwana, alrededor de 250 a 270 millones de años.

- Pankhurst, R.J.; Rapela, C.W.; López de Luchi, M.G.; Rapalini, A.E.; Fanning, C.M.; Galindo, C. (2014). "The Gondwana connections of northern Patagonia" (PDF). Journal of the Geological Society, London. 171 (3): 313–328. Bibcode:2014JGSoc.171..313P. doi:10.1144/jgs2013-081. S2CID 53687880.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 900.

- Morgan, James (17 May 2014). "BBC News - 'Biggest dinosaur ever' discovered". BBC News. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- Though not without it where the formations surface; see Chacaicosaurus and Mollesaurus from the Los Molles, and Caypullisaurus, Cricosaurus, Geosaurus, Herbstosaurus, and Wenupteryx from the Vaca Muerta.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration, Technically Recoverable Shale Oil and Shale Gas Resources: An Assessment of 137 Shale Formations in 41 Countries Outside the United States, June 2013, pp. V-1 through V-13. According to the same study, the Austral (Argentine name) or Magallanes (Chilean name) basin under the southern Patagonian mainland and Tierra del Fuego may also have massive hydrocarbon reserves in early Cretaceous shales; see pp. V-23 and VII-17 in particular. On 21 May 2014, YPF also announced the first oil and gas discovery in the D-129 shale formation of the Golfo San Jorge area in Chubut, and on 14 August 2014, the first shale oil discovery in yet another Cretaceous formation in the Neuquén basin, the Valanginian/Hauterivian Agrio formation; see "YPF confirmó la presencia de hidrocarburos no convencionales en Chubut". Archived from the original on 26 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014., and "Galuccio inauguró el Espacio de la Energía de YPF en Tecnópolis". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Encinas, Alfonso; Pérez, Felipe; Nielsen, Sven; Finger, Kenneth L.; Valencia, Victor; Duhart, Paul (2014). "Geochronologic and paleontologic evidence for a Pacific–Atlantic connection during the late Oligocene–early Miocene in the Patagonian Andes (43–44°S)". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 55: 1–18. Bibcode:2014JSAES..55....1E. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2014.06.008. hdl:10533/130517.

- Nielsen, S.N. (2005). "Cenozoic Strombidae, Aporrhaidae, and Struthiolariidae (Gastropoda, Stromboidea) from Chile: their significance to biogeography of faunas and climate of the south-east Pacific". Journal of Paleontology. 79 (6): 1120–1130. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2005)079[1120:csaasg]2.0.co;2. S2CID 130207579.

- Guillame, Benjamin; Martinod, Joseph; Husson, Laurent; Roddaz, Martin; Riquelme, Rodrigo (2009). "Neogene uplift of central eastern Patagonia: Dynamic response to active spreading ridge subduction?" (PDF). Tectonics. 28 (2): TC2009. Bibcode:2009Tecto..28.2009G. doi:10.1029/2008tc002324.

- Cande, S.C.; Leslie, R.B. (1986). "Late Cenozoic Tectonics of the Southern Chile Trench". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 91 (B1): 471–496. Bibcode:1986JGR....91..471C. doi:10.1029/jb091ib01p00471.

- Guillaume, Benjamin; Gautheron, Cécile; Simon-Labric, Thibaud; Martinod, Joseph; Roddaz, Martin; Douville, Eric (2013). "Dynamic topography control on Patagonian relief evolution as inferred from low temperature thermochronology". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 364: 157–167. Bibcode:2013E&PSL.364..157G. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2012.12.036.

- "Patagonia Map: Main regions and areas of Patagonia".

- Chisholm 1911, p. 901.

- WCS. "Patagonia and Southern Andean Steppe, Argentina". Saving Wild Places. Wildlife Conservation Society. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- Rhys, David Hall (1976). A geographic study of the Welsh colonization in Chubut, Patagonia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Xerox University Microfilms. pp. 84–88.

- WCS. "Andean condor". Saving wildlife. World Conservation Society. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- UNESCO. "Península Valdés". UNESCO World Heritage Center. UNESCO. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- Baigun, C.; Ferriz, R.A. (2003). "Distribution patterns of freshwater fishes in Patagonia (Argentina)". Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 3 (2): 151–159. doi:10.1078/1439-6092-00075.

- Christopher C. Tudge (2003). "Endemic and enigmatic: the reproductive biology of Aegla (Crustacea: Anomura: Aeglidae) with observations on sperm structure". Memoirs of Museum Victoria. 60 (1): 63–70. doi:10.24199/j.mmv.2003.60.9.

- SCHLOSSBERG, TATIANA (17 June 2016). "12,000 Years Ago, Humans and Climate Change Made a Deadly Team". NYT. NYC. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- C. Michael Hogan (2008) Cueva del Milodon, The Megalithic Portal, ed. A. Burnham

- Mostny 1983, p. 34.

- Chapman, Anne; Hester, Thomas R. (1973). "New data on the archaeology of the Haush: Tierra del Fuego". Journal de la Société des Américaniste. 62: 185–208. doi:10.3406/jsa.1973.2088.

- Mostny 1983, p. 21.

- "Selk'nam". La enciclopedia de ciencias y tecnologías en Argentina (in Spanish). 1 December 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Neme, Gustavo; Gil, Adolfo; Salgán, Laura; Giardina, Miguel; Otaola, Clara; Pompei, María de la Paz; Peralta, Eva; Sugrañes, Nuria; Franchetti, Fernando Ricardo; Abonna, Cinthia (2022). "Una Aproximación Biogeográfica a los Límites de la Agricultura en el Norte de Patagonia, Argentina" [A Biogeographic Approach to Farming Limits in Northern Patagonia, Argentina] (PDF). Chungara (in Spanish). 54 (3): 397–418.

- Oskar Hermann Khristian Spate. The Spanish Lake. Canberra: ANU E Press, 2004. p. 37.

- Newen Zeytung auss Presillg Landt (in ancient German and Portuguese) Newen Zeytung auss Presillg Landt

- Laurence Bergreen (14 October 2003). Over the Edge of the World. Harper Perennial, 2003. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-06-621173-2.

- Ulijaszek, Stanley J.; Johnston, Francis E.; Preece, M. A., eds. (1998). "Patagonian Giants: Myths and Possibilities". The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Growth and Development. Cambridge University Press. p. 380.

- Chatwin, Bruce. In Patagonia (1977). ch. 49

- Carolyne Ryan. "European Travel Writings and the Patagonian giants". Lawrence University. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- Urbina C., M. Ximena (2013). "Expediciones a las costas de la Patagonia Occidental en el periodo colonial". Magallania (in Spanish). 41 (2): 51–84. doi:10.4067/S0718-22442013000200002.

- Urbina C., María Ximena (2017). "La expedición de John Narborough a Chile, 1670: Defensa de Valdivia, rumeros de indios, informaciones de los prisioneros y la creencia en la Ciudad de los Césares" [John Narborough expedition to Chile, 1670: Defense of Valdivia, indian rumors, information on prisoners, and the belief in the City of the Césares]. Magallania. 45 (2): 11–36. doi:10.4067/S0718-22442017000200011.

- Williams (1975), p. 17–18.

- Ratto, Silvia (2008). "¿Revolución en las pampas? Diplomacia y malones entre indígenas de pampa y patagonia". In Fradkin, Raúl O. (ed.). ¿Y el Pueblo dónde está? Contribuciones para una historia popular de la revolución de independencia en el Río de la Plata (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Prometeo Libros. pp. 241–246. ISBN 978-987-574-248-2.

- Manara, Carla G. (2010). "Movilización en las fronteras. Los Pincheira y el última intento de reconquista hispana en el sur Americano (1818-1832)" (PDF). Revista Sociedad de Paisajes Áridos y Semiáridos (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional de Río Cuarto. II (II): 39–60.

- Dalmacio Vélez Sarsfield (1853). Discusión de los títulos del Gobierno de Chile a las tierras del Estrecho de Magallanes. Imprenta Argentina.

- Eyzaguirre, Jaime (1967). Breve historia de las fronteras de Chile. Editorial Universitaria.

- Lagos Carmona, Guillermo (1985). Los Títulos Históricos: Historia de Las Fronteras de Chile. Andrés Bello.

- Amunátegui, Miguel Luis (1985). Títulos de la República de Chile a la soberanía i dominio de la Estremidad.

- Morla Vicuña, Carlos (1903). Estudio histórico sobre el descubrimiento y conquista de la Patagonia y de la Tierra del Fuego. Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus.

- Dickenson, John. "Musters, George Chaworth". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19679. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Perry, Richard O. (1980). "Argentina and Chile: The Struggle For Patagonia 1843–1881". The Americas. 36 (3): 347–363. doi:10.2307/981291. JSTOR 981291. S2CID 147607097.

- Bilić, Danira (5 May 2008). "Vučetić's time and the Croatian community in Argentina". Croatian Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011.

- Rosa, Carlos Leonardo de la (1 January 1998). Acuerdo sobre los hielos continentales: razones para su aprobación. Ediciones Jurídicas Cuyo. ISBN 9789509099678.

- es:Disputa de la laguna del Desierto

- "Coihaique – Ciudades y Pueblos del sur de Chile". Turistel.cl. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Luis Otero, La Huella del Fuego: Historia de los bosques y cambios en el paisaje del sur de Chile (Valdivia, Editorial Pehuen)

- Time Out Patagonia, Cathy Runciman (ed), Penguin Books, 2002. ISBN 0-14-101240-4

- History of the Old Patagonian Express Archived 27 August 2005 at the Wayback Machine, La Trochita, accessed 2006-08-11

- 'The Invisible Colors of Benetton', Mapuche International Link, accessed 2006-08-11

- "Travel to Patagonia: Must-Try Argentina Foods". Say Hueque. 4 May 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Rivers of bloodfrom Patagonia-argentina.com".

- "Recovered Mapuche territory in Patagonia: Benetton vs. Mapuche". MAPU Association. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- "Exploring Patagonia in Argentina and Chile".

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Patagonia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 899–901.

- Mostny, Grete (1983) [1981]. Prehistoria de Chile (in Spanish) (6th ed.). Santiago de Chile: Editorial Universitaria.

- Williams, Glyn (1975). The Desert and the Dream. University of Wales Press. ISBN 0708305792.

Further reading

- The Last Cowboys at the End of the World: The Story of the Gauchos of Patagonia, Nick Reding, 2002. ISBN 0-609-81004-9

- The Old Patagonian Express, Paul Theroux, 1979.

- In Patagonia, Bruce Chatwin, 1977 and 1988. ISBN 0-14-243719-0

- Patagonia Express, Luis Sepulveda, 2004. ISBN 978-8483835784

- Patagonia: A Cultural History, Chris Moss, 2008. ISBN 978-1-904955-38-2

- Patagonia: A Forgotten Land: From Magellan to Peron, C. A. Brebbia, 2006. ISBN 978-1-84564-061-3

- The Wild Shores of Patagonia: The Valdés Peninsula & Punta Tombo, Jasmine Rossi, 2000. ISBN 0-8109-4352-2

- Luciana Vismara, Maurizio OM Ongaro, PATAGONIA – E-BOOK W/ UNPUBLISHED FOTOS, MAPS, TEXTS (Formato Kindle – 6 November 2011) – eBook Kindle

- Adventures in Patagonia: a missionary's exploring trip, Titus Coan, 1880. Library of Congress Control Number 03009975. A list of writings relating to Patagonia, 320–21.

- Idle Days in Patagonia by William Henry Hudson, Chapman and Hall Ltd, London, 1893

External links

- Gallery of photos from Patagonia – Jakub Polomski Photography

- Photos from Chilean Patagonia (2008–2011) by Jorge Uzon

- Patagonia Nature Photo Gallery: Landscapes, flora and fauna from Argentina and Chile

- Patagon Journal, magazine about Patagonia

- Aborigines of Patagonia

- 'Backpacking Patagonia' - series of articles about solo hiking in Patagonia

.svg.png.webp)