Sustainability measurement

Sustainability measurement is a set of frameworks or indicators to measure how sustainable something is. This includes processes, products, services and businesses. Sustainability is difficult to quantify. It may even be impossible to measure.[1] To measure sustainability, the indicators consider environmental, social and economic domains. The metrics are still evolving. They include indicators, benchmarks and audits. They include sustainability standards and certification systems like Fairtrade and Organic. They also involve indices and accounting. And they can include assessment, appraisal[2] and other reporting systems. These metrics are used over a wide range of spatial and temporal scales.[3][1] Sustainability measures include corporate sustainability reporting, Triple Bottom Line accounting. They include estimates of the quality of sustainability governance for individual countries. These use the Environmental Sustainability Index and Environmental Performance Index. Some methods let us track sustainable development.[4][5] These include the UN Human Development Index and ecological footprints.

Two related concepts to understand if the mode of life of humanity is sustainable, are planetary boundaries[6] and ecological footprint.[7] If the boundaries are not crossed and the ecological footprint is not exceeding the carrying capacity of the biosphere, the mode of life is regarded as sustainable.

A set of well defined and harmonized indicators can help to make sustainability tangible. Those indicators are expected to be identified and adjusted through empirical observations (trial and error).[8] The most common critiques are related to issues like data quality, comparability, objective function and the necessary resources.[9] However a more general criticism is coming from the project management community: "How can a sustainable development be achieved at global level if we cannot monitor it in any single project?".[10]

Sustainability need and framework

Sustainable development has become the primary yardstick of improvement for industries and is being integrated into effective government and business strategies. The needs for sustainability measurement include improvement in the operations, benchmarking performances, tracking progress, and evaluating process, among others.[11] For the purposes of building sustainability indicators, frameworks can be developed and the steps are as follows:[12]

- Defining the system- A proper and definite system is defined. A proper system boundary is drawn for further analysis.

- Elements of the system- The whole input, output of materials, emissions, energy and other auxiliary elements are properly analysed. The working conditions, process parameters and characteristics are defined in this step.

- Indicators selection- The indicators is selected of which measurement has to be done. This forms the metric for this system whose analysis is done in the further steps.

- Assessment and Measurement- Proper assessing tools are used and tests or experiments are performed for the pre-defined indicators to give a value for the indicators measurement.

- Analysis and reviewing the results- Once the results have been obtained, proper analysis and interpretation is done and tools are used to improve and revise the processes present in the system.

Sustainability indicators and their function

The principal objective of sustainability indicators is to inform public policy-making as part of the process of sustainability governance.[13] Sustainability indicators can provide information on any aspect of the interplay between the environment and socio-economic activities.[14] Building strategic indicator sets generally deals with just a few simple questions: what is happening? (descriptive indicators), does it matter and are we reaching targets? (performance indicators), are we improving? (efficiency indicators), are measures working? (policy effectiveness indicators), and are we generally better off? (total welfare indicators).

The International Institute for Sustainable Development and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development established the Committee on Sustainability Assessment (COSA) in 2006 to evaluate sustainability initiatives operating in agriculture and develop indicators for their measurable social, economic and environmental objectives.[15]

One popular general framework used by The European Environment Agency uses a slight modification of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development DPSIR system.[16] This breaks up environmental impact into five stages. Social and economic developments (consumption and production) (D)rive or initiate environmental (P)ressures which, in turn, produces a change in the (S)tate of the environment which leads to (I)mpacts of various kinds. Societal (R)esponses (policy guided by sustainability indicators) can be introduced at any stage of this sequence of events.

Politics

A study concluded that social indicators and, therefore, sustainable development indicators, are scientific constructs whose principal objective is to inform public policy-making.[17] The International Institute for Sustainable Development has similarly developed a political policy framework, linked to a sustainability index for establishing measurable entities and metrics. The framework consists of six core areas:

- International trade and investment

- Economic policy

- Climate change and energy

- Measurement and assessment

- Natural resource management

- Communication technologies.

The United Nations Global Compact Cities Programme has defined sustainable political development in a way that broadens the usual definition beyond states and governance. The political is defined as the domain of practices and meanings associated with basic issues of social power as they pertain to the organisation, authorisation, legitimation and regulation of a social life held in common. This definition is in accord with the view that political change is important for responding to economic, ecological and cultural challenges. It also means that the politics of economic change can be addressed. They have listed seven subdomains of the domain of politics:[18]

- Organization and governance

- Law and justice

- Communication and critique

- Representation and negotiation

- Security and accord

- Dialogue and reconciliation

- Ethics and accountability

Metrics at the global scale

There are numerous indicators which could be used as basis for sustainability measurement. Few commonly used indicators are:

Environmental sustainability indicators:[19]

- Global warming potential

- Acidification potential

- Ozone depletion potential

- Aerosol optical depth

- Eutrophication potential

- Ionization radiation potential

- Photochemical ozone potential

- Waste treatment

- Freshwater use

- Energy resources use

- Level of Biodiversity[20]

- Gross domestic product

- Trade balance

- Local government income

- Profit, value and tax

- Investments

Social indicators:[22]

- Employment generated

- Equity

- Health and safety

- Education

- Housing/living conditions

- Community cohesion

- Social security

Due to the large numbers of various indicators that could be used for sustainability measurement, proper assessment and monitoring is required.[22] In order to organize the chaos and disorder in selecting the metrics, specific organizations have been set up which groups the metrics under different categories and defines proper methodology to implement it for measurement. They provide modelling techniques and indexes to compare the measurement and have methods to convert the scientific measurement results into easy to understand terms.[23]

United Nations indicators

The United Nations has developed extensive sustainability measurement tools in relation to sustainable development [24] as well as a System of Integrated Environmental and Economic Accounting.[25]

The UN Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD) has published a list of 140 indicators which covers environmental, social, economical and institutional aspects of sustainable development.[26]

Benchmarks, indicators, indexes, auditing etc.

In the last couple of decades, there has arisen a crowded toolbox of quantitative methods used to assess sustainability — including measures of resource use like life cycle assessment, measures of consumption like the ecological footprint and measurements of quality of environmental governance like the Environmental Performance Index. The following is a list of quantitative "tools" used by sustainability scientists - the different categories are for convenience only as defining criteria will intergrade. It would be too difficult to list all those methods available at different levels of the organization so those listed here are at the global level only.

- A benchmark is a point of reference for a measurement. Once a benchmark is established it is possible to assess trends and measure progress. Baseline global data on a range of sustainability parameters is available in the list of global sustainability statistics.

- A sustainability index is an aggregate sustainability indicator that combines multiple sources of data. There is a Consultative Group on Sustainable Development Indices[27]

|

- Many environmental problems ultimately relate to the human effect on those global biogeochemical cycles that are critical to life. Over the last decade monitoring these cycles have become a more urgent target for research:

- Sustainability auditing and reporting are used to evaluate the sustainability performance of a company, organization, or other entity using various performance indicators.[31] Popular auditing procedures available at the global level include:

- ISO 14000

- ISO 14031

- The Natural Step

- Triple Bottom Line Accounting

- input-output analysis can be used for any level of organization with a financial budget. It relates environmental impact to expenditure by calculating the resource intensity of goods and services.

- Reporting

- Global Reporting Initiative modelling and monitoring procedures.[32][33][34] Many of these are currently in their developing phase.

- State of the Environment reporting provides general background information on the environment and is progressively including more indicators.

- European sustainability [35]

- Accounting

- Some accounting methods attempt to include environmental costs rather than treating them as externalities

- Green accounting

- Sustainable value

- Sustainability economics [36]

Life cycle analysis

A life cycle analysis is often conducted when assessing the sustainability of a product or prototype.[37] The decision to choose materials is heavily weighted on its longevity, renewability, and efficiency. These factors ensure that researchers are conscious of community values that align with positive environmental, social, and economic impacts.[37]

Resource metrics

Part of this process can relate to resource use such as energy accounting or to economic metrics or price system values as compared to non-market economics potential, for understanding resource use.[38]

An important task for resource theory (energy economics) is to develop methods to optimize resource conversion processes.[39] These systems are described and analyzed by means of the methods of mathematics and the natural sciences.[40] Human factors, however, have dominated the development of our perspective of the relationship between nature and society since at least the Industrial Revolution, and in particular, have influenced how we describe and measure the economic impacts of changes in resource quality. A balanced view of these issues requires an understanding of the physical framework in which all human ideas, institutions, and aspirations must operate.[41]

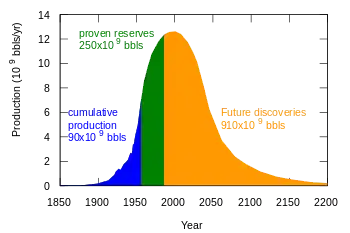

Energy returned on energy invested

When oil production first began in the mid-nineteenth century, the largest oil fields recovered fifty barrels of oil for every barrel used in the extraction, transportation, and refining. This ratio is often referred to as the Energy Return on Energy Investment (EROI or EROEI). Currently, between one and five barrels of oil are recovered for each barrel-equivalent of energy used in the recovery process.[42] As the EROEI drops to one, or equivalently the net energy gain falls to zero, the oil production is no longer a net energy source.[43] This happens long before the resource is physically exhausted.

Note that it is important to understand the distinction between a barrel of oil, which is a measure of oil, and a barrel of oil equivalent (BOE), which is a measure of energy. Many sources of energy, such as fission, solar, wind, and coal, are not subject to the same near-term supply restrictions that oil is. Accordingly, even an oil source with an EROEI of 0.5 can be usefully exploited if the energy required to produce that oil comes from a cheap and plentiful energy source. Availability of cheap, but hard to transport, natural gas in some oil fields has led to using natural gas to fuel enhanced oil recovery. Similarly, natural gas in huge amounts is used to power most Athabasca Tar Sands plants. Cheap natural gas has also led to ethanol fuel produced with a net EROEI of less than 1, although figures in this area are controversial because methods to measure EROEI are in debate.

Growth-based economic models

Insofar as economic growth is driven by oil consumption growth, post-peak societies must adapt. M. King Hubbert believed:[44]

Our principal constraints are cultural. During the last two centuries we have known nothing but exponential growth and in parallel we have evolved what amounts to an exponential-growth culture, a culture so heavily dependent upon the continuance of exponential growth for its stability that it is incapable of reckoning with problems of nongrowth.

Some economists describe the problem as uneconomic growth or a false economy. At the political right, Fred Ikle has warned about "conservatives addicted to the Utopia of Perpetual Growth".[45] Brief oil interruptions in 1973 and 1979 markedly slowed – but did not stop – the growth of world GDP.[46]

Between 1950 and 1984, as the Green Revolution transformed agriculture around the globe, world grain production increased by 250%. The energy for the Green Revolution was provided by fossil fuels in the form of fertilizers (natural gas), pesticides (oil), and hydrocarbon fueled irrigation.[47]

David Pimentel, professor of ecology and agriculture at Cornell University, and Mario Giampietro, senior researcher at the National Research Institute on Food and Nutrition (INRAN), place in their study Food, Land, Population and the U.S. Economy the maximum U.S. population for a sustainable economy at 200 million. To achieve a sustainable economy world population will have to be reduced by two-thirds, says the study.[48] Without population reduction, this study predicts an agricultural crisis beginning in 2020, becoming critical c. 2050. The peaking of global oil along with the decline in regional natural gas production may precipitate this agricultural crisis sooner than generally expected. Dale Allen Pfeiffer claims that coming decades could see spiraling food prices without relief and massive starvation on a global level such as never experienced before.[49][50]

Hubbert peaks

There is an active debate about most suitable sustainability indicator's use and by adopting a thermodynamic approach through the concept of "exergy" and Hubbert peaks, it is possible to incorporate all into a single measure of resource depletion.The exergy analysis of minerals could constitute a universal and transparent tool for the management of the earth's physical stock.[51][22]

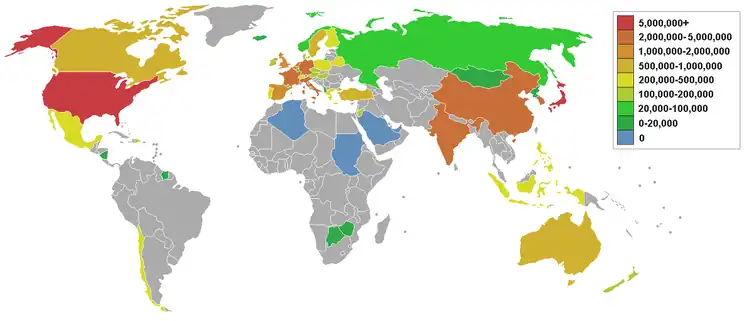

Hubbert peak can be used as a metric for sustainability and depletion of non-renewable resources. It can be used as reference for many metrics for non-renewable resources such as:[52]

- Stagnating supplies

- Rising prices

- Individual country peaks

- Decreasing discoveries

- Finding and development costs

- Spare capacity

- Export capabilities of producing countries

- System inertia and timing

- Reserves-to-production ratio

- Past history of depletion and optimism

Although Hubbert peak theory receives most attention in relation to peak oil production, it has also been applied to other natural resources.

Natural gas

Doug Reynolds predicted in 2005 that the North American peak would occur in 2007.[53] Bentley (p. 189) predicted a world "decline in conventional gas production from about 2020".[54]

Coal

Peak coal is significantly further out than peak oil, but we can observe the example of anthracite in the US, a high grade coal whose production peaked in the 1920s. Anthracite was studied by Hubbert, and matches a curve closely.[55] Pennsylvania's coal production also matches Hubbert's curve closely, but this does not mean that coal in Pennsylvania is exhausted—far from it. If production in Pennsylvania returned at its all-time high, there are reserves for 190 years. Hubbert had recoverable coal reserves worldwide at 2500 × 109 metric tons and peaking around 2150(depending on usage).

More recent estimates suggest an earlier peak. Coal: Resources and Future Production (PDF 630KB [56]), published on April 5, 2007 by the Energy Watch Group (EWG), which reports to the German Parliament, found that global coal production could peak in as few as 15 years.[57] Reporting on this Richard Heinberg also notes that the date of peak annual energetic extraction from coal will likely come earlier than the date of peak in quantity of coal (tons per year) extracted as the most energy-dense types of coal have been mined most extensively.[58] A second study, The Future of Coal by B. Kavalov and S. D. Peteves of the Institute for Energy (IFE), prepared for European Commission Joint Research Centre, reaches similar conclusions and states that ""coal might not be so abundant, widely available and reliable as an energy source in the future".[57]

Work by David Rutledge of Caltech predicts that the total of world coal production will amount to only about 450 gigatonnes.[59] This implies that coal is running out faster than usually assumed.

Finally, insofar as global peak oil and peak in natural gas are expected anywhere from imminently to within decades at most, any increase in coal production (mining) per annum to compensate for declines in oil or NG production, would necessarily translate to an earlier date of peak as compared with peak coal under a scenario in which annual production remains constant.

Fissionable materials

In a paper in 1956,[60] after a review of US fissionable reserves, Hubbert notes of nuclear power:

There is promise, however, provided mankind can solve its international problems and not destroy itself with nuclear weapons, and provided world population (which is now expanding at such a rate as to double in less than a century) can somehow be brought under control, that we may at last have found an energy supply adequate for our needs for at least the next few centuries of the "foreseeable future."

Technologies such as the thorium fuel cycle, reprocessing and fast breeders can, in theory, considerably extend the life of uranium reserves. Roscoe Bartlett claims [61]

Our current throwaway nuclear cycle uses up the world reserve of low-cost uranium in about 20 years.

Caltech physics professor David Goodstein has stated[62] that

... you would have to build 10,000 of the largest power plants that are feasible by engineering standards in order to replace the 10 terawatts of fossil fuel we're burning today ... that's a staggering amount and if you did that, the known reserves of uranium would last for 10 to 20 years at that burn rate. So, it's at best a bridging technology ... You can use the rest of the uranium to breed plutonium 239 then we'd have at least 100 times as much fuel to use. But that means you're making plutonium, which is an extremely dangerous thing to do in the dangerous world that we live in.

Metals

Hubbert applied his theory to "rock containing an abnormally high concentration of a given metal"[63] and reasoned that the peak production for metals such as copper, tin, lead, zinc and others would occur in the time frame of decades and iron in the time frame of two centuries like coal. The price of copper rose 500% between 2003 and 2007[64] was by some attributed to peak copper.[65][66] Copper prices later fell, along with many other commodities and stock prices, as demand shrank from fear of a global recession.[67] Lithium availability is a concern for a fleet of Li-ion battery using cars but a paper published in 1996 estimated that world reserves are adequate for at least 50 years.[68] A similar prediction [69] for platinum use in fuel cells notes that the metal could be easily recycled.

Phosphorus

Phosphorus supplies are essential to farming and depletion of reserves is estimated at somewhere from 60 to 130 years.[70] Individual countries supplies vary widely; without a recycling initiative America's supply [71] is estimated around 30 years.[72] Phosphorus supplies affect total agricultural output which in turn limits alternative fuels such as biodiesel and ethanol.

Peak water

Hubbert's original analysis did not apply to renewable resources. However over-exploitation often results in a Hubbert peak nonetheless. A modified Hubbert curve applies to any resource that can be harvested faster than it can be replaced.[73]

For example, a reserve such as the Ogallala Aquifer can be mined at a rate that far exceeds replenishment. This turns much of the world's underground water [74] and lakes [75] into finite resources with peak usage debates similar to oil. These debates usually center around agriculture and suburban water usage but generation of electricity [76] from nuclear energy or coal and tar sands mining mentioned above is also water resource intensive. The term fossil water is sometimes used to describe aquifers whose water is not being recharged.

Renewable resources

- Fisheries: At least one researcher has attempted to perform Hubbert linearization (Hubbert curve) on the whaling industry, as well as charting the transparently dependent price of caviar on sturgeon depletion.[77] Another example is the cod of the North Sea.[78] The comparison of the cases of fisheries and of mineral extraction tells us that the human pressure on the environment is causing a wide range of resources to go through a depletion cycle which follows a Hubbert curve.

Sustainability gaps

Sustainability measurements and indicators are part of an ever-evolving and changing process and has various gaps to be filled to achieve an integrated framework and model. The following are some of the breaks in continuity:

- Global indicators- Due to differences in social, economical, and environmental conditions of countries, each country has its own indicators and indexes to measure sustainability, which can lead to improper and varying interpretation at the global level. Hence, there common indexes and measuring parameters would allow comparisons among countries.[79][80] In agriculture, comparable indicators are already in use. Coffee and cocoa studies in twelve countries[81] using common indicators are among the first to report insights from comparing across countries.

- Policymaking- After the indicators are defined and analysis is done for the measurements from the indicators, proper policymaking methodology can be set up to improve the results achieved. Policymaking would implement changes in the particular inventory list used for measuring, which could lead to better results.[82][83]

- Development of individual indicators- Value-based indicators can be developed to measure the efforts by every human being part of the ecosystem. This can affect policymaking, as policy is most effective when there is public participation.[79]

- Data collection- Due to a number of factors including inappropriate methodology applied to data collection, dynamics of change in data, lack of adequate time and improper framework in analysis of data, measurements can quickly become outdated, inaccurate, and unpresentable. Data collections built up from the grass-roots level allow context-appropriate frameworks and regulations associated with it. A hierarchy of data collection starts from local zones to state level, to national level and finally contributing to the global level measurements. Data collected can be made easy to understand so that it could be correctly interpreted and presented through graphs, charts, and analysis bars.[84][82][79]

- Integration across academic disciplines- Sustainability involves the whole ecosystem and is intended to have a holistic approach. For this purpose measurements intend to involve data and knowledge from all academic backgrounds. Moreover, these disciplines and insights are intended to align with the societal actions.[79][82][80][83][84]

See also

References

- Bell, Simon and Morse, Stephen 2008. Sustainability Indicators. Measuring the Immeasurable? 2nd edn. London: Earthscan. ISBN 978-1-84407-299-6.

- Dalal-Clayton, Barry and Sadler, Barry 2009. Sustainability Appraisal: A Sourcebook and Reference Guide to International Experience. London: Earthscan. ISBN 978-1-84407-357-3.

- Hak, T. et al. 2007. Sustainability Indicators, SCOPE 67. Island Press, London. Archived 2011-12-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Wackernagel, Mathis; Lin, David; Evans, Mikel; Hanscom, Laurel; Raven, Peter (2019). "Defying the Footprint Oracle: Implications of Country Resource Trends". Sustainability. 11 (7): 2164. doi:10.3390/su11072164.

- "Sustainable Development visualized". Sustainability concepts. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- Steffen, Will (13 Feb 2015). "Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet". Science. 347 (6223): 1259855. doi:10.1126/science.1259855. hdl:1885/13126. PMID 25592418. S2CID 206561765.

- "Ecological Footprints". Sustainability concepts. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Reed, Mark S. (2006). "An adaptive learning process for developing and applying sustainability indicators with local communities" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 59 (4): 406–418. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.11.008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- "Annette Lang, Ist Nachhaltigkeit messbar?, Uni Hannover, 2003" (PDF) (in German). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Do global targets matter?, The Environment Times, Poverty Times #4, UNEP/GRID-Arendal, 2010". Grida.no. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- Martins, António A.; Mata, Teresa M.; Costa, Carlos A. V.; Sikdar, Subhas K. (2007-05-01). "Framework for Sustainability Metrics". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 46 (10): 2962–2973. doi:10.1021/ie060692l. ISSN 0888-5885.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-06-19. Retrieved 2019-03-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Boulanger, P. M. (2008-11-26). "Sustainable development indicators: a scientific challenge, a democratic issue". S.A.P.I.EN.S. 1 (1). Archived from the original on 2011-01-09. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- Hak, T., Moldan, B. & Dahl, A.L. 2007. SCOPE 67. Sustainability indicators. Island Press, London.

- Giovannucci D, Potts J (2007). The COSA Project (PDF) (Report). International Institute for Sustainable Development. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-01-02. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- Stanners, D. et al. 2007. Frameworks for environmental assessment and indicators at the EEA. In: Hak, T., Moldan, B. & Dahl, A.L. 2007. SCOPE 67. Sustainability indicators. Island Press, London.

- Paul-Marie Boulanger (2008). "Sustainable development indicators: a scientific challenge, a democratic issue". S.A.P.I.EN.S. 1 (1). Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- http://citiesprogramme.com/archives/resource/circles-of-sustainability-urban-profile-process Archived 12 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine Liam Magee; Andy Scerri; Paul James; James A. Thom; Lin Padgham; Sarah Hickmott; Hepu Deng; Felicity Cahill (2013). "Reframing social sustainability reporting: Towards an engaged approach". Environment, Development and Sustainability. 15: 225–243. doi:10.1007/s10668-012-9384-2. S2CID 153452740.

- Dong, Yan; Hauschild, Michael Z. (2017). "Indicators for Environmental Sustainability". Procedia CIRP. 61: 697–702. doi:10.1016/j.procir.2016.11.173.

- Bell, Simon; Morse, Stephen (2012-05-04). Sustainability Indicators: Measuring the Immeasurable?. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-55602-9.

- Tisdell, Clem (May 1996). "Economic indicators to assess the sustainability of conservation farming projects: An evaluation". Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 57 (2–3): 117–131. doi:10.1016/0167-8809(96)01017-1.

- Labuschagne, Carin; Brent, Alan C.; van Erck, Ron P.G. (March 2005). "Assessing the sustainability performances of industries". Journal of Cleaner Production. 13 (4): 373–385. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2003.10.007. hdl:2263/4325.

- "Indicators and a Monitoring Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals .:. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform". sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Archived from the original on 2019-08-16. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- Archived 2009-02-05 at the Wayback Machine United Nations sustainable development indicators

- Archived 2014-03-31 at the Wayback Machine, International Standard Industrial Classification UN System of Integrated Environmental and Economic Accounting

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-09-22. Retrieved 2019-03-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Consultative Group on Sustainable Development Indices". International Institute for Sustainable Development. Archived from the original on 2019-10-12. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- "Green Score City Index". GreenScore.eco. Retrieved 2022-03-21. The Green Score City Index: development and application at a municipal scale

- "SGI – Sustainable Governance Indicators 2011". Sgi-network.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- Archived 2005-12-16 at the Wayback Machine Sullivan, C.A. et al. (eds) 2003. The water poverty index: development and application at the community scale. Natural Resources Forum 27: 189-199.

- Hill, J. 1992. Towards Good Environmental Practice. The Institute of Business Ethics, London.

- "Global Reporting Initiative". Global Reporting Initiative. Archived from the original on 2008-06-16. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- "Global Reporting Initiative Guidelines 2002" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-17. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- "International Corporate Sustainability Reporting". Archived from the original on 2007-11-21. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- Eurostat. (2007). "Measuring progress towards a more sustainable Europe. 2007 monitoring report of the EU sustainable development strategy." Retrieved on 2009-04-14.

- Archived 2008-02-05 at the Wayback Machine|Publications on sustainability measurement used in sustainability economics

- Mestre, Ana; Cooper, Tim (2017). "Circular Product Design. A Multiple Loops Life Cycle Design Approach for the Circular Economy". Design Journal. 20: S1620–S1635. doi:10.1080/14606925.2017.1352686.

- "Net energy analysis". Eoearth.org. 2010-07-23. Archived from the original on 2013-04-29. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- "Environmental Decision Making, Science, and Technology". Telstar.ote.cmu.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-01-05. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- "Exergy - A Useful Concept.Intro". Exergy.se. Archived from the original on 2012-07-16. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- "Energy and economic myths (historical)". Eoearth.org. Archived from the original on 2013-06-06. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- Tripathi, Vinay S.; Brandt, Adam R. (2017-02-08). "Estimating decades-long trends in petroleum field energy return on investment (EROI) with an engineering-based model". PLOS ONE. 12 (2): e0171083. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1271083T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171083. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5298284. PMID 28178318.

- Michaux, Simon. "Appendix D -ERoEI Comparison of Energy Resources". Academia. Archived from the original on 2019-12-12. Retrieved 2019-02-25.

- "Exponential Growth as a Transient Phenomenon in Human History". Hubbertpeak.com. Archived from the original on 2019-06-29. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- "Our Perpetual Growth Utopia". Dieoff.org. Archived from the original on 2019-04-28. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - How peak oil could lead to starvation Archived 2007-08-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Taggart, Adam (2003-10-02). "Eating Fossil Fuels". EnergyBulletin.net. Archived from the original on 2007-06-11. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- Peak Oil: the threat to our food security Archived July 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- The Oil Drum: Europe. "Agriculture Meets Peak Oil". Europe.theoildrum.com. Archived from the original on 2015-12-29. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- Valero, Alicia; Valero, Antonio; Mudd, Gavin M (2009). Exergy – A Useful Indicator for the Sustainability of Mineral Resources and Mining. Proceedings of SDIMI Conference. Gold Coast, QLD. pp. 329–38. ISBN 978-1-921522-01-7.

- Brecha, Robert (12 February 2013). "Ten Reasons to Take Peak Oil Seriously". Sustainability. 5 (2): 664–694. doi:10.3390/su5020664.

- White, Bill (December 17, 2005). "State's consultant says nation is primed for using Alaska gas". Anchorage Daily News. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009.

- Bentley, R.W. (2002). "Viewpoint - Global oil & gas depletion: an overview" (PDF). Energy Policy. 30 (3): 189–205. doi:10.1016/S0301-4215(01)00144-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-27. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- GEO 3005: Earth Resources Archived July 25, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Startseite" (PDF). Energy Watch Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- Hamilton, Rosie (2007-05-21). "Peak coal: sooner than you think". Energybulletin.net. Archived from the original on 2008-05-22. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- "Museletter". Richard Heinberg. December 2009. Archived from the original on 2012-08-06. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- "Coal: Bleak outlook for the black stuff", by David Strahan, New Scientist, Jan. 19, 2008, pp. 38-41.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-27. Retrieved 2014-11-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-25. Retrieved 2006-11-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Jones, Tony (23 November 2004). "Professor Goodstein discusses lowering oil reserves". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 2013-05-09. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- "Exponential Growth as a Transient Phenomenon in Human History". Hubbertpeak.com. Archived from the original on 2013-07-12. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/mcs-2008-coppe.pdf Copper Statistics and Information, 2007 Archived 2017-11-23 at the Wayback Machine. USGS

- Andrew Leonard (2006-03-02). "Peak copper?". Salon - How the World Works. Archived from the original on 2008-03-07. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- Silver Seek LLC. "Peak Copper Means Peak Silver - SilverSeek.com". News.silverseek.com. Archived from the original on 2013-11-04. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- COMMODITIES-Demand fears hit oil, metals prices Archived 2020-09-20 at the Wayback Machine, Jan 29, 2009.

- Will, Fritz G. (November 1996). "Impact of lithium abundance and cost on electric vehicle battery applications". Journal of Power Sources. 63 (1): 23–26. Bibcode:1996JPS....63...23W. doi:10.1016/S0378-7753(96)02437-8. INIST:2530187.

- "Department for Transport - Inside Government - GOV.UK". Dft.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2006-04-27. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- "APDA" (PDF). Apda.pt. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2006-10-06. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- "Phosphate Rock Statistics and Information" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-03-20. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-08-05. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Meena Palaniappan and Peter H. Gleick (2008). "The World's Water 2008-2009, Ch 1" (PDF). Pacific Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-20. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- "WorldŐs largest acquifer going dry". Uswaternews.com. Archived from the original on 2012-12-09. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- Archived July 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "How General is the Hubbert Curve?". Aspoitalia.net. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- "Laherrere: Multi-Hubbert Modeling". Hubbertpeak.com. Archived from the original on 2013-10-28. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- Dahl, Arthur Lyon (2012). "Achievements and gaps in indicators for sustainability". Ecological Indicators. 17: 14–19. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2011.04.032.

- Udo, Victor E.; Jansson, Peter Mark (2009). "Bridging the gaps for global sustainable development: A quantitative analysis". Journal of Environmental Management. 90 (12): 3700–3707. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.12.020. PMID 19500899.

- Allen S, Bennett M, Garcia C, Giovannucci D, Ingersoll C, Kraft K, Potts J, Rue C (2014-01-31). Everage L, Ingersoll C, Mullan J, Salinas L, Childs A (eds.). The COSA Measuring Sustainability Report (Report). Committee on Sustainability Assessment. Archived from the original on 2020-02-28. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- Keirstead, James; Leach, Matt (2008). "Bridging the gaps between theory and practice: A service niche approach to urban sustainability indicators". Sustainable Development. 16 (5): 329–340. doi:10.1002/sd.349.

- Fischer, Joern; Manning, Adrian D.; Steffen, Will; Rose, Deborah B.; Daniell, Katherine; Felton, Adam; Garnett, Stephen; Gilna, Ben; Heinsohn, Rob; Lindenmayer, David B.; MacDonald, Ben; Mills, Frank; Newell, Barry; Reid, Julian; Robin, Libby; Sherren, Kate; Wade, Alan (2007). "Mind the sustainability gap". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 22 (12): 621–624. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2007.08.016. PMID 17997188.

- Ekins, Paul; Simon, Sandrine (2001). "Estimating sustainability gaps: Methods and preliminary applications for the UK and the Netherlands" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 37: 5–22. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(00)00279-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-09-25. Retrieved 2019-07-09.